Lecture 15 of Book II James Joyce

advertisement

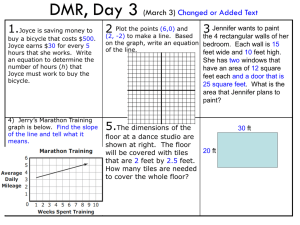

Lecture 15 James Joyce Modernism (1) The rise of modernist movement Modernism rose out of skepticism and disillusionment of capitalism, which made writers and artists search for new ways to express their understanding of the world and the human nature. The French symbolism was the forerunner of modernism. The First World War quickened the rising of all kinds of literary trends of modernism, which, toward the 1920s, converged into a mighty torrent of modernist movement. The major figures associated with the movement were Kafka, Picasso, Pound, Eliot, Joyce, and Virginia Woolf. Modernism was somewhat curbed in the 1930s. But after World War II, varieties of modernism, or postmodernism, rose again with the spur of Sarter's existentialism. However, they gradually disappeared or diverged into other kinds of literary trends in the 1960s. The characteristics of modernism Modernism amounts to more than a chronological description, that is to say, the more recent does not necessarily mean more modern. Modernism takes the irrational philosophy and the idea of psychoanalysis as its theoretical base. The major themes of the modernist literature are the distorted, alienated and ill relationships between man and nature, man and society, man and man, and man and himself. The chief characteristics of modernism are as follows: (A) Modernism marks a strong and conscious break with the past, by rejecting the moral, religious and cultural values of the past. (B) Modernism emphasizes on the need to move away from the public to the private, from the objective to the subjective. (C) Modernism upholds a new view of time by emphasizing the psychic time over the chronological one. It maintains that the past, the present and the future are one and exist at the same time in the consciousness of individual as a continuous flow rather than a series of separate moments. (D) Modernism is, in many respects, a reaction against realism. It rejects rationalism, which is the theoretical base of realism; it excludes from its major concern the external, objective, material world, which is the only creative source of realism; it casts away almost all the traditional elements in literature like story, plot, character, chronological narration, etc., which are essential to realism. As a result, the works created by the modernist writers can often be labeled as anti-novel, anti-poetry or anti-drama. Stream of consciousness Stream of consciousness is a phrase coined by W. James in his Principles of Psychology (1890) to describe the flow of thoughts of the human mind. Now it is widely used in a literary context to describe the narrative method whereby certain novelists describe the unspoken thoughts and feelings of their characters without resorting to objective description or conventional dialogue. Among English writers, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf are two major advocates of the technique. The ability to represent the flux of a character's thoughts, impressions, emotions, or reminiscences, often without logical sequence or syntax, marked a revolution in the form of novel. II. James Joyce: James ( Augustine Aloysius) Joyce (1882-1941) was an Irishman born into a Catholic family in Dublin and educated at Jesuit schools. He was a good student and was intended for a priest. But he renounced Catholicism at adolescence. He left Ireland and lived in France, Italy and Switzerland as "a voluntary exile", though his books were all written about Dublin because the Irish and Ireland were the people and the place he knew best and he believed that by writing about Dublin he was at the same time penetrating the heart of all cities and all mankind. Joyce suffered from an eye disease and lived all his life on the verge of poverty, but he was devoted to his work as a writer. His first important work was "Dubliners' (1914), a collection of 15 short stories, all realistic and impressionistic studies of the life, thoughts, dreams, aspirations and frustrations of diverse inhabitants in the Irish capital. He wrote: "My intention was to write a chapter of the moral history of my country and I chose Dublin for the scene because that city seemed to me the centre of paralysis (i.e. moral hemiplegia or spiritual poverty)." In this paralysed city, everything stands under the sway of priests. The young may dream of escaping from the narrow confines, but since even their dreams of getting away are shaped in the existing surroundings, their efforts often end in bitter resignation or fruitless discontent. In the story "Eveline", a Dublin girl, weary of her tedious life, has the chance to escape to Buenos Ayres with a sailor who wants to marry her. But this signifies a break with all her past life. At the last moment, she clings to the iron railing at the docks, incapable of following her suitor. These stories are written in accordance with Joyce's theory of ' epiphanies" .i.e. deep insights that might be gained through incidents and circumstances which seem outwardly insignificant. His first novel, "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man' (1916), is largely autobiographical. It describes the childhood, youth and early manhood of Stephen Dedalus, a highly gifted young Irishman. After mental torment and inner conflict, Stephen abandons Catholicism and leaves Ireland making up his mind to devote himself to artistic career in exile: 'I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it call itself my home. my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defence the only arms I allow myself to use-silence, exile, and cunning.' The plot is symbolic of the relation between an artist and society as well as that between art and exile in the modern western world. In the novel, there are changes of vocabulary, idiom, and prose structure to befit the various stages of the hero's development from childhood to early manhood, but the novel presents no difficulty as prose. It is the author's "preliminary canter over the field of infinite stylistic adaptability". “Ulysses" the novel which took Joyce 7 years to complete became a centre of controversy on its publication in 1922. In plot bearing a parallel to Homer's great epic ' Odyssey" which tells of the wanderings and adventures of 'the ancient Greek hero Odysseus, otherwise called Ulysses. Joyce's novel tells of the Wanderings and "adventures" of Leopold Bloom, a modern Ulysses, during the 24 hours of a single day, June 16. 1904. There are 3 main characters: Leopold Bloom, an ordinary Jewish businessman in Dublin, his wife Molly, a concert singer, and Stephen Dedalus from "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man", a writer like Joyce. The story is told through recording the characters' mental activities by the use of the" stream of consciousness" method. It shows how Leopold wanders about the Dublin streets on his daily business as an advertising agent, is tempted by the barmaids and lured by the shop--windows, meets Stephen m drunkenness and sends him home, but is all the time worrying about Molly, his .unfaithful wife, who is carrying on an affair with an impresario. Boylan--thus the reader may see "a whole individual" who is representative of universal human existence in modern western world. The "stream of consciousness" method was used by the author to depict what the inner, mental world of his characters actually was. Joyce was free in his experiments with the English language and grammar. Sometimes he retained the ordinary sentence structures, but more often he broke through "the fetters of syntax" In a chapter of the novel, the language goes through every stage in the development of English prose from Anglo-Saxon to the present day to symbolize the growth of a foetus in the womb. In the last chapter, Molly's natural, disconnected flow of thoughts in bed is recorded by the "stream of consciousness'' style of prose in 8 unpunctuated pages. "Finnegans Wake" (1939), Joyce's last novel, went even further in his experiments with his writing method. From the beginning to the end, it depicts a dream of Mr. Earwicker, a Dublin innkeeper", in a dream language". "In this immense work," a critic wrote. "Joyce had written a collection of words, some derived from languages other than English, and many apparently invented, whose significance no single reader can ever hope to gain." James Joyce was one of the most original novelists of the 20th century, whose work shows a unique synthesis of realism, the "stream of consciousness" and symbolism. His masterpiece "Ulysses" has been called "a modern prose epic". But he is also the greatest enigma in 20th-century literature. His admirers have praised him as "second only to Shakespeare in his mastery of the English language", whereas the average readers and not a few reviewers have complained that his masterpieces, especially "Finnegans Wake", are difficult to comprehend and even "unreadable". It may be still early to arrive at a final estimation of his literary achievement, we had better regard "Ulysses" and "Finnegans Wake" as unprecedented experiments in a new prose style and a new novel form, the verdict of whose real value will be given by future literary historians, or by Time, who is the most impartial literary historian of all. Artistic points of view (1) Joyce is a self-conscious and self-prepared artist. He holds that the subject matter of art should not be limited only to the sublime; anything that pleases the aesthetic sensitivity can be the subject matter of art. To Joyce, the creative artist should be concerned with the beautiful. As to how to apprehend the beautiful, Joyce quotes Aquinas' notion about the three required things for the perception of beauty, i.e. wholeness or integrity, harmony or proportion, and clarity or radiance. (2) Joyce believes that literary art can be roughly divided into three forms, i.e. lyrical, epical and dramatic. He also thinks that the artist is two in one: on one hand, he is an unconscious receptor, who reacts emotionally to the world around him; on the other hand, he is a conscious converter, and schemes them in different forms. (3) In Joyce's opinion, the dramatic form is the highest form of art. To his understanding, the artist, who wants to reach the highest stage and to gain the insights necessary for the creation of dramatic art, must rise to the position of god and be completely objective. (4) To Joyce, comedy is the perfect manner in art. That well explains why Joyce sticks to comedy in his writings. And this comic spirit, which makes its early appearance in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, achieves its great flowering in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. (1) Dubliners (1914) A collection of 15 short stories, it is the first important work of Joyce's lifelong preoccupation with Dublin life. The stories have an artistic unity given by Joyce who intended "to write a chapter of the moral history of my country.., under four of its aspects: childhood, adolescence, maturity and public life". Likewise, the stories progress from simple to complex. Each story presents an aspect of "dear dirty Dublin", an aspect of the city's paralysis--moral, political, or spiritual. Each story is an action, defining a frustration or defeat of the soul. And the whole sequence of the stories represents the entire course of moral deterioration in Dublin, ending in the death of the soul. (2) A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) (A) Story The story develops around the life of a middle-class Irish boy, Stephen Dedalus, from his infancy in the strongly Catholic, intensely nationalistic environment of Dublin in the 1880s to his departure from Ireland some twenty years later. In his childhood and adolescent period, Stephen experiences and feels the oppressive pressures from the moral, political and spiritual environment; with repeated frustrations and futile isolation, he turns to savage physical desire as an outlet. This, however, only makes matters worse and later at a moment of revelation on the seashore, Stephen suddenly realizes that the artistic vocation is his true mission and for its fulfillment he leaves Ireland. (B) Theme The title of this novel suggests a character study with strong autobiographical elements. So far as the subject matter is concerned, A Portrait belongs to the kind of fiction known as the Bildungsroman (Novel of Education). This kind of fiction is usually about a sensitive young man who is at first shaped by excessively powerful and oppressive forces of his environment but gradually realizes the pressure and rebels against it and tries to find his own identity. In this sense, Joyce's Portrait can be read as a straightforward, naturalistic account of the bitter youthful experiences and final artistic and spiritual liberation of the protagonist, Stephen Dedalus--Joyce's alter ego in the novel. (C) Structure The structure of A Portrait is based on the threedimension growth (i. e. physical, spiritual and artistic) of a sensitive boy to young manhood. In the novel, the author builds up a radiant pattern to expand Stephen's growth on different levels. By using subjective realism and the stream-of-consciousness technique, Joyce not only creates a natural pattern of Stephen's growing up: physically from infancy to manhood, intellectually from ignorance to scholarship, and in language from simple to complex, but also presents a convincing picture of Stephen's spiritual development from disillusion to overt rebellion and, symbolically, an exploration of the evolution of his artistic soul from the early fetal stage to the maturity and, finally, to the newly-born artist. To avoid slacken structure and make the novel more effective, Joyce adopts the device of montages to organize his novel. (3) Ulysses (1922) As Joyce's masterpiece, Ulysses has become a prime example of modernism in literature. It is such an uncommon novel that there arises the question whether it can be termed as a "novel" in the first place at all; for it seems to lack almost all the essential qualities of the novel in a traditional sense: there is virtually no story, no plot, almost no action, and little characterization in the usual sense. (A) Story Ulysses gives an account of man's life during one day, or exactly 18 hours, in Dublin. The three major characters are the Blooms, Leopaold Bloom, and his wife, Marion Tweedy Bloom (Molly), and Stephen Dedalus, the protagonist in A Portrait. The story of the novel is carried on more in the inner mind of the character than in the outside world. The events of the day, and what preoccupies the major characters of the novel alike, seem to be trivial, insignificant, or even banal. Beneath the surface of the events, nevertheless, the natural flow of mental reflections, the shifting moods and impulses in the characters' inner world are richly presented in an un-precedentedly frank and penetrating way. (B) Theme In Ulysses, Joyce seeks to present a microcosm of the whole human life by providing an instance of how a single event contains all the events of its kind, and how history is recapitulated in the happenings of one day. With great varieties and minute details, Ulysses embodies a symbolic picture of all human history, which is simultaneously tragic and comic, heroic and trivial, magnificent and dreary. Critics differ greatly so far as the novel's theme is concerned, some regard it as an encyclopedic satire on the degeneration and futility of modern life in Western world in which men become rootless, lonely, isolated from one another, alienated with the society, and frustrated by love. Actually, Ulysses is an anti-novel in which modern men are portrayed neither as heroes nor as villains, but as vulgar and trivial men with splitting personalities, disillusioned ideals, sordid minds and broken families, who are searching in vain for harmonious human relationships and spiritual sustenance in a decaying world. (C) Structure In Ulysses, Joyce is mainly concerned with his characters' psychic processes, which are formless. To compensate for this, Joyce makes use of several means to superimpose patterns or forms on his formless subject matter, such as the unities of time and place, Homeric and Biblical patterns, symbolic structures, image or word-phrase motifs, cyclical schemes, and so on. (D) Style Joyce takes great pains to create Ulysses from a complex of various techniques and experiments. But generally speaking, Joyce writes Ulysses in three main styles. The first is Joyce's original style: straightforward, lucid, logical and leisurely. Subtlety, economy and exactness are his standards. The second is a style mainly used to render the socalled stream of consciousness. The incomplete, rapid, broken wording and the fragmentary sentences are the typical features of this style, which reflect the shifting, flirting, disorderly flow of the thoughts in the major characters' mind. The third is a kind of mock-heroic style, the essence of which lies in the application of apparently inappropriate styles. Araby North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers' School set the boys free. An uninhabited house of two storeys stood at the blind end, detached from its neighbours in a square ground. The other houses of the street, conscious of decent lives within them, gazed at one another with brown imperturbable faces. The former tenant of our house, a priest, had died in the back drawing-room. Air, musty from having been long enclosed, hung in all the rooms, and the waste room behind the kitchen was littered with old useless papers. Among these I found a few paper-covered books, the pages of which were curled and damp: The Abbot, by Walter Scott, The Devout Communicant, and The Memoirs of Vidocq. I liked the last best because its leaves were yellow. The wild garden behind the house contained a central apple-tree and a few straggling bushes, under one of which I found the late tenant's rusty bicycle-pump. He had been a very charitable priest; in his will he had left all his money to institutions and the furniture of his house to his sister. When the short days of winter came, dusk fell before we had well eaten our dinners. When we met in the street the houses had grown sombre. The space of sky above us was the colour of ever-changing violet and towards it the lamps of the street lifted their feeble lanterns. The cold air stung us and we played till our bodies glowed. Our shouts echoed in the silent street. The career of our play brought us through the dark muddy lanes behind the houses, where we ran the gauntlet of the rough tribes from the cottages, to the back doors of the dark dripping gardens where odours arose from the ashpits, to the dark odorous stables where a coachman smoothed and combed the horse or shook music from the buckled harness. When we returned to the street, light from the kitchen windows had filled the areas. If my uncle was seen turning the corner, we hid in the shadow until we had seen him safely housed. Or if Mangan's sister came out on the doorstep to call her brother in to his tea, we watched her from our shadow peer up and down the street. We waited to see whether she would remain or go in and, if she remained, we left our shadow and walked up to Mangan's steps resignedly. She was waiting for us, her figure defined by the light from the half-opened door. Her brother always teased her before he obeyed, and I stood by the railings looking at her. Her dress swung as she moved her body, and the soft rope of her hair tossed from side to side. Every morning I lay on the floor in the front parlour watching her door. The blind was pulled down to within an inch of the sash so that I could not be seen. When she came out on the doorstep my heart leaped. I ran to the hall, seized my books and followed her. I kept her brown figure always in my eye and, when we came near the point at which our ways diverged, I quickened my pace and passed her. This happened morning after morning. I had never spoken to her, except for a few casual words, and yet her name was like a summons to all my foolish blood. . Her image accompanied me even in places the most hostile to romance. On Saturday evenings when my aunt went marketing I had to go to carry some of the parcels. We walked through the flaring streets, jostled by drunken men and bargaining women, amid the curses of labourers, the shrill litanies of shop-boys who stood on guard by the barrels of pigs' cheeks, the nasal chanting of streetsingers, who sang a come-all-you about O'Donovan Rossa, or a ballad about the troubles in our native land. These noises converged in a single sensation of life for me: I imagined that I bore my chalice safely through a throng of foes. Her name sprang to my lips at moments in strange prayers and praises which I myself did not understand. My eyes were often full of tears (I could not tell why) and at times a flood from my heart seemed to pour itself out into my bosom. I thought little of the future. I did not know whether I would ever speak to her or not or, if I spoke to her, how I could tell her of my confused adoration. But my body was like a harp and her words and gestures were like fingers running upon the wires. One evening I went into the back drawing-room in which the priest had died. It was a dark rainy evening and there was no sound in the house. Through one of the broken panes I heard the rain impinge upon the earth, the fine incessant needles of water playing in the sodden beds. Some distant lamp or lighted window gleamed below me. I was thankful that I could see so little. All my senses seemed to desire to veil themselves and, feeling that I was about to slip from them, I pressed the palms of my hands together until they trembled, murmuring: `O love! O love!' many times. At last she spoke to me. When she addressed the first words to me I was so confused that I did not know what to answer. She asked me was I going to Araby. I forgot whether I answered yes or no. It would be a splendid bazaar; she said she would love to go. `And why can't you?' I asked. While she spoke she turned a silver bracelet round and round her wrist. She could not go, she said, because there would be a retreat that week in her convent. Her brother and two other boys were fighting for their caps, and I was alone at the railings. She held one of the spikes, bowing her head towards me. The light from the lamp opposite our door caught the white curve of her neck, lit up her hair that rested there and, falling, lit up the hand upon the railing. It fell over one side of her dress and caught the white border of a petticoat, just visible as she stood at ease. `It's well for you,' she said. `If I go,' I said, `I will bring you something.' What innumerable follies laid waste my waking and sleeping thoughts after that evening! I wished to annihilate the tedious intervening days. I chafed against the work of school. At night in my bedroom and by day in the classroom her image came between me and the page I strove to read. The syllables of the word Araby were called to me through the silence in which my soul luxuriated and cast an Eastern enchantment over me. I asked for leave to go to the bazaar on Saturday night. My aunt was surprised, and hoped it was not some Freemason affair. I answered few questions in class. I watched my master's face pass from amiability to sternness; he hoped I was not beginning to idle. I could not call my wandering thoughts together. I had hardly any patience with the serious work of life which, now that it stood between me and my desire, seemed to me child's play, ugly monotonous child's play. On Saturday morning I reminded my uncle that I wished to go to the bazaar in the evening. He was fussing at the hallstand, looking for the hat-brush, and answered me curtly: `Yes, boy, I know.' As he was in the hall I could not go into the front parlour and lie at the window. I felt the house in bad humour and walked slowly towards the school. The air was pitilessly raw and already my heart misgave me. When I came home to dinner my uncle had not yet been home. Still it was early. I sat staring at the clock for some time and, when its ticking began to irritate me, I left the room. I mounted the staircase and gained the upper part of the house. The high, cold, empty, gloomy rooms liberated me and I went from room to room singing. From the front window I saw my companions playing below in the street. Their cries reached me weakened and indistinct and, leaning my forehead against the cool glass, I looked over at the dark house where she lived. I may have stood there for an hour, seeing nothing but the brown-clad figure cast by my imagination, touched discreetly by the lamplight at the curved neck, at the hand upon the railings and at the border below the dress. When I came downstairs again I found Mrs Mercer sitting at the fire. She was an old, garrulous woman, a pawnbroker's widow, who collected used stamps for some pious purpose. I had to endure the gossip of the tea-table. The meal was prolonged beyond an hour and still my uncle did not come. Mrs Mercer stood up to go: she was sorry she couldn't wait any longer, but it was after eight o'clock and she did not like to be out late, as the night air was bad for her. When she had gone I began to walk up and down the room, clenching my fists. My aunt said: `I'm afraid you may put off your bazaar for this night of Our Lord.' At nine o'clock I heard my uncle's latchkey in the hall door. I heard him talking to himself and heard the hallstand rocking when it had received the weight of his overcoat. I could interpret these signs. When he was midway through his dinner I asked him to give me the money to go to the bazaar. He had forgotten. `The people are in bed and after their first sleep now,' he said. I did not smile. My aunt said to him energetically: `Can't you give him the money and let him go? You've kept him late enough as it is.' My uncle said he was very sorry he had forgotten. He said he believed in the old saying: `All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.' He asked me where I was going and, when I told him a second time, he asked me did I know The Arab's Farewell to his Steed. When I left the kitchen he was about to recite the opening lines of the piece to my aunt. I held a florin tightly in my hand as I strode down Buckingham Street towards the station. The sight of the streets thronged with buyers and glaring with gas recalled to me the purpose of my journey. I took my seat in a third-class carriage of a deserted train. After an intolerable delay the train moved out of the station slowly. It crept onward among ruinous houses and over the twinkling river. At Westland Row Station a crowd of people pressed to the carriage doors; but the porters moved them back, saying that it was a special train for the bazaar. I remained alone in the bare carriage. In a few minutes the train drew up beside an improvised wooden platform. I passed out on to the road and saw by the lighted dial of a clock that it was ten minutes to ten. In front of me was a large building which displayed the magical name. I could not find any sixpenny entrance and, fearing that the bazaar would be closed, I passed in quickly through a turnstile, handing a shilling to a weary-looking man. I found myself in a big hall girded at half its height by a gallery. Nearly all the stalls were closed and the greater part of the hall was in darkness. I recognized a silence like that which pervades a church after a service. I walked into the centre of the bazaar timidly. A few people were gathered about the stalls which were still open. Before a curtain, over which the words Café Chantant were written in coloured lamps, two men were counting money on a salver. I listened to the fall of the coins. Remembering with difficulty why I had come, I went over to one of the stalls and examined porcelain vases and flowered tea-sets. At the door of the stall a young lady was talking and laughing with two young gentlemen. I remarked their English accents and listened vaguely to their conversation. `O, I never said such a thing!' `O, but you did!' `O, but I didn't!' `Didn't she say that?' `Yes. I heard her.' `O, there's a... fib!' Observing me, the young lady came over and asked me did I wish to buy anything. The tone of her voice was not encouraging; she seemed to have spoken to me out of a sense of duty. I looked humbly at the great jars that stood like eastern guards at either side of the dark entrance to the stall and murmured: `No, thank you.' The young lady changed the position of one of the vases and went back to the two young men. They began to talk of the same subject. Once or twice the young lady glanced at me over her shoulder. I lingered before her stall, though I knew my stay was useless, to make my interest in her wares seem the more real. Then I turned away slowly and walked down the middle of the bazaar. I allowed the two pennies to fall against the sixpence in my pocket. I heard a voice call from one end of the gallery that the light was out. The upper part of the hall was now completely dark. Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger. (1) Story A young boy, with the dawning awareness of sexuality, develops a strong liking toward the sister of one of his playmates. She asks him if he can go to a charity fair, for she cannot. He resolves to go and buy a gift for her. His uncle promises to give him the money he needs to go to the fair. But on the very day of the charity fair, his uncle comes home rather late. The waiting of his uncle's coming home torments him immensely. Nevertheless, he manages to get to the market only to be disappointed by the gap between his expectation and the actuality of the almost deserted fair. He perceives some insignificant events, overhears some minor conversations, and finally sees himself "as a creature driven and derided by vanity“. (2) Theme Insignificant as the events of the story may be, they constitute a meaningful episode of the protagonist's life experience that introduces him to awareness about the discrepancies between expectation and reality, between his pure infatuation about love and the reality of vulgarity. The story is carried on and organized by the quest on the boy's part of his idealized childish love, up to the point of the boy's recognition of the drabness and harshness of the adult world. The story is therefore basically about the loss of innocence—through painful experience the boy gets to know the complexities of a world that he once thought simple and predictable.