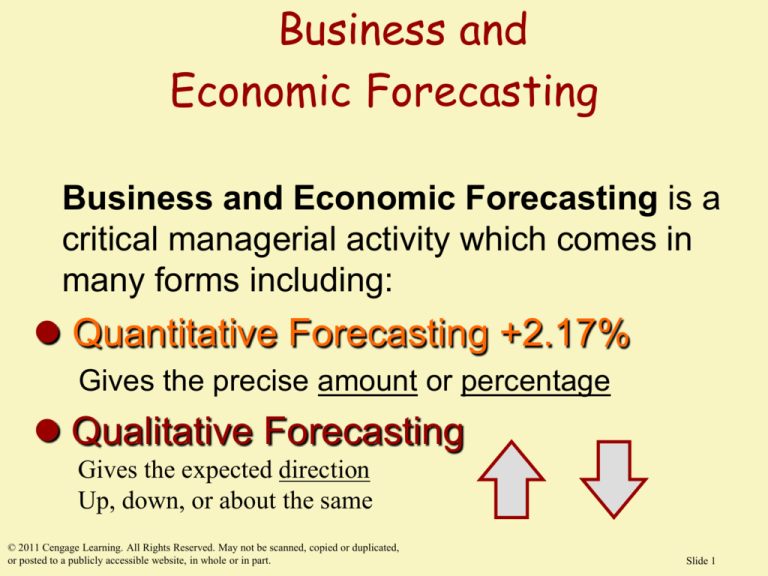

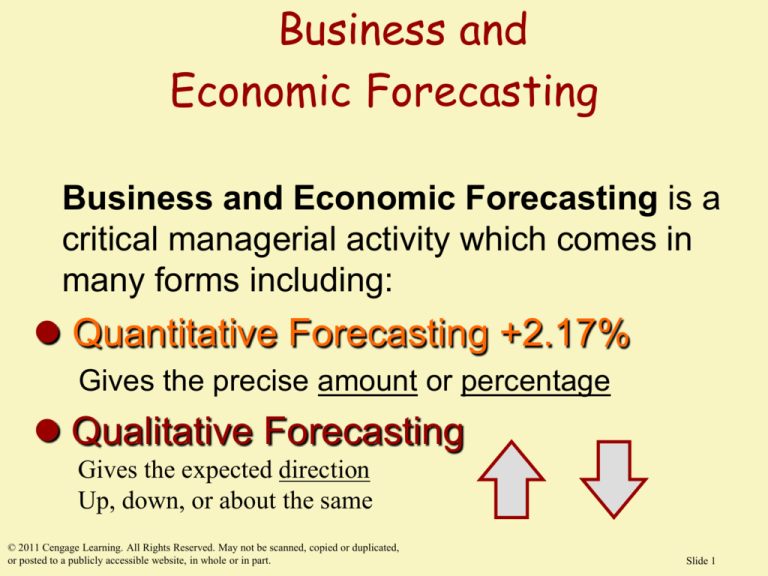

Business and

Economic Forecasting

Business and Economic Forecasting is a

critical managerial activity which comes in

many forms including:

Quantitative Forecasting +2.17%

Gives the precise amount or percentage

Qualitative Forecasting

Gives the expected direction

Up, down, or about the same

© 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated,

or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Slide 1

The Significance of Forecasting

• Both public and private enterprises operate under

conditions of uncertainty.

• Management wishes to limit this uncertainty by

predicting changes in cost, price, sales, and interest

rates.

• Accurate forecasting can help develop strategies to

promote profitable trends and to avoid unprofitable

ones.

• A forecast is a prediction concerning the future. Good

forecasting will reduce, but not eliminate, the

uncertainty that all managers feel.

Slide 2

Hierarchy of Forecasts

• The selection of forecasting techniques depends in part on the level of

economic aggregation involved.

• The hierarchy of forecasting is:

• National Economy (GDP, interest rates, inflation, etc.)

» Sectors of the economy (durable goods)

Industry forecasts (all automobile manufacturers)

Firm forecasts (Ford Motor Company)

o Product forecasts (The Ford Focus)

Slide 3

Criteria Used to Select a Technique

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

The choice of a particular forecasting method

depends on several criteria:

costs of the forecasting method compared with its

gains

complexity of the relationships among variables

time period involved

lead time between receiving information and the

decision to be made

accuracy of the forecast

Slide 4

Accuracy of Forecasting

• The accuracy of a forecasting model is measured by how

close the actual

variable, Y, ends up to the forecasting

variable, Y .

• Forecast error is the difference. (Y -Y)

• Models differ in accuracy, which is often based on the

square root of the average squared forecast error over a

series of N forecasts and actual figures

• Called a root mean square error, RMSE:

1

2

RMSE

(

Y

Y

)

t

t

n

Slide 5

ALTERNATIVE FORECASTING

TECHNIQUES

• Alternative forecasting techniques can be classified in the

following general categories:

»

»

»

»

»

»

»

Deterministic trend analysis

Smoothing techniques

Barometric indicators

Survey and opinion-polling techniques

Macroeconometric models

Stochastic time-series analysis

Forecasting with input-output tables

Slide 6

Deterministic Trend Analysis

• Time-series data. A series of observations taken

on an economic variable at various past points in

time.

»

»

»

»

Secular trends

Cyclical variations

Seasonal effects

Random fluctuations

• Cross-sectional data. Series of observations taken

on different observation units (for example,

households, states, or countries) at the same point

in time.

» Ratio to trend method

» Dummy variables

Slide 7

FIGURE 5.2 Secular, Cyclical, Seasonal, and

Random Fluctuations in Time Series Data

Slide 8

FIGURE 5.2 Secular, Cyclical, Seasonal, and

Random Fluctuations in Time Series Data

Slide 9

Elementary Time Series Models

for Economic Forecasting

^

Yt+1 = Yt

» The simplest method

» Best when there is no

trend, only random

error

» Graphs of sales over

time with and without

trends

» When trending down,

the simplest predicts

too high

NO Trend

time

Trend

time

Slide 10

Slide 11

Secular Trends

^ = Y + (Y - Y )

Y

t+1

t

t

t-1

» This equation begins with last period’s forecast, Yt, just

like the simple forecast.

» Plus an ‘adjustment’ for the change in the amount

between periods Yt and Yt-1.

» When the forecast is trending up or down, this

adjustment works better than the simple forecast

method #1.

Slide 12

Deterministic Trend Analysis

Components of Time Series

Dependent Variable

X

X

X

Forecasted Amounts

T0

TIME

The data may offer secular trends, cyclical variations, seasonal

variations, and random fluctuations.

Slide 13

Time Series

Examine Patterns in the Past

Dependent Variable

Secular Trend

X

X

X

Forecasted Amounts

T0

TIME

The data may offer secular trends, cyclical variations, seasonal

variations, and random fluctuations.

Slide 14

Time Series

Examine Patterns in the Past

Dependent Variable

Cyclical and Seasonal Variation

Secular Trend

X

X

X

Forecasted Amounts

T0

TIME

The data may offer secular trends, cyclical variations, seasonal

variations, and random fluctuations.

Slide 15

Linear Trend & Constant Rate of

Growth Trend

Linear Trend Growth

• Used when trend has a

constant AMOUNT of

change

Yt = a + b•T, where

Yt are the actual

observations and

T is a numerical time

variable

Uses a Semi-log Regression

• Used when trend is a

constant

PERCENTAGE rate

Log Yt = a + b•T,

where b is the

continuously

compounded growth

rate

Slide 16

FIGURE 5.4 Prizer Creamery: Monthly Ice Cream Sales

Slide 17

More on Constant Rate of Growth

Model – a proof

^

• Suppose: Yt = Y0( 1 + g) t where g is the

annual growth rate

• Take the natural log of both sides:

^

» Ln Yt = Ln Y0 + t • Ln (1 + g)

» but Ln ( 1 + g ) g, the continuously

compounded growth rate

» SO:

Ln Yt = Ln Y0 + t • g

Ln Yt = a + b • t

where b is the growth rate, g.

Slide 18

Numerical Examples:

MTB > Print c1-c3.

Sales Time Ln-sales

100.0

109.8

121.6

133.7

146.2

164.3

1

2

3

4

5

6

4.60517

4.69866

4.80074

4.89560

4.98498

5.10169

6 observations

Using this sales

data, estimate

sales in period 7

using a linear and

a semi-log

functional

form

Slide 19

The linear regression equation is

Sales = 85.0 + 12.7 Time

Predictor Coef

Constant

84.987

Time

12.6514

s = 2.596

Stdev

2.417

0.6207

R-sq = 99.0%

t-ratio p

35.16 0.000

20.38 0.000

R-sq(adj) = 98.8%

The semi-log regression equation is

Ln-sales = 4.50 + 0.0982 Time

Predictor Coef

Stdev

Constant 4.50416 0.00642

Time

0.098183 0.001649

s = 0.006899

R-sq = 99.9%

t-ratio

p

701.35 0.000

59.54 0.000

R-sq(adj) = 99.9%

Slide 20

Forecasted Sales @ Time = 7

• Linear Model

• Sales = 85.0 + 12.7 Time

• Sales = 85.0 + 12.7 ( 7)

• Sales = 173.9

• Semi-Log Model

• Ln-sales = 4.50 + 0.0982

Time

• Ln-sales = 4.50 +

0.0982 ( 7 )

• Ln-sales = 5.1874

• To anti-log:

linear

» e5.1874 = 179.0

Slide 21

Sales Time Ln-sales

Semi-log is

exponential

100.0

109.8

121.6

133.7

146.2

164.3

179.0

173.9

1

2

3

4

5

6

4.60517

4.69866

4.80074

4.89560

4.98498

5.10169

7 semi-log

7 linear

7

Which prediction

do you prefer?

Slide 22

Declining Rate of Growth Trend

• A number of marketing penetration models

use a slight modification of the constant rate

of growth model

• In this form, the inverse of time is used

Ln Yt = b1 – b2 ( 1/t )

• This form is good for patterns

like the one to the right

• It grows, but at continuously

a declining rate

Y

time

Slide 23

Seasonal Adjustments: The Ratio to Trend Method

12 quarters of data

1 2 3 41 2 3 41 2 3 4

Take ratios of the actual (A) to

the forecasted (F) values for

past years.

A1/F1, A2/F2, A3/F3, find

average of these ratios.

This is the seasonal adjustment

Adjust by this percentage by

multiply your forecast by the

seasonal adjustment

» If average ratio is 1.02,

adjust forecast upward 2%

Slide 24

Seasonal Adjustments: Dummy Variables

• Let D = 1, if 4th quarter and 0 otherwise

• Run a new regression:

Yt = a + b•T + c•D

» the “c” coefficient gives the amount of the adjustment for the

fourth quarter. It is an Intercept Shifter.

» With 4 quarters, there can be as many as three dummy variables;

with 12 months, there can be as many as 11 dummy variables

• EXAMPLE: Sales = 300 + 10•T + 18•D

12 Observations from the first quarter of 2008-I to 2010-IV.

Forecast all of 2011.

Sales(2011-I) = 430; Sales(2011-II) = 440; Sales(2011-III) = 450;

Sales(2011-IV) = 478

Slide 25

Smoothing Techniques: Moving Averages

• A smoothing forecast

method for data that

Dependent Variable

jumps around

• Best when there is no

*

*

trend

*

• 3-Period Moving Ave is:

*

^

Yt+1 = [Yt + Yt-1 + Yt-2]/3

• For more periods, add

them up and take the

average

*

Forecast

Line is

Smoother

TIME

Slide 26

FIGURE 5.6 Walker Corporation’s ThreeMonth Moving Average Sales Forecast Chart

Slide 27

Smoothing Techniques

First-Order Exponential Smoothing

• A hybrid of the Naive • Each forecast is a function of

and Moving Average

all past observations

methods

• Can show that forecast is

^

^ t+1 = w•Yt +(1-w)Yt

• Y

based on geometrically

declining weights.

• A weighted average of

^ = w •Y +(1-w)•w•Y +

past actual and past

Y

t+1

t

t-1

forecast, with a weight (1-w)2•w•Yt-2 + …

of w

Find lowest RMSE to pick the

best w.

Slide 28

First-Order Exponential

Smoothing Example for w = .50

1

2

3

4

5

Actual Sales

100

120

115

130

Forecast

100 initial seed required

.5(100) + .5(100) = 100

?

Slide 29

First-Order Exponential

Smoothing Example for w = .50

1

2

3

4

5

Actual Sales

100

120

115

130

Forecast

100 initial seed required

.5(100) + .5(100) = 100

.5(120) + .5(100) = 110

?

Slide 30

First-Order Exponential

Smoothing Example for w = .50

1

2

3

4

5

Actual Sales

100

120

115

130

?

Forecast

100 initial seed required

.5(100) + .5(100) = 100

.5(120) + .5(100) = 110

.5(115) + .5(110) = 112.50

.5(130) + .5(112.50) = 121.25

MSE = {(120-100)2 + (110-115)2 + (130-112.5)2}/3 = 243.75

RMSE = 243.75 = 15.61

Period 5

Forecast

Slide 31

Barometric Techniques

Slide 32

Barometric Techniques

Slide 33

Barometric Techniques

Direction of sales can be indicated by other variables.

PEAK

Motor Control Sales

peak

Index of Capital Goods

TIME

4 Months

Example: Index of Capital Goods is a “leading indicator”

There are also lagging indicators and coincident indicators

Slide 34

Average time given in months from reference peaks

Table 5.7

LEADING INDICATORS*

»

»

»

»

COINCIDENT

INDICATORS

M2 money supply (-14.2)

S&P 500 stock prices (-11.1)

» Nonagricultural payrolls

Building permits (-15.4)

(+.8)

Initial unemployment claims

» Index of industrial

(-12.9)

production (-1.1)

Contracts and orders for

» Personal income less

plant and equipment (-7.3)

transfer payment (-.4)

LAGGING INDICATORS

»

*http://www.nber.org

» Inventory to sales ratio (9.2)

» Prime rate (+2.0)

» Change in labor cost per unit

of output (+6.4)

Slide 35

Surveys and Opinion Polling Techniques

• New product ideas have no historical data, but surveys can

assess interest ( Would you buy a phone that is also a Swiss knife? )

• Macroeconomic surveys include:

» Plant and equipment expenditure plans (McGraw-Hill, National

Industrial Conference Board, US Department of Commerce, Fortune).

» Plans for inventory changes and sales expectations (US Department

of Commerce, McGraw-Hill, Dun and Bradstreet, and the National

Association of Purchasing Agents)

» Consumer expenditure plans (U of Michigan’s Survey Research

Center on plans to buy autos, called consumer sentiment)

• Sales Forecasting include:

» Sales force polling (sales people know what their customers are

saying)

» Surveys of consumer intentions (asking prior customer’s their

intentions for replacing appliances, windows, etc.)

Slide 36

Econometric Models

Single Equation Models

• Specify the variables in the model. One example is

attendance at NFL games involving 14 variables from

price, weather, domes, non-Sunday games, and winning

record at home.

• Estimate the parameters of a typical demand function:

» Qd = a + b•P + c•I + d•Ps + e•Pc

• But forecasts require estimates for future prices, future

income, etc.

• Often combine econometric models with time series estimates of the

independent variable.

Slide 37

Example:

Suppose demand estimate to be:

• Qd = 400 - .5•P + 2•Y + .2•Ps

» anticipate pricing the good at P = $20

» Income (Y) is growing over time, the estimate is: Ln

Yt = 2.4 + .03•T, and next period is T = 17.

• Y = e2.910 = 18.357

» The prices of substitutes are likely to be P = $18.

• Find Qd by substituting in predictions for P, Y, and Ps

• Hence Qd = 430.31

Slide 38

Econometric Models

Multi-Equation Models

• In market (and life) interrelationships may be complex.

• Macroeconomic models of national income often involve

several equations for consumption, GDP, investment and

government.

i. C = a1 + b1 (GDP – T) + e1

ii. I = a2 + b2Pt-1 + e2

iii. T = b3GDP + e3

iv. GDP = C + I + G

• Such models offer forecasts, but can be supplemented

with judgment of the forecasters.

Slide 39

Slide 40

Slide 41

Stochastic Time Series

• A little more advanced methods incorporate into time

series the fact that economic data tends to drift

yt = a + byt-1 + et

• In this series, if a is zero and b is 1, this is essentially

the naïve model. When a is zero, the pattern is called a

random walk.

• When a is positive, the data drift. The Durbin-Watson

statistic will generally show the presence of

autocorrelation, or AR(1), integrated of order one.

• One solution to variables that drift, is to use first

differences.

Slide 42

Random Walks Illustrated

Slide 43

Cointegrated Time Series

• Some econometric work includes several stochastic

variable, each which exhibits random walk with drift

» Suppose price data (P) has positive drift (trends up)

» Suppose GDP data (Y) has positive drift (trends up too)

» Suppose the sales is a function of P & Y

» Salest = a + bPt + cYt

» It is likely that P and Y are cointegrated in that they

exhibit co-movement with one another. They are not

independent.

» The simplest solution is to change the form into first

differences as in: DSalest = a + bDPt + cDYt

Slide 44

Managing in the

Global Economy

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Import-Export Sales and Exchange Rates

The Market for US Dollars as Foreign Exchange

Foreign Exchange (FX) Risk Management

Determinants of the Long-Run Trends in Exchange Rates

Purchasing Power Parity

International Trade and Trading Blocs (EU & NAFTA)

Comparative Advantage and Trade

Trade Deficits and the Balance of Payments

© 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated,

or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Slide 45

The Financial Crisis

and Exports to China

• The financial crisis in housing and banking led to a prolonged

recession

• US is largest at $14+ trillion; Japan at $5 trillion; China at $4.4

trillion; Germany at $3.7 trillion; and France at $2.8 trillion.

• Though a relatively small portion of US GDP (of 10% exports &

13% imports), exports and imports have been a driver of growth.

• Although both consumers and businesses cut back in

expenditures, exports to China continued.

• Solutions to global downturn involves expansionary fiscal and

expansionary monetary policies, although neither has been

especially successful thus far.

Slide 46

The Financial Crisis

and Exports to China

Slide 47

Import-Export Sales and Exchange Rates

• More and more firm are becoming

multinational enterprises.

• Exports and imports are influenced by

changes in international exchange rates.

• Differences in long run inflation rates

(according to the theory of purchasing power

parity), national economic growth rates, and

interest rates help explain long-term

exchange rate movements.

Slide 48

FIGURE 6.1 Foreign Exchange (FX) Rates: The Value of

the U.S. Dollar against Several Major Currencies

Slide 49

Competitiveness and Exchange Rates

• The international competitiveness of

products is affected by exchange rates.

• If the US exports a Jeep that sells for $30,000, the price of the same

car in Europe is vastly different

» In 2000, $/€ = $.86/€. If a US car costs $30,000, then in Euros

that is $30,000 / $.860/€ or €34,884.

When $/€ = $.86/€, then €/$ = 1/ $.86/€ = €1.163/$

» In 2010, $/€ = $1.32/€. If that same car costs $30,000, then in

Euros that is $30,000 / $1.32/€ or €22,727.

When $/€ = $1.32/€, then €/$ = 1/ $1.32/€ = €.757/$

» Clearly, more Jeeps are likely to be sold in Europe at the lower

than the higher price.

Slide 50

Foreign Exchange Risk Exposure

• Transaction Risk Exposure – occurs when a change in cash flows

results from contractual commitments to pay or receive a foreign

currency.

» When GE sells equipment to Japan in Yen, but they give 60 days before the

payment is due, there is a risk that the Yen will fall in value.

• Translation Risk Exposure – occurs when the value of foreign

assets or liabilities are affected by exchange rates.

» Disney owns a park near Paris. When the Euro rises against the dollar, the

value of the land rises in terms of dollars. This is primarily an accounting

adjustment.

• Operating Risk Exposure – occurs when cash flows of the firm are

impacted by exchange rates.

» When Jeep sells more Grand Cherokees when the value of the dollar is low,

and less when it is high, this is operating risk exposure. This is the most

important risk.

Slide 51

The Market for US Dollars as

Foreign Exchange

• Jeep, BMW, and Cummins Engine are buying

and selling foreign exchange in the market.

• Governments can also intervene through

buying or selling currencies that they hold.

• Spot Price for foreign exchange is current

price(2 day delivery) can appear in different

terms: $/€ or €/$, which is just the inverse.

Both are given in the Cross Rates.

• Forward Price is the price of a foreign

currency for delivery at a future date agreed by

contract today

Slide 52

FIGURE 6.2 Cummins Engine Cash

Flow and Operating Margins

Slide 53

Canadian Dollar

Spot and Forward Rates

August 6, 2010

http://fx.sauder.ubc.ca/CAD/forward.html

Country

Canada (C$) spot

1-month forward

3-months forward

6-months forward

US$ per 1C$

0.9730

0.9727

0.9715

0.9694

What does the market think will happen to the C$

based on the forward rates over the long run?

Slide 54

CROSS RATES 8-6-10

USD $

JPY ¥

EUR €

CAD $

GBP £

AUD $

CHF

1 USD $

–

85.435

0.7526

1.0273

0.6264

1.0891

1.0386

1 JPY ¥

0.0117

–

0.0088

0.012

0.0073

0.0127

0.0122

1 EUR €

1.3287 113.5198

–

1.365

0.8323

1.4471

1.38

1 CAD $

0.9734

0.7326

–

0.6098

1.0602

1.011

1 GBP £

1.5964 136.3905 1.2015

1.64

–

1.7387

1.658

1 AUD $

0.9182

78.4455

0.691

0.9433

0.5752

–

0.9536

1 CHF

0.9628

82.2598

0.7246

0.9891

0.6031

1.0486

–

83.1646

http://finance.yahoo.com/currency-investing#cross-rates

USD $ is the US dollar; JPY ¥ is the Japanese yen; EUR € is the European Euro; GBP is the

Slide 55

British pound; AUD $ is the Australian dollar; and CHF is the Swiss franc

Outsourcing

• Global firms seek lowest cost ways to produce

• When firms do one or more steps of their production

outside of their home country, we say that activity was

“outsourced”

• This can help firms survive that face stiff competition

from abroad by holding down their costs. In this

way, some jobs are saved while others leave this

country.

• Outsourcing is criticized as ‘exporting jobs.’

Slide 56

FIGURE 6.3 Outsourcing Shipping Costs and Component

Sources for HP Personal Computer

Slide 57

China Trade Blossoms

• Worldwide trade with China jumped from 4.2%

in 2003 to 8% in 2008, and is growing.

• China as joint ventures with global firms (Ford,

McDonnell-Douglas, HP, and many others).

• GDP in China grows at phenomenal rates

doubling in 5-7 years, and population growing at

1%, improving their standard of living.

• Liberalization of property rights and the creation

of a middle class are hallmark’s of moving from

a developing to a developed country.

Slide 58

The Market for Dollars

as Foreign Exchange

• Foreign Exchange is used

for trade and investment.

Use a supply & demand

model to explore FX

rates

• Demand for Swiss Francs

(SFr): Demand is associated

with US demand for imports

from Switzerland and

purchase of Swiss financial

securities

$/SFr

1,000 SFr

D

SFr

Slide 59

Supply of SFr

• Supply of SFr -Supply is associated

with SWISS demand

for US exports and US

financial investments.

• Market Clears-$/SFr

no excess demand or

excess supply of SF

• In Flexible Markets, buying

& selling through

international banks

S

$.9628

D

SFr

Slide 60

Suppose there is a rise in

US Inflation Rates

S'

• Both Supply & Demand of

SFr Shift

S

• SWISS products appear

cheaper, so D shifts to D′ $2/SFr

• US exports appear

more expensive, so

shifts from S to S′

$1/SFr

D'

• The SFr appreciates, and

the dollar depreciates

D

SFr

Slide 61

Suppose U.S. interest rates rise

• Supply of Swiss francs rises

as Swiss seek to invest in

the US from S to S′

• Demand for Swiss

investments declines, from

$1/SFr

D to D′

• Swiss francs fall in value and

the dollar rises in value

$2/SFr

• What happens when

Greenspan CUTS interest

rates?

S

S′

D

D'

Slide 62

Suppose US Economic Growth rises

• Supply of Swiss francs rises

as Swiss seek to invest in

the US from S to S′

• Demand for Swiss products

and services rise from D to

$1/SFr

D′ as growth increases

$2/SFr

appetite for everything.

• Swiss francs fall in value and

the dollar rises in value

• What happens when Swiss

growth rates rise?

S

S′

D'

D

Slide 63

FIGURE 6.4 The Market for U.S. Dollars as

Foreign Exchange (Depreciation of the Dollar,

2001–2008)

Slide 64

Governmental Intervention in Foreign

Exchange Markets

• Governments can and do intervene in markets

» Directly by buying and selling foreign currencies

» And indirectly by altering interest rates or inflation rates

• Sterilized Interventions involve offsetting an

indirect move (like an increase in short term

interest rates) through direct action in the

foreign currency markets

• Coordinated Interventions involve several

countries all agreeing to intervene to raise or

lower the exchange rate of some country.

Slide 65

Determinants of Long-Run Trends

in Exchange Rates

1. Countries that have high growth rates in

GDP tend to have rising currency values.

2. Countries that have relatively high real

(inflation-adjusted) interest rates, tend to

have rising currency values .

3. Countries with relatively high inflation

expectations tend to declining currency

values.

Slide 66

Slide 67

FIGURE 6.5 The Market for U.S. Dollars as

Foreign Exchange (Depreciation against the Yen,

2007–2009, and the Euro, 2001–2008)

Slide 68

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

• Purchasing power parity says that the price of

traded goods tends to be equal around the world.

This is: the law of one price.

» if exchange rates are flexible and there are no

significant costs or barriers to trade, then:

Relative PPP [6.1]:

S1 = ( 1 + h )

S0 ( 1 + f )

S1/S0 shows the expected change in the direct quote of a

currency. The right side of the equation is the ratio of home and

foreign inflation rates. If the foreign inflation rises (f), then the

domestic expected future spot rates S1 declines.

Slide 69

Slide 70

PPP Example

• Suppose inflation in the US is 3%

• Suppose that inflation in Canada is 4%

• The currency price of the Canadian dollar is

$.973/C$.

• What is the expected price of the Canadian dollar

in one year?

• Answer:

S1 = ( 1 + h ) = 1.03 = .9903 = S1

S0 ( 1 + f ) 1.04

.973

• Hence, S1 = .973*.9903 = $ 0.9636/C$, a slight

decline from $.973.

Slide 71

PPP As Yardstick Of Comparative Growth

• PPP can be used to compare growth rates

• An “implied FX” rate is the ratio of prices of like items

in two countries, say iPods sold in US and UK.

» A $225 iPod in US and the same one in the UK for £167, for

an implied exchange rate of $1.347/£ = $225/£167.

» The law of one price says identical items priced the same

» PriceUS = PriceUK x Implied FX

» $225 = £167 x ($1.347/£), which says iPods in both countries

cost the same.

• Even though Chinese currency (Yuan) is managed, we

can uncover an implied exchange rate using PPP. It is

more like 3.8Yuan/$ than the official rate of 6.8Yuan/$.

Slide 72

Qualifications of PPP

1. PPP is sensitive to the starting point, S0. The base time

period may not in equilibrium.

2. Differences in the traded goods, or cross-cultural

differences, may prevent the law of one price to

equilibrate price differences.

»

If a product like Italian “Dixan” is unknown in the US to

wash dishes, it is not viewed a substitute for Joy or Dawn

dishwashing liquid.

3. The inflation rate used may include some non-traded

goods.

4. PPP tends to work better in the long run than in short

run changes in inflationary expectations.

Slide 73

Big Mac Index

• Although prepared food is not a traded good, we

can investigate what is the dollar price of

McDonald’s Big Mac is in various countries.

• In the US, the Big Mac sells for $2.99

• In Japan, the Big Mac sells for ¥600, but a dollar

buy ¥90. So, in dollar terms, the Big Mac sells for

¥600/(¥90/$) = $6.67

» They are not equal. It shows that a Big Mac does cost

more in Japan.

» However, we tend to find that products become

somewhat more equivalent in cost over time.

Slide 74

Trade-Weighted Exchange Rate Index

• With many countries and many exchange rates, whether a

currency rose or fell is complex. We tend to combine the cost of

foreign currency into an index based on the amount of trade to

each country.

• The trade-weighted exchange rate index is a measure of the

value of the dollar.

• The index, EER, is weighted by the amount of trade with other

countries, wit. An index of the change in value of pairs of

currencies since a base year, eI$it.

• If £.40/$ is the exchange rate in the base year and is now £.50/$,

then the index is (£.50/$) /(£.40/$) · 100 = 125.

• This means that the dollar is 25% more expensive to the British.

The index is:

$

$

t

it

it

t

EER eI w

Slide 75

Slide 76

International Trade

and Regional Trading Blocs

• US trade has been growing over the past 25 years, and

a growing proportion of all world trade now

comprising 31% of world trade (exports + imports).

• Exports have contributed to US GDP growth.

• Part of the growth is within regional trading blocs

» NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement

expanded trade among US, Canada, and Mexico.

» EU, the European Union, and the creation of the Euro

expanded trade within Europe

» MERCOSUR, expanded trade among Argentina, Brazil,

Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia, and Chile

» Less dramatic, but similar patterns in ASEAN (Association

of Southeast Asian Nations) and APEC (Asian-Pacific

Economic Cooperation).

Slide 77

Slide 78

Slide 79

Slide 80

Slide 81

Real Terms of Trade

Example: Table 6.3

Real Terms of Trade involves a comparison of costs across

Countries.

Absolute Cost US

Absolute Cost Japan

Carburetors

$120

¥10,000

Memory Chips

$300

¥ 8,000

The question is: Which country should make

carburetors and which should make chips?

Slide 82

Comparative Advantage

• Countries or firms should produce more of those goods for which

they have lower relative cost.

Relative Cost in US Relative Cost in Japan

Carburetors .4 Chips = $120/$300

1.25 Chips =

10,000/8,000

Computer

Chips

2.5 Carb.= $300/$120

8 Carb. =

8,000/10,000

• It costs $120 in the US to make a carburetor and $300 to make chips, the

“cost” of a carburetor is the .4 chips foregone (take the ratio $120/$300 to find

.4 chips).

• The US relative cost of carburetors is much lower than that of the Japanese

(1.25 Chips), whereas the Japanese relative cost of chips (.8 Carburetors) is

much lower than that of the US.

• Japan should make chips and US should make carburetors and the US

should make carburetors. Both are cheapest!

Slide 83

Slide 84

Gains from Comparative Advantage

• In this example, suppose that both countries currently make 1

carburetor and 1 chip.

• World production is 2 carburetors and 2 memory chips before

trade.

• Now, let the US make all of the carburetors. Since each chip

given up is 2.5 carburetors, the US now makes 3.5 carburetors

(the one they were making and the 2.5 extra ones made).

• Let Japan also specialize in memory chips. They stop making

the carburetor and make instead 1.25 chips. Along with the

original chip, they make 2.25 chips.

• World production rose to 3.5 carburetors and 2.25 chips through

comparative advantage.

• Both countries will be richer by this trade.

Slide 85

Import Controls and Protective Tariffs

• Tariffs – taxes on foreign-produced goods designed to

raise revenues and assist local over foreign producers.

» Expands domestic production

» But raises the price for consumers

» May lead to foreign retaliation imposing tariffs on your own

exports

• Import quotas – limits on goods imported

» Sometimes voluntary quotas, as when Japan restricted the number

of cars exported to the US.

» This also raises the price for consumers

• Exchange rate controls – limits on FX permitted

» Reduces trade by restricting access to foreign currencies

Slide 86

FIGURE 6.12 Trade-Weighted

Tariffs, 2008

Slide 87

The Case For and Against a Strategic Trade Policy

I. The case for helping

particular industries:

II. The case against helping

particular industries:

1. Help industries related

to national defense

2. Help infant industries

3. Offset subsidies given

by foreign competitors

4. Anti-dumping

sanctions

5. Increasing returns

6. Network externalities

1. National income is typically

reduced by trade restrictions

2. Violation of the WTO, the

World Trade Organization

3. Every industry thinks it needs

special help

4. Free Trade avoids trade wars

5. Unclear if governments knows

which industry is likely to be

desirable in the future.

Slide 88

Optimal Currency Areas

• The Optimal Currency Area involves the question of how

many different currencies are best.

» If all of Europe has only one currency, trade is quite easy.

• But when Greece needed assistance, reducing the value of

the Euro for the whole group of countries doesn't target

the single ailing region.

» It is expected that the Euro helps the participating countries, but

it makes helping the poorest countries harder.

• Labor mobility is still restricted in Europe.

• Although each country has its language and culture, they

all have been subject to correlated shocks: higher oil

prices, trade collapse, leading to a growing dispersion of

unemployment rates.

Slide 89

What about One Currency

for NATFA?

• Should the US, Canada, and Mexico consider having

one united currency, the Peso-Dollar?

• The US has the same currency in all 50 states, and this

has helped the US. All states have open borders, so

Ohio workers can move to Missouri if they want to find

work.

» But one currency makes helping poorer states harder.

» If problems arise in Mexico, they would not

be able to depreciate the peso to help.

» Also, open borders within North America does

not exactly exist.

$

Slide 90

Slide 91

Slide 92

What is US’ Largest Trading Partner?

• Canada is the US’s largest trading partner, due in part to its

location and NAFTA

• Prior to NAFTA, the region called maquiladora in Northern

Mexico permitted US firms to assemble US parts and ship

finished goods back to the US without tariff. Now, all of

Mexico is essentially maquiladora through NAFTA.

• Trade restrictions are side-stepped by:

» Parallel imports – arbitrage of tariffs across countries (the

low tariff buyers sell to higher tariff buyers)

» Gray markets and Knockoffs – selling possibly counterfeit

versions of branded goods

Slide 93

Slide 94

The Persistent US Trade Deficit

• The US has often had a trade deficit

• A trade deficit must be offset by capital

inflows (foreigners buying US securities,

bonds, or other lending)

• What are reasons for a large trade deficit?

» Outsourcing of production outside the US

» Oil imports

» Exchange rates that make foreign goods look

cheap (as with an under-priced Chinese Yuan)

» And the willingness of other nations to use the

dollar as a form of safe-haven.

Slide 95

Slide 96