Disproportionate Representation of Minority Students in Programs

advertisement

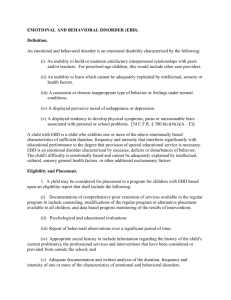

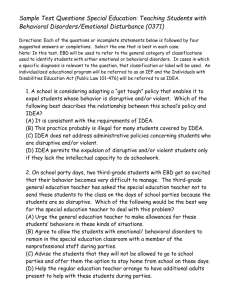

Disproportionate Representation of Minority Students in Programs for Students with Behavioral Disorders Ohio CCBD June 26, 2009 Gwendolyn Cartledge, Ph.D. The Ohio State University cartledge.1@osu.edu Lenwood Gibson Gibson.476@osu.edu Starr Keyes Keyes.20@osu.edu Presentation Outline Disproportionality for Culturally Diverse Learners (CLD) Cultural Competence in Perceptions Cultural Competence in Behavioral Interventions Cultural Competence in Academic Interventions Disproportionate Minority Representation in Special Education Minority students are disproportionately overrepresented in special education African American children are identified at 1.5 to 4 times the rate of white children in the disability categories of LD, MR, and EBD. They make up 14.8% of pupil population but 26.4% of students in EBD (Drakeford, Cramer, & Staples, 2006; Losen & Orfield, 2002) There is disproportionality in the representation of Native and Hispanic Americans in some areas as well Asian American children are under identified in these areas, raising the question of whether the special education needs of these children are being met Prevalence of EBD in CLD groups EBD more prevalent in African-American youth from low-SES households and families without two parents (Achilles, McLaughlin, & Croninger; 2007) Rates of EBD by gender Girls underidentified for EBD. Possible factors: internalizing might not be detected by existing measurement/identification tools gender role assumptions (Rice, Merves, & Srsic; 2008) Sample population in Quality of Life study: Out of 86 students, only 19 female (Sacks & Kern; 2008) Ohio rates by gender Males overwhelmingly identified with EBD as opposed to females ODE Power Report 2007-2008 enrollment by student demographic: Males comprised 80% of students enrolled w/EBD Ohio EBD prevalence by group 2007-2008 School Year Percent of School Population Males Females Percent of EBD Population Males Females Asian or Pacific Islander .7 .8 .2 .2 Black, NonHispanic 8.3 8.1 25 7 1.3 1.3 1.6 .3 .05 .05 .1 NC 1.7 1.7 3.6 .9 39 37 49 12 Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native Multiracial White, NonHispanic Discipline and exclusion Highest disciplinary rates for students w/EBD EBD & ADHD more likely than LD to be excluded; African-American & Hispanics more likely than Whites to be excluded; Male and older students more likely be excluded (Achilles et al., 2007) More severe disciplinary procedures used for students with EBD (Bradley, Doolittle, & Bartolotta; 2008) Setting Students with EBD participate in general education curriculum less: are more likely to be serviced with other students with EBD; are excluded from instructional settings more than any other disability category (Bradley et al., 2008) More segregated settings for AA, Hispanic, Native Am, & ELL students as opposed to White, Asian/PI, other, and non-ELL students (De Valenzuela, Copeland, Qi, & Park, 2006) Outcomes for Students with EBD Poor school and post-school outcomes for students with EBD; with negligible change over time (Bradley et al., 2008; Kern, Hilt-Panahon, & Sokol; 2009) More likely to receive lower grades and have the lowest high school completion rate (e.g., drop out at twice the rate of general education students) Difficulty with employment, postsecondary education, personal relationships, and high rate of involvement in justice system (Bradley et al., 2008) Outcomes (cont’d) Consistently highest dropout rates for students with EBD and LD Lower odds of dropping out if: never have been retained; prepared for class; completed homework; tardy less often Greater odds of dropping out if: misbehave more; cut class; absent (Reschly & Christenson, 2006) Data from One Elementary School: Disciplinary Data Summary Nearly 50% of school population had disciplinary referrals. Number of referrals increased dramatically in the spring of each school year. Males received more referrals than females: 60% year 1, 73% year 2. African American males: % in population % referrals Year 1 41.6% 53.1% Year 2 38.5% 64.3% Data from One Elementary School: Frequent Repeaters 15 or more referrals (16 students) 5-14 referralsm (16 students) 1-4 referrals (9 students) 80 Number of office referrals 70 60 Year 1 50 40 30 20 10 0 Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May 00 00 00 00 01 01 01 01 01 01 01 01 01 02 02 02 02 02 Month Culturally competent teachers are able to face themselves - are introspective (Howard 2003) When dealing with disciplinary actions, for example, teachers need to ask: • Are disciplinary actions disproportionate to one subgroup? • What messages are being sent to student members of that group and to nonmembers? • Are students punished for teachers’ lack of skill in behavior management? • Are students punished for culturally specific behaviors? School orientation begins to dwindle at about the 4th grade. Boys begin to seek other means to affirm themselves, perhaps due more to hostile school climate than to peer pressure against “acting white.” When removal from classroom life begins at an early age, it is even more devastating, as human possibilities are stunted at a crucial formative period of life. Each year the gap in skills grows wider and more handicapping, while the overall process of disidentification … encourages those who have problems to leave school rather than resolve them in an educational setting (Ferguson, p. 230). Cultural Competence Ways in which schools aggravate social adjustment problems of culturally diverse learners: Monocultural curriculum (fail to recognize background of culturally diverse learner) Individualistic/competitive environments Disproportionate disciplinary referrals with harsher penalties More restrictive educational placements Low expectations Cultural Competence Clash between culture of school (control/authority) & males (need to be empowered/affirmed) cultural discontinuities Need for greater cultural competence by school personnel Reduce hostile school climate through culture of caring Develop positive student - teacher relationships Provide direct and intense instruction in desired social and academic skills Cultural Competence Empower and affirm males through: Social skill instruction in needed behaviors Individualized behavior plans Effective/intensive academic instruction Social Skills Instruction Motivation and Rationale Skill Components/Steps Modeling Guided Rehearsal and Practice Independent Practice Skill Review and Reinforcement Maintenance and Generalization “Responding to Conflicts and Aggression” Instruction Using folktale to teach social skills (Cartledge & Kleefeld, 1994; in press) A Lot of Silence Makes a Great Noise Skill Components When someone says or does something to bother or threaten us, we: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Don’t look at the person. Don’t talk to the person. Think about how to get away. If you can, get away. Go to a safe place. If necessary, call for help. Modeling, Guided, and Independent Practice Situation: You are walking home from school. Two bullies, both bigger than you are, call you names and threaten you. I’m not going to look at them. I’m not going to talk to them. I’m going to ignore them and continue walking. I’m going to walk faster so that I can get home quickly and safely. Reinforcement, Maintenance, Generalization Self-management When someone teases me or challenges me, I ….. Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Don’t look X Don’t talk X Walk away X Tell my teacher Touchdown Reinforcement, Maintenance, Generalization Integrated curriculum (e.g., culturally specific literature, journal writing) Classwide and schoolwide instruction Collaboration with family and community members Group contingency As peer coach Affirmation For his good team work and leadership… By the power invested in Ms. Jones’ 3rd grade class… we hereby announce… James Brown as our very own Quarterback Reinforcing Appropriate Behavior “[B]ehaviors which are supported and recognized are the ones which will increase” (Rhode, Jenson, & Reavis, 1992, p. 27). “Good job, James, for following directions.” vs. “Stop it, James. You are interrupting the class.” If the student’s appropriate behavior does not increase, whatever you are doing is not reinforcing to the student (not working). James Academic Instruction Good teaching as first line of defense Many students’ problem behavior are results of poor academic achievement • “I can’t do the work. I’m bored. So let’s find something else to do!!” (academic escape) Good teaching produces “double” effects Good teaching requires Maximum number of instructional trials (fast pace + no down time) Students’ overt responses Error correction with repeated practice (Lambert et al., 2006) Early Identification Identify children at-risk as early as possible Children born into high risk situations considered for intervention from birth High quality in home and preschools programs • 4 and 5 year olds participating in a half day preschool had 32% fewer special ed placements (Conyers, Reynolds, & Ou, 2003) Early Academic Intervention School-based assessment to identify atrisk students Link between academic deficits and behavior problems Increased focus on early reading skills Dynamic Indicator of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBLES) • Focuses on phonemic awareness and oral reading fluency Importance of P.A. and ORF Students still behind in third grade rarely catch up to peers These skills should be assessed and taught early Research demonstrates intervention for PA and ORF successful in increasing targeted skills and reducing behavior disruptions (Kourea, Cartledge, & Musti-Rao, 2007; Koutsofats, Harmom, & Gray, 2008; Lane, Menzies, Munton, Von Duering, & English, 2005; Staubitz, Cartledge, Yurick, and Lo, 2005) Reading Intervention First-graders in two schools 6 boy and 2 girls Ages 6 to 8 years old African-American Low-income, urban schools Identified as “at-risk” • DIBELS winter benchmark Oral reading fluency scores All students were either “at-risk” or “some risk” Intervention Computer based reading program • • • • Focused on increasing reading fluency Repeated reading sequence Stand alone Supplemental reading curriculum Students used program: • 30 minutes per day • 3 to 4 times per week • 5 months (Jan to May) Results Oral Reading Fluency Rates (measured as correct words per minute) Treatment Generalization Student BL TX1 TX2 BL TX1 TX2 Lance 13 44 58 11 15 27 Stevie 11 51 70 8 14 25 Sheba 20 70 100 24 22 44 Ashley 28 70 80 22 36 50 Marvin 12 42 46 19 17 30 Clyde 16 52 70 22 20 41 Malik 15 64 74 24 28 43 Tyrone 20 61 71 27 34 38 DIBELS Winter and Spring Benchmarks Student DIBELS Winter DIBELS Spring 1st Grade-Benchmarks 1st Grade-Benchmarks ORF Risk Status ORF Risk Status Words Gained Lance 6 At Risk 21 Some Risk +15 Stevie 7 At Risk 21 Some Risk +14 Sheba 16 Some Risk 40 Low Risk +24 Ashley 15 Some Risk 49 Low Risk +34 Marvin 7 At Risk 21 Some Risk +14 Clyde 9 Some Risk 31 Some Risk +22 Malik 14 Some Risk 27 Some Risk +13 Tyrone 9 Some Risk 25 Some Risk +16 Summary of Results School 1 School 2 Tx Gen Tx Gen Baseline 16 CWPM 24 CWPM 18 CWPM 17 CWPM Intervention 52 CWPM 32 CWPM 63 CWPM 30 CWPM + 36 CWPM + 8 CWPM + 45 CWPM + 13 CWPM Gains 5 out of 8 students lowered risk status on DIBELS References Achilles, G. M., McLaughlin, M. J., & Croninger, R. G. (2007). Sociocultural correlates of disciplinary exclusion among students with emotional, behavioral, and learning disabilities in the SEELS national dataset. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 15(1), 33-45. Bradley, R., Doolittle, J., & Bartolotta, R. (2008). Building on the data and adding to the discussion: The experiences and outcomes of students with emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavior Education, 17, 4-23. Cartlege, G., & Kleefeld, J. (in press). Working together: Building children’s social skills through folk literature. Research Press Conyers, M. J., Reynolds, A. J., & Ou, S-R. (2003). The effects of early childhood intervention and subsequent special education services: Findings for the Chicago Child-Parent Centers. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25, 75-95. De Valenzuela, J. S., Copeland, S. R., Qi, C. H., & Park, M. (2006). Examining educational equity: Revisiting the disproportionate representation of minority students in special education. Exceptional Children, 72(4), 425-441 Drakeford, W., Cramer, E., Staples, J. (2006). Minority confinement in the juvenile justise system: Legal, social, and racial factors. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39 (1), 52-8. Ferguson, A.A. (2001). Bad boys: Public schools in the making of black masculinity. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. Kern, L., Hilt-Panahon, A., & Sokol, N. G. (2009). Further examining the triangle tip: Improving support for students with emotional and behavioral needs. Psychology in the Schools, 46(1), 18-32. Kourea, L., Cartledge, G., & Musti-Rao, S. (2007). Improving the reading skills of urban elementary students through total class peer tutoring. Remedial and Special Education, 28, 95-107. Koutsofats, A. D., Harmom, M. T., & Gray, S. (2009). The effects of a tier 2 intervention for phonemic awareness in a respons-to-intervention model in low-income preschool classrooms. Language Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 116-130. Lane, K. L., Menzies, H. M., Munton, S. M., Von Duering, R. M., & English, G. L. (2005). The effects of a supplemental early literacy program for a student at risk: A case study. Preventing School Failure, 50, 21-28. Losen, D.J., & Orfield, G. (2002). Racial inequality in special education. Cambridge, MA: Harvarrd Education Publishing Group. Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2006). Prediction of dropout among students with mild disabilities: A case for the inclusion of student engagement variables. Remedial and Special Education, 27(5), 276-292. Rhode, G., Jenson, W.R., & Reavis, H.K. (1992). The tough kid book: Practical classroom management strategies.Longmont, CO: Sopris West. Rice, E. H., Merves, E., & Srsic, A. (2008). Perceptions of gender differences in the expression of emotional and behavioral disabilities. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(4), 549-565. Sacks, G. & Kern, L. (2008). A comparison of quality of life variables for students with emotional and behavioral disorders and students without disabilities. Journal of Behavior Education, 17, 111-127. Staubitz, J. E., Cartledge, G., Yurick, A. L., & Lo, Y. (2005). Repeated reading for students with emotional or behavioral disorders: Peer- and trainer-mediated instruction. Behavioral Disorders, 31, 51-64. Thank You! Gwendolyn Cartledge cartledge.1@osu.edu Lenwood Gibson Gibson.476@osu.edu Starr Keyes Keys.20@osu.edu