Chapter 1

advertisement

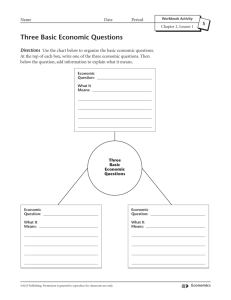

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: What Is Economics? © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 1 What Is Economics? Economics is the study of the choices made by people who are faced with scarcity. Scarcity is a situation in which resources are limited and can be used in different ways. 2 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Summary Slide Society’s Choices 3 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Society’s Choices Having a limited amount of resources means that we must sacrifice one thing in order to obtain another. The decisions of producers, consumers and government determine how an economic system answers three fundamental questions: 4 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Society’s Choices What goods and services do we produce? If we devote more resources to the production of one good, we have fewer resources for the production of another. 5 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Society’s Choices How do we produce these goods and services? How do we organize production and what methods and techniques should we use? 6 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Society’s Choices For whom do we produce the output? How should we distribute the output produced among members of society? 7 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Factors of Production Factors of production, or productive inputs, are the resources we use to produce goods and services: Natural resources Labor Physical capital Human capital Entrepreneurship 8 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Factors of Production Natural resources: The things created by acts of nature such as land, water, mineral, oil and gas deposits; renewable and nonrenewable resources. 9 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Factors of Production Labor: The human effort, physical and mental, used by workers in the production of goods and services. 10 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Factors of Production Physical capital. All the machines, buildings, equipment, roads and other objects made by human beings to produce goods and services. 11 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Factors of Production Human capital: The knowledge and skills acquired by a worker through education and experience. 12 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Factors of Production Entrepreneurship: The effort to coordinate the production and sale of goods and services. Entrepreneurs take risk and commit time and money to a business without any guarantee of profit. 13 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve The PPF curve is a graphical illustration of fundamental economic problems related to our ability to produce goods and services. The PPF curve shows the possible combinations of goods and services available to an economy, when resources are fully and efficiently employed. 14 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve When the economy is at point i, resources are not fully employed and/or they are not used efficiently. 15 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve Point h is desirable because it yields more of both goods, but not attainable given the amount of resources available. 16 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve Point e is one of the possible combinations of goods produced when resources are fully and efficiently employed. 17 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e At point e in this example, resources are devoted to the production of four space missions and 380 thousand computers. To increase the number of space missions by one, 80 thousand computers will have to be sacrificed. 18 O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e To increase the production of one good without decreasing the production of the other, the PPF curve must shift outward. From point f, an additional 150 thousand computers or two more space missions are now 19 possible. O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) Curve Resources are not perfectly adaptable. The PPF curve has a concave shape because resources are not perfectly adaptable in production. As we increase the production of one good, we sacrifice progressively more of the other. 20 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Microeconomics Microeconomics is the study of the choices made by consumers, firms, and government, and how these decisions affect the market for a particular good. Microeconomics focuses on the analysis of individual economic units. 21 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Microeconomics Microeconomic analysis can be used to: Understand how markets work and predict changes. Make personal or managerial decisions. Evaluate the merits of public policies. 22 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Microeconomics Microeconomics gives you the tools to analyze the impact of: Environmental regulations, taxes, imports, gender discrimination, labor unions, competition, patterns of production and consumption, and other decisions made by individual economic units. 23 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Macroeconomics Macroeconomics is the study of the nation’s economy as a whole. Macroeconomic analysis can be used to: Understand how a national economy works. Understand the grand debates over economic policy. Make informed business decisions. 24 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Macroeconomics Macroeconomic analysis can be used to understand important everyday economic issues such as: Unemployment, inflation, interest rates, exchange rates, the standard of living, the federal budget, consumption, and saving patterns. 25 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Economic Way of Thinking Economists use simplifying assumptions to eliminate irrelevant details and focus on what really matters. Assumptions are an aid to the analytical process. Simplifying assumptions do not have to be realistic. We use maps, for example, to get us from point A to point B knowing that the map is not an accurate description of the road ahead, but only an abstraction of reality. 26 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin The Economic Way of Thinking The “ceteris paribus” assumption is used to explore the relationship between two variables. A variable is a measure of something that can take on different values. “Ceteris paribus” is Latin for “all else the same.” To study the relationship between two variables, we assume that other variables do not change. 27 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Using Graphs and Formulas Suppose that a student receives a weekly income which consists of a $20 weekly allowance from her parents, and $4 per hour of work from her job. There is a linear relationship between hours worked and the student’s weekly income which can be described by the formula: W = $20 + ($4 x hours worked) 28 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Using Graphs and Formulas The expression W = $20 + ($4 x hours worked) can be illustrated as follows: 29 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Shifting the Curve If the student’s allowance or hourly wage change, the line’s intercept and slope will change, respectively. For example, an increase in her weekly allowance to $35 per week will shift the line upward by $15 for each previous number of hours worked. 30 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Negative Relationship Consider a consumer with a monthly budget of $150 who buys CDs at a price of $10 per CD. Each 5-unit increase in the amount of CDs decreases the amount left over for other goods by $50 (negative relationship). -50 vertical difference = 10 slope = 5 horizontal difference © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 31 Nonlinear Relationship There is a positive, nonlinear relationship between study time and grade on the exam. The second hour of study increases the grade by four points (from 6 to 10). But the ninth hour of study increases the grade by only one point (from 24 to 25). There are diminishing returns in study time. As study time increases, the exam grade increases at a 32 decreasing rate. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin