1 Carr Fanning et al

advertisement

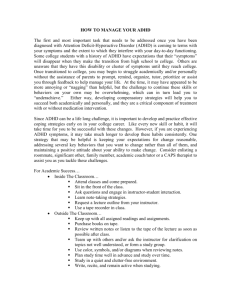

Using Student Voice to Escape the Spider’s Web: A Methodological Approach to De-victimizing Students with ADHD by Kate Carr-Fanning, Conor Mc Guckin, & Michael Shevlin Abstract After innumerable hours and weeks spent adrift on the ocean of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) literature, searching for answers among the biological and behavioural social sciences, an infuriating amount of questions with no answers remained. Far from scientific experts and their de-contextualized truth claims, the voice of one young man, plucked us from their spider’s web. When posed the question “what’s life with ADHD like?” he responded in kind, asking, “how does an elephant tell a mouse what it’s like to be an elephant?” Apparently an “insider” experiences barriers, just like an “outsider”, each seeking a way out and in. One can recognize the privileged nature of experiential knowledge (Beresford, 2003), and still appreciate that developmentally generative social interactions depend upon shared systems of meaning (Gergen, 1994). Realising “scientisms” (Thomas, 2009) inability to explicate either began the construction of the student voice methodology delineated in this paper. Student voice (i.e., voice) poses significant challenges and transformative potentials (Bragg, 2007); it is further problematized, and necessary, when it involves students with ADHD. Voice is inherently about power and knowledge (Thomas, 2011). As such, the social meaning of ADHD (Singh, 2012) must be considered to avoid revictimizing the voices of students with ADHD (i.e., ADHD voice) or reproducing conventional knowledge (Fielding, 2004). This paper provides a pertinent analysis of voice methodology, and the limitations in prior ADHD voice research. The theoretical framework for the current study will also be explained, that is, the construction of a “counter-discourse” to engage in meaningful dialogue (Taylor & Robinson, 2009). Introduction This paper examines the methodology for exploratory ADHD voice research. At the outset, an explanation of what we have termed the metaphorical “spider’s web” is necessary; because it is fundamental, not only to the paper, but also the construction of the research methodology. Ultimately, voice is about power and knowledge (Thomas, 2011); but there are many ways of knowing, or systems of meaning (Sexton, 1997); just as there are many ways of listening to the diverse array of voices which exist across and within students (Cook-Sather, 2006). The metaphor of the spider’s web was introduced in the lyrics of Ralph Mc Tell’s song, “Michael in the Garden”; which illustrates the existence and consequences of divergent frameworks for meaning: Out in the garden . . . Michael is crying. Caught in a spider’s web, its broken wings beating, a butterfly dying. And they in their wisdom say ‘Michael’s got something wrong, wrong, wrong with his mind’. Well they must be blind, if they can’t see what Michael sees . . . Michael where are you? Michael where are we, We who see that there’s something wrong with your mind . . . Oh Michael sees all Behind the high walls Surrounding his kingdom, Whilst we in our wisdom Still trapped in the spider’s web Far from the flow and ebb Of life in the garden . . . But Michael has pardoned Us for he sees That really he’s free And there’s nothing to mend For his wings are not broken. Evidently, Mc Tell realized the multiplicity in meaning-making, and advocated a recognition and respect for the diversity in voice. Thereby, raising the question of “whose truth” is prioritized, enforced, and sustained by the taken for granted “realities” (Gergen, 2002). More importantly, however, this song illustrates the potential danger of speaking “about” and “for” others, especially in assumptions of competency (Alcoff, 1992). This is evident in Mc Tell’s depiction of the effects of the spider’s web on those constructed and are constricted by it. Yet there is also appreciation for Michael’s ability to live embedded within but also beyond its confines, which represents the transformative potential of voice. A student’s perception of lived experiences will be based on the “meaning” which events have to them (Mackay, 2003). Student-centric meaning is individualized (Rogers, 1951). Thus, voice provides adult outsiders with alternative perspectives on taken for granted social structures (Rudduck & Flutter, 2003). However, inasmuch as personal constructs determine perception, research methods shape what is (and can be) discovered in research (Crotty, 1998). Thus, Michael is also potentially vulnerable to becoming tangled in the web and his wings broken. The existence and impact of systems of meaning requires methodology to critically analyse constructs used in research and practice. Therefore, methodology drew on theory from Social Constructionism (SC) and Constructivist Psychology (CP), which like structure and agency are inextricable (Paris & Epting, 2004). Consultation with students requires abandoning conventional knowledge (Cook, 2011). Nowhere is this more necessary than with ADHD voice, because the meaning of ADHD in research and life has the potential to re-victimize students labelled as such (Singh, 2012). Labels are socio-political (Thomas & Loxley, 2005), pathologizing (Maddux, 2011), stigmatising (Singh, 2012), and ambiguous (Clough et al., 2005) constructs; this is the metaphorical spider’s web, so-called because they ensnare the minds of people and groups, constricting their thoughts and practises (Lock & Strong, 2010). This paper may critique the ADHD-label specifically, but all categorical practices are subject to similar reproach, indeed, the spider’s web impacts (to varying degrees) all inclusive practices. Despite the consequences of the spider’s web, especially for those who do not “fit in” with its established version of reality (Thomas & Loxley, 2005), one cannot escape webs, because meaning is required for interaction (Gergen, 2002). Evidently, voice is conceptually and methodologically challenging, and there is a lack of theoretical knowledge (Taylor & Robinson, 2009) and information regarding “how” to achieve “authentic” and “meaningful” (Rudduck & Flutter, 2006) “consultation” (Taylor & Robinson, 2007) “with” students (Rose & Shevlin, 2008). Notwithstanding obstacles, voice holds transformative potential (Bragg, 2007). Consequently, a methodological approach requires the construction of a neutral space, wherein the student and researcher can engage in collaborative dialogue, beyond the effects of the spider’s web (Taylor & Robinson, 2007). CP supports this, because it studies how people and groups construct systems of meaning and their consequences (Raskin, 2002). As addressed subsequently, a space of neutral meaning can be provided by Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC). The study of stress and coping de-victimizes ADHD voice, by exploring their embodied experiences of oppression (Reeves, 2012); and studying “needs”, free from the framing effects of “labels” (Aldwin, 2009). Another transactional model, Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) Bio-ecological Model (BEM), contextualises students’ psychoemotional experiences of barriers (problems) and facilitators (solutions) to participation; thereby, contributing to psychological knowledge for inclusion (Hick, Kershner, & Farrell, 2009). People and groups are engaged in constructing, and then being constricted, by the metaphorical spider’s web. There are significant and long lasting consequences for students who do not fit-in with normative rules for development and behaviour. However, voice can be used as a tool to escape and reconstruct its effects. Therefore, the problematic nature and limited theoretical knowledge regarding voice, does not outweigh its transformative potential. Using a combination of transactional models a theoretical framework can create a counterdiscourse to engage in meaningful dialogue, in order to reconstruct knowledge and practice, and move beyond the spider’s web towards a transformative agenda (Freiler, 2003). First, however, current knowledge and practices require consideration. Reconstructing Inclusion According to SC, knowledge (i.e., meaning) is never “discovered” (Crotty, 1998), it is coconstructed transactionally between active-agents and their socio-environmental contexts across time (Lock & Strong, 2010). This section considers how voice and CP can contribute to a “reconstruction”, rather than a “deconstruction”, of inclusive knowledge and practice (Raskin, 2002). Inclusion Agenda Voice’s concern with power and knowledge adopts a similar stance on the social structures inclusionist ideology also disavows (Finkelstien, 2001). However, voice is further complicated by emancipatory agendas (Corbett, 1998). Thus, we must begin by locating the thesis within the broader inclusive, constructivist, and transactional paradigms. Modernity ascribes to inclusion, which includes ideology (Finkelstien, 2001), legislation (e.g., Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act, 2004), and implications for practice (e.g., National Council for Special Education: NCSE, 2005); these numerous interpretations evidence that meaning is not absolute or universal (Sharry, 2004). Indeed, inclusion recognized the consequences of social perception, and deliberately attempted to reconstruct structural influence on agency, by shifting focus from oppression to emancipation (Shakespeare & Watson, 2002). Nevertheless, causal reductionism, whereby disability is caused by social structures (i.e., barriers to participation) or with-in student deficits cannot explicate social phenomenon; because structure and agency are fundamentally and existentially related (Paris & Epting, 2004). Inclusionist orientation champions transactionalism’s “goodness-of-fit” hypothesis, whereby, Special Educational Needs (SEN) arise from a mismatch between the person’s capabilities, and the opportunities and demands present in the environment (i.e., P-E fit). This approach is embodied in the BEM (Bronfenbrenner, 2005) adopted by the National Children’s Strategy (NCS, 2000); and considered best-practice for inclusive education (NCSE, 2006), including Emotional Disturbance and/or Behavioural Disorders (EBD), which ADHD is subsumed under (Special Education Support Services: SESS, 2009). Clearly, inclusion appreciates the consequences of meaning on how people and groups respond to differences; and advocates a reconstruction of such influences. Nevertheless, one cannot focus on external social structures alone; it is the P-E fit which causes SEN. Interactions require systems of meaning, and so these must be considered. Whose Label is This? Beginning with an exploration of the constructivist stance adopted, this section introduces concepts central to the theoretical framework considered subsequently. Critical examination of systems of meaning and the spider’s web is necessary, because understanding “the problem” requires an appreciation of the whole situation and forces distributed therein (Lewin, 1935). All interactions depend upon meaning, thus, their impact in research and practice requires consideration. This critique advocates the reconstructing the meaning of ADHD, referred to herein as moving beyond the spider’s web. Constructing Meaning As meaning is a powerful inevitability, considering the boundaries of meaning, such as those involved in inclusion, suggests a reconstruction of the spider’s web may be preferable to its deconstruction. Research cannot study objective reality, neither can it investigate structure independent of agency. Consequently, research must consider the relational structures involved in interaction (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). Constructed to facilitate interaction, systems of meaning become the most fundamental situational forces (Mackay, 2003; Raskin & Bridges, 2004); because: “. . . frames (ways of seeing or defining situations) and the labels attached to them dictate (to a greater or lesser extent) what we can see and do . . .” (de Shazer, 1985, p. 40). Meaning construct perception and experience, and is used to guide action (Sharry, 2004), and people’s behavior tends to conform to their beliefs (Bandura, 1977). Thus, in the oft cited words of Thomas and Thomas (1928), “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” (p. 571-572). Evidently, the impact of the spider’s web on perception and response is considerable. Labels are not inherently “true”, nor are they “bad”, they only have utility relative to practice (Raskin, 2002). Watts (1951) illustrated this conundrum, when he posed the question as to whether rabbits should be classified by fur or meat. As both systems are be true, the choice would differ for furriers and butchers, because one would be more useful, and utility depends upon goals. Inclusion’s goal is to shift attention to values and commitments to social justice (Norwich, 2007). Therefore, bio-medical labels are criticized from individualized approach to “curing” the “broken” student, and neglecting the environment (Griffin & Shevlin, 2007). Inasmuch as inclusionist research agendas are subject to similar reproach for its sociological focus on external oppression (Watermeyer, 2012). Meaning can be oppressive or emancipatory (Freire, 1997), however, it is also involved in participation, and belonging (Nussbaum, 2007). Thus, truth may not exist without power (Foucault, 1994), but neither does meaning or interaction (Gergen, 2002). Hence, SC is about more than emancipation from oppression (Haslam & Reicherm, 2012), it is inherent in the re-framing of problems and solutions (Gingerich & Wabeke, 2001) and/or multi-voice perspective (Thomas, 2011); because power exists is various dynamic and reciprocal forms in all interactions (Engestrom, 2003). Evidently, labels are not the problem, because meaning is required for interaction, and labels assume power as given. Therefore, the uncritical reliance upon inappropriate labels prevents inclusion. A critical evaluation of the spider’s web, illustrates the problems inherent using bio-medical labels in inclusive practice. The Spider’s Web From a CP perspective, the ADHD-label must be evaluated based on its utility for achieving inclusive goals; and understood in terms of meaning, perception, and experience. This critique is concerned with analysing the ADHD-label’s viability for inclusive practices. Despite being the most common (Polancsyk et al., 2007) and well researched condition (Taylor, 2009), knowledge of ADHD is predominantly based on bio-medical evidence, discovered in clinical research (NICE, 2009), using behavioural descriptions (e.g., hyperactive), which lack ecological validity (Armstrong, Galloway, & Tomlinson, 1993). Therefore, ADHD is a bio-medical label and explanation (Taylor, 2009) for a biopsychosocial condition (Cooper, 1997). Medicalization is problematic when it is applied outside clinical settings (Hyman, 2010; Shah & Mountain, 2007). It is perhaps unsurprising then that ADHD knowledge in practice is inaccurate (Furnham & Sawar, 2010), stigmatizing (Singh, 2012), and contested (Hinshaw et al., 2011). Hence, psychosocial research is needed, which must consider the transactions between the perceived (subjective) and actual (objective) environment (Jessor, 1991). As such, the dearth of qualitative research (NICE, 2009), especially in the context of these students daily lives (Gallican & Curle, 2008) must be addressed. In school, students with ADHD are given a second, notoriously problematic, EBDlabel, so educators know what SEN to expect (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). Lacking any utility for teachers and students, the EBD-label may hinder more than help (Clough et al., 2005). No other student group is perceived as negatively or excluded more readily (Cooper, 2011). Apparently, the only benefit is for administration (Norwich, 2008). Therefore, the EBD-label is not a viable means to inclustionist goals. However, contrary to debate (e.g., Norwich, 2008) there is no dilemma about “if” people should recognize difference. Recognition is inevitable, people and groups will always construct stories to cope with difference (Furnham, 1998). The meaning, however, is and has been subject to change (Griffin & Shevlin, 2007). The proposed deconstruction of medical (i.e., spider’s web) knowledge, and a return to teachers conventional wisdom (e.g., Thomas, 2009) is problematic; given that teachers implicit beliefs (e.g., attitudes) are themselves barriers to participation (e.g., McDonnell, 2003). Conversely, the issue is non-recognition (hidden) and/or mis-recognition (stereotyping), because without respect for diversity, students will be oppressed and marginalized by systems of meaning (Lynch & Lodge, 2003). Indeed, the existence and/or awareness of the ADHD-label is not required for stigma. Students in the US interpreted ADHD-type behaviours as “crazy” or “stupid” (Law, Sinclair, & Fraser, 2007); and findings suggest similar negativity in Ireland (O’Driscoll et al., 2010). Students with ADHD are aware of these discriminatory attitudes (Singh, 2012), they often report feeling rejected and misunderstood (e.g., Gallican & Curle, 2007), and describe themselves as “wacko” and “different” (Kendall et al., 2003). However, the “normal” or “ADHD” student is not an inherent truth, but a belief about oneself, socially constructed, communicated and reinforced by social interaction (Rogers, 1951). Social interactions can be developmentally generative (e.g., participation) or dysfunctional (e.g., oppression: Bronfenbrenner, 2005). ADHD poses unique challenges to different stakeholders, so they often have conflicting definitions of the problem and solution (Kildea, Wright, & Davies, 2011). In the absence of shared meaning, dysfunctional interactions preventing inclusion (Huges, 2007) become “vicious cycles” (Gallichan & Curle, 2008). Indeed, perception is determined by personal beliefs and goals in the context of a situation (Parks & Folkman, 1997). Consequently, inclusive practices must be based on shared meaning (Freiler, 2003). This critique of the metaphorical spider’s web illustrates the re-victimizing consequences of current meaning associated with ADHD. Whether the label is ADHD, EBD, wacko, or stupid, the meaning impacts stakeholders perceive, experience, and respond to events. One cannot study events in reality, and since a way of seeing is a way of not seeing, the spider’s web prevents adult-outsiders seeing “what Michael sees”. Therefore, in the reconstruction of the spider’s web, it is paramount for de-victimized ADHD voice be explored. Student Voice The current re-victimizing meaning of ADHD has been informed by research conducted “on” or “about” students (Rose & Shevlin, 2004). However, students with ADHD can (Singh, 2007) and should (Nations Conventions Rights of the Child, 1989) be consulted on matters concerning them. The question, therefore, it about “how” to elicit and interpret voice (Robinson & Taylor, 2009). This section explores concepts of power and meaning, because they represent voice’s methodological challenge and its transformational potential (Fielding & Rudduck, 2002). The critique of prior ADHD voice research illustrates the re-victimizing consequences of conventional knowledge in research. De-victimized Consultation The spider’s web traps students, teachers, and researchers in dysfunctional self-perpetuating cycles. In order to escape from its confines adults must adjust how they “see” students and interpret their voice (Bragg, 2007). Student-centred concepts of inside-experts, appreciates they have a unique relationship with their world, unimaginable to outsiders (Alcoff, 1992; Fielding, 2004; Rogers, 1951). Therefore, voice supports inclusive practices by proffering different perspectives; it enables adults to re-frame how they perceive socio-environmental structures (e.g., Flutter & Rudduck, 2003). More importantly, however, while students are embedded within the spider’s web (Robinson & Taylor, 2009), they are not similarly subject to its framing effects. According to Wright and Lopez (2011), outsider’s perceptions are predisposed toward other people’s abnormal / negative behaviours and labels, which obscures the socio-environmental context. Whereas, life on the inside looking out provides a different perceptual field entirely. The salient features are the socio-environmental structures which make life better or worse. Hence, voice provides perspectives which are experiential, culturally, and contextually bound. Thus, voice can be used to escape the spider’s web, and reconstruct the meaning of ADHD. A prerequisite to voice is critical reflection on conventional knowledge and assumptions; because frames determine what voice is elicited and whose voice gets heard (Hunleth, 2011). Student consultation refers to “formal involvement” (NCS, 2000), because voice recognizes rights and competency (Thomas, 2008). Therefore, rather than antiquated, oppressive, and paternalistic notions of incompetent and passive “becomings”, voice advocates students-as-agentic “beings” (Bragg, 2007). Agents are “empowered” because they are free from control (emancipated) and competent self-determiners (Adams, 2008). If students are actively involved in research and meaning construction, one cannot “give” them power/voice (Toynbee, 2009). However, people have access to different types of power (Robbson & Taylor, 2009). Indeed, disaffection (Hartas, 2011), challenging behaviour (Munn & Lloyed, 2008), even silence (Lewis, 2010) are all ways of having power/voice. One cannot give power, but relational structures can disempower and re-victimize students (Arnot & Reay, 2007). Thus, voice can be used to re-enforce adult agendas (Fielding, 2001) and social norms (Bragg, 2007). The student has multiple voices, and ascertaining which is engaged in dialogue is prohibitive (Cook-Sather, 2006). Authentic voice is “eclipsed” when the research does not consider student’s competency (Cook, 2011); which is as critically as it is challenging (Hunleth, 2011). Competencies develop with age (James, Jenks & Prout, 1998), educational opportunity, and/or psychobiology (Robinson & Taylor, 2009). Conventional systems of meaning (e.g., language) and modes of interaction (e.g., expectations), especially those from the adult world, must be dis-guarded; or risk patronizing, restricting, and/or alienating voice (Christensen & James, 2000; Fielding, 2001, 2004). However, in order to reconstruct the spider’s web, one must engage in dialogue (Gergen, 1994). Dialogue requires shared meaning, however, what is personally “known” about that meaning is privilaged (Komulainen, 2007). Inevitably, equal partnership is more aspiration than objective (Fielding, 2004). Nevertheless, power is inherent in any interaction, and even if students possessed the monopoly on truth, adults would never fully grasp it (Punch, 2002). Insiders provide unique insights but have “blind spots” (Osler, 2006); thus, they are essential and insufficient (Oliver, 2000). Ultimately, the goal is multi-voice, because it holds transformational potential (CookSather, 2006; Gergen, 1994). Hence, the student is viewed herein as an expert consultant, and methodology sought meaningful dialogue (Cook, 2011). The outcome of dialogue cannot be “pure” student perspective, nor does it exist free from conventional meaning (Komulainen, 2007). However, in the co-constructing of knowledge for practice, it is essential that dialogue occurs beyond the effects of the spider’s web (Clark & Moss, 2001; James, 2007). Re-victimizing ADHD Voice Insanity, it is said, is doing the same thing again and again expecting a different result (Brown, 1983). The madness of previous ADHD voice research, however, can be attributed to the consequences of conventional social relations. Scientific and conventional knowledge exist within social relations, and so researchers experience problems working within confines (e.g., spider’s web) without being limited by (or reproduce) them (Harding, 1991). This section demonstrates how uncritical reliance on labels, prevented researchers seeing students as beings, living beyond the spider’s web; which re-victimized their voice. The extremely limited (NICE, 2009) extant literature is not ADHD voice per-say. The findings reviewed herein refer to qualitative research with young people, usually in clinical settings (Gallican & Curle, 2007). Any frame (or method) has consequences for research, but dialogue requires shared meaning. Therefore, frames require evaluation, because they can manipulate voice in its elicitation and/or interpretation (Fielding, 2004). Despite the re-victimizing effects of the ADHD-label, explored above, all previous research used the ADHD-frame during interactions (e.g., interviews). In the context of research, the student’s interpretation of meaning constructs their voice (Hunleth, 2011). Using the spider’s web as a frame, when students are malleable and open to suggestion, structured the parameters and contents of dialogue (Porter & Lewis, 2005). Consider the dominant findings, from the USA (e.g., Kruger & Kendall, 2003) and UK (e.g., Cooper & Shea, 2006), which suggests the existence of an ADHD-identity. Apparently, students cannot differentiate between their self-concept, challenging behaviour, and the ADHD-label. An ADHD-identity would mean full internalization of the meaning of ADHD. But the meaning of a disability is reported to be different for insiders (Wright & Lopez, 2009). Findings suggest that the ADHD-label has limited (Dunne & Moore, 2011) or non-existent (McIntyre & Hennessy, 2011) meaning, beyond that they have been identified as broken or disordered (Wearmounth, 1999). During an interview, interaction depends on meaning, which one cannot assume is shared (Komulainen, 2007), nor can the voice engaged be ascertained (Cook-Sather, 2006). Therefore, investigating voice using the ADHD-frame, could be eliciting information regarding perception and experiences of being labelled disorders. However, it does not explore student’s needs, nor does it consider what works in practice. Students respond to the parameters set by the researcher, and the more re-victimizing consequences of the ADHD-frame is apparent in a UK study by Kildea, Wright, and Davies (2011). Research began within SC, but shifted paradigm mid-way, because the participants all reported similar ADHD symptoms. Researchers concluded that this was proof of the disorder’s material reality. Notwithstanding a biological basis to ADHD (Taylor, 2009), their argument is fundamentally flawed. In order to support their conclusion, people with ADHD must be able to accurately self-report shared symptomatology. Conversley, ADHD is associated with perceptual bias impeding self-reporting (e.g., Hoza et al., 2004), and symptomology varies considerably across people (Taylor, 2009). A more unified construct is the “ADHD student”. Therefore, using the spider’s web as the frame impacted what research could (and did) discover. Consequently, the conclusions actually re-victimized students, because they reproduced conventional knowledge of ADHD. Evidently, power, meaning, and voice are a relational process; which holds transformative or re-victimizing potentials. Engaging voice/power requires systems of meaning to be reconsidered, because assumptions and conventional knowledge impacts how voice is elicited and interpreted. Previous ADHD voice research was limited by researchers’ inability to consider lived experiences beyond the spider’s web. Frames simultaneously reveal and conceal, one cannot escape the spider’s web using it to structure dialogue. Thus, ADHD voice became trapped voice within the spider’s web, and these students were revictimized once more. Consequently, methodology needed to construct a theoretical framework supporting de-victimized consultation. De-victimizing ADHD Voice Voice is methodologically challenging, since experiential knowledge is paramount but privileged, an outsider will never be an insider. ADHD voice, however, is considerably more problematic, but the label’s re-victimizing effects also makes consultation more necessary. The objective is the obstacle, because it is difficult to explore the experiences of students with ADHD, without becoming tangled in the spider’s web. The theoretical framework, which incorporated two transactional models, is explored in this section. A neutral meaning framework, or counter-discourse, was provided by exploring student’s perceptions and experiences of stress and coping. Contextualizing ADHD voice using a bio-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 2005), facilitated the identification of problem (barriers) and solutions (facilitators) to participation; thereby, contributing to a reconstruction of inclusive knowledge and practice. Stress: the space for voice Methodology required conventional systems of meaning and power be critically evaluated. However, theory is also cognizant that meaning is an inevitable necessity, simultaneously concealing and revealing, it creates barriers for outsiders and insiders alike, trapping both within the spider’s web. This section examine the space for voice provided by the TMSC (Lazarus, 1991). Undoubtedly, we are all more “. . . human than otherwise . . .” (Sullivan, 1953, p. 4), and herein lies the key to inclusion and moving beyond the spider’s web. Everyone is engaged in a continuous process of negotiation between their own capabilities and goals, relative to environmental opportunities and demands (i.e., P-E). The study of stress and coping explores this adaptational process. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) TMSC, stress is experienced when a person “perceives” environmental demands as exceeding personal resources. In inclusionist terminology, barriers to participation are experienced as distress; because the problem is neither the square peg nor the round hole, it is the experience of forcing the former into the latter (Reeves, 2012). The meaning-making process involves cognition and emotion (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). Emotions communicate the personal significance of a P-E transaction (Lazarus, 1991, 2000). Unfathomably, however, research has avoided the psycho-emotional experience of disability. Instead, prioritizing reductivist and disempowering framework, on the external structures of oppression (Watermeyer, 2012). However, meaning is relational, both structure (social) and agency (personal) are involved (Paris & Epting, 2004). Exploring stress is methodologically beneficially, because stress (the problem) is characterized by the P-E relationship (Lazarus, 1991), but is social in origin (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Therefore, instead of targeting student-deficits, one considers the mismatch between demands and resources (Aldwin, 2009). Consequently, the implied solution is a reconstruction of current relational systems causing stress. The study of stress in young people with ADHD (e.g., Gallican & Curle, 2008) and other disorders (Davidson, 2010), has tended to use the label as the pre-identified stressor. The re-victimizing effects of frames used in research was explored previously. Pursuant to de-victimizing ADHD voice, the current research is exploratory; Bronfenbrenner (2005) would say it is in the “discovery mode”. Psychosocial research is challenging, Winkle, Saegert, and Evans (2009) advocate the insider self-identify the salient features within the PE interaction. Hence, no presuppositions were formed about student’s experiences of stress and coping; save that all students experience stress, which arises from a mismatch between resources and demands (Lazarus, 1991). Consequently, research adopted a counter-discourse (Taylor & Robinson, 2009) or a different framework for listening (Clark & Moss, 2001). Questions were free from adult-power-agent constructs and the spider’s web (Fielding, 2004), but were still meaningful (Porter & Lewis, 2007) without assuming shared meaning (Komulainen, 2007). There was space for voice, because stress is constructed in context based on personal meaning and goals (Parks & Folkman, 1997). Furthermore, coping responses are all cognitive and behavioural efforts to remove distress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Thus, utility is determined by student’s goals, rather than socially normative expectations for behaviour (Parks & Folkman, 1997). Moreover, an understanding of personal-strengths (e.g., coping responses) and/or environmental solutions (e.g., social resources) can contribute to inclusive knowledge of what works in practice (Gingerich & Wabeke, 2001; Shah & Mountain, 2007). In order to contribute to knowledge and practice, one must recognize the socio-environmental context wherein voice emerges and is imbued with meaning (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). This is not antithetical to the TMSC, because according to Lazarus (2000) the perception of stress is a functionally viable interpretation of actual events. The limitation, however, is the model is psychological, and does not provide a framework to explore the socio-environmental structures. However, a psychosocial approach requires one to consider both the perceived and actual environment (Jessor, 1991). De-victimized ADHD voice required that students self-identify salient features within P-E interactions. Therefore, the current research explores student’s perceptions of stress, which emphasises needs free from the framing effects of the spider’s web. The study of coping champions a re-framing of events in terms of strengths and solutions, and so contributes to knowledge of what works in inclusive practice. Further to this, reconstructing the spider’s web requires the contextualization of voice. Voice-in-Context The research methodology emphasised de-victimized ADHD voice. But in order to move beyond theory and into practice, voice requires contextualization (James, 2007; Mc Guckin, & Minton, in press); within what MacMahon, Pugh, and Ipsen (1960) appropriately termed the “web of causation”. A social interaction includes multiple stakeholders and valid voices. Rather than identifying and promoting one truth, inclusion requires the co-construction of shared meaning. Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) BEM provides a model to explore voice within its socio-environmental context. The social ecology is conceptualized as an array of “nested” interconnected systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). At its analytic-centre, is the active-agent interacting within the “micro-system”, subject to forces at distal and proximal levels, within the ever widening social systems (e.g., meso- and chrono-system). Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) conceptualization of agency correlates to principles of voice (Bragg, 2007), and is experientially similar to TMSC (Lazarus, 1991). Its methodological contribution is an empirical framework to study P-E transactions. The experience of disablism is essential (Watermeyer, 2012), however, human experience is an “emergent whole” (Tomisini, 2012), where objective and subjective “emerge as partners” (Crotty, 1998). According to Bronfenbrenner (2005), research needs to focus on “processes”, that is, the tools for interaction between the P-E, which shape experience and behaviour. Using the concept of “ecological niches”, research can evaluate processes and P-E fit across contexts. This is facilitated by triangulating the voices of multiple stakeholders. In moving beyond the spider’s web, one must recognize that meaning is necessary for interaction, and shared meaning is fundamental to inclusion (Gergen, 2002). Therefore, voice should aspire to relational structures which promote recognition and acceptance, and so, support participation and belonging (Lynch & Lodge, 2002). This review of the theoretical framework examined methodology’s constrution of neutral space for ADHD voice. Investigating student’s perceptions and experiences of stress and coping, engages voice in meaningful dialogue about problems and solutions to inclusion. Further, ADHD voice is de-victimized, because needs are studied free from the effects of the spider’s web. Nevertheless, the objective is not de-constructing the spider’s web, but rather the reconstruction of current relational systems. Consequently, voice requires triangulation and contextualization within the Irish social ecology. This theoretical framework has informed the research methods (e.g., data collection) for a multiple qualitative case study. This approach appreciates the “boundedness” between structure and agency, and is oriented towards solving problems in real world settings (Stake, 2005). References Adams, R. (2008). Empowerment, Participation and Social Work (4th Eds.). New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Alcoff, L. (1992). The problem of speaking for others. Cultural Critique, 20, 5–32. Aldwin, C. (2009). Stress, Coping, and Development: An Integrative Perspective (2nd Eds.). New York: the Guilford Press. Armstrong, D., Galloway, D., & Tomlinson, S. (1993). Assessing special educational Needs: The child's contribution. British Educational Research Journal, 19(2), 121-31. Arnot, M. & Reay, D. (2007). A sociology of pedagogic voice: Power, inequality and pupil consultation. Discourse. Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 28(3), 311-325. Avramidis, E., & Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(2), 129-147. Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press. Beresford, P. (2003). It’s Our Lives. London: Citizen Press. Bragg, S. (2007). Consulting Young People: A Review of the Literature. UK: Creative Partnership. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making Human Beings Human. California: Sage. Brown, R. M. (1984). Sudden Death. New York: Bantam. Christensen, P. & James, A. (2008). Research with Children. New York: Routledge. Clark, A. & Moss, P. (2001). Listening to Young Children: The Mosaic Approach. London: National Children’s Bureau. Clough, P., Garner, P., Pardeck, J. T., & Yuen, F. (2005). Themes and dimensions of EBD: A conceptual overview. In P. Clough, P. Garner, J. T. Pardeck, & F. Yuen (Eds.), the SAGE Handbook of Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (pp. 3-19). London: Sage. Cook, T. (2011). Authentic voice: The role of methodology and method in transformational research. In G. Czerniawski & W. Kidd (Eds.), the Student Voice Handbook (pp. 307330). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group. Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry 36(4), 359 – 390. Cooper, P. & Shea, T. (2006). Pupils perceptions of ADHD. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 3(3), 36-48. Cooper, P. (1997). Biology, behaviour and education: ADHD and the bio-psycho-social perspective. Educational and Child Psychology, 14(1), 31-38. Cooper, P. (2011). Teacher strategies for effective intervention with students presenting social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 26(1), 71-86. Corbett, J. (1998). ‘Voice’ in emancipatory research: Imaginative listening. In P. Clough & L. Barton (Eds.), Articulating with Difficulty (pp. 54–63). London: Paul Chapman. Crotty, M. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London: Sage. Davidson, R. (2008). Child first, sibling second: The experience of children with a chronically ill brother or sister. Masters Thesis, University College Dublin. de Shazer, S. (1985). Keys to Solution in Brief Therapy. New York: Norton. Dumit, J. (2006). Illnesses you have to fight to get: Facts as forces in uncertain, emergent illnesses. Social Science and Medicine, 62(3), 577-590. Dunne, L. & Moore, A. (2011). From boy to man: A personal story of ADHD. Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties, 16(4), 351-364. Engestrom, Y. (2003). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engestrom, R. Miettinen, & R-L. Punamaki (Eds.), Perspectives on Activity Theory (pp. 1-38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Fielding, M. & Rudduck, J. (2002, September). The Transformative Potential of Student Voice: Confronting the Power Issues. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, England. Retrieved: http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002544.htm Fielding, M. (2001). Beyond the rhetoric of student voice: New departures or new constraints in the transformation of 21st century schooling? Forum, 43(2), 100-110. Fielding, M. (2001). Students as radical agents of change. Journal of Educational Change 2(3), 123-141 Fielding, M. (2004). Transformative approaches to student voice: Theoretical underpinnings, recalcitrant realities. British Educational Research Journal, 30(2), 295–311. Finkelstein, V. (2001). A Personal Journey into Disability Politics. First presented at Leeds University Centre for Disability Studies, retrieved from URL: http://www.independentliving.org/docs3/finkelstein01a.pdf Flutter, J. & Rudduck, J. (2004). Consulting Pupils: What’s in it for Schools? London: Rutledge. Foucault, M. (1994). Two lectures. In N. Dirks & S.B. Ortner (Eds.), Culture, Power, History (pp. 200-221). Princeton: Princeton University Press. Freiler, C. (2003). From Experiences of Exclusion to a Vision of Inclusion. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsd.ca/subsites/inclusion/bp/cf2.htm. Freire, P. (1990 [1971]). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. Bergman Ramos, trans.). New York: Continuum. Furnham, A. (1988). Lay Theories. New York: Pergamon. Furnham, A., & Sarwar, T. (2011). Beliefs about attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 24(4), 301-311. Gallichan, D. J. & Curle, C. (2008). Fitting square pegs into round holes: The challenge of coping with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(3), 343-363. Gergen, K. J. (1994). Realities and Relationships, Soundings in Social Construction. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Gergen, K. J. (2002). Social Construction in Context. London: Sage. Gingerich, W. J., & Wabeke, T. (2001). A solution-focused approach to mental health intervention in school settings. Children & Schools, 23, 33-47. Government of Ireland (2004). Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act. Dublin: The Stationery Office. Griffin, S. & Shevlin, M. (2007). Responding to Special Educational Needs: An Irish perspective. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? Thinking from women’s lives. New York: Cornell University Press. Hartas, D. (2011). Young people’s participation: Is disaffection another way of having a voice? Educational Psychology in Practice, 27(2), 103-115. Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2012). When prisoners take over the prison: A social psychology of resistance. Personal Socical Psychology Review, 16, 152–179. Hick, P., Kershner, R., & Farrell, P. (2009). Psychology for Inclusive Education. Oxford: Routledge. Hinshaw, S. P., Scheffler, R. M., Fulton, B.D., et al. (2011). International variation in treatment procedures for ADHD: Social context and recent trends. Psychiatric Services, 62, 459-464. Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., et al. (2004). Self-perceptions of competence in children with ADHD and comparison children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 382–391. Hughes, L. (2007). The reality of living with AD/HD: Children’s concern about educational and medical support. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 12(1), 69 — 80. Hunleth, J. (2011). Beyond on or with: Questioning power dynamics and knowledge production in ‘child-oriented’ research methodology. Childhood, 18(1), 81-93. Hyman, S. E. (2010). The diagnosis of mental disorders: The problem of reification. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 155-179. James, A. (2007). Giving voice to children’s voices: Practices and problems, pitfalls and potentials. American Anthropologist, 109, 261–272. James, A., Jenks, C. & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press. Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12, 597-605. Kendall, J., Hatton, D., Beckett, A., & Leo, M. (2003). Children’s accounts of attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Advances in Nursing Science, 26(2), 114–130. Kildea, S., Wright, J., & Davies, J. (2011). Making sense of ADHD in practice: A stakeholder review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(1), 1-25. Komulainen, S. (2007). The ambiguity of the child’s ‘voice’ in social research. Childhood 14(1), 11–28. Kruger, M. & Kendall, J. (2001). Descriptions of self: An exploratory study of adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 14(2), 61-72. Law, G. U., Sinclair, S., & Fraser, N. (2007). Children’s attitudes and behavioural intentions towards a peer with symptoms of ADHD: Does the addition of a diagnostic label make a difference? Journal of Child Health Care, 11(2), 98-111. Lazarus R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press. Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 234-247. Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Toward better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55, 665-673. Lewin, K. (1935). A Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: McGraw-Hill. Lewis, A. & Porter, J. (2007). Research and pupil voice. In L. Florian (Eds.), the SAGE Handbook of Special Education (pp. 223-234). London: Sage. Lewis, A. (2010). Silence in the context of ‘child voice’. Children & Society, 24(1), 14-23. Lock, A. & Strong, T. (2010). Social Constructionism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lynch, K. & Lodge, A. (2002). Equality and Power in Schools. London: Routledge Falmer. Mackay, N. (2003). Psychotherapy and the idea of meaning. Theory & Psychology, 13(3), 359-386. MacMahon B., Pugh, T. F. & Ipsen, J. (1960). Epidemiologic Methods. Boston: Little Brown & Co. Maddux, J. (2011). Stopping the “madness”: Positive psychology and deconstructing the illness ideology and the DSM. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (2nd Eds.), the Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 610-70). New York: Oxford Press. Mc Guckin, C., & Minton, S. (in press). From theory to practice: Two ecosystemic approaches and their applications to understanding school bullying. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling. McDonnell, P. (2003). Developments in special education in Ireland: Deep structures and policy making. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 7(3), 259-269. McIntyre, R. & Hennessy, E. (2011, April). Seeking Multiple Perspectives: A qualitative investigation of ADHD in Ireland. Poster presented at Society for Research in Child Development, Montreal. Munn, P. & Lloyd, G. (2005). Exclusion and excluded pupils. British Educational Research Journal, 31(2), 205-221. National Children’s Strategy (2000). Our Children - Their Lives. Dublin: Stationery Office. National Council for Special Education (NCSE) (2006). Implementation Report: Plan for the phased implementation of the EPSEN Act 2004. Ireland: NCSE. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Clinical Guidelines. UK: NICE. Neimeyer, R. A. & Raskin, J. D. (2000). Constructions of Disorder: Meaning-making frameworks for psychotherapy (pp. 15-40). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Norwich, B. (2008). Dilemmas of Difference, Inclusion and Disability. London: Routledge. Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Frontiers of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. O’Driscoll, C., Heary, C., Hennessy, E., & McKeague, L. (2010). Explicit and implicit stigma towards peers with mental health problems in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 53(10), 1054–1062. Oliver, M. (2000). Why do insider perspectives matter? In M. Moore (Eds.), Insider Perspectives on Inclusion: Raising Voices, Raising Issues (pp. 7 –17). Sheffield: Philip Armstrong. Osler, A. (2006). Excluded girls: Interpersonal, institutional and structural violence in schooling. Gender & Education, 18(6), 571-589. Paris, M. E. & Epting, F.(2004). Social and personal construction: Two sides of the same coin. In J. R. Raskin & S. K. Bridges (Eds.), Studies in Meaning 2: Bridging the personal and social in constructivist psychology (pp. 3-35). New York: Pace University Press. Park, C.L. & Folkman, S. (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1(2), 115-144. Pearlin, L. I. & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2-21. Polanczyk G., de Lima M. S., Horta, B. L., Biederman, J., & Rohde, L. A. (2007). The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 942–948. Punch, S. (2002). Interviewing strategies with young people: The ‘secret box’, stimulus material and task-based activities. Children and Society, 16, 45–56. Raskin, J. D. (2002). Constructivism in psychology: Personal construct psychology, radical constructivism, and social constructionism. In J. D. Raskin & S. K. Bridges (Eds.), Studies in Meaning: Exploring Constructivist Psychology (pp. 1-25). New York: Pace University Press. Reeves, D. (2012). Psycho-emotional disablism in the lives of people experiencing mental distress. In J. Anderson, B. Sapey, & H. Spandler (Eds.), Distress or Disability? (pp. 30-32). Lancaster: Lancaster University. Robinson, C. & Taylor, C. (2007). Theorizing student voice: Values and perspectives. Improving Schools, 10(1), 5-17. Robinson, J. & Fielding, M. (2006). Student voice and the perils of popularity. Educational Review, 58(2), 219-231. Roger, C. (1951). Client-Centred Therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. London: Constable. Rose, R. & Shevlin, M. (2004). Encouraging voices: Listening to young people who have been marginalised. Support for Learning, 19(4), 155-161. Rudduck, J. & Flutter, J. (2003). How To Improve Your School: Giving pupils a voice. London: Continuum Press. Sexton, T. L. (1997). Constructivist thinking within the history of ideas: The challenge of a new paradigm. In T. L. Sexton & B. L. Griffin (Eds.), Constructivist Thinking in Counseling Practice, Research, and Training (pp. 3-18). New York: Teachers College Press. Shah, P. & Mountain, D. (2007). The medical model is dead – long live the medical model. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 375–377. Shakespeare, T., & Watson, N. (1997). Defending the social model. Disability & Society, 12(2), 293–300. Sharry, J. (2004). Counselling Children, Adolescents, and Families: A Strength-Based Approach. London: Sage. Shevlin, M. & Rose, R. (2008). Pupils as partners in education decision-making: Responding to the legislation in England and Ireland. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23. Singh, I. (2007). Capacity and competence in children as research participants. EMBO, 8(1), 35-39. Singh, I. (2011). A disorder of anger and aggression: Children’s perspectives on attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the UK. Social Science & Medicine, 73, 889-896. Singh, I. (2012). VOICES Study: Final Report. London, UK. Special Education Support Services (2012). SEN Categories: Categories of Special Educational Need – Teaching and Learning. Ireland: SESS. Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), the Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd Eds.: pp. 443-466). California: Sage. Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: Norton. Tangen, R. (2009). Conceptualising Quality of School Life from Pupils’ Perspective: A four dimensional model. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(8), 829-844. Taylor, C. & Robinson, C. (2009). Student voice: theorising power and participation. Pedagogy, Culture, & Society, 17(2), 161-175. Taylor, E. (2009). Developing ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiarty, 50(1-2), 126-132. Thomas, G. & Loxley, A. (2005). Discourses on Bad Children and Bad Schools. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(2), 175-182. Thomas, G. (2009). An epistemology for inclusion. In P. Hick, R. Kershner, & P. T. Farrell (Eds.), Psychology for Inclusive Education (pp. 13-23). New York: Routledge. Thomas, W. I. & Thomas, D. S. (1928). The Child in America: Behavior problems and programs. New York: Knopf. Thomson, P. (2008). Children and young people: Voices in visual research. In P. Thomson (Eds.), Doing Visual Research with Children and Young People (pp. 1-19). London: Routledge. Thomson, P. (2011). Coming to terms with ‘voice’. In G. Czerniawski & W. Kidd (Eds.), the Student Voice Handbook: Bridging the Academic/Practitioner Divide (pp. 19-30). UK: Emerald Group. Tomasini, F. (2012). Disability ‘and’ distress: Towards understanding the vulnerable bodysubject. In J. Anderson, B. Sapey, & H. Spandler (Eds.), Distress or Disability? (pp. 24-29). Lancaster: Lancaster University. Toynbee, F. (2009). The perspectives of young people with SEBD about educational provision. In C. Cefi & P. Cooper (Eds.), Promoting Emotional Education (pp. 27-36). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Travell, C. L. (2005). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Experiences and Perspectives of Young People and their Parents. Doctoral Thesis, the University of Birmingham. UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Geneva: UN. Watermeyer, B. (2012). Is it possible to create a politically engaged, contextual psychology of disability? Disability & Society, 27(2), 161-174. Watts, A. (1951). The Wisdom of Insecurity. New York: Vintage. Wearmouth, J. (1999). Another one flew over: Maladjusted Jack’s perceptions of his label. British Journal of Special Education 26(1), 15-22. Winkel, G., Saegert, S., & Evans, G. W. (2009). An ecological perspective on theory, methods, and analysis in environmental psychology: Advances and challenges. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 318–328. Wright, B. A. & Lopez, S. J. (2009). Widening the diagnostic focus: A case for including human strengths and environmental resources. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), the Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 26-44). New York: Oxford University Press.