Global Effects of domestic and Foreign Lobbying

advertisement

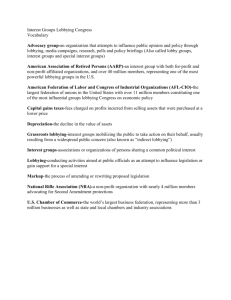

GLOBAL EFFECTS OF DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN LOBBYING 1 Abstract Though lobbying is seen as a staple in American democracy and the law making process, there is overwhelming evidence that lobbying is in fact not democratic at all. The purpose of this research is to expose the un-democratic tactics that lobbyists use to further corporate interest, not public interest. This Analysis aims at uncovering the corruption behind lobbying both in and outside the United States and show how truly unjust it is. Not only does this paper aim to uncover unjust lobbying, it’s also an attempt to explain how American lobbying has an effect on global economies and foreign affairs. The influence of American lobbying on a global scale is alarming and should be considered when analyzing American influence in foreign countries. Extensive analysis on foreign trade policies and resource privatization influenced by lobbying is used to support the claim that lobbying is used to control foreign affairs and profit multinational businesses. This research also presents the argument backed by political researchers that lobbying is not as influential as previously claimed through analysis of quantitative data, however empirical analysis of corporations’ return of investment from lobbying shows otherwise. In conclusion, this research intends to show the negative repercussions of lobbying on a global scale and how it only benefits the healthy, not the public. 2 Lobbying is engrained in American political history and is accepted as part of the law-making process. Lobbying is also found in other parts of the World, from England to Lithuania, to even a handful of Latin American countries such as Ecuador and Bolivia (though not as influential or regulated as American lobbying is). What many don’t know is that even domestic forms of lobbying has the power to change foreign relations and reshape the global economy, not just implement policy change within the lobbying country. Corporations have the financial advantage to gain an upper hand on policy changes geared towards their interest through lobbying methods that can change economies all over the world. Some argue that lobbying’s influential power on law and policy are not just fueled by funding but involve other factors. However, this essay is an attempt to show that money is in fact one of the most influential factors that go into successful lobbying. As a result, lobbying is not made to gear toward public interests even when NGOs use it as a political tactic. In the end, direct action is needed when change is necessary. The three countries that use lobbying the most as a means of law making and policy reform is the United States, England, and Australia (with other countries in the EU that use lobbying but is not as influential). Lobbying is a political tactic to gain influence over official decision-makers and various government representatives in order to push a particular interest group or corporation’s agenda through political and social “networking”. This “networking” can range from a lobbyist buying a round of golf for a legislator in order to talk about an up coming bill, to a union representative offering endorsement and campaign money to a representative if a certain policy is changed. In this context, international corporations spend an unbelievable amount of money in order GLOBAL EFFECTS OF DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN LOBBYING 3 to gain more profits. How successful is this tactic? Lets take a look at the numbers: oil companies invested $347 million in campaign donations and lobbying that ultimately lead to government subsidies of fossil fuel companies that led to a profit of $20 billion (that’s $59 profited for every $1 spent towards lobbying, a 5,900% return on investment), US corporations through the US Chamber of Commerce invested $283 million on lobbying for tax breaks in order to bring offshore profits back to American banks which led them to pay $63 billion less on taxes ( that’s $220 saved for every $1 spent, or 22,000% return on investment), and the pharmaceutical industry invested $116 million lobbying to keep federal health care like Medicare and Medicaid from haggling with cheaper competitive drug companies, keeping drug prices high and making a profit of $90 billion a year as a result (that’s $775 earned for every $1 spent, or 77,500% return on investment)(Alexander et al., 2009). This kind of influence is seen in all types of multinational corporations in order to keep profits up. As Susan George states on her analysis of the agribusiness and the advent of the Green Revolution, corporations exerted their financial might to influence policy makers to subsidize High Yield Varity crop growers and corporations, and even went so far as to patent the seeds themselves (George, 1989). These policies had negative effects not just on small farm owners in the US, but in countries all over the world including Mexico and India. Unfortunately, the agribusiness’ control on HYV crops is only one of many examples of American lobbying having global effects on the economy. American lobbying in Washington DC goes beyond the jurisdiction of the United States and is a way of exerting power and push agendas on foreign countries. In Heindl’s (2012) analysis of diaspora groups’ influence on American foreign affairs, he states “Not 4 surprisingly, groups with deep pockets like the American Ireland Fund, the Cuban American National Foundation and the Anti-Defamation League frequently lobbied US, homeland and foreign governments, and used a generally broader array of tactics, than those with medium or small budgets…this reinforces the popular notion that lobbying governments is an expensive proposition that many NGOs simply cannot afford to do on a regular basis” (pg. 478). Not only does this reiterate the notion that affluent interest groups have the most power in terms of lobbying techniques, but it also sheds light on the fact that affluent groups of any nation or country can have this fiscal power over law making to push their own agenda (i.e. the Cuban American National Foundation pushing to lift all Cuban Embargos, or the American Jewish Congress influencing the Department of Defense to increase military spending for Israel). These changes in foreign policy are implemented by domestic companies and through organizations like the World Trade Organization. As stated in Victor Menotti’s (2006) analysis of WTO regulation, multinational businesses lobby and network within the WTO in order to create trade regulations that disenfranchise local populations in order to create more profit for the corporations (pg. 67). This is not just an example of lobbying that effects foreign countries, but an example of how lobbying directly goes against the interests and civil rights of a foreign nation’s population. A more concrete example of WTO lobbying going against national interests is tobacco companies lobbying to enforce regulation on cigarette imports to Thailand under WTO agreements. In McKenzie and Collin’s (2012) study on the WTO’s influence in cigarette imports in Thailand, they explain how “the United States Cigarette Export Association’s specific remit was to lobby the US government for elimination of regional restrictions on imported tobacco products, and to GLOBAL EFFECTS OF DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN LOBBYING 5 insulate US manufacturers from domestic advertising bans and other tobacco control regulations once market access was achieved… Association lobbyists also claimed that access to markets in Southeast Asia would generate considerable income and lead to domestic job creation” (pg. 151). This reform on Thailand’s import policy on tobacco sales put almost every Thai tobacco farmer out of business because they were competing with WTO-backed American cigarette companies. Not only did these policy reforms go against the need and want of the people of Thailand and their economy, but also went against the advice of health advocates, such as the World Health Organization, that domestic exports of cigarettes to Thailand would increase smoking habits in the nation and cause increased health risks (McKenzie & Collin, 2012, pg. 155). From Thailand to Israel, these cases show that American lobbying is proven to be influential in foreign policy making. Many political scientists and researchers would argue that the success rate of lobbying is not dependent on the amount of money spent, some even argue that lobbying is not as influential as most make it out to be. In McKay’s (2012) research on lobbying success in America, he claims “financial resources are not predictive of actual success in the policymaking process. Members of Congress will not keep their jobs if their constituents are dissatisfied, no matter how many campaign dollars interest groups give them nor how much time they spend with lobbyists… evidence suggests that some traits specific to the lobbyist, to the organization, and to the issue are associated with both greater organizational wealth and greater success.” (pg. 910). Although this research suggests that its not the amount of money funded for lobbying but the tactics of the lobbyists that make favorable policy changes, one can argue that wealthier 6 businesses (ie. global corporations) can afford to hire that best and most influential lobbyists money can buy which in turn makes them more successful. In Bernhagen’s (2012) research on lobbying in British Parliament, he claims that “organized interests rarely succeed in interfering with the promulgated plans of democratically elected policy makers… in only a small number of cases can lobbyists successfully persuade policy makers to take a course of action that is beneficial to the lobbyist while contravening the declared policy goals of a democratically mandated policy maker” (pg. 36). This research proposes that lobbyist have incentives to keep their jobs and represent the interests of the people, not matter what country they represent (America, England, or others). However, there has been plenty of instances where policy changes were made against citizens’ wishes. Take for example the recent proposal for a change in education policy: California legislators voted down a bill that would make firing teachers who committed crimes related to sex, drugs, or violence against students easier. This bill was written after a California teacher was accused of sexual assaulting his students and was given $40,000 to resign verses the yearlong process required to actually fire him. The majority of those who choose not to vote, which led to the bill’s down fall, were representatives that received campaign money from the American Federation of Teachers. In non-American policy and law making reforms, lobbying can be used by grassroots campaigns to bring the voice back to the people. In the US there are leaders for Social Justice like the Human Rights Campaign that lobbies for gay rights, but in Ecuador political tactics such as lobbying was used to de-privatize water. Hoogesteger’s (2012) research on the Interjuntas-Chimborazo Water Federation’s GLOBAL EFFECTS OF DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN LOBBYING 7 regulation on water in Ecuador highlights the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of lobbying to keep public interests in mind. In his research, Hoogesteger explains how “the Legal Advisory Office established a dossier to document the injustices and problems that water users experienced. With the dossier, Interjuntas-Chimborazo started a lobbying process at provincial and national levels to replace the director of the [national] Water Agency. For this, a legal process was started… but the process stopped and the head of the WA office reinstalled”(pg 82). Because of the lack of funding that the Interjuntas-Chimborazo council had, their lobbying efforts went unnoticed, as a result, “On June 27 a massive mobilization of more than 4,000 water users was organized in the city of Riobamba. The mobilization ended with an 18 day occupation of the WA office. The water users remained in the offices until their demands were heard and several agreements reached. The agreements included the dismissal of the head and the secretary of the WA office and the establishment of a transparent, open public procedure to establish a new director. This procedure was carefully supervised by Interjuntas-Chimborazo. In January 2006, a new director was chosen and the WA office became more transparent and just77” (Hoogesteger, 2012, pg. 83). This case study shows that lobbying is only successful for affluent interest groups, making lobbying virtually useless for NGO interests groups, like that of the Interjuntas-Chimborazo federation in Ecuador. This is not just a lobbying problem in Latin America but in the United States as well. Social Justice Groups like the Human Rights Campaign mentioned before invest only a fraction into lobbying compared to what multinationals invest. As a result it is overwhelming apparent 8 that the more money you have towards funding lobbyists the more successful you are in implementing policy changes that benefit your interests. So what about interest groups that don’t have this funding? What about grassroots organizations that fight against the social inequalities that result from corporate lobbying? Just like we saw in the case study in Ecuador, lobbying just wasn’t enough. Protesting and direct action was truly needed in order to push the interest of the common people, or in other words, protesting in large numbers truly shows the legitimacy of an organization, not the amount of money you can invest in lobbying. Though there is hope for disenfranchised people through protesting and direct action, NGO’s are still the Davids against Big Business Goliaths, but unfortunately rocks have been privatized and slings are too expensive. GLOBAL EFFECTS OF DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN LOBBYING 9 Sources Cited Alexander, R., Mazza, S. W., & Scholz, S. (2009). Measuring rates of return for lobbying expenditures: an empirical analysis under the American Jobs Creation Act. Unpublished working paper. University of Kansas. George, S. (1989).Chapter 5: The Green Revolution, How the Other Half Dies (pages 88107). Hamondsworth: Penguin Books. Heindl, B. S. (2012). Transnational activism in ethnic diasporas: Insights from cuban exiles, american jews and irish americans.Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(3), 463-482. Mander, J. (2006) Menotti, Chapter 7: How the World Trade Organization Diminishes Native Sovereignty. Paradigm wars: Indigenous peoples' resistance to globalization (pages 59 – 68) . Sierra Club Books. MacKenzie, R., & Collin, J. (2012). ‘Trade policy, not morals or health policy’: The US Trade Representative, tobacco companies and market liberalization in Thailand. Global Social Policy, 12(2), 149-172. McKay, A. (2012). Buying policy? The effects of lobbyists' resources on their policy Success. Political Research Quarterly, 65(4), 908-923. 10 Bernhagen, P. (2012). When do politicians listen to lobbyists (and who benefits when they do)? European Journal of Political Research, 52(1), 20-43. Hoogesteger, J. (2012). Democratizing water governance from the grassroots: The development of interjuntas-chimborazo in the ecuadorian andes. Human Organization, 71(1), 76-86.