Reviewing research literature

advertisement

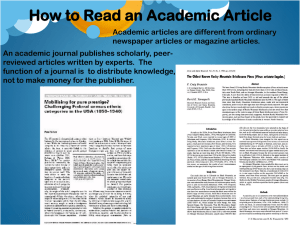

Literature Review How not to reinvent the wheel Types of literature reviews • A brief review of existing knowledge in an area as it relates to your topic of study. It is organized as an argument in favor of a given research study, explaining why it should be undertaken and how it will contribute to our knowledge on a given topic • A reader should come to the conclusion that your proposed research will shed light on an important topic/concern. Types of literature reviews • A second type of literature review sees the review as an end in itself. It is an extensive discussion of a topic that attempts to critique and integrate a large body of literature in a way that reveals areas of agreement, disagreement, and missing information. It usually encourages the reader to adopt a particulary theoretical perspective. Literature review • Consists of: • A search for information regarding the chosen topic • Quality of information • Quantity of information • A thoughtful analysis of the content identified in the first step • Organization • An essay written based on that analysis • The steps overlap How do you approach a literature review? 1. Develop a general understanding of the topic 1. Identify major theories, research streams 2. Identify subject terms and important language relating to your topic 3. Search library catalogs and databases for quality information on the topic 4. Supplement scholarly information with news and popular culture sources 5. Organize the material for presentation 6. Write the review, edit, rewrite, edit again, etc. until the final piece is well-written, succinct and compelling Important information to make your life easier: • You can download a citation manager/database software program from UK for free • Endnote X2 for your appropriate operating system • http://download.uky.edu/ General sources: Encyclopedias • General v. topical Handbooks • Somewhat more hit-and-miss than an encyclopedia • However, articles tend to be more in-depth and to cover research better Consider a textbook • Textbooks on the topic area can be useful as well Yearbooks, annual reviews Take-away from general sources • A basic understanding of the topic of interest • A set of sources for further, more indepth reading Books • Range from popular books aimed at a general audience to scholarly books that are advanced and demanding • Abstracts and book reviews help you determine whether a book is too general or too advanced and demanding for your needs Search library catalogs and databases for quality information on the topic • Go to the Library web page • Choose either • Or Identify subject terms, important language of the field or study topic • Examine the library catalog entries for subject terms that relate to those books and articles that you find most useful • Keep a list of terms for use in searches • Write down important terms from abstracts, headings and subheadings in your reading For books • Search the catalog • Scholarly books on a topic are: • most likely to provide a comprehensive treatment of your topic • most likely to develop a fully laid-out theoretical argument • often out of date compared to articles • not subject to the type of peer review that articles are Edited books • Some books are a compilation of reviews of important topics within a larger subject area • Chapters are written by experts on particular topics and are reviewed by the editors of the volume to see that they meet high standards For articles • Go to the database page • Find an appropriate database to search for articles • I usually pick resources organized by subject and then scroll to “Communications” and hit “submit” • “Communication and Mass Media Complete” • This database provides citations from a great number of media-related journals, usually with a short abstract. You can download full-text (pdf) files from several of the periodicals. For articles • You can search using the subject terms you kept from the earlier citations • Limit your searches around the terms to try to find the best sources first • You can limit the search to scholarly (peerreviewed) and/or full-text articles • Expand if you don’t get enough cites at first For articles • Boolean logic • “And” v. “or” v. “not” • Use of selected fields • Some fields are quite restrictive (‘title’) while others not at all restrictive (‘all text’) An example: “Cultivation” Type “cultivation” in blank and require that it be included in the abstract • or • “authority” in all text and “television” in abstract For articles • You could also find one or more of the articles cited in the overall reviews you looked at earlier • Then use the subject terms for the best articles • Or else look for the authors of the overall reviews and see what they have written For articles • When you have found some good articles and are reading them, you should be able to identify sources the authors used that would help your review • Carry on a “fan-out” search—look up the sources from the bibliographies of the best articles • In several of the databases you can electronically link to cited sources and can even save full-text versions of those articles Reviews in academic journals • Some journals will carry review articles or overviews of a topic area • Use “review” or “overview” as a search term in an appropriate database along with topic-specific terms • Holmstrom, A. J. (2004). The effects of the media on body image: A metaanalysis. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48, 196-217. Don’t be skimpy When you are starting out it’s easier to collect too much and shed what’s unnecessary than to have to make multiple searches As the literature review progresses and you know what you need, you can more narrowly tailor the follow-up searches and keep only the best content for use in the review Supplement scholarly information with news and popular culture sources • Though they generally are not as well thought-out or accurate, popular sources can provide examples, interesting angles and/or update your findings from the academic literature • Websites of organizations involved with your topic (may do their own research, develop white papers, etc.) • Pew Center • Newspaper/newsmagazine sites are available with helpful (and easily readable) stories about many topics of interest • Library databases provide many full-text newspapers and popular magazines NOTE: Go to news, popular magazine, or WWW sources AFTER you have done a good job mining the scholarly literature. You’ll be more efficient that way, and will be able to critique the sources you find more effectively. Admittedly, some of the most recent or technical topics may call for more use of news and popular culture Organize the material for presentation • Develop an outline!! (And then follow it). • Don’t do the “train of consciousness” thing. What seems perfectly rational and sensible to you will turn out to be full of logical holes, leaps of faith and selfcontradictory logic. Writing the review • Lay out your argument in step-by-step fashion and then place the evidence you have found where it fits on the outline. • Do some of your claims lack support? • Are some arguments especially controversial? • These require the most background Write the review, edit, rewrite, edit again, etc. until the final piece is organized, succinct and compelling • Presentation counts! Spelling, usage, structure, organization—they all matter in how well your ideas are presented. You are trying to convince the reader of something. A well-written, articulate argument is more convincing. NOTE: • One of the most common shortcomings of research studies is that the researcher does not write a good literature review. Putting in the effort during the conceptualization stage will be rewarded during operationalization and interpretation. Your write-up will be faster and higher quality.