Timeline of the American Revolution

advertisement

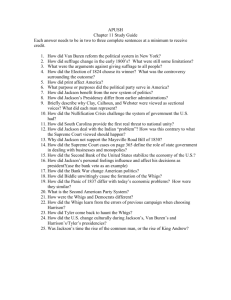

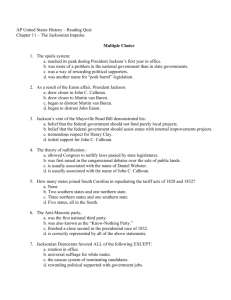

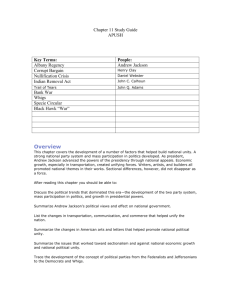

Chapter 13 Notes Andrew Jackson, Trail of Tears, Whigs, Texas Andrew Jackson Andrew Jackson 1767-1845 • Seventh president of the United States. • Created what is known as the Modern Democratic Party • A forceful, at times violent personality, Jackson continues to provoke controversy among historians, who see in him reflections of both the best and the worst tendencies of the new Republic. • Jackson was a southwestern gentleman who combined a sense of rough-hewn egalitarianism with the gentlemanly honor typical of his class. • Born in the Carolina backwoods to an immigrant farming family from Ireland, he fought in the Revolution and was captured and imprisoned by the British. • By war's end, all but one member of his immediate family had died in connection with the conflict. • A teenager alone and adrift, Jackson eventually decided to study law and then to head farther west. • Although immensely ambitious, he would never lose touch with his plebeian roots. Election of 1824 Corrupt Bargain? • The Republican party broke apart in the 1824 election. • A large majority of the states now chose electors by popular vote, and the people's vote was considered sufficiently important to record. • With four candidates, none received a majority. Jackson received 99 electoral votes with 152,901 popular votes (42.34 percent); Adams, 84 electoral votes with 114,023 popular votes (31.57 percent); Crawford, 41 electoral votes and 47,217 popular votes (13.08 percent); and Clay, 37 electoral votes and 46,979 popular votes (13.01 percent). • The choice of president therefore fell to the House of Representatives. • Many politicians assumed that House Speaker Henry Clay had the power to choose the next president but not to elect himself. • Clay threw his support to Adams, who was then elected. When Adams subsequently named Clay secretary of state, the Jacksonians charged that the two men had made a "corrupt bargain." • John C. Calhoun was chosen vice president by the electoral college with a majority of 182 votes. The Presidency… • Jackson defeated Adams in 1828, believing he had vindicated his principle that "the majority is to govern." • He checked the program of federal internal improvements proffered by Adams and Clay, believing it a dangerous expansion of federal power favorable to established wealth. • On Indian affairs, he ran roughshod over his critics and proclaimed a policy of forced relocation of eastern tribes west of the Mississippi River, opening fresh lands for settlers. • As antislavery agitation mounted—a danger, he thought, to national tranquility and his own democratic political project—he condemned the abolitionists and backed efforts to curtail their activities. • At the same time, he angrily defeated those emerging southern nationalists (led by his former ally, John C. Calhoun) who defied federal authority in the name of states' rights. Cherokee Nation v. Georgia 1831 • • • • • • • • • By refusing to consider Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Supreme Court denied self-government to a Native American tribe. Prior to 1831, the federal government treated tribes as foreign entities in conducting official interactions with them. In an effort to keep their tribal lands, the Cherokee living within Georgia turned to farming and ranching. They also wrote a constitution and laws reflecting some aspects of U.S. law. The state of Georgia declared all the Cherokee laws void, prompting that nation to appeal to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote the opinion dismissing the case, saying that Indian tribes were "domestic dependent nations" and could not turn to the Supreme Court. The case's dismissal allowed Georgia to strip the tribe of its governmental forms. A year later, however, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Marshall wrote that the "laws of Georgia can have no force" in Cherokee territory. He then established the doctrine that the national government alone could conduct Native American affairs. President Andrew Jackson and John Marshall locked horns on the issue. After Worcester, Jackson remarked, "John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it." Georgia instead enforced its laws on the Cherokee tribe. Trail of Tears Five Civilized Tribes • The term Trail of Tears refers to the removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from their ancient homeland in the East to present-day Oklahoma. • Though all of the tribes—Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles—were forcibly uprooted and herded westward, the removals varied in severity. The Cherokee • In 1791, a U.S. treaty had recognized Cherokee territory in Georgia as independent, and the Cherokee people had created a thriving republic with a written constitution. • For decades, the state of Georgia sought to enforce its authority over the Cherokee Nation, but its efforts had little effect until the election of President Andrew Jackson, a longtime supporter of Indian removal. • Although the Supreme Court declared Congress's 1830 Indian removal bill unconstitutional (Worcester v. Georgia, 1832), the national and state harassment continued, culminating in the rounding up of the Cherokee by troops in 1838. • President Andrew Jackson ordered their removal under the terms of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, intended to provide more land for white settlement. What happened? • Under the supervision of Gen. Winfield Scott, the U.S. Army uprooted thousands of Indians from their homes, stripped them of their possessions, and herded them west on foot. • The Cherokee were forced to abandon their property, livestock, and ancestral burial grounds and move to camps in Tennessee. • From there, in the midst of severe winter weather, they were marched another eight hundred miles to Indian Territory. • An estimated four thousand people—over 25 percent of the Cherokee Nation—died during the march. • The Trail of Tears, the path the Cherokee followed, became a national monument in 1987, serving as a symbol of the wrongs suffered by Indians at the hands of the U.S. government The Kitchen Cabinet • The "Kitchen Cabinet" was a group of unofficial advisers with whom President Andrew Jackson regularly consulted, particularly during his first years in office, 1829 to 1831. • Jackson soon stopped holding cabinet meetings altogether and instead formed his Kitchen Cabinet. • Only two members of the official cabinet joined the informal group: Martin Van Buren and the secretary of war, John H. Eaton. • Relations between Jackson and his official cabinet reached a new low in the spring of 1831, when all the members except Van Buren opposed the president and supported their wives in ostracizing Secretary Eaton's new wife, a former barmaid. • Eaton and Van Buren chose to resign over the matter, permitting Jackson to request resignations from the rest of the cabinet, most of whom were Calhoun supporters. • After the formation of a wholly new cabinet in the summer of 1831, the role of the Kitchen Cabinet was considerably diminished. Nullification • The famous nullification confrontation of 1832-1833, pitting President Andrew Jackson against South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun over whether a state could nullify federal law, was an important step in a long series of attempts to define the proper powers of the states. • In 1832-1833, Calhoun and his fellow nullifiers also threatened to secede if the federal agency trampled on states' rights. • But the nullifiers added the notion that a state convention, while remaining in the Union, could use its absolute sovereignty to render a law of the federal agency null and void within that particular state's limits. • The occasion for this addition to states' rights politics was an escalation of anxiety within the South's most extreme state, South Carolina. Tricky Tariffs • The simultaneous passage of progressively higher American tariffs in 1816, 1824, and 1828 to protect American industry from more advanced European competitors at least temporarily boosted the prices American farmers had to pay for industrial products. • Carolina cotton producers blamed all their woes on these tariffs. They also claimed that the federal agency could not use its power to pass tariffs, a constitutionally enumerated, revenue-enhancing act, in order to protect industry, a manufacture-enhancing act nowhere explicitly authorized in the Constitution. • In 1832, a Carolina convention declared the tariff null and void in the state and warned it would secede if President Andrew Jackson tried to enforce the tariff in South Carolina. • Behind the explicit assault on the tariff lay another implicit concern—protecting slavery. • The first confrontation over slavery, which led to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, had helped inspire the unsuccessful slave revolt in Charleston led by Denmark Vesey in 1822. • Southerners outside of South Carolina, though they also suffered from low cotton prices and disliked high tariffs, did not have the nullifiers' angry edge, partly because cotton yields were not as poor on virgin southwestern soil, partly because their fears of an imminent challenge to slavery were less acute since their region had fewer blacks. • These less distressed southerners clung to Jefferson's old position that states' rights allowed a state to secede. But they rejected Calhoun's addendum that a state could remain under a general government and still nullify its laws. • • • • • President Jackson pleased the anti-nullification southern majority by urging lower tariffs. But he angered many of his southern states' rights followers by denouncing not only Calhoun's addendum but also the essence of Jefferson and Madison's original position. Jackson's notion that states' rights justified neither state nullification nor state secession, stated most powerfully in his Nullification Proclamation of December 10, 1832, precipitated the defection of a fraction of his states' rights followers over to the opposition, which became the Whig party. Until 1832, Jackson had possessed almost monopoly control of the Deep South. Now a two-party struggle swept over the region, with both parties claiming that they could save states' rights and slavery. Antebellum southerners would never try to nullify another law, although the nullification controversy would reecho in the George Wallace-led "interpositions" of southern states against federal desegregation edicts in the 1960s. Instead, in the pre-Civil War years, most southerners worked within the two-party system to shore up slavery and states' rights. For many years, southern two-party politicians succeeded in this enterprise. The Bank… • After vetoing the Bank's re-charter in 1832—a move that helped secure his reelection—he ordered the removal of U.S. funds, tried to put the nation's economy on a hard-money footing, and revived populist, anti-capitalist sentiments latent since Thomas Jefferson's presidency. • After seeing his protégé Martin Van Buren elected as his successor, he returned to the Hermitage, where he lived out his final years as a country gentleman and elder statesman. The Hermitage Anti Masonic Party • • • • • • • The Anti-Masonic party, the first third-party movement in the United States, arose in response to the disappearance of William Morgan, shortly after his release on September 12, 1826, from a Canandaigua, New York, jail. Morgan had threatened to publish a book divulging the secrets of Freemasonry; opponents of the order asserted that a conspiracy among Masons had led to his arrest on trumped-up charges and subsequently to his being kidnapped and murdered. The Anti-Masonic movement grew rapidly, drawing its initial following from farmers and skilled craftsmen—many of them with ties to evangelicalism and the temperance movement. They maintained that the Masonic order's secrecy, rituals, and aristocratic character posed a threat to republican democracy. In 1831, the Anti-Masonic party nominated William Wirt to run for president; in the process, it became the first American political party to select a presidential candidate by means of a national convention and the first to adopt an official party platform. Wirt carried only one state (Vermont) in 1832, but the party continued to grow, offering an increasingly general program of reform. As it expanded, it came to be dominated by new members more impelled by personal ambition or by a general opposition to the Jacksonian Democrats than by Anti-Masonry. At its second and final convention (1835), the Anti-Masonic party approved a slate for 1836 identical to that of the new Whig party, and thereafter it disappeared into the Whig coalition. The Whig Party • In 1834 political opponents of President Andrew Jackson organized a new party to contest Jacksonian Democrats nationally and in the states. • Guided by their most prominent leader, Henry Clay, they called themselves Whigs—the name of the English antimonarchist party— the better to stigmatize the seventh president as "King Andrew." • They were immediately derided by the Jacksonian Democrats as a party devoted to the interests of wealth and aristocracy, a charge they were never able to shake completely.. • Although unable to unite behind a single candidate in 1836, thus permitting Jackson's handpicked successor Martin Van Buren to obtain an electoral majority, the Whigs won a popular vote for their candidates that was close to the popular tally for the Democrats. And in 1840 and 1848, the party captured the White House. • Their only loss in a presidential election during the decade occurred in 1844 when Clay lost by a hair to the Democrats' dark horse James K. Polk, who had greater appeal to voters favoring the expansion both of territory and slavery. • But in 1852, as slavery's expansion became the great issue of American politics, the Whigs suffered a drastic decline in popularity. Who are they? • Historians have interpreted the Whigs in strikingly different ways. They have been seen as champions of banks, business, corporations, economic growth, the positive liberal state, humanitarian reform, and morality in politics, and as opponents of expansionism, executive tyranny, states' rights, labor, and the democratic suffrage, among other things. • The Whig party was founded by individuals united only in their antagonism to Jackson's war on the Second Bank of the United States and his high-handed measures in waging that war and ignoring Supreme Court decisions, the Constitution, and Indian rights embodied in federal treaties. • Beyond that, however, there were Whigs and Whigs. Some played the demagogic anti-Catholic game; others scorned it. Some spoke critically of working people; others, admiringly. Detailed studies of the Whig party in the states and biographies of such Whig leaders as Clay, William Seward, Daniel Webster, and Horace Greeley reveal dissimilar policies from one state to another and important differences in the character, beliefs, and actions of the leaders. Who Supported the Whigs? • In Congress, Whigs supported the Second Bank of the United States, a high tariff, distribution of land revenues to the states, relief legislation to mitigate the effects of the great depression that followed the financial panics of 1837 and 1839, and federal reapportionment of House seats (a "reform" likely to enlarge Whig representation in Congress). • Studies of voting patterns in the states reveal Whig support of banks, limited liability for corporations, prison reform, educational reform, abolition of capital punishment, and temperance. • Although the Whig party was hardly an antislavery party, free blacks and abolitionists overwhelmingly preferred it to more ardently proslavery Jacksonian Democrats. • Whigs fared well at the polls among people of all classes in economically dynamic communities heavily engaged in commerce. • Jacksonian propaganda did induce many people to regard the Whigs as an upper-class party (not organized working men, however, whose leaders dismissed both Democrats and Whigs as "humbugs"). Their Demise • Ultimately, however, the Whigs are best understood as an American major party trying to be many things to many men, ready to abandon one deeply held "conviction" for another in the drive for political power. • The party died not because its unique aura no longer appealed to voters but because it could not cope effectively or persuasively with what after the Compromise of 1850 became the great issue of American politics, the expansion of slavery. The Texas Revolution and Alamo The Beginning… • • • • • • • After gaining independence from Spain in the 1820s, Mexico welcomed foreign settlers to sparsely populated Texas. Promised land on generous terms, some twenty thousand to twenty-five thousand Americans migrated there within a decade, far outnumbering the resident Mexicans (Tejanos). These immigrants clustered in relatively autonomous colonies along the lower Brazos and Colorado rivers and in the east. Alarmed at their reluctance to assimilate, Mexico passed laws in 1830 to slow American immigration. But with conflict between federalists and conservative centralists, the government could not enforce them. The regulations succeeded only in angering both settlers and those Tejanos interested in economic development. Some immigrants had never been reconciled to Mexican rule, citing putative U.S. claims to Texas by virtue of the Louisiana Purchase. Speculators counted on American annexation to raise the value of their land. Many Texans balked when earlier privileges, such as exemption from import duties, began to be withdrawn. Slavery in Texas • The national government and the state government of Coahuila and Texas (in which Texans had little influence) passed various emancipation measures and banned the import of American slaves. • Slaveholding Texans won exemption from some of these laws and evaded the others, and by 1835 slaves represented 10 to 15 percent of the non-Indian population. • Though the laws did little except slow the immigration of slaveholders, they clearly worried those who believed rich but labor-scarce Texas could prosper only through slave cultivation of staple crops. Civil Rights • The Mexican government presumed it could mold economic, social, even religious life in Texas. • It allowed the military to intrude upon what Americans took to be civil affairs—trade, legal proceedings, the master-slave relationship. • Yet this same government could not with any regularity provide such seeming fundamentals as speedy justice or trial by jury. • Immigrants from Jacksonian America had certain expectations of republican government, expectations that involved government neither claiming so much nor delivering so little. • This failure of government to behave in accustomed ways provoked a crisis in 1835. Politics • Political turmoil allowed Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna to amass an increasingly authoritarian power. • Like colonists in pre-revolutionary America, Texans perceived in the prospect of more strictly governed relations with the central government larger threats to their liberties and property. • A "war party" had been agitating for separation for some time, but the insistence of Mexican authorities that troublemakers be turned over to the military and, finally, an influx of Mexican troops in September convinced even the traditionally conciliatory Stephen Austin that "war is our only resource." War • • • • • • • • • A chaotic rebellion ensued. Significant military action occurred well before the rebels officially declared for independence. A provisional government, established in November, called only for separate statehood within Mexico and the federalist constitution of 1824, hoping to win the aid of liberal Mexicans elsewhere. That government could barely rally support within its own ranks, however, as the governor and council vied for authority. No single, effective military authority existed either. Volunteers held the Alamo, for instance, despite orders to the contrary. The creation of a new government and a consolidated military command after Texas declared independence in early March 1836 did not immediately bring order. The fall of the Alamo and the retreat of Sam Houston's forces eastward provoked panic and mass flight among civilians. Perhaps only the overconfidence this bred in Santa Anna—and the anger of Texan volunteers over the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad—saved the day. In late April, Houston's men surprised a Mexican force at San Jacinto. Houston's victory and the capture of Santa Anna suddenly ended Mexico's effort to subdue Texas. But apparently, independence was not what many Texans really desired. Voters elected Houston president, but also overwhelmingly endorsed union with the United States. Annexation of Texas? • The Jackson and Van Buren administrations spurned annexation, however. • They feared both diplomatic trouble and the political consequences of pressing for the admission of a territory in which slavery, now constitutionally protected, was growing rapidly. • Many southerners, eager to secure and expand America's slaveholding territory, worried that Britain intended to promote abolition in Texas. • President John Tyler vainly hoped that the Texas issue might win him a new following since he had alienated both parties. Texas a State • • • • • • • • • Democrat Martin Van Buren and Whig Henry Clay, announced against immediate annexation. A treaty admitting Texas as a territory failed to win a majority in the Senate, much less the required two-thirds. But southern Democrats blocked Van Buren's nomination, opening the way for dark horse James Polk who campaigned for the acquisition of both Texas and Oregon (which presumably would remain free territory). Annexationists heralded Polk's narrow victory as a mandate. In early 1845 Congress, employing its power to admit new states, simply annexed Texas by a majority vote. Texan leaders who had been coy on annexation, hoping to prod either Europe into guaranteeing Texas independence or America into admitting Texas on the most favorable terms, likewise yielded to public sentiment. In June 1845 the republic's Congress accepted U.S. statehood. James Buchanan would later compare Texas to the Trojan horse. Its admission hastened the unraveling of the national parties. Annexation helped provoke war with Mexico, bringing America additional southwestern territory and fatally linking the politics of slavery and expansion.