ppt

advertisement

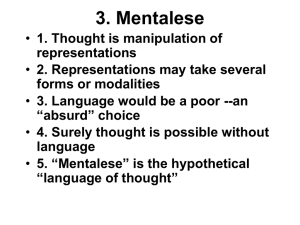

Modularity of Mind (Continued) & The Language of Thought Hypothesis Review Fodor’s Modularity Thesis Some functions of the brain are modular: e.g. Perception Language acquisition Language processing Some functions are not modular but controlled by a central processing system Mental modules are characterized as domain specific, fast, automatic, innate, inaccessible, informationally encapsulated and realized in a fixed neural architecture. Objections to modularity Modularity of mind is a very popular theory among cognitive scientists, but it is not universally accepted. Everyone accepts that the brain has specialized systems, e.g. the visual cortex. But are they modules? Do they fit Fodor’s criteria, e.g. informationally encapsulated, inaccessible, etc.? In “Is the Mind Really Modular” Jesse Prinz attacks each of Fodor’s criteria in turn, arguing that some modules may have some characteristics but Fodor’s criteria do not usefully describe dedicated systems of the brain. This article is available at: www.unc.edu/~prinz/PrinzModularity.pdf An alternative to modularity: brain areas have specializations, some innate and some acquired, but many areas can “moonlight” – contribute to more than one functional process, and there may be considerable communication between different functional systems. Some counter-evidence to modularity: 1) Plasticity of the brain. When one region of the brain is injured, another region can often take over its function (particularly in a very young brain). E.g. when a person becomes blind, the visual cortex can take over some of the functions of touch perception 2) Apparent communication between modules: i) sometimes knowing something affects your perception, if you are expecting to see a cat, you are more likely to see a hallucination of a cat. ii) watching someone’s lips while they speak can help you to hear their words more clearly. In fact, if you watch lips of someone speaking different words than you are hearing, your auditory input is systematically affected. The auditory module seems to receive input from the visual module. 2) Apparent communication between modules (cont.) iii) Conscious knowledge or effort can alter your visual perception, e.g. the duck-rabbit ambiguous figure: Amazingly, the duck-rabbit can be created in many different styles Three possibilities 1) The mind is not modular 2) Low-level systems are modular (e.g. perceptual systems), but higher-level systems are not modular (Fodor’s view) 3) The mind is massively modular How many modules? Fodor vs. massive modularity Massive modularity: • Promoted by Stephen Pinker • The mind is largely or entirely composed of modules. • The “central processing system” is also modular. Most cognitive scientists agree that the mind is modular, but there is much debate over exactly how many modules there are and how specific modules are. Stephen Pinker Mind ontologies with partonomies of modules Alignments are possible between various mind partonomies (often not separated from brain partonomies), starting from the ‘upper level’: Mind hasPart Sigmund Freud: Id Ego Super-Ego alignment Mind Stephen Pinker: Specialized Modules ... ... Central Processing System ... Modules that have been proposed: Approximate arithmetic Logic Folk physics Folk psychology -- “mind reading” Cheater detection Landscape preference Natural history Probabilistic judgment Etc. etc. etc. One controversial question: Is there a module for language acquisition (LAD – language acquisition device, as proposed by Noam Chomsky) or even some separate language of thought (LOT) as proposed by Jerry Fodor: http://host.uniroma3.it/progetti/kant/field/lot.html Mental Representations The number four is a concept. 4, 四 and IV are all graphic representations of the number four. “Four”, “si” and “quatro” are all spoken representations of the number four. We use linguistic representations of concepts when we speak or write. We also use other kinds of representations. Whether in language or image, symbols represent information. Computers also use symbols (e.g. 10010) to represent information Do our brains also use representations? If so, what kind? -- linguistic -- map -- pictorial Different types of representation for different uses • Visual system interprets input as image-like representations. • Somatosensory system generates body map. • What about intentional content? How is that represented in the brain? Intentional Mental Content Intentional = aboutness Intentional mental content is mental content that is about something. “I believe this is a pencil.” Statement about “this” and “pencil” and their relationship (denotative reference). Only representations have intentionality. A pencil is not about something. The word “pencil”, or a picture of a pencil are about something, i.e. they are about pencils. The representational theory of mind posits that all mental states are intentional. They are all about something. Beliefs, desires, hopes, fears, pain, perception, imagination, memory, even hallucinations, are all about something. (Imagination and hallucinations may be about something that doesn’t exist. Thus they may be about concepts or ideas rather than objects.) They are intentional mental states. How are intentional mental states represented in the brain? 貓 Thoughts represented as images No representation. Thoughts as brain states Thoughts as languagelike representations How are intentional mental states represented in the brain? (cont.) • One possibility: thoughts as images. • Problem: Too specific (“overspecification”) • Think: A person killed a tiger. • Image contains too much information: a man/woman/child shoots/poisons/strangles a large/small/orange/white tiger. Language of Thought Hypothesis Fodor’s proposal The Language of Thought Hypothesis (LOTH) Thinking takes place in a mental language, in which symbolic representations are manipulated in accordance to the rules of a combinatorial syntax (grammar). Language is composed of semantics and syntax. Individual words are semantic units – they refer to things (objects or concepts or ideas). These semantic units are combined together according to syntactical laws (grammar) to create propositions. E.g.: The horse is brown. Semantic units: horse, brown Syntax: the, is, word order Proposition: a statement about the color of the horse. LOTH proposes that thoughts are similarly constructed. Thus, thoughts, too, are constructed of individual semantic units connected with a combinatorial syntax. The language of thought need not be exactly the same as English, or any natural language, but it should have many of the same properties as natural languages have, and have the same expressive capabilities. An illustrative example: @ ^ ** # @ might mean “horse” ^ might indicate after a noun that a particular instance of the noun is under discussion ** might indicate that the noun preceding this symbol has the property indicated by the adjective following this symbol # might mean “brown” In logic, ** may become a binary predicate: **( @ ^ , # ) In Grailog, ** becomes an arc label: @^ ** # Or, expanded with node boundary lines: @^ ** # In the brain, of course, what is indicated as @ ^ ** and # would actually be represented as configurations of neurons. As in the example above, a language of thought need not have a grammar exactly like any natural language, but it should share characteristics that are common to all natural languages. Thus, it is possible to represent common nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc. of natural languages in the language of thought, and the grammar of the language of thought should have roughly the same functions as grammars in natural languages have. How are symbols meaningful? Where does semantics come from? Three possibilities: 1) Meaning is use (Wittgenstein) 2) Causal theory of meaning A symbol is meaningful because it has been caused by the object it represents in the right way. For Fodor, mental symbols are meaningful because they have been caused through the process of evolution to truly represent things in the world. 3) The inferential theory of meaning A symbol is meaningful by virtue of the role it plays in thinking Reasons for LOTH 1) Semantic parallels between language and thought Truth value: • Some sentences and thoughts have truth values – • Indicative sentences/thoughts: The sky is blue. It is raining. Some sentences and thoughts don’t have truth values – Interrogative sentences (questions), imperative sentences (orders); e.g. Is it raining? Go to class! – Hopes, fears, desires; e.g. It shall not rain tonight. • Note: the sentence “I hope it shall not rain tonight” has a truth value, since it may be true or false that I hope it; but my hope “It shall not rain tonight” does not have a truth value. 2) Syntactic Parallels between language and thought • Systematicity. Both language and thought are systematic. There is a systematic relationship among thoughts/sentences. Because of combinatorial syntax, the form of a sentence is distinct from its meaning. As a result, if someone, in any language, can make a meaningful sentence with a certain form of syntax, they can also use the same syntactic form to make a new sentence with a different meaning. For example, anyone who can say: “the dog is under the bed”, can say “the bed is under the dog.” Likewise with thoughts. Anyone who can think, “flowers smell sweeter than fruits” can think, “fruits smell sweeter than flowers.” • Productivity Both language and thought is productive (generative): an infinite number of sentences or thoughts can be produced using combinatorial syntax. (Of course, there are practical limitations to the number and length of sentences/thoughts that anyone can produce). E.g. The cat sat on the mat. The black cat sat on the yellow mat. The black cat, which ate my sausage yesterday, sat on the old yellow mat that I inherited from my grandmother. There is no limit to how long and complicated I could make this sentence (or how many sentences I can create starting with “the cat…”.) Would LOT be a natural language or mentalese? Two possibilities: 1) The language of thought (LOT) is a natural language, e.g. English, Chinese, etc., and it is learned. 2) LOT is an innate mental language, mentalese. Learning a natural language is a process of translation: translating English, etc., into mentalese. Fodor’s view The language of thought (LOT) is not a natural language. LOT is mentalese and is universal and innate. All people (and, to some extent, higher animals) think in mentalese. Mentalese contains all basic concepts. Thus, all basic concepts are innate. All complex concepts are (ultimately) built up from basic concepts (intermediate complex concepts can be used). Example: The complex concept of “bull” can be composed of the basic concepts of “cow” and “male”. The concepts of “cow” and “male” are innate, and thus we have the innate capacity to understand the concept of “bull”. Learning the word “bull” just makes our thinking more efficient. Thus, according to Fodor, every normal human being that has ever existed has had the conceptual capacity to understand computers, quarks, communism, cancer, etc. Even prehistorical hunter-gatherers had these concepts (or the ability to form these concepts through the combination of their innate concepts). We do not learn new concepts, we just learn to put familiar innate concepts together into new combinations. Learning a natural language is learning to identify the words of the natural language with our innate concepts. Basic concepts in LOT can be seen as picture producers in Roger Schank’s conceptual dependency theory (CDT). For a detailed LOT/CDT alignment see Charles Dunlop: http://www.springerlink.com/content/m0347214863t3260/ Arguments for mentalese 1) Translatability of propositions The same proposition can be stated in different languages. “It is raining” and “下 雨 了” express exactly the same proposition. Therefore, the proposition does not depend on the words of the natural language. Thus, the proposition is encoded in our brains in mentalese. 2) Concept learning/language learning We cannot acquire the word for a concept without already having the concept (in mentalese). E.g. how does a child learn the word “bird”. You point to birds and say “bird”. But how does he figure out what is a bird and what isn’t? The hypothesis and test theory: he already has several concepts, e.g. flying things, brown things, etc. and guesses which one you mean, until he hits on the concept of “bird”, tests it out and confirms it. What is a “blaggort”? Try to learn it! Blaggort Blaggort Blaggort Not a blaggort Not a blaggort Not a blaggort Not a blaggort Blaggort You start with some hypotheses, e.g. man, woman, old, young, dark-haired, light-haired, wearing glasses, not wearing glasses. Then you test and confirm positive and negative examples. You are more likely to start with ideas like “man” or “woman” than to start with ideas like “left-facing”, against a light background, looking at the camera, etc. Ideas like “formally dressed”, “wearing a hat” and “wearing glasses” are somewhere in between. We test for concepts we already have and finally understand the new concept (“blaggort”) by conjoining two of the old concepts (“man” and “wearing glasses”). The new concept need not have an (artificial) name (“blaggort”): mentalese allows anonymous concepts. Both order-sorted logic and description logic (DL) permit such class intersection / concept conjunction, indicated by a ‘squared’ intersection symbol, : “man” “wearing glasses” (cf. http://dl.kr.org) In Grailog, intersection equivalently becomes a ‘blank node’ that is a subclass of both concepts and inherits from both (multiple inheritance): Man Wearing Glasses subClassOf What is a “bladdink”? Try to learn it! Not a bladdink Bladdink Not a bladdink Not a bladdink Bladdink Not a bladdink Not a bladdink Not a bladdink New concept (“bladdink”) disjoins two concepts (“wearing a bow tie” or “wearing a hat”). The new concept need not have a name: mentalese allows taking the anonymous union. In Grailog, union yields a ‘blank node’ that has both concepts as subclasses (cf. Taxonomic RuleML): subClassOf Wearing a Bow Tie Wearing a Hat What is a “blannuls”? Try to learn it! Not a blannuls Not a blannuls Not a blannuls Blannuls Blannuls Blannuls Not a blannuls Not a blannuls New concept (“blannuls”) negates a concept, i.e. takes complement (not “wearing glasses”). The new concept need not have a name: mentalese allows anonymous negation. In Grailog, complement becomes a ‘dashed node’ that contains the class to be negated: Wearing Glasses negation What is a “blakkuri”? Try to learn it! Not a blakkuri Not a blakkuri Not a blakkuri Not a blakkuri Blakkuri Blakkuri Not a blakkuri Not a blakkuri New concept (“blakkuri”) conjoins two negated concepts, i.e. two complemented concepts (not “man” and not “wearing glasses”). It uses anonymous negation and conjunction. In Grailog, intersection of complements is a composition of these earlier constructs: Man Wearing Glasses subClassOf negation What is a “blappenu”? Try to learn it! Not a blappenu Blappenu Not a blappenu Not a blappenu Not a blappenu Blappenu Blappenu Not a blappenu New concept (“blappenu”) conjoins a negated concept (not “wearing a hat”) and the disjunction of a concept (“wearing a bow tie”) with a negated concept (not “man”). In Grailog, the embedded disjunction becomes a complex anonymous concept: Wearing a Bow Tie Wearing a Hat Man subClassOf negation A child just learning to speak also starts with the assumption that some hypotheses are more likely than others. E.g. when you point to this: and say “niu”, a child is more likely to think that you are naming the concept of “bird”, than to think you are naming the concept of sparrow, or brown things, or things with small heads. When you say, “that’s the wind”, how does a child know what you’re referring to? He has to make a likely guess. He can do this because he already has the capacity to think about the wind (i.e. he already has a concept of wind). How does a child learn to understand and use the word “beautiful” correctly? Again, he must have a concept of beauty. Arguments for mentalese (cont.) 3) Ambiguity in natural language The word “bank” has two meanings. With the sentence “I’m going to the bank”, I can think two different thoughts: I’m going to the financial institution. I’m going to the river’s edge. going I going The surface language is ambiguous, but our thoughts are not confused. They can distinguish these deep sentences: I’m going to the financial-bank going(I, financial-bank) I’m going to the river-bank going(I, river-bank) Arguments for mentalese (cont.) 4) Tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon We know what we want to say, but we can’t think of the word – i.e. we have the concept in mentalese but we can’t think of the word in English or in whatever our native natural language is. 5) Non-linguistic thought Higher animals, pre-linguistic children and children that have never been able to learn a language can still think, and still have concepts. Arguments for LOT being a natural language Simplicity: • No need to posit two systems: mentalese and natural language • No need for innate concepts Intuitive: • It seems like we think in English/Chinese/other natural language (but then there would be as many LOTs as there are NLs!) Evidence from non-linguistic children • Pre-linguistic children and children deprived of the chance to learn a language appear to be constrained in their ability to think and have poor conceptual abilities. A hybrid theory Sterelny upholds a hybrid theory. People start with a basic language-like system with few simple concepts. In learning a natural language, they develop greater language abilities and develop the vast majority of their concepts. People then think in their natural language. Readings Optional Readings: Churchland, Paul (1981) “Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes” The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 78, No. 2 (Feb., 1981), pp. 67-90, Dennett, Daniel (1991) “Two Contrasts: Folk Craft versus Folk Science and Belief versus Opinion” in Brainchildren More optional readings: (On modularity) Prinz, Jesse, (2006), “Is the mind really modular?” www.unc.edu/~prinz/PrinzModularity.pdf