South Africa in the Apartheid Era – A Unique Road to Independence

advertisement

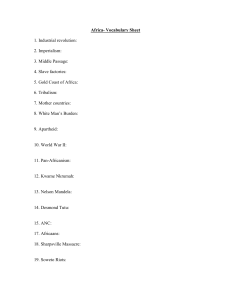

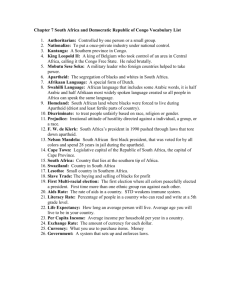

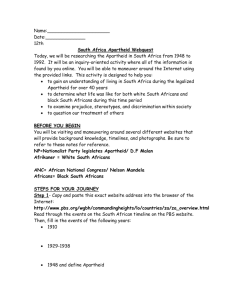

Global Independence Stations Station 3 – South Africa and the Apartheid Name _______________________________________ Date ________________________ Core ______ Videos: Nelson Mandela – Mini Biography (6:49 mins.) Mandela – The Rebel (3:23 mins.) Apartheid Explained (2:56 mins.) African Independence Movements Africa was unique among continents after WWII in that virtually the entire continent was under colonial rule. Indeed, over the past few hundred years France, Portugal, Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, and Italy had divided up its territory and resources between themselves. As a result, the African experience of decolonization varies wildly. For example, many British colonies were granted their independence with little bloodshed in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In contrast, Portuguese colonies that became the states of Angola and Mozambique were required to fight long, hard wars of independence. The decolonization of Africa - be it through war or peaceful means - took place mainly between 1956 and 1975. African decolonization started in North Africa, with the independence of countries like Egypt, Sudan, Morocco, and Tunisia, and soon spread throughout the continent. The year 1960 was particularly important. In fact, it is often referred to as the 'Year of Africa' because in 1960 alone, 17 independent nations emerged The Impact of African Decolonization The decolonization of Africa between the 1950s-1970s had both positive and negative consequences. On one hand, it allowed African groups to throw off foreign rule and institute self-government. It also led to support for what is called Pan- Africanism, which is the belief that there should be solidarity among Africans everywhere and that all of Africa should be united as one single entity, like the “United States of Africa,” to quote Kwame Nkrumah, leader of the independence efforts in Ghana. Some new African leaders believe in the dream of Pan-Africanism, that regardless of national boundaries, all black African peoples shared a common identity and unity. Pan-Africanism was supported by leaders such as Leopold Senghor of Senegal, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and Kwame Nkrumah. Even though the dream was never realized, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), was founded by 32 African states in 1963, to improve unity among its members. In 2002, the African Union (AU) replaced the OAU, with 53 members joining with aims to promote democracy and economic growth in Africa. On the other hand, decolonization also resulted in decades of inter-African strife in certain areas. With European powers absent, some regions experienced civil war as different groups competed for power. Another problem that many new African nations dealt with was the inexperience in running a country, which had previously been done by their European colonizer before independence. In several newly independent Africa countries, fighting and war continued for decades. Generally speaking, however, the decolonization of Africa was a good thing, as it brought the continent into the fold of global affairs. South Africa in the Apartheid Era – A Unique Road to Independence Unlike many African countries, independence for South Africa came not at the end of a long, nonviolent struggle, nor at the end of a drawn-out war, as was the case in Algeria. Instead, South Africa had gained some measure of recognition by 1910, from the British, and was largely independent by 1931, before WWII. A major part of this was due to the unique makeup of South African society. Whereas British colonials made up the majority of the European population in practically every other British colony, that was not the case in South Africa. Instead, descendants of Dutch settlers made up the majority of the white people in South Africa. This is because the Dutch were the first to establish a colony in South Africa, only to lose their colony in South Africa to the British. South Africans of Dutch ancestry, were known as Afrikaners or as Boers, had already fought one costly war against the British, and if white society was going to survive, Afrikaners and British settlers would have to have a common purpose. Soon, it became clear that a common purpose for both Afrikaners and British settlers could be maintaining control. After all, they were very much the minority in South Africa. As a result, regulations started to be passed to limit the rights of non-white South Africans. The Apartheid System By 1948, these rules were passed into law, and the Apartheid system was born. Apartheid literally means 'apartness' in Afrikaans, the language of the Dutch settlers, and was a system by which society in South Africa was split into four main castes: White, Black, Mixed, and Asian/Indian. Caste determined everything, from what university you could attend and what tax rate you'd pay, to even what bench you could sit on while waiting for the bus or at which beach you could spend a Saturday afternoon. The system managed to survive for nearly 50 years due to the fact that it forced white South Africans, both British and Dutch, to agree on it to maintain any level of political power. Furthermore, all citizens were forcibly relocated to a designated homeland, known as Bantustans. Upon moving to a Bantustan, one lost South African citizenship and was restricted to move around the rest of the country. Although about 4 out of 5 South Africans were black, they received only 15% of the land. Most of the natural resources, productive farmland and developed cities were designated as white territory. Non-whites who worked in white territory required a pass to enter, known as Pass Books. These Pass Books contained information about who you are, where you lived, they even had a picture of you and where you worked. Employers (which were only allowed to be white) were allowed to write in your Pass Book about your behavior and conduct as a person. The Pass Books determined which areas you were allowed in and for how long. If you did not have your Pass Book and you were out of your “designated area,” you were arrested and relocated to your “designated area,” or sent to prison. The few who were granted permission to live in the cities were relegated to slums, called townships. Most contact between racial groups was banned. South African Resistance Of course, black South Africans had been consistently fighting discrimination and white minority rule, but in 1948, apartheid made their protests illegal. Still, several groups emerged in the 1950s dedicated to ending apartheid and some began burning their pass books in protest. The African National Congress, led by Nelson Mandela, arranged various acts of civil disobedience, boycotts and other forms of protest. The Pan Africanist Congress, which had split off from that group, organized an act of passive resistance in 1960. Hundreds of blacks arrived at the police station in Sharpeville (a black township) without their passes, fully expecting to be arrested. But the police opened fire on the crowd, killing 67 people and injuring 180 more, this became known as the Sharpeville Massacre. The Sharpeville massacre galvanized the anti-apartheid movement, and convinced some groups to shift their methods from Gandhi's non-violence to more aggressive guerrilla tactics. Within a year, both the ANC and the PAC were outlawed, and most of their leaders were imprisoned or exiled. Nelson Mandela was convicted of sabotage, and sentenced to life in prison. From this lack of leadership came Desmond Tutu, the first black leader of the Anglican Church in South Africa. As he rose through the ranks of religious politics, he continually advocated for an end to apartheid. 'The black cause of liberation will triumph...' Tutu said in 1981. 'God is on our side because he is always on the side of the oppressed. The only questions are how and when freedom will come. We want it now and we want it to come reasonably peacefully. Whites have to decide whether they want it to happen by negotiation or through violence and bloodshed.' It was through the efforts of Desmond Tutu and the Sharpeville Massacre, the apartheid and the problems would receive international recognition. Although the United Nations failed to impose effective sanctions against South Africa, by the late 1970s, individual nations and corporations began their own embargoes (stopped trading with South Africa) of the apartheid regime. And from 1956, many sports organizations (such as the Olympics) banned South Africa from participation. On June 16, 1976, when thousands of black children in Soweto, a black township outside Johannesburg, demonstrated against the Afrikaans language requirement for black African students, the police opened fire with tear gas and bullets, this became known as the Soweto Uprising or Protest. The protests and government crackdowns that followed, combined with a national economic recession, drew more international attention to South Africa and shattered all illusions that apartheid had brought peace or prosperity to the nation. International opposition to apartheid finally gained steam after 1984, when Bishop Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize. The United States passed the Anti-Apartheid Act in 1986, prompting several multinational corporations to boycott South Africa. By the end of the decade, South Africa's economy was struggling under the economic sanctions. The End of Apartheid The effects of domestic and international pressure forced South Africa's president to resign in 1989, starting a snowball effect that finally led to the fall of apartheid. Incoming President, F.W. de Klerk, stunned the world with a series of reforms. He lifted the ban on the African National Congress and other anti-apartheid organizations. Suddenly, after 27 years in prison, Nelson Mandela, along with many other political prisoners, was released in 1990. With a free press also reinstated, Mandela spoke openly about apartheid to anyone who would listen, including the United States Congress. With the Cold War finally at an end by this time, the Western democracies could no longer justify the apartheid regime in South Africa and began applying even more diplomatic and economic pressure. President de Klerk systematically undid the apartheid laws, granting full rights to all South Africans by 1993. But when non-whites were finally allowed to vote in South Africa's first democratic elections, de Klerk lost his job. Nelson Mandela was elected in a landslide in 1994, and the honor of introducing South Africa's first black president fell to Bishop Desmond Tutu (F.W. de Klerk would become Nelson Mandela’s Vice President). It took nearly five decades, but South Africa finally threw off the racist apartheid regime and embraced majority rule. For their efforts to achieve political equality in South Africa, deKlerk and Mandela were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. Truth and Reconciliation Commission Given the deep wounds caused by the apartheid, there was a real fear that the formerly discriminated citizens would strike back at the white minority and violence would spread throughout South Africa. To counter this, Mandela and de Klerk set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to not only find out the abuses that happened during the apartheid, but to give individuals the opportunity to confess their wrongs and find forgiveness from the state itself. In fact, the commission especially welcomed input from individuals who had been members of the opposition, particularly the African National Congress, who had committed acts of politically-inspired hate against the white minority. While the commission did face considerable criticism, it is widely believed in South Africa to have helped prevent violence after the end of the apartheid. Sources: https://study.com/academy/lesson/decolonization-and-nationalism-in-israel-egypt-africa-indonesia-vietnam-algeria.html https://study.com/academy/lesson/changes-in-africa-after-world-war-ii.html https://study.com/academy/lesson/south-africa-in-the-apartheid-era.html https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-end-of-apartheid-south-africa-in-the-1990s.html http://www.history.com/topics/apartheid