Self-Concept - School Psychologists Association of Southeast

advertisement

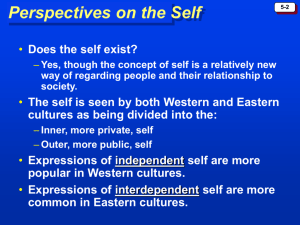

Self-Concept: Assessment and Intervention Ellie L. Young, PhD, NCSP Laura Hoffman, MEd, Graduate Student Ana Kemple, Graduate Student Brigham Young University Objectives • Participants will understand theoretical foundations of self-concept • Participants will learn about current measures of self-concept/self-esteem • Participants will understand how development and diversity issues influence self-concept • Participants will understand effective interventions for helping students develop healthy self-concept Theoretical Foundations • What is self-concept? – Perception of self • Perceptions formed by experiences • Influenced by environmental reinforcers and significant others • Inferred from behavior • What is self-esteem? • Seven features – Some say it is subsumed in self-concept – Some say it is the evaluative component in self-concept – Some say it is the same as self-concept – – – – – – – organized multifaceted nature hierarchical structure stable developmental progression evaluative component differentiable characteristics What connection does self-concept have to mental health, academic success, life in general? • High self-esteem is related to – – – – Academic success Positive mood and happiness Life satisfaction Physical fitness and desirable health practices – Social and interpersonal relationships – Better coping skills Aggressive behavior is related to unrealistically high self-concept When a child has unrealistically high self-concept and feels threatened, she or he may act out to protect feelings of adequacy. • Low self-esteem is related to – DSM Disorders • Eating disorders • Depressive disorders • Anxiety disorders – Interpersonal problems • loneliness – Learning difficulties – – – – – • When children experience success in a resource environment, their selfesteem tends to increase Substance use Gang membership Obesity Suicidal tendencies Teen pregnancy What can school psychologists learn through assessing self-concept? • Understand how the child views him/herself – Ipsative evaluation • Attend to both positive and negative self-evaluations – What strengths does the child believe he/she has? – What weaknesses does the child perceive in self? – How can these strengths or weaknesses be used in designing interventions? • To consider depressive/mood disorders • Other . . .? Self-Concept and Self-Esteem Measures • • • • • • • Age Items Dimensions Norms Reliability Validity Diversity Tennessee Self-Concept Scale – Second Edition • 76 items on child form 5 pt scale • Age: 7-90 (child form 7-13: adult form 13 +) • Dimensions: Physical, moral, personal, family, social, and academic/work • Norms: Nationally normed, renormed • Reliability: Internal consistency 73-.93 test-retest .55-.83 • Validity: construct, concurrent • Diversity: claims there are no sex, ethnic, education, or socioeconomic differences in means Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory • Age: 8-15, 16+ • 58 forced choice items • Dimensions: General self, Social self-peers, home-parents, school/academic, total self, lie scale • Norms: Locally normed in Connecticut • Reliability: Internal consistency-.80-.90, testretest .88 • Validity: concurrent, construct, criterion-related, predictive • Diversity: none noted Self-Description Questionnaire-I • Age: 5-12 • 76 forced-choice items • Dimensions: physical abilities, physical appearances, peer relations, parent relations, reading, mathematics, general-school, general self, nonacademic, academic, total self • Norms: Normed in foreign country- Australia • Reliability: internal consistency- total .94 scales- .80-.92 • Validity: construct and concurrent, cross national validity needed • Diversity: none noted Self-Description Questionnaire-II • Age: 13-17 • 102 forced-choice items • Dimensions: Physical, appearance, oppositesex, same-sex, parent, honesty, stability, math, verbal, general school, general self, total score • Norms: Normed in Australia • Reliability: internal consistency- total-.94 scale- .84-.91 • Validity: construct reported cross national validity needed • Diversity: none noted Multidimensional Self Concept Scale • Age: grade 5-12 • 150 likert-type items • Dimensions: Social, Competence, Affect, Academic, Family, Physical, Total self • Norms: Nationally normed • Reliability: internal consistency- total .98 scales .87-.97; test-retest- total .90 scales .73-.81 • Validity: construct, content, concurrent, contrasted groups, divergent • Diversity: shown not to discriminate Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale • Age: Grades 4-12 • 80 forced-choice items • Dimensions: Behavior, intellectual/school, physical appearance attributes, anxiety, popularity, happiness/satisfaction, total self • Norms: Locally normed on Pennsylvania school system • Reliability: internal consistency- total .90 scales .88-.93; test-retest- .42-.96 • Validity: contrasted, construct, content, concurrent, comparison of raters • Diversity: Description of use with minority and diverse populations included in manual Self-Concept in Childhood • Ages 5-7 – Self-representations are positive and virtuosity is overestimated – References to self based on competencies • social skills, cognitive abilities, and athletic talents – Unidimensional thinking (all-or-none thinking) is present • “I am good therefore I can’t be bad” • Ages 8-11 – Descriptive terms • popular, nice, smart, dumb, etc – Descriptions of self become contingent on relationships – Personal traits become situation specific • “I’m smart in math but dumb in reading.” Adolescence • Early Adolescence – Social attributes and competencies influence self-representations. • “I’m a cheerful person and I’m also intellectual. – Development of multiple selves, which the youth can utilize to function in a variety of social contexts. – Youth engage in all-or-none thinking at an abstract level, which leads to an inability to integrate single abstractions of the self into different relational contexts. – This may lead to unrealistic representations of the self at certain points in time • one may very intelligent at one time, whereas another time one may feel stupid • Middle Adolescence – Preoccupation with what significant others think of the self. – Youth make finer discriminations in peer relations • self with a close friend versus self with a group). – Youth must now compare and contrast different attributes of the self. – Contradictions discovered in this comparison lead to conflict, confusion and distress in the youth. – Self-attributes that oppose each other can weaken self-representations and concern over what characteristics represents the true self. Age Differences in SelfConcept • As children age, their exposure to new experiences, environments, opportunities, and reactions from others help them acquire and develop domain-specific selfconcept. • Some researchers have found that global self-concept declines with the advent of adolescence while others have found that is remains relatively stable. • Bracken found that although domain-specific self-concept appeared to increase with age, results were not found to be qualitatively or practically meaningful. • Kling, et. al, found that between the ages of 13 and 32, self-esteem in both males and females is relatively stable and even shows signs of gradual increase. Race/Ethnicity • Claims of race differences in self-concept have been limited and inconsistent in direction and magnitude. • Some research suggests that Hispanic children have lower global self-concepts than African American and European American children. • Some research has found that European American students report higher global self-concept than their culturally diverse peers while other research reports the opposite. • One study reported that for ethnic minority adolescents, the combination of a troubled historical past and the challenges of current oppression and discrimination can be barriers to the development of a positive identity. Race/Ethnicity cont’d… • A more specific study postulated that African American girls disidentify with the criteria that European American adolescents use to evaluate their self-worth. • African American girls were higher than European American girls on confidence of their femininity, masculine skills, physical attractiveness, popularity and the difference between their educational aspiration and actual expectations. • European American girls were higher on worrying about their weight and social self-consciousness. • When comparing the two groups based maturational rate, pubertal development was much less pervasive for African American girls, which protected their self-esteem. • Research suggests that this resiliency comes from the structure of the home, which typically has a female head of household and a matriarchal family structure. Race/Ethnicity cont’d… • Studies regarding ethnic differences suggest that the identification with family and community provides strength and resources for adolescents when challenged with conflicting expectations, racial discrimination, and class distinction. • One theoretical model proposes that stigmatized groups (e.g. African Americans) protect their self-concept by – a) attributing negative feedback to prejudice against their group – b) comparing their success or failure with people within their own group, versus the majority group – c) imposing higher values in what their group can do well versus what they cannot do well. Race/Ethnicity • Although European American students reported higher academic achievement, African American students reported higher self-esteem despite poorer academic performance. • African American males begin to disidentify with their academic success as they progressed through school, and that this disidentification allowed for their self-esteem to be protected • The relationship between academic self-concept and GPA remained significant for African American female and European American male students. Gender and Ethnicity • Nonsignificant differences between Black males and females • Significant difference, favoring males, in European Americans • Black women tend to have higher levels of body satisfaction than European American women, due to a lessened pressure toward thinness among Blacks. Gender and Self-Concept • Ambiguity exists as to whether there are differences in selfconcept. • Research from meta-analyses suggests that there is a consistent gender difference in self-esteem, albeit small, favoring males. Although differences are seen between genders at the onset of puberty, the difference is not a large one. • The most notable areas for the differences seen are in the areas of physical abilities and physical appearance, where boys appear to have slightly higher levels of self-concept. • Girls evidenced significantly higher levels of self-concept in the areas of Verbal, Close Friendship, and Same Sex Peer Relationships. Boys were higher in Math, Athletic/Psychomotor Coordination, and in the Emotional/Affect and Freedom from Anxiety areas. Perspectives on Gender Differences in Self-Esteem • Peer Interaction – Boys’ groups are oriented toward dominance where as girls’ groups are oriented toward shared social activities. – When in unsupervised mixed-gender group, girls tend to see themselves as less powerful, which could adversely affect their self-esteem. • Schools and Teachers – Teachers interact with boys more frequently and give more specific and helpful feedback. – Teachers tend to attribute boy’s failures to motivational problems and girls’ failures to lack of ability. • Cultural Emphasis on Appearance – Women and girls consistently report greater dissatisfaction with their appearance and their bodies than boys and men do. – Perceptions of physical attractiveness are more strongly associated with self-esteem for girls than for boys. • Athletic Participation – Participation in athletics is associated with high self-esteem among male and female students. – Historically, boys have had more access to this source of self-esteem. Gender Differences – Gender differences in self-esteem are small despite the numerous assaults on girls’ and women’s self-esteem. – Benefits girls have experienced may have been at the cost of boys • Although athletic success is typically seen as a male role, not all boys are athletes. These boys are failures in a highly salient aspect of the male role • Bias portrayed in the media about the expected detrimental decline in female adolescent self-concept may lead to self-fulfilling behaviors in females. – Gender Roles and their effects on self-esteem • Girls who were described by others at the age of 14 as being nurturing, sympathetic or a source of reassurance reported increases in self-esteem from age 14 to 23. • Qualities correlated with an increase in the self-esteem of boys across this same period include being socially at ease, feeling satisfied with self, and behaving in a masculine manner. Interventions • Use a theoretical and empirically based intervention model • Interventions focused on reducing behavior problems did increase selfesteem • Target interventions at the sub-domain level (i.e. academic or physical self-concept) rather than global self-esteem • Teach coping strategies to minimize short-term fluctuations in feelings of self-worth • Teach problem-solving and social skills – Be honest with students—sometimes they do stupid things—they know it—you know it—help them accept the consequences in a matter-of-fact way and brainstorm ways to perform differently next time • Provide opportunities for recognition of positive behaviors – Service learning – Academic improvement or accomplishing student-centered goals • Increase academic or other skills • Making goals and monitoring progress through charts Interventions • Cognitive ‘therapy’ approaches – Identify catastrophic thinking and teach more flexible thinking patterns – Teach that cognitions determine emotions • Allow children to fail, to accept the consequences, to learn from mistakes, to do better next time. – Avoid rescuing students when they experience failure – Provide support and encouragement as they face the consequences of their decisions • “I know you can do better next time.” • Create a safe environment where students can feel comfortable taking risks, experiencing failure and success and learning from the process of stepping out of their comfort zone. For more information contact Ellie L. Young, Department of Counseling Psychology and Special Education 340-P MCKB Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 Email: ellie_young@byu.edu