Where are crack babies going?

advertisement

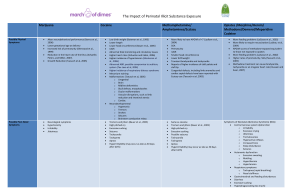

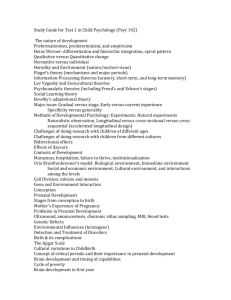

Prenatal drug (cocaine, opiates, alcohol) exposure Messinger Questions What is Frank et al.'s thesis about the current scientific literature (their major argument)? Describe typical levels of medical and social risk (including other types of exposure) in cocaine exposed children. Summarize findings from the Maternal Lifestyle Study with respect to 4 month interaction, 18 month attachment, and Bayley mental, motor, and behavioral development between 1 and three years. Describe the bolded pathways leading 7-year behavior (CBCL) problems in Lester et al. (2009). Do you see a potential problem with any of those pathways? Describe the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on childhood behavior in Sood et al. What is a dose-response effect? Is maternal prenatal substance exposure child abuse? In your view, What Messinger substances would and would not constitute abuse? Crack Babies: Twenty Years Later http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.ph p?storyId=126478643 Encouraging news on babies born to cocaine-abusing mothers - The New... http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/27/world/ americas/27iht Messinger Is maternal prenatal substance exposure child abuse? What substances would and would not constitute abuse? Overview (Frank) Prenatal cocaine exposure does not appear to have a uniquely detrimental impact on the developing child Other risk factors – such as prenatal alcohol exposure, premature birth, low maternal education and socioeconomic status – have at least equally detrimental impacts on the developing child. Messinger Review of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure Issues in the Study of Cocaine Exposure – Findings Contamination Preconceptions about the population Blindness to exposure – Confounding factors Low SES Co-occurring exposure to other teratogens – Mattson Prospective vs. Retrospective A Review of the Effects of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure Among School-Aged Children Messinger Ackerman, J. P., Riggins, T., & Black, M. M. (2010). A Review of the Effects of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure Among School-Aged Children abstract. Pediatrics, 125(3), 554-565. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0637 Systematic Review of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure and Adolescent Development Stacy Buckingham-Howes, Sarah Shafer Berger, Laura A. Scaletti and Maureen M. Black Messinger 27 studies representing 9 cohorts. Of 11, 7 found small but significant differences with small effect sizes. 8 examined cognition/school performance; 6 reported significantly lower scores on language and memory tasks among adolescents with PCE, with varying effect sizes. Most studies controlled for other prenatal exposures, caregiving environment, and violence exposure. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1917–e1936 How big of a problem? 45,000 (~1.1%) mothers report cocaine use – Higher if unmarried, not working, less educated 0.1% for opiate use 18.8% (757,000) of mothers reported alcohol use during pregnancy 20.4% (820,000) reported cigarette use • Messinger (NPHS ‘92-’93) Messinger Perceptions of cocaine exposure Drug of poor (crack) – Quick acting, highly addictive, cheap Use during pregnancy - child abuse? – Teachers ‘know’ that exposed children perform more poorly Can you tell the difference? – Messinger 200 women prosecuted in 30 states since 1985 Final project experiment Video An early rush to judgement Fetal development – Neonatal/perinatal outcome – SIDS, poor feeding, hypertonia, & irritability Development (from anecdotal reports) – Messinger Spontaneous abortion & prematurity distractibility, hyperactivity, impulsivity, aggressiveness, & language delays Current scientific literature “Among children aged 6 years or younger, there is no convincing evidence that prenatal cocaine exposure is associated with developmental toxic effects that are different in severity, scope, or kind from the sequelae of multiple other risk factors. Many findings once thought to be specific effects of in utero cocaine exposure are correlated with other factors, including prenatal exposure to tobacco, marijuana, or alcohol, and the quality of the child's environment.” • Messinger Frank, et al. (2001). Design issues Previous problems – Small sample sizes Current solutions – Large sample – Lack of matching – Follow-up matching on – Messinger Lack of statistical controls – 4 centers gestational age, gender, and race Ability to statistically control for associated risks Exposure defined Cocaine: Admitted use during the maternal hospital interview and/or cocaine metabolites in meconium Opiates: Admitted use during the maternal hospital interview and/or opiate metabolites in meconium – Messinger central laboratory gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy Cocaine exposed neonates are slightly smaller Characteristics Absolute Cocaine/ Opiate Difference Gestational Age (Ballard) -1 week Adjusted Cocaine Difference at GA > 32 Weeks --- Birthweight (g) -465 g -168 g Length (cm) -2.4 cm -.77 cm Head Circum.(cm) -1.4 cm -.49 cm No opiate differences Smoking and heavy drinking also associated with smaller size Bada Messinger et al., 1991; Bauer et al., 1991 Risk for Central Nervous System/autonomic Nervous System (CNS/ANS) Signs Bada et al., 2002 Cocaine increased risk of manifesting a constellation of CNS/ANS outcomes, OR (95% CI): 1.7 (1.2 to 2.2) Opiate effect, OR (95% CI): 2.8 (2.1 to 3.7). Opiate+Cocaine had additive effects, OR: 4.8 Smoking also increased the risk OR (95% CI) of 1.3 (1.04 to 1.55) less than half a pack per day ; 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) half a pack per day or more. Cocaine or opiate exposure increases the risk for manifesting a constellation of CNS/ANS outcomes even after controlling for confounders – 11,811 maternal/infant dyads were enrolled. Messinger Of 1185 EXP, meconium analysis confirmed exposure in 717 to cocaine only, 100 to opiates, and 92 to opiates plus cocaine High levels of medical / social risk Present in both groups - higher in the exposed group COCAINE/OPIATE Birthweight (% < 2500 g) Married (%) Education <12 years (%) Medicaid (% Yes) Messinger EXPOSED COMPARISON (N=658) (N=730) 4190.00% 10.3 49.4 85 4170.00% 24.7 31.3 79.5 Tobacco, marijuana, & alcohol Present in both groups - higher in the exposed group Tobacco use (% Yes) Marijuana use (% Yes) Alcohol use (% Yes) Cocaine use (% Yes) Opiate use (% Yes) Messinger COCAINE/OPIATE EXPOSED COMPARISON (N=658) (N=730) 82.8 28.3 37.8 9.1 73.3 48.5 91 0 17.1 0 1 month neurobehavioral exam Simple comparisons (univariate) Cocaine exposed show poorer movement quality – 4.43 vs. 4.49 No consistent cocaine differences on measures of: Attention, Arousal, Regulation, Handling,, Excitability, Lethargy, Non-optimal Reflexes Asymmetrical reflexes, Hypotonia, Hypertonia, or signs of Stress Abstinence (Lester et al., 2002) Messinger Controlling for other risk factors Cocaine exposed infants were – less aroused (lower – less stable self-regulation (less – ability to regulate crying) Small differences (e.g. behavioral state) .02-.07 on 7-point scale) (Lester et al., 2002) Similar isolated reports of early state regulation difficulties in the literature Messinger Differences while feeding? No infant cocaine differences on sucking / feeding But cocaine-using mothers were less flexible and engaged; had shorter feeding sessions – Even when controlling for other risks Opiate-exposed infants showed prolonged sucking, fewer pauses, more feeding problems (e.g., spitting up), and increased arousal – Their mothers showed increased feeding related activity, independent of their infants’ feeding problems. • Messinger LaGasse, Messinger et al., 2003 4 month face-to-face interaction No differences in infant smiling & sociality. Cocaine moms more negative – – Heavy exposed caregiver infant-dyads – – Messinger More negative when infant neutral More mismatched in general Infants more passive negative Dyad shows more negative matching Even after controlling for other risk factors Does this have a continuing effect? No differences in free-play at 18 months (Miami) Caregiver requests, toy offers, positive and negative vocalizations, or sensitivity Toddler toy offers, looks to caregiver, smiles, and joint attention bids; Dyadic variables indicating the proportion of caregiver and toddler requests and toy offers fulfilled by the other partner. Messinger No exposure attachment effects Level of prenatal cocaine exposure not significantly related to secure/insecure attachment status, disorganized attachment status, or rated level of felt security. Foster care status also not associated with attachment status. – But heavier prenatal cocaine exposure, in interaction with contextual variables (public assistance or multiparity) associated with a higher level of behavioral disorganization, more avoidance of the caregiver, and less crying. • Messinger Beeghly et al (2003) Cocaine summary Cocaine exposed neonates are slightly smaller than non-exposed infants. Slight, scattered decrements in self-regulation (after covariate control) at 1 month were not detectable in infant feeding behavior, 4 month interaction, or Bayley mental, motor, or behavioral development between 1 and three years. Although cocaine caregivers were less involved at 1 & 4 months, there were no differences in secure attachment or quality of play at 18 months Standardized measures of development? Messinger Mental (MDI) Cocaine Effects Unadjusted MDI 96 93 No Cocaine Cocaine 90 • 87 84 81 Cocaine exposure was associated with an average 1.6 point MDI decrement Not significant after adjusting for covariates. – 78 1 Year Messinger 2 Year 3 Year (P = .0075). Site, birth weight, SES, vocabulary, maternal care. Psychomotor (PDI) Opiate Effects Unadjusted PDI 96 93 90 87 84 No Opiate Opiate 81 78 1 Year Messinger 2 Year 3 Year Opiate exposure was associated with an average 4 point PDI decrement (P = .0023). Not significant after adjusting for covariates (P = .0361). – Site, birth weight, SES, HOME Behavior Rating Scale (BRS) Messinger Neither cocaine (P = .799, 0.26 percentile difference) nor opiate exposure (P = .075, 4.5 percentile difference) was associated with overall differences in BRS ratings Covariate Effects Low infant birth weight associated with lower overall MDI, PDI, and BRS, – Indices of higher quality caregiving associated with higher BSID-II scores. – – – – Messinger but did not moderate cocaine or opiate exposure effects. Higher HOME scores with higher PDI and BRS. Higher vocabulary scores with higher MDI and BRS. Consistent mother with higher MDI and PDI. Poverty status associated with lower BRS. Partially responsible for sharp decline in mental performance after one year for all groups • (Messinger et al., 2003) Standardized tests of cognitive achievement, motor performance, and language development Often show no significant exposure effects Effects, when present, tend to be of small magnitude – Messinger Although Singer found cocaine deficits in mental performance (and motor performance), Frank did not. Cognitive cocaine exposure deficit – in some studies “6-point deficit in Bayley Mental Scales of Infant Development scores at 2 years, with cocaine-exposed children twice as likely to have significant delay (mental development index <80).” – Controlled for confounding variables “Four hundred fifteen consecutively enrolled infants (218 cocaineexposed and 197 unexposed) identified from a high-risk, low– socioeconomic status, primarily black (80%) population screened through clinical interview and urine and meconium samples for drug use. – – Messinger The retention rate was 94% at 2 years of age. Singer et al., 2002 But not in all studies No significant adverse main effects of level of cocaine exposure on Mental Development (MDI), Psychomotor Development (PDI), or Infant Behavior Record. Interactions: – – heavily exposed children who received child-focused early intervention – highest adjusted mean MDI scores “heavier exposure group born at slightly lower gestational age - higher mean MDI scores than other children of that gestational age – Messinger Although the sample was born at or near term interaction of cocaine exposure and gestational age Frank et al. Interaction: child age & caregiver The adjusted mean MDI of children in unrelated foster care at 6 months was 8.2 points lower than children of biological mothers, whereas it was 7.3 points higher at 24 months. At 6 months, the adjusted MDI of children living with a kinship caregiver was 15.5 points lower than that of children living with their biological mother, – effect no longer significant at 24 months difference in means: 4.3 points. Frank et al. Messinger Motor differences Cocaine-exposed group performed significantly less well on both the fine and the gross motor development indices. – – Mean scores for both groups were within the average range on the gross motor index, but greater than 1 standard deviation below average on the fine motor index. There also was an effect of alcohol exposure on the receipt and propulsion subscale. • Messinger Arendt . . . . Singer (1999) Cocaine summary Cocaine exposed neonates are slightly smaller than non-exposed infants. Slight, scattered decrements in self-regulation (after covariate control) at 1 month were not detectable in infant feeding behavior, 4 month interaction, or Bayley mental, motor, or behavioral development between 1 and three years. Although cocaine caregivers were less involved at 1 & 4 months, there were no differences in secure attachment or quality of play at 18 months Messinger Conclusions As in other studies, cocaine exposure had little impact on developmental outcome Exposure differences that did exist were small. Nevertheless, even small deficiencies in the performance of older cocaine exposed children remain a cause of social concern. Messinger Impact of Small Cocaine Effects: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using School-Age Children Measure Effect (SEM) Percent Increase Affected < 2 SD Children Service Cost IQ difference (n=5) 3.26 (2.01) IQ points 3.75 1.6x 1,688 14,062 $4-35 million Expressive Language (n=5) .60 (.29) SD units 8.08 3.5x 3,636 30,300 $17-138 million Messinger (Lester et al., 1998) 7 Year MLS Follow-up 100 Predicted Mental Functioning Over Time 80 60 70 Predicted IQ 90 No Cocaine Cocaine 1 2 3 4 Age (Years) Messinger 5 6 7 The cocaine deficit increased as children reached school age. There was an overall cocaine related deficit of 1.45 IQ points (p<.02) (see Figure). However, this deficit increased at older ages (p = 0.003). At 4 ½ years of age, the deficit was 3.35 points, while at 7 years it increased further to 4.4 points. Lower birthweight, SES, and maternal vocabulary were also associated with decreasing performance with age. – Messinger These risk factors were common and partially explain the entire sample’s decrease in test scores with age. Cocaine exposure influences sustained attention at 3, 5 and 7 Stable cocaine-specific effect on sustained attention processing. “Each standard deviation increase in level of prenatal cocaine exposure 16% standard deviation increase in omission error scores at 7. – Messinger Bandstra ES, Morrow CE, Anthony JC, Accornero VH, Fried PA. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001 23(6):545-59. Longitudinal investigation of task persistence and sustained attention in children with prenatal cocaine exposure. Subtle special ed effects at age 7 Prenatal cocaine exposure … effect on individualized education plan, but only when controlling for low IQ. – When low child IQ was not included in the model, prenatal cocaine exposure had a significant effect on support services. Male gender, low birth weight, white race, and low child IQ also predicted individualized education plan. Low birth weight and low child IQ were significant in all models • Messinger Pediatrics. 2008 Jul;122(1):e83-91. Epub 2008. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on special education in school-aged children. Levine TP, Liu J, Das A, Lester B, Lagasse L, Shankaran S, Bada HS, Bauer CR, Higgins R. Jury out? Messinger Differences associated with cocaine exposure and other risk factors were associated with a widening deficit in child IQ. The impact of cocaine exposure became more evident at later ages when demands for higherlevel cognition become more prevalent (e.g., school performance). The, “jury is still out” on the long-term effects of prenatal exposure. Provisos Compliance – High risk samples - high variability – Messinger Difficulty in discerning specific effects Generalizable only to similar high-risk samples Multiple risks come together – Heaviest users Polydrug use, low SES, low birth weight Older kids Unique? Messinger “There is no convincing evidence that prenatal cocaine exposure is associated with any developmental toxicity different in severity, scope, or kind from the sequelae of many other risk factors.” (Frank et al., 2001, pp. 21-24) Behavior Problems in Children With Prenatal Substance Exposure Messinger What about other drugs? Messinger Prenatal tobacco exposure costs $263 million in neonatal health costs alone Alcohol is a known teratogen High levels associated with fetal alcohol syndrome Lower levels negatively affect cognitive development through lifespan In infancy, there is a dose-response relationship between prenatal alcohol exposure (AA/day, 0 2+) and mental and motor development (Jacobson et al., 1993). Prenatal Alcohol Alcohol impacts prenatal development by impairing and altering the development of fetal brain structures. Extensive alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with the altered facial characteristics, reduced growth, and severe cognitive deficits of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). – Messinger http://scan.missouri.org/~willowpd/EffectBaby/fas_cau ses.html Current issues Improved identification of occurrence of maltreatment Examination of its consequences – What determines effect of abuse? Establishing adequate services and supports for families and children to protect from exploitation and harm Continuum of Severity Messinger Prenatal alcohol exposure has been shown to result in a broad spectrum of negative outcomes for the developing child. The nature and degree of such effects appear to fall along a continuum of severity. Where the child falls along this continuum depends upon the timing, the extent, and the chronicity of the prenatal exposure to alcohol (Phelps & Grabowski, 1992). Alcohol effects are dosedependent. Messinger “Readily apparent relationships between the quantity of alcohol consumed and subsequent deficits and problems in the child. Less obvious effects of alcohol exposure include reductions in general intelligence and verbal learning as well as problems with social functioning. Attention problems, memory deficits, and motor skills problems have been associated with habitual social drinking by the expectant mother throughout the pregnancy Is alcohol use child maltreatment? Prenatal exposure to alcohol affects one in four births – one in twelve mothers reporting binge drinking during the pregnancy The Effects Of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure On Infant Mental Development: A Meta-analytical Review Fetal alcohol exposure at all three dosage levels was associated with significantly lower MDI scores among 12–13-month-olds. – – 1 drink, 1–1.99 drinks, and > 2 drinks per day among 6–8-, 12–13- and 18–26-month-olds. effect not eliminated, when adjusted for covariates Messinger Testa, Quigley, & Das Eiden Alcohol and Alcoholism 38, 4, 295-304, 2003 12 Month effect Messinger Heavy Exposure Messinger Habitually heavy alcohol consumption (3 or more drinks per day) and/or one or more first-trimester alcoholic binges has been shown to raise the risks of global developmental damage to the fetus (Driscoll et al., 1990). Prenatal alcohol conduct disorder? “Prenatal exposure to alcohol was associated with higher levels of conductdisorder symptoms in offspring, even after statistically controlling for the effects of parental externalizing disorders (illicit substance use disorders, alcohol dependence, and antisocial/behavioral disorders), prenatal nicotine exposure, monozygosity, gestational age, and birth Messinger weight.” Disney et al., 2008 Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Childhood Behavior at Age 6 to 7 Sood, B., V. Delaney-Black, et al. (2001). "Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Childhood Behavior at Age 6 to 7 Years: I. Dose-Response Effect." Pediatrics 108(2): e34. Messinger Individual Differences Among children with similar high levels of prenatal alcohol exposure, some will manifest severe FAS symptomatology, some will manifest mild effects, and some children will appear unaffected (Able & Sokol, 1986; Phelps & Grabowski, 1992). – Messinger Genetics? Smoking: One in five women reports using while pregnant Prenatal exposure to cigarettes is associated with premature birth, low birth weight, and irritability in the newborn. Tobacco exposure is associated with lower intelligence scores and higher risk for attention deficit disorder in school age children. Messinger Immediate postnatal smoking effects Smoking-exposed infants showed greater need for handling and worse self-regulation (P < .05) and trended toward greater excitability and arousal (P < .10) Effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy at 10 to 27 days are subtle and consistent with increased need for external intervention and poorer self-regulation. • Messinger 1: J Pediatr. 2009 Jan;154(1):10-6. Epub 2008 Nov 5. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior: effects at 10 to 27 days.Stroud LR, Paster RL, Papandonatos GD, Niaura R, Salisbury AL, Battle C, Lagasse LL,Lester B. Nicotine replacement therapy? While “Nicotine replacement therapy [e.g., nicorettes] avoids exposure to the myriad compounds present in tobacco smoke, nicotine itself causes damage to the developing nervous system. … Based on the clear, adverse effects of nicotine on brain development observed in human and animal studies, we suggest that safer alternatives for smoking cessation in pregnancy are badly needed. (Pauly & Slotkin, 2008) Messinger Methamphetamines Prenatal methamphetamine use is associated with fetal growth restriction after adjusting for covariates – – – 3.5 times more likely to be small for gestational age (sga). Tobacco 2 times more likely to be sga Birthweight in the methamphetamine exposed group was lower than the unexposed group. • Messinger The Infant Development, Environment, andLifestyle Study: Effects of Prenatal Methamphetamine Exposure, Polydrug Exposure, and Poverty on Intrauterine Growth. Lynne M. Smith, MDa, Linda L. LaGasse, PhDb,Chris Derauf, MDc, Penny Grant, MDd,Rizwan Shah, MDe, Amelia Arria, PhDf,Marilyn Huestis, PhDg, William Haning, MDh,Arthur Strauss, MDh, Sheri Della Grotta, MPHb,Jing Liu, PhDb and Barry M. Lester, PhDb. PEDIATRICS Vol. 118 No. 3 September 2006, pp. 1149-1156 Effects of prenatal methamphetamine exposure on behavioral and cognitive findings at 7.5 years of age After adjusting for covariates, children exposed to methamphetamine had significantly higher cognitive problems subscale scores than comparisons and were 2.8 times more likely to have cognitive problems scores that were above average on the Conners' Parent Rating Scale– Revised: Short Form. No association between prenatal methamphetamine exposure and behavioral problems, measured by the oppositional, hyperactivity, and attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder index subscales, were found. • Messinger Diaz, S. D., Smith, L. M., LaGasse, L. L., Derauf, C., Newman, E., Shah, R., Arria, A., Huestis, M. A., Della Grotta, S., Dansereau, L. M., Neal, C., & Lester, B. M. (2014).. J Pediatr, 164(6), 13331338. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.053 Debate Illicit drug use is uniquely toxic to the infant Illicit prenatal drug use is child abuse and should be prosecuted Licit and illicit drug use have comparable effects on the infant Both should be prosecuted. Messinger Additional readings Messinger Frank, D. A., Augustyn, M., Knight, W. G., Pell, T., & Zuckerman, B. (2001). Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(12), 1613-1625. Alessandri, S. M., Bendersky, M., & Lewis, M. (1998). Cognitive functioning in 8- to 18- month-old drug-exposed infants. Developmental Psychology, 92(3), 565-573. Alessandri, S. M., Sullivan, M. W., Imaizumi, S., & Lewis, M. (1993). Learning and emotional responsivity in cocaine-exposed infants. Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 989-997. Arendt, R., Angelopoulos, J., Salvator, A., & Singer, L. (1999). Motor Development of Cocaineexposed Children at Age Two Years. Pediatrics, 103(1), 86-92. Bauer, C., Shankaran, S., Bada, H. S., Lester, B., Wright, L., Krause-Steinrauf, H., Smeriglio, V., Finnegan, L., Maza, P., & Verter, J. (2002). The Maternal Lifestyle Study: Drug exposure during pregnancy and short-term maternal outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 186(3), 487-495. Bendersky, M., & Lewis, M. (1998). Arousal modulation in cocaine-exposed infants. Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 555-564. Dow-Edwards, D. (1993). The puzzle of cocaine's effects following maternal use during pregnancy: Still unsolved. Neurotoxicology & Teratology, 15(5), 295-296. Eiden, R. D., Lewis, A., & Young, S. C. a. E. (2002). Maternal cocaine use and infant behavior. Infancy, 3(1), 77-96. Eyler, F. D., Behnke, M., Conlon, M., Woods, N. S., & Wobie, K. (1998). Birth Outcome From a Prospective, Matched Study of Prenatal Crack/Cocaine Use: II. Interactive and Dose Effects on Neurobehavioral Assessment. Pediatrics, 101(2), 237-241. Additional readings II Jacobson, J. L., & Jacobson, S. W. (1995). Strategies for detecting the effects of prenatal drug exposure: Lessons from research on alcohol. In M. Lewis & M. Bendersky (Eds.), Mothers, babies, and cocaine: The role of toxins in development. (1 ed., pp. 111-128). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence, Erlbaum Associates, Publisher. Jacobson, J. L., & Jacobson, S. W. (1996). Methodological considerations in behavioral toxicology in infants and children. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 390-403. Jacobson, J. L., Jacobson, S. W., Sokol, R. J., Martier, S. S., & Ager, J. W. (1993). Prenatal alcohol exposure and infant information processing ability. Child Development, 64, 1706-1721. Jacobson, J. L., Jacobson, S. W., Sokol, R. J., Martier, S. S., & Kaplan-Estrin, M. G. (1993). Teratogenic effects of alcohol on infant development. Alcoholism: Clinical and experimental research, 17(1), 174-183. Jacobson, S. W., Fein, G. G., Jacobson, J. L., Schwartz, P. M., & Dowler, J. K. (1984). Neonatal correlates of prenatal exposure to smoking, caffine and alcohol. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 253-265. Jacobson, S. W., Jacobson, J. L., Sokol, R. J., Martier, S. S., & Chiodo, L. M. Messinger (1996). New evidence for neurobehavioral effects of in utero cocaine Additional readings III Messinger Lester, B. M., Boukydis, C. F. Z., & Twomey, J. E. (2000). Maternal substance abuse and child outcome. In C. H. Zeanah, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health (pp. 161-175). New York, NY: Guilford. Lester, B. M., Freier, K., & LaGasse, L. (1995). Prenatal cocaine exposure and child outcome: What do we really know? In M. Lewis & M. Bendersky (Eds.), Mothers, babies, and cocaine: The role of toxins in development. (1 ed., pp. 19-39). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mayes, L. C., Bornstein, M. H., Chawarska, K., & Granger, R. H. (1995). Information processing and development assessments in 3-month-old infants exposed prenatally to cocaine. Pediatrics, 95(4), 539-545. Mayes, L. C., Granger, R. H., Frank, M. A., Schottenfeld, R., & Bornstein, M. H. (1993). Neurobehavioral profiles of neonates exposed to cocaine prenatally. Pediatrics, 91(4), 778-783. Mayes, L. C. F., Thomas. (2001). Prenatal drug exposure and cognitive development. In R. J. Sternberg & E. L. Grigorenko (Eds.), Environmental effects on cognitive abilities (pp. 189-219). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Singer, L. T., Arendt, R., Minnes, S., Farkas, K., Salvator, A., Kirchner, L., & Kliegman, R. (2002). Cognitive and Motor Outcomes of Cocaine-Exposed Infants. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(5), 1952-1960. Singer, L. T., Arendt, R., Minnes, S., Salvator, A., Siegel, A. C., & Lewis, B. A. (2001). Developing language skills of cocaine-exposed infants. Pediatrics, 107(5), 1057-1064. Tronick, E. Z., Frank, D. H., Cabral, H., Mirochnick, M., & Zuckerman, B. (1996). Late doseresponse effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on newborn neurobehavioral performance. Pediatrics, 98(1), 76-83.