the Case Studies Handout

advertisement

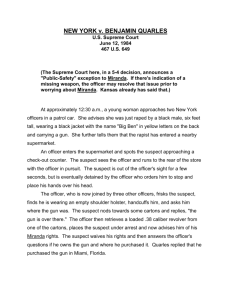

INSIGHTS ON LAW & SOCIETY Vol. 16, No. 1. Fall 2015 Looking at Miranda: Your Right to Remain Silent Case Studies Handout Greenwald v. Wisconsin (1968) Facts: A man was arrested on suspicion of burglary and was taken to a police station at 10:45 pm. He was suffering from high blood pressure, a condition for which he was taking medication twice a day. The suspect had last taken food and medication seven hours prior to his arrest and did not have medication with him at the time of the arrest. At the police station, the suspect was interrogated for one hour and fifteen minutes. He was not advised of his constitutional rights, he repeatedly denied guilt, and made no incriminating statements. He was interrogated the following morning by several officers and was not offered food or access to his medication. During this time he refused to answer questions and only spoke to deny his guilt. The suspect was asked to write out a confession and he refused stating that "it was against my constitutional rights" and that he was "entitled to have a lawyer." These statements were ignored and after more than two hours of interrogation petitioner began a series of oral admissions, culminating in a confession that was put into writing. At 1:00 p.m., he was advised of his constitutional rights. According to his testimony, he confessed because "I knew they weren't going to leave me alone until I did." Before trial, the suspect requested a hearing on the voluntariness of certain oral admissions and a written confession he had given while in police custody Questions before the U.S. Supreme Court: Was petitioner’s confession voluntary and was his right to counsel denied? Court Ruling: In a 6-3 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that on the "totality of the circumstances" surrounding petitioner's inculpatory statements that were admitted into evidence at the trial, which resulted in his convictions, such statements were not voluntary. Petitioner was not given counsel, despite his remarks that he was “entitled” to counsel he was also without food, sleep, medication, and was not given adequate warnings as to constitutional rights. “Considering the totality of these circumstances, we do not think it credible that petitioner’s statements were the product of his free and rational choice.” Questions: 1. Was petitioner in custody when he was interrogated in this case? 2. What does the Court mean by “totality of circumstances”? Do you agree with this reasoning? Rhode Island v. Innis (1980) Facts: After a picture identification by the victim of a robbery, Thomas J. Innis was arrested by police in Providence, Rhode Island. Mr. Innis was unarmed when arrested. He was advised of his Miranda rights and subsequently requested to speak with a lawyer. While escorting Mr. Innis to the station in a police car, three officers began discussing the shotgun involved in the robbery. One of the officers commented that there was a school for handicapped children in the area and that if one of the students found the weapon he might injure himself. Mr. Innis then interrupted and told the officers to turn the car around so he could show them where the gun was located. Question before the U.S. Supreme Court Did the conversation between the officers in front of Innis constitute as interrogation as defined in Miranda v. Arizona? Court Ruling: In a 6-to-3 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Miranda safeguards came into play "whenever a person in custody is subjected to either express questioning or its functional equivalent," noting that the term "interrogation" under Miranda included "any words or actions on the part of the police (other than those normally attendant to arrest and custody) that the police should know are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response from the subject." The Court then found that the officers' conversation did not qualify as words or actions that they should have known were reasonably likely to elicit such a response from Innis. Questions: 1. Was Mr. Innis under custody when he told the officers where the gun was located? 2. The Court determined that Mr. Innis’s comments regarding the gun were voluntary, how might the Court have ruled if Mr. Innis’s comments were in response to a question from one of the officers regarding the whereabouts of the gun? 3. What significant definition did the Court establish in its ruling? New York v. Quarles (1984) Facts: After receiving the description of Mr. Quarles, an alleged assailant, a police officer entered a supermarket, spotted him, and ordered him to stop. Mr. Quarles stopped and was frisked by the officer. Upon detecting an empty shoulder holster, the officer asked Mr. Quarles where his gun was. Mr. Quarles responded that “the gun is over there,” and the officer retrieved it, arrested Mr. Quarles and gave him his Miranda warnings. The trial court suppressed Mr. Quarles’s statement and the state appellate courts affirmed. Question before the U.S. Supreme Court: Is there an exception to the requirement that a suspect be read their Miranda rights before their answers can be admitted into evidence when the officer’s aims in questioning are to insure that no danger to the public results from concealment of a weapon? Does the Constitution require an officer to tell a suspect of his Miranda rights before asking questions? Court Ruling: In a 5-4 decision the U.S. Supreme Court held that there is a "public safety" exception to the requirement that officers issue Miranda warnings to suspects. Since the police officer's request for the location of the gun was prompted by an immediate interest in assuring that it did not injure an innocent bystander or fall into the hands of a potential accomplice to Mr. Quarles, his failure to read the Miranda warning did not violate the Constitution. Questions: 1. Why doesn’t Miranda apply in this case? 2. In what other circumstances might the “public safety” exception apply? Howes v. Fields (2011) Facts: During Randall Fields incarceration, law enforcement officers who did not work for the prison questioned him regarding activities unrelated to his incarceration. Mr. Fields made incriminating statements to the officers and was convicted. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit granted Mr. Fields's petition for habeas corpus relief, holding that the state court decision was in conflict with clearly established Supreme Court precedent forbidding the admission of statements made without the protection of Miranda warnings. Questions before the U.S. Supreme Court: Did the state court make a mistake in admitting the statements Mr. Fields made without the benefit of Miranda warnings, while he was sequestered from the general prison population and questioned? Court Ruling: In a 6-3 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that investigators don't have to read Miranda rights to inmates during jailhouse interrogations about crimes unrelated to their current incarceration. "Imprisonment alone is not enough to create a custodial situation within the meaning of Miranda." Questions: 1. Did the Court consider Mr. Field’s to be in custody when he was questioned by police? Why do you think the Court made this determination? 2. Do you agree with the Court’s interpretation of custody in this case?