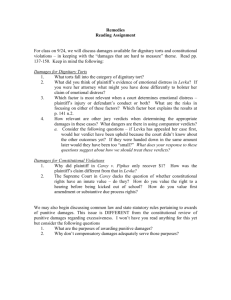

Contract Law 13 PowerPoint

advertisement

REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT - damages specific performance injunctions agreed sum quantum meruit 3 types of damages General damages Special damages Nominal damages Robinson v Harman 1848 ‘The rule of the common law is, that where a party sustains a loss by reason of a breach of contract, he is, so far as money can do it, to be placed in the same situation, with respect to damages, as if the contract had been performed.’ Damages may be recoverable for the following types of loss i. financial ii. physical inconvenience or discomfort iii. distress or annoyance caused directly by the physical loss caused by the breach iv.disappointment or distress where the sole or important object of the contract was to provide enjoyment, peace of mind or to prevent distress v. loss of reputation vi.loss of opportunity where not too speculative to calculate damages on the expectation basis How to ‘quantify’ the amount of damages • Diminution in value method or • Cost of cure (re-instatement) method or • Consumer surplus method Relevant factors when quantifying damages i. whether the innocent party has attempted to ‘mitigate’ his loss. ii. whether the loss in question was actually ‘caused’ by the breach of contract. iii. the issue of ‘remoteness’ of the loss from the breach. Addis v Gramophone Co Ltd 1909 This case has been taken as authority for the proposition that damages are not recoverable for disappointment, hurt feelings, loss of reputation or distress caused by the breach. However, since this case a series of ‘exceptions’ have developed to allow recovery of damages for loss which may not be seen as purely financial. Loss of reputation Malik v Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA 1998 Aerial Advertising Co v Batchelors Peas Ltd (Manchester) 1938 Substantial ‘physical inconvenience or discomfort’ Hobbs v L & S W Railway 1875 Bailey v Bullock 1950 Watts v Morrow 1991 Watts v Morrow 1991 Mr and Mrs Watts employed Mr Ralph Morrow FRICS a surveyor to survey the house for them. He reported that the house would not need any major repairs, something Mr and Mrs Watts wished to avoid at all costs. On the basis of this report they put in an offer of £177,500 and were successful. They soon discovered that the house needed lots of substantial repairs so sued the surveyor for breach of contract for the negligent survey. Trial judge’s assessment of damages On pure financial loss, the trial judge used the cost of cure approach and awarded special damages of £33,961.35 – the cost of the repairs For distress and inconvenience, he awarded them what he called ‘modest’ damages of £4000 each under this head ie. £8000. Ralph Gibson LJ on damages His Lordship concluded, after a survey of leading cases re surveys negligently performed, that the amount of damages for financial loss should be calculated on the diminution in value basis ie. £15,000 plus interest. He also said that damages were only recoverable for ‘distress caused by the physical consequences of the breach’ - not available for distress per se. Thus, he awarded them the modest sum of £750 general damages under this head, plus interest at 15%. Points raised in the case i. the 2 main heads of damages at work ii. the interplay between cost of cure and diminution in value iii. the approach to physical discomfort and distress caused by physical discomfort iv. the link between breach of contract and what physical discomfort the breach ‘caused’ v. mitigation points – that it is based on reasonableness – vi. vi. that in this case they did not succeed in getting damages for pure distress because this was not seen by his lordship as part of the surveying contract, either expressly or by implication. Jarvis v Swan Tours Ltd 1973 In this case the plaintiff booked a 2 week Christmas skiing holiday for £63.45. The court held that there was a breach of contract and that he was entitled to be compensated for his disappointment and distress for the loss of his holiday and loss of facilities that had been promised in the brochure. He was awarded the amount he had paid for this holiday, financial loss, plus an additional £60 to compensate him for his disappointment. Knott v Bolton 1995 Originally, this ability to be awarded damages for disappointment per se, only applied where the ‘sole object’ of the contract was to provide enjoyment, peace of mind or prevent distress. Thus, in Knott v Bolton 1995 a contract with an architect to design a house for a couple who contemplated that it would be their ‘dream home’ did not qualify. Farley v Skinner 2001 In this case the claimant who was starting his retirement had employed a surveyor to survey a house he intended to buy and to report, inter alia, whether the house would be affected by aircraft noise. He said it would not be affected, but it was. The House of Lords held that the claimant was entitled to damages for the significant interference with his enjoyment of the property caused by the noise. Lord Steyn Counsel for the defendant had argued that the plaintiff could only succeed if the sole object of the contract had been for pleasure. Lord Steyn noted that their argument was strengthened by Knott v Bolton, but stated that: ‘It is sufficient if a major or important object of the contract is to give pleasure, relaxation or peace of mind. In my view, Knott v Bolton was wrongly decided and should be overruled.’ Ruxley Electronics and Construction Ltd v Forsyth 1994. In the House of Lords, Lord Mustill said that there were not 2 alternative measures of damages, cost of cure or diminution in value. Rather, he said that there was one, the true loss suffered by the claimant. He said that although quite often in commercial contracts the loss to the claimant is clearly ‘pecuniary’, in consumer contracts quite often the loss to the claimant is difficult to see in monetary terms. This was because the loss may be manifested in non-monetary terms such as pleasure, which is by definition subjective. This is what is known as the ‘Consumer Surplus’. Diesen v Samson 1970 In this Scottish case, the Sheriff stated that in ‘non-commercial’ contracts, if the court thinks injured feelings were in the contemplation of the parties in the event of breach of contract, then damages could be awarded. Clearly in this case, it must have been in the contemplation of both parties that if the photographer did not turn up then the bride would have injured feelings if she had no photographs of her wedding day. As such a moderate sum of £30 was awarded in damages. McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission 1951 The High Court in Australia said that it would be too speculative to try to assess expectation loss in terms of lost profit since the contract had not detailed the size of the tanker or how much oil it still contained. So instead the court awarded ‘reliance’ loss damages – the expenses the plaintiff had incurred in going to search for the tanker. In addition, they awarded damages based on the ‘restitutionary interest’. Working out expectation damages Chaplin v Hicks 1911 and Allied Maples Group Ltd v Simmons & Simmons 1995 A case on causation C & P Haulage v Middleton 1983 Cases on restitutionary damages Surrey County Council v Bredero Homes Ltd 1993 Attorney General v Blake 1998 Cases on remoteness of damage The key cases here are: Hadley v Baxendale 1854 and Victoria Laundry v Newman Industries Ltd 1949. Specific performance, injunctions, agreed sum and quantum meruit shall be discussed in a separate lecture.