Contracts I-Wilmarth – Fall 2012

advertisement

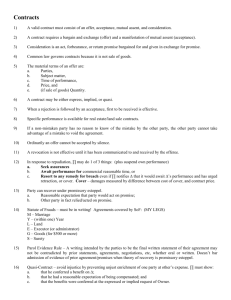

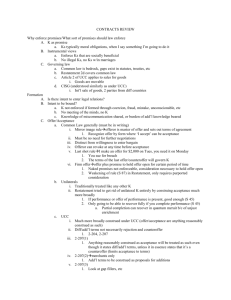

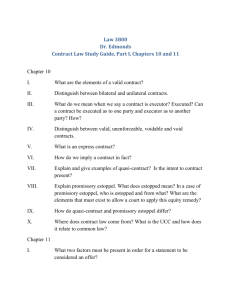

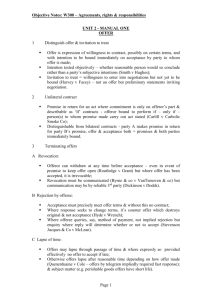

Contracts I Outline – 44 Pages of Death Wilmarth, Fall 2012 1. 2. 3. DEFINITIONS a. Express Contract – agreement manifested in words b. Implied-In-Fact Contract – agreement manifested by conduct c. Unilateral Contract: results from an offer that expressly required performance as the only method of acceptance i. Acceptance: rending performance or promise of performance ii. § 45: Substantial part performance renders K irrevocable iii. UCC: § 2-206(2): If offeree begins or completes performance, may need to notify offeror within reasonable amount of time if offeror would not know about performance iv. If offeror is not sure whether he wants promise (bilateral) or performance (unilateral) in return, offeree can choose (§ 32) v. Peterson v. Pattberg: Mortgage owner D makes offer to P mortgage holder that if P pays next interest and remained of balance by certain date, then over; P walks to his house but D revokes before P can give him the money 1. Court: Revoked before performance so no K vi. Cook v. Coldwell Banker: P sues b/c D promised bonus from Jan 1 to Dec 1, then says they will pay in March following year; P leaves in Jan and D refuses to pay 1. Court: Unilateral offer inducing agent to remain; D did not revoke first offer by making second offer because agent substantially performed on original offer d. Bilateral Contract: offers for other methods of acceptance i. Unless a reward, prize or contest; or expressly requires performance for acceptance e. Merchants (UCC § 2-104): Those who regularly deal in goods of the kind sold, or who otherwise hold themselves out as having special knowledge or skills as to the practices or goods involved. i. Dealer: deals in goods of the kind (regularly buys/sells) ii. Expert: holds self out as having knowledge or skill IS THE CONTRACT PREDIMOMINANTLY FOR GOODS OR SERVICES? a. Services & Real Estate: Common Law b. Sale of Goods: Article 2 of the UCC (§ 2-103) i. Consumer & Commercial Transactions in goods ii. Goods are movable, tangible property iii. Does not cover patents, trademarks or other IP iv. Goods fixed to real estate are not goods in UCC c. Mixed Contracts Look to: i. Language of Contract ii. Nature of business of supplier iii. Intrinsic worth of materials iv. Nature of breach to determine if transaction mainly for goods or services v. Jannusch v. Naffziger: P sells food truck, equipment, food, etc to D; D uses business as own, made income, paid taxes then unhappy with performance so tries to return it to P 1. Court: Under § 2-204, contract made in any manner sufficient to show agreement of parties of contract even if terms are left open, etc; Conduct looks like sale of a business d. If Contract Divides Payment, apply UCC to sale of goods part and common law to the rest IS THERE A CONTRACT? a. Formation of a Contract i. First, look for agreement 1 b. 1. The initial communication – was it an offer? 2. What happens after initial communication – was the offer terminated? 3. Who responds and how – was there acceptance? ii. Next, determine whether the agreement is legally enforceable 1. Ray v. William G. Eurice, Inc: P homeowner sues D contractor for breach of K when D refused to build according to specs drafted by P where specs different between both parties but both signed the K with P’s specs a. Court: Parties to a K bound by what they sign; unilateral mistake not a defense 2. Lucy v. Zemmer: two guys drunk at bar, make K for purchase of land, enforced because of past dealings and friendship; D thought P was just joking and refused to sell a. Court: K upheld because they made valid K 3. Skirbina v. Fleming: P mechanic sues for wrongful termination but signed document barring claims from termination a. Court: P held accountable because he willingly signed; should have read the K 4. Leonard v. Pepsico: P sues for private plane because D advertised 7 million pepsi points can get the plane a. Court: No reasonable person would understand jet plane offered as premium for soft drinks OFFER i. Restatement (Second) § 24: An offer is the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it. 1. Communication by offeror 2. Creating reasonable expectation in offeree that offeror will enter into contract ii. Content Requirements 1. Common Law: Price & Description Required 2. UCC: Quantity & Intent to be Bound a. UCC § 2-204 (Formation in General) i. May be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement (including offer & acceptance; conduct by both parties which recognizes existence of K) ii. K may be found even though moment of making it is undefined/undetermined iii. Even though one or more terms are left open, K for sale does not fail for indefiniteness if: 1. Parties intended to make the K 2. Reasonably certain basis for giving appropriate remedy iii. Insufficient Offers 1. Preliminary Negotiations are not an offer if the person to whom its addressed knows or has reason to know that the person making it does not intend to conclude a bargain until he has made a further manifestation of assent (Restatement (Second) § 26) 2. Advertisements are not ordinarily intended or understood as offers to sell. a. Offers by advertisement to the general public must ordinarily be some language of commitment or some invitation to take action without further communication. b. Izadi v. Machado: Ad says buy any new ford and get $3000 minimum trade in allowance for any new vehicle and places in 2 small print that’s hardly noticeable “toward purchase of new aerostar or turbo t bird” i. Court: Terms definite under § 24; Hinges on when a company uses intentionally misplaced words to create belief in ordinary reasonable reader that they have no intention of upholding, this is an offer (bait & switch) 3. Quotation of price is usually not an offer unless it contains the essential terms of the agreement 4. Invitation of bids or other offers is not an offer but rather an invitation for the other person to make an offer a. Lonergan v. Scolnick: P wants to buy land advertised by D in paper; P mails inquiry and D sends back form letter with description of property and told to respond soon because other offers are available; D Sells to someone else, P receives notice and then sends acceptance 3 days later i. Court: offer not present because form letter not meant to be binding 5. Recital: mere recital of work “offer” not enough 6. Bid: putting contract out for bid not an offer iv. Termination of Offers: offer cant be accepted if terminated (§ 36) 1. Rejection or Counter-Offer by Offeree a. Rejection: Offeree’s power of acceptance terminated by his rejection of offer; manifestation of intention not to accept offer is a rejection (§ 38) i. Effected when received by offeror, not dispatched b. Counter-Offer: counter offer terminates the offer and becomes a new offer (§ 39) i. No contract unless counteroffer has been accepted by original offeror ii. Counter-offers do not terminate option contracts! iii. Normile v. Miller: Seller D made offer with time limit and buyer P counter-offered with changes; P tried to accept after notice of revocation and within time limit of accepting original offer, but time limit meaningless after counter offer made new offer, so revocation valid once notice given to P 1. Court: counter offer with material change terminates original offer and give original offeror power of acceptance 2. Lapse of Time (§ 41) a. Time specified in offer or if silent, at the end of reasonable time 3. Revocation by Offeror a. Terminated when offeree receives from offeror manifestation of an intention not to enter into K (§ 42) b. Terminated when offeror takes definite action inconsistent with intention to enter into K and offeree acquires reliable info to that effect (§ 43) c. Offers made by ad or newspaper to public or number of unknown people terminated when stated publically by advertisement or newspaper (§ 46) 4. Death or Incapacity of either Party (§ 48) a. Death or incapacity of either party after offer but before acceptance terminates the offer b. Exception: Irrevocable Offers (Option Contracts) 3 v. Irrevocable Offers (Option Contracts, Firm Offers, General Contractor & Subcontractor cases, Unilateral K Part Performance) 1. Common Law – Option Contract a. An offer cannot be revoked if the offeror has made an offer and also: i. Promised not to revoke or promised to keep the offer “open” and; ii. The promise is supported by payment or other consideration b. Offer remains irrevocable for period of time specified, once expired it’s revocable c. If offeror should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance of substantial character by offeree before acceptance and this indeed happens, then binding as option contract d. Berryman v. Kmoch: Parties enter into K where landowner gives option to purchase land at agreed price for 120 days for $10 consideration; consideration never paid but party lines up investors; Landowner asks to be released and without agreement from other party sells to 3rd party during the period; Other party tries to buy land afterwards i. Court: failed to pay consideration so no option K; knew that landowner took action different from the proposed contract (selling to third party under RS 43) so offer was terminated 1. No promissory estoppel because didn’t rely to his detriment in substantial way and land owner couldn’t reasonably foresee or expect reliance when he made the promise 2. UCC – Firm Offer Rule (UCC § 2-205) a. An offer cannot be revoked for up to three months if: i. Offer is to buy or sell goods; ii. Signed, written promise to keep the offer open; and iii. Party (Offeror) is a merchant (merchant generally person in business of any kind) b. No payment required c. Time period is up to three months; can be less i. Can be extended through renewal or if consideration is given 3. GC & SC Cases: Detrimental Reliance a. An offer cannot be revoked if there has been: i. Reliance that is ii. Reasonably foreseeable, and iii. Detrimental b. OLD VIEW: James Baird Co v. Gimbel Bros: D subcontractor sent P general contractor offer to supply material for job; D did not realize mistaken about total quantity of material needed; P received offer and big on job same day basing bid on quote provided by D; Same day D realized mistake and telegraphed withdrawal; P accepts offer several days after receiving confirmation of withdrawal i. Court: No K Offer was withdrawn before accepted (acceptance was too late); using the bid isn’t accepting it unless you notify of acceptance; SC wouldn’t enter into one sided deal that allowed for 4 4. c. GC to just accept whenever they want without being able to revoke c. NEW VIEW: Drennan v. Star Paving Co: P GC prepped bid for school district; D SC was lowest bidder and P used this bid in computing his own bid; Industry custom that lowest bid will win and D had reason to now his lowest would be relied upon to P’s detriment; day after receiving bid P stops by D’s office where P was informed D’s bid was mistake i. Court: found for P since loss resulting from mistake fell upon party who caused it; P had no reason to believe D’s bid was in error and P entitled to rely on it ii. Majority of Jurisdictions RELY ON DRENNAN ANALYSIS (§ 87 Adopts Rule to apply to cases where there has been substantial and reasonably forseeable reliance on offer before acceptance) d. Inequitable conduct by the general contractor may preclude use of promissory estoppel: i. Bid Shopping – trying to find another SC who will do the work more cheaply while continuing to claim original bidder is bound ii. Bid Chopping – attempt to renegotiate with the bidder to reduce price Part Performance: The start of performance pursuant to an offer to enter into a unilateral contract makes the offer irrevocable for a reasonable time to complete performance a. R §45: Beginning performance or tendering a beginning is enough ACCEPTANCE i. Fact Patterns 1. Offeree Starts to Perform a. Start of performance is acceptance implied promise to perform a bilateral contract b. Exception: Start of performance is not acceptance of unilateral contract offers, completion of performance required 2. Distance & Delay in Communications (Mailbox Rule) a. Acceptance made in same manner & medium as offer is operative as soon as put out of Offeree’s possession (§63) i. Acceptance under option contract not operative until received by offeror b. Medium of acceptance must be reasonable in circumstances (mail generally accepted) (§ 65) c. Mailbox rule only applies where acceptance property stamped, addressed, etc. (§ 66) 3. Conditional Acceptance terminates the offer a. Look for: “accept” followed by “if, only if, provided, so long as, but, on condition that”, etc. b. Common Law: Conditional acceptance rejects and replaces the offer; silence by original offeror accepts the new conditions c. UCC: Conditional acceptance rejects and does not replace the offer 4. Additional Terms To Contract With Acceptance a. Common Law Mirror Image Rule: response to an offer that adds new terms is treated like counter offer rather than acceptance (No Contract!) 5 5. i. Last Shot Rule: Performance by both parties becomes acceptance of counter offer ii. Princess Cruises v. General Electric: P enters into K with GE for inspection and repair of ship (predominant purpose of K is services, not goods); P sends purchase order w/terms, D sends acceptance with different terms; parties pay no attention to specific conditions 1. Court: can only award damages consistent with the terms and conditions of the counter offer by D b/c of last shot rule and no mirror image here b. UCC Additional Terms Still Acceptance under § 2-207 i. Fact Pattern: Offer to buy goods with response with additional terms ii. There is K if there’s expression of acceptance or written confirmation iii. Additional term becomes a part of the contract only if: 1. Both parties are merchants; and 2. (A)Offer doesn’t limit acceptance to terms of offer; (B) Additional term is not “material” (A fact question); (C) Notification of objection to term has not be given or within reasonable time; and 3. Offeror does not object to the additional term iv. There is also K if there is performance and conduct that shows there was a K made v. Some Jurisdictions say no more “Last Shot Rule” § 2-206 & 2-207 match up forms and where they agree, agreement is applied; where they don’t agree, Knock Out Rule applies so those terms don’t count unless manifest agreement through conduct or oral statements, or otherwise covered by the code vi. Brown Machine v. Hercules: D buys equipment from P; employee of D injured using it and sues D; P sues D for indemnification stating acceptance form they sent after purchase contained the clause; P says they didn’t agree 1. Court: terms materially altered the agreement and not expressly accepted by D so no K Electronic Contracting Acceptances a. Clickwrap Contracts i. Agreement appears on webpage and requires user consent to terms and conditions by scrolling and clicking I agree 1. Usually software, services, or tangible products ii. Clickwrap agreements are considered writings because they are printable and storable iii. Courts apply traditional principles, focus on whether P had reasonable notice and manifested assent to the agreement 6 b. c. iv. Failure to read an enforceable clickwrap agreement will not excuse compliance with its terms v. Feldman v. Google: P sued D over agreement made for online ads and recovery from fraud clicks; clickwrap agreement included forum selection for disputes to be heard in CA; P says didn’t see it; A bottom of agreement that he was supposed to read before hitting accept 1. Court: there was reasonable notice and mutual assent because it stated for him to read the terms and reasonably prudent person would have known of existence of terms; P hit accept willingly Shrinkwrap Terms i. Purchaser orders a product. When P receives product, it is wrapped in plastic, contains warning that opening plastic and using product constitutes agreement to the term contained. Purchaser has an opportunity to inspect product and terms, P may return product if unhappy. If don’t return, agree to terms. ii. ProCD (Majority) Rule: When purchaser places order, vendor is the one making the offer by shipping product with terms & conditions included; If vendor states that purchaser accepts offer by retaining product for certain amount of time, purchaser bound by terms if he does not return the product within the time period. Purchasers are not bound until they receive the product and terms, inspect them and decide whether or not to keep the product. iii. Kleock (Minority) Rule: Purchaser makes offer and shrinkwrap terms are proposals for additions to contract governed by UCC § 2-207(2). Purchasers bound when vendor accepts payment. 1. If between consumer and merchant seller, merchant terms not part of contract unless agreed to by customer 2. If between two merchants, terms not part of contract if any of three situations in 2-207(2) apply iv. Defontes v. Dell: P alleges D’s collection of taxes on optional service is wrong; D’s terms say mater should be arbitrated due to terms on hyperlink on website (browsewrap) sent to P after placing order and were shrinkwrapped to product when received 1. Court: Followed ProCD and said K formed when customer received the product; also not reasonably apparent that P could reject terms by returning the product because too many elements ambiguous; Reasonable person would not have understood how to reject by returning the product Browsewrap Terms i. Different from clickwrap because terms are available on the website, but one is not required to scroll 7 ii. iii. iv. v. through them, and no agreement button is required to proceed Does not require user to manifest assent to terms expressly, party simply gives assent by using website To be valid, notice of terms must be easily visible and accessible Test to show browsewrap enforceable: 1. User provided adequate notice of existence of terms 2. User has meaningful opportunity to review terms 3. User provided adequate notice that taking specified action manifests assent to the terms 4. User takes action specified above Hines v. Overstock: P purchased product form D online; P returned it to D for $30 restocking fee; P claimed never saw terms for fee and that D never disclosed these costs; D says entering site required agreement of terms of mandatory arbitration in Salt Lake City due to terms and conditions of site; P said never made aware of these terms and was not required to view them as they were hidden somewhere on the site 1. Court: D did not show that P had notice of the terms; Link was hidden on website 6. Authority to Contract a. AGENCY?!?!?!?!?! 4. IS THERE VALID CONSIDERATION? IF NOT, PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL & RESTITUTION MAY PROVIDE LEGAL REMEDY! a. CONSIDERATION i. Benefit/Detriment Test: 1. Either detriment to promisee or benefit to promisor: a. Detriment party is left poorer somehow i. Relinquishment of legal right ii. Could be beneficial in other ways iii. Sufficient Consideration: Act, forbearance, or partial/complete abandonment of an intangible right or promise to do any of the above iv. Non-illusory promise (ie. promie to pay cash for promise to convey land) b. Benefit i. Usually mirror image of detriment ii. You got whatever you bargained for c. Bargain Theory (§ 17) Consideration must product of bargain; nothing is consideration if not so regarded by both parties ii. What Does Consideration Consist Of? (§ 71) 1. A performance or a return promise must be bargained for 2. A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise 3. The performance may consist of: a. An act other than a promise, or b. A forbearance, or 8 c. The creation, modification or destruction of a legal relation Comment C: A gift is not ordinarily treated as a bargain, and a promise to make a gift is not made a bargain by the promise of the prospective donee to accept the gift or by his acceptance of part of it. 5. Baehr v. Penn-O-Tex Oil: P sued for failure to pay rent after D took over accounting of Kemp’s operation of P’s filling stations, alleging K formed; D promised payment and P asserts forbearance to sue was consideration a. Court: no consideration because forbearance to sue was not induce by the promise to pay so no bargained for exchange iii. Adequacy of Consideration DOES NOT take into account EQUIVALANCE in VALUE (§ 79) Inadequacy of consideration won’t void a contract (no requirement in equivalence of value) 1. Batsakis v. Demotsis: P in Greece needs money that D lent her until she could reach her assets in USA; P promised to pay back $2000 for 500,000 drachmae and P argues contract unenforceable because drachmae only worth $25 a. Court: unequal consideration immaterial to enforceability of contract because P got what she bargained for iv. Insufficient Consideration 1. Illusory promises (§ 77) a. Performance entirely optional with the promisor 2. Past Consideration (no future obligation) a. Moral Obligation not consideration (moral duty arising out of past service or benefit) 3. Gifts donative, charitable, gratuitous, executory (in the future), testamentary (upon death) a. Dougherty v. Salt: P received promissory note from aunt because he was a good boy payable at death for value received i. Court: unenforceable gift because promise neither offered or accepted anything new for the Aunt and thus no consideration b. Exceptions: i. Executed Gift – delivered and accepted gift is irrevocable; no existing K or promise ii. Trust – gift set up in trust (money set aside) is enforceable iii. Mix – a combination of gift and bargained for exchange is sufficient consideration iv. Condition of Gift – Acts of benefit, not detriment, that are requested as consideration 1. Plowman v. Indian Refinery Co: P employees placed on retirement after economic downturn and provided with one half salary by semi-monthly checks; payments discontinued and P sues; no evidence of Board of Directors giving authority for this nor ratifying it afterwards a. Court: moral consideration and consideration for past performance do not count as valid consideration detriment of coming to office to pick up paychecks is condition of gift, not consideration 4. Token Consideration – impossible or totally worthless promise 4. 9 Pre-existing Duty (§ 73) legal duty or performance is already owed/obliged to the promisor 6. Intent action alone without intent to accept or knowledge of the offer 7. Motive motive or reason for a promise are not consideration for lack of detriment to other party v. Williston Rich Man & Tramp Example 1. Rich man offers Tramp coat for walking into store to select it; Tramp more benefitted by walk to store than detrimented; not consideration. Rich man also doesn’t get any meaningful benefit besides moral benefit. vi. CONSIDERATION IN FAMILY SETTINGS 1. Hamer v. Sidway: Uncle promises nephew money if he gives up drinking, tobacco, and other vice until he turns 21 a. Court: gave up legal right to do something and thus counts as legal detriment and thus consideration; benefits uncle because the nephew is healthier vii. CONSIDERATION IN COMMERCIAL SETTINGS 1. Pennsy Supply Inc. v. American Ash: D gives P aggrite for free to use as paving but cracks; substance toxic so expensive to remove; P sues because D wont pay for it a. Court: P provided consideration in that they took the aggrite from them so that D wouldn’t have to dispose of it themselves and D vise-versa 2. Cobaugh v. Klick-Lewis: P sees sign for Chevy Beretta free if hole in one and hits it D neglected to remove sign after tournament a. Court: enforceable consideration b/c P took shot he didn’t legally have to take; D gets publicity, goodwill and advertising from the sign 3. Marshall Durbin v. Baker: Baker given K that gives compensation after triggering of events due to company instability in return for staying with the company by then-CEO of company with 82% of shares (had authority) a. Court: enforceable consideration b/c Baker changed his behavior for them; didn’t work and stayed with the company PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL (Detrimental Reliance) (§ 90) i. FORUMULA: Promise + Reliance that is reasonable, detrimental, foreseeable + enforcement is necessary to avoid injustice ii. PROMISES WITHIN THE FAMILY 1. Kirksey v. Kirksey (before promissory estoppel times): P woman induced by D brother in law to move to his house after husband dies, D then kicks her out a. Court: no detrimental reliance, but strange context: 1845 and she’s a woman so no rights 2. Ricketts v. Scothorn: Grandfather D gives promissory note to granddaughter P for $2000 and 6% interest to enable P to quit job; D dies and executor won’t give her money a. Court: Grossly inequitable to permit D to resist payment on grounds because even though no consideration (voluntary gift), she relied on Ds money in that she quit her job (equitable estoppel b/c promissory estoppel not here yet) i. Certainly involves reliance (key element) ii. False statement of facts (misrepresentation) iii. Comes out of equity law not common law 3. Harvey v. Dow: Parents agree to transfer land to daughter, father allows daughter to build a house on the lot, daughter builds lot with 5. b. 10 insurance proceeds from death of her husband; parents then refuse to give her lot a. Court: promise and conduct of father induced reliance, detriment of losing time and all her money, only enforcing would do her justice remanded for new trial b/c not sure if they wanted to give her the whole lot 4. Greiner v. Greiner: mother made promise to give son land because he was disinherited from father’s will a. Court: Son in detrimental reliance moved from another part of state and took residence on land, exerted efforts improving the land, so PE available 5. Wright v. Newman: P sought child support for son & daughter from D where D knew was not father of son but put himself on birth certificate and for 10 years held himself as father unbeknownst to mother a. Court: mother relied on father for this whole time to her detriment for son and he knew he had legal responsibility to pay as a parent iii. CHARITABLE DONATIONS & PROMISES 1. Generally, Donative promise usually held unenforceable due to lack of consideration unless detrimentally relied upon a. Written promises are usually binding even without consideration b. Oral promises are usually non-binding unless there is consideration or detrimental reliance 2. Congregation v. DeLeo: Decedent makes oral promise to give P money for library; Administrator refused to give money to P a. Court: P’s allocation of money in budget didn’t constitute reliance; if they had made contract commitments for substantial building expenses that would be different 3. King v. Trustees of BU: MLK makes charitable pledge to D certain papers; P says papers belong to estate a. Court: MLK benefitted from D attending to his papers in turbulent times therefore this is sufficient consideration 4. Allegheny College v. National Chautaqua County Bank: Descendent promised to give P college money 30 days after death with condition scholarship established be named in her honor and donated $1000 prior to death a. Court: Detrimental reliance assumed by P by naming scholarship in her honor after receiving part of money was sufficient consideration 5. Woodmere v. Steinberg: Made pledge to academy for $200,000 but then moved kids and doesn’t want to pay a. Court: through public policy should be held accountable on promissory estoppel (charities have no bargaining power or legal recourse if they rely on donations); on consideration library named in honor of wife so he should be held to pay iv. PROMISES IN COMMERCIAL CONTEXT 1. Katz v. Danny Care: P former employee injured on job and D employer convinced him to quit and receive pension a. Court: employee retired in reliance of promise; decided to leave a position where he earned more money to accept lower payment 2. Feinburg v. Pfeiffer: D offered P to retire anytime she wants with pay of $200 every month for life; D stops paying, P sues a. Court: P detrimentally relied on promise to quit higher paying job and elect for lower amount of money 11 3. c. Pitts v. McGraw: D told P they retired him and then company said they’d give him percentage of sales but stopped a. Court: didn’t voluntarily retire so no PE 4. Hayes v. Plantations: P announces retirement to company then meets with officer of D who promises to take care of P a. Court: P announced decision to leave before promise made so no reliance and no PE 5. Pop’s Cones v. Resorts International: D resorts promises P a new location at their hotel and that they should leave their current location in reliance of this coming offer a. Court: Damages awarded to P b/c although no formal contract entered into, P suffered loss of prior location and ability to earn profits during the summer + fees of finding new location in reliance of resorts hotel space promise 6. Hoffman v. Red Owl: similar situation to Pop’s cones with the same outcome by court 7. Gruen Industries v. Biller: PE not allowed if business deal falls through and didn’t detrimentally rely on a promise RESTITUTION: (Restatement (Third) of Restitution § 1) i. Fact Pattern 1. A confers benefit to B where B should have known that A intended to be compensated 2. B unfairly enriched so he must give fair market value of benefit to A ii. Requirements: 1. Enrichment under the circumstances; and, 2. Retention of benefits would be unjust iii. Measure of Benefit 1. Fair market value of goods or services – Restatement § 371 (a) 2. Reasonable value to other party of what he received in terms of what it would have cost him to obtain it from a person in claimant’s position 3. This is the majority approach. 4. Ex. If Watts had taken this approach (which the money award actually reflects), Sue Watts would have been reimbursed for costs of housekeeping, child-care, etc. 5. Value Added – See R § 371 (b) – Extent to which other party’s property has been increased in value or his other interests have been advanced. a. Less common remedy – Specific facts and evidence must be shown. b. Watts v. Watts: Court gave her 10% of their accumulated wealth. iv. Protection of Another’s Life or Health (RS Restitution Third § 20) 1. A person who performs, supplies or obtains professional services required for the protection of another’s life or heath is entitled to restitution from the other as necessary to prevent unjust enrichment, if the circumstances justify the decision to intervene without request 2. Unjust enrichment under this section is measured by a reasonable value for the services in question 3. Credit Bureau v. Pelo: D hospitalized against will, involuntarily committed, refused to sign consent until forced to, DR.s inform him he has bipolar disorder a. Court: Unjust enrichment because doctors gave him beneficial information about his bipolar disorder and he should pay for it 12 4. v. vi. vii. viii. In re Estate of Crisan: patient unconscious when care rendered and dies without regaining consciousness a. Court: doctors recover because they tried Implied-In-Fact Contracts 1. Conduct implies actual contract – law implies promise to pay reasonable amount for services --assent is silent but still mutual assent 2. The services were carried out under such circumstances as to give the recipient reason to understand: a. That they were performed for him and not some other person; and, b. That they were not rendered gratuitously, but with the expectation of compensation; and, c. The services were actually beneficial 3. Remedies for implied-in-fact contracts and restitution: a. If it is an implied-in-fact K, look at what was promised; or, b. If it is a restitution/quasi-contract, look at the fair/reasonable market value of the things provided, or look at wealth enhancement. 1. Bloomgarden v. Coyer: P introduces D’s who develop waterfront property; no oral or written agreement; finders fee relies on theories of implied in fact K a. Court: no implied in fact (Court needs to find all of the elements of a contract to make an implied contract exist) or real K Implied-In-Law Contracts (Quasi-Contract/Legal Fiction) 1. Not based on finding of agreement. Law will imply obligation when needed for justice because of unjust enrichment. 2. Generally, in order to recover on a quasi-contractual claim, a plaintiff must show that a defendant was unjustly enriched at the plaintiff's expense, and that the circumstances were such that in good conscience the defendant should make restitution. Because quasi-contractual obligations rest upon equitable considerations, they do not arise when it would not be unfair for the recipient to keep the benefit without having to pay for it. Thus, to make out his case, it is not enough for the plaintiff to prove merely that he has conferred an advantage upon the defendant, but he must demonstrate that retention of the benefit without compensating the one who conferred it is unjustified. Protection of Another’s Property (RS Restitution Third § 21) 1. A person who takes effective action to protect another’s property from threatened harm is entitled to restitution from the other as necessary to prevent unjust enrichment if the circumstances justify the decision to intervene without request. Unrequested intervention is justified only when it is reasonable to assume the owner would wish the action performed. 2. Unjust enrichment under this section is measured by the loss avoided or by the reasonable charge for the services provided, whichever is less Unmarried Cohabitants (RS Restitution Third § 28) 1. If two persons have formerly lived together in a relationship resembling marriage, and if one of them owns a specific asset to which the other has made substantial, uncompensated contributions in the form of property or services, the person making such contributions ahs a claim in restitution against the owner as necessary to prevent unjust enrichment upon the dissolution of the relationship 13 2. 3. The rule of subsection 1 may be displaced, modified or supplemented by local domestic relations laws Watts v. Watts court implies some type of agreement because of the way they behaved and carried themselves out as married partners even though they aren’t married for 12 years; the obligation for prevention of unjust enrichment is implied by law in a sense regardless of how parties behave in a case a. Parties may raise claims based upon unjust enrichment following the termination of their relationships where one of the parties’ attempts to retain an unreasonable amount of the property acquired through the efforts of both. b. Unjust Enrichment claims are based upon 3 elements: i. ii. There is appreciation or knowledge of the benefit by iii. retain the benefit. Holding: A contract is not required for this type of claim; it is instead based on a moral ground that society has an interest in preventing this type of unjust enrichment. ix. Intra-Family Claims 1. General rule: Services rendered by family members to one another are presumed gratuitous, while services rendered between individuals who are not members of the same family are presumed to be for compensation; 2. Unless, if an adult moves out of home for purposes of caring for an elderly parent for a substantial period of time, presumption of gratuity can be overcome. a. This varies by jurisdiction b. Courts require proof by “clear and convincing evidence,” which is higher than the usual evidence standard of “preponderance of evidence” PROMISSORY RESTITUTION i. Fact Pattern 1. Recipient of services makes express promise to pay but only after benefits are received ii. Restatement § 86 (Material Benefit Rule) 1. A promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice. 2. However, a promise is not binding in the section above if: a. The promisor conferred the benefit as a gift (gratuitously), or for other reasons the promisee has not been unjustly enriched; or, b. To the extent that its value may be disproportionate to the benefit. iii. Debt Barred by SoF (§ 82) – A promise to pay a debt barred by the statute of limitations can be express or it can be implied from the conduct of the obligor. Could be enforced because the debt is a preexisting legal obligation. iv. Promise to Pay Indebtedness Discharged in Bankruptcy (§ 83) 1. If the promise is made after, or during, the bankruptcy proceedings, then it is binding. v. Mills v. Wyman: P provided board, nursing and care to D’s son over 18 years of age after returning from voyage at sea sick; after finished caring, D wrote letter promising to pay P for expenses c. d. 14 1. 5. Court: no consideration for promise to pay b/c services rendered before promise made and past consideration is not valid consideration; also no reliance because it was made after the fact a. If D’s son was a minor, may have been enforceable but D received no material benefit vi. Webb v. McGowin: P injured saving D’s life, can’t work; D promises to pay P $ every two weeks for remained of P’s life; D lived up to it until he died, then stops paying 1. Court: K enforceable because injury to P was legal consideration b/c promise was made in recognition of material benefit previously received HOW THE HELL TO INTERPRET A COMPLICATED CONTRACT a. 1) WHAT FORM GOVERNS? i. UCC: First Form ii. Common Law: Last Form iii. Oral Agreements: If parties come to oral agreement and send each other confirmations of the contract… 1. The terms are the terms in the oral contract 2. Any terms different from those of the oral contract are NOT part of the contract 3. Any new terms that agree in writing are part of the contract 4. Any new terms that are not in both confirmations are NOT part of the contract b. 2) WHO’S INTERPRETATION OF MEANING PREVAILS? i. Generally: PLAIN MEANING PREVAILS, but if not ascertainable… ii. Standards of Preference of Interpretation (Restatement (Second) § 203; UCC § 1-303 (The Big Three) 1. Express Terms a. Restatement (Second) § 201 i. If two parties mutually attach an uncommon meaning to a term, the term takes on the meaning the parties intended ii. If the parties attach different meanings to their contractual language, the agreement is to be interpreted in accordance with the meaning of party A if party B either knew or had reason to know of the meaning attached by the former and party A did not know of any other meaning attached by B iii. If a court concludes that the parties attached different meanings but neither party knew or had reason to know the meaning of the other, no agreement because no mutual assent b. Joyner v. Adams: P wanted all buildings completed by certain time for D to keep base lease; buildings not finished till later; P says D has to pay rent escalation for time; D says no, difference in meaning between what developed meant i. Court: had two completely different meanings and didn’t know of each others, no K c. RS § 203 (a) - Provides that, when interpreting an agreement, a court should prefer an interpretation that makes an agreement reasonable, lawful, and effective. d. RS § 204 – Recommends that, in situations where there is intent to be bound, or the degree of performance already rendered may cause rescission to be appropriate, the court should supply a term that is reasonable under the circumstances. 15 Frigaliment v. BNS Int’l Sales: disagreement over what the meaning of the word “chicken” was; P sent fowl, D wanted “young tender birds” i. Court: Buyer has burden to prove meaning of chicken was only young tender birds in order to make K valid and did not because court found chicken itself ambiguous, and P should not have expected D to sell the type of chicken they requested for less than market price and incur a loss. f. Restatement (Second) § 206 i. In choosing the reasonable meanings, courts prefer the meaning of the party who did not write the words rather than the party who did write them g. General Principles of Interpretation for Express Terms i. The meaning of a word in a series is affected by others in the same series/a word may be affected by its immediate context ii. A general term joined with a specific term is deemed to include only things that are like the specific one iii. If one or more specific terms are listed, without any general or inclusive terms attached, other specific items are excluded iv. An interpretation that makes a contract valid is preferred to one that makes it invalid v. If a written contract contains a word or phrase which is capable of two reasonable meanings, one which favors one party and the other which favors the other, the interpretation that will be preferred is the one which is less favorable to the party by whom the contract was drafted vi. A writing or writings that form part of the same transaction should be interpreted together as a whole vii. The principal apparent purpose of the parties is given great weight viii. If two provisions of a contract are inconsistent, and one is general enough to include the specific situation to which the other one speaks, the specific provision qualifies the general or is an exception to the general ix. Handwritten or typed provisions control printed provisions as they are likely more recent and more reliable expressions of intent x. If a public interest is affected by a contract, that interpretation or construction is preferred which favors the public interest 2. Course of Performance (UCC Big Three #1) a. Sequence of conduct between parties to a particular transaction 3. Course of Dealing (UCC Big Three #2) a. Sequence of conduct concerning previous transactions between parties to a particular transaction that can be used as understanding their expressions 4. Trade Custom & Usage (UCC Big Three #3) a. Practice regularly used in industry norms iii. WHEN THERE IS A STANDARDIZED AGREEMENT (§ 211) e. 16 1. 2. 3. 4. c. (1) When a party signs or manifests agreement to a writing, and has reason to believe that the form is standardized, he adopts it as an integrated agreement with respect to the terms included. (2) Interpreted whenever reasonable, without regard to knowledge or understanding of terms, (3) But, where other party has reason to believe that the party manifesting such assent would not do so if he knew that the writing contained a particular term, the term is not part of the agreement. This is really a good faith clause. C&J Fertilizer, Inc. v. Allied Mutual Insurance, Co.: -in to avoid inside job. Here, there was no external evidence but a safe was tampered with and it was clearly not an inside job. Π claims never understood language to mean “it needed to be external physical breakin” – agent had just told them evidence needed that it wasn’t inside job. This exclusion not up front when they signed. a. Court: holds policy to reasonable expectations of the policyholder over the express terms of the agreement. b. Example of an Adhesion Contract: half of states will adopt reasonableness expectations to insurance agreements; the other have will only apply when express terms eviscerate the terms of the policy. c. Dissent: Reasonable expectations don’t apply when the party had reason to know of the insurance company’s meaning. i. Under RS § 211, C&J would only have gone the not have accepted that meaning. ii. Many courts will follow § 206 instead (holding meaning to be what the party who didn’t write the document though). WILL PAROL EVIDENCE BE ALLOWED IN TO AID IN INTERPRETATION OF EXISTING TERMS? i. Rule operates to exclude evidence and applies to all agreements where a written K has been developed (RS § 210; UCC § 2-202) 1. Prevents a party from presenting extrinsic evidence that contradicts or adds to the written terms of a contract that appears to be whole. ii. Classical View (Willistonian) MINORITY 1. Question of integration must be determined from the four corners of the contract, excluding extrinsic evidence introduction 2. Some jurisdictions still adhere to this view 3. Example Case: Thompson v. Libby (1885) – Seller P sues buyer D for price of lumber not purchased. Buyer refused to buy because they had an oral agreement on quantity, though the written K reflected no such term. Court finds document (a letter) was fully integrated and excludes outside evidence of oral agreement. iii. Modern View (Corbin) MAJORITY 1. Questions to ask: a. Did the parties agree for the document to be final? b. If so, is it a complete or partial expression of the terms? c. What other evidence should be let in? i. To aid in interpretation of existing terms ii. To show that writing is or is not an integration iii. To establish that integration is complete or partial iv. To establish subsequent agreements or modifications v. To show that terms were product of illegality, fraud, duress, mistake, lack or consideration 17 2. What is Integration? a. RS § 210 i. Complete Integration: writing that is intended to be final and an exclusive expression of the agreement of both parties. ii. Partial Integration: writing that is intended to be final but is not complete, because it deals with some but not all aspects of the transaction. iii. (3) Whether an agreement is integrated completely or partially is a matter of law from the beginning action. b. UCC § 2-202 - Final Written Expression – Terms in writing which are intended by both parties as a final expression of their agreement, with respect to such terms; may not be contradicted by evidence of prior agreement or contemporaneous oral agreement. 3. Determining Integration: a. Notes from RS § 210: i. Comment B: A writing cannot of itself prove its own completeness, and a wide latitude must be allowed for inquiry into circumstances bearing on the intention of the parties. ii. Finding of integration depends on the actual intent of the parties, and the court should consider evidence as well as the writing in determining level of integration. iii. Merger clause is NOT determinative of complete integration. ** Rejection of Classical Theory b. Notes from UCC § 2-202 i. Just because something is final on some matters does not mean that it is final on all. ii. Doesn’t have to be ambiguous in order to introduce evidence of integration. c. NOTE to both: It takes a LOT to be fully integrated. iv. RULES FOR BRINGING IN PAROL EVIDENCE 1. Complete Integration: a. Common Law i. Contradictory terms cannot be introduced. (See § 215) ii. Consistent additional terms cannot be introduced. (See § 216) iii. Can always introduce evidence to explain. (See § 214) b. Under UCC § 2-202 (a) i. No evidence of contradictory or consistent terms may be introduced. ii. Can still introduce evidence to explain or supplement, by the Course of Performance, Course of Dealings, and Trade Usage 1. Unless such terms are carefully negated by the explicit language of the K. 2. Partial Integration: a. Common Law i. Contradictory terms cannot be introduced. (See § 215) 18 ii. Consistent additional terms can be introduced. (See § 216) iii. As always, evidence to explain may be introduced. (See § 214) b. Under UCC § 2-202 – Can be explained or supplemented by: i. (a) Evidence of Course of Performance, Course of Dealings, and Trade Usage; 1. Unless such terms are explicitly negated, as above. ii. (b) Evidence of consistent additional terms 1. Unless additional terms are such that, if they had been agreed upon, they would certainly have been included in the document. 3. Non-Integration (Wilmarth: “Pretty rare”) – allow everything. v. INTRODUCING EVIDENCE TO EXPLAIN MEANING a. Common Law i. § 214 (c): Evidence to explain meaning can always come in, even if the K is fully integrated 1. Only allow subjective (unusual) meaning of a term if both parties agree to that meaning. 2. Can come in to explain an objective ambiguity or provide a reasonable alternative meaning, but not for one subjective meaning of one side. ii. § 222 – Usage of Trade – Unless otherwise agreed, comes in for meaning, supplements, or qualifications to agreement, if parties have reason to know of that term in their trade. iii. § 223 – Course of Dealing – Unless otherwise agreed to, Course of Dealing gives meaning to, supplements, or qualifies the agreement. b. Under UCC i. § 2-202 – Terms may be explained by Course of Performance, Course of Dealing, or Trade Usage; aka The Big Three. 1. This tends to mean the Big Three always come in unless contradictory (as below) or they are expressly negated. a. Note: Boilerplate language negating all implied terms won’t hold. ii. Nanakuli v. Shell (Express Terms Contradicting Course of Performance, Course of Dealings, Trade Usage) 1. Facts: -term contracts to price protect; argued course of performance and trade usage by another 2. bids. Court allows trade usage in to contradict express terms delivery. a. Notes: This is a serious stretch of UCC; it ranks trade usage over 19 6. express terms Wilmarth: doesn’t like this; thinks they were matching precedent to choose their desired outcome b. Course of Performance might have modified the K, but court didn’t apply that argument; instead, they negated express terms. 3. Most courts allow implied terms when they don’t negate express terms. c. IF there are two reasonable interpretations/meanings, then evidence should come in, and then go to a jury. i. Taylor v. State Farm: P had K with D stating P would give up contractual claims against D. P sues D for bad faith tort claim. 1. Issue: Did meaning of “contractual claims” include a bad faith tort claim based on a contract, and whether the writing was ambiguous. 2. Court: ambiguous term, determines that writing is fully integrated, but allows interpretation of meaning because language that can be reasonably construed in multiple ways should go to the jury. WAS IT AN AGREEMENT TO AGREE OR WAS THERE A FORMAL CONTRACT CONTEMPLATED? a. Common Law i. Fact Pattern 1. Parties have reached agreement 2. No conflicting terms 3. Agreement is incomplete because either party has chosen to decide certain matters at later date (agreement to agree) 4. OR reached agreement on major provisions but expect a formal written contract (formal contract contemplated) ii. Classic View: If parties know essential term is missing, no contract (Agreement to Agree) iii. If parties left out an essential term but proof shows that parties intended to be bound, there may be a contract 1. § 33 terms must be reasonably certain to form a K iv. Modern View: RS § 204: When sufficiently defined as a K, and parties have not agreed with respect to a term essential to their rights and duties, a term which is reasonable may be supplied by the court. (Agreement to Agree) v. If one party reasonably believes a contract has been formed and the other party has reason to know this, there is a contract vi. Parties may create a contract to make a future contract but only if the first contract contains all of the essential terms or methods to ascertain the terms in the first contract vii. OLD: Walker v. Keith (Agreement to Agree): P signed 10 year lease with option to renew based on comparative business conditions; after 10 years couldn’t agree on fair price or what business conditions would make them be 1. Court: no K because no agreement to essential term viii. NEW: Oglebay v. Norton (Agreement to Agree) P shipper sought to enforce long term K with D steel producer for transport of iron to D’s manufacturing plants; said they would agree on rate for current season but couldn’t agree on fair pricing 20 1. b. Court: came up with fair price and enforced K even though no agreement to essential term because of longstanding relationship and detrimental reliance by shipping company due to their necessity to purchase more ships, etc.; supplied the reasonable price ix. R § 27 – Existence of a K where Written Memorial Contemplated (Formal Contract Contemplated) 1. Manifestations of assent that are sufficient to make K will not be prevented from doing so by the fact that parties also intended to prepare and adopt a written memorial; a. Circumstances may show that agreements are just preliminary negotiations. x. When there is a preliminary agreement made (ie letter of intent) and definitive agreement is only contemplated (formal contract), look to see if there was intent to be bound. 1. If no explicit intent, look to other factors: a. Whether type of agreement is usually put in writing (if not, may be binding) b. Whether preliminary agreement contains many details (if yes, may be binding) c. Whether agreement involves a large amount of money (if yes, probably didn’t intend to be bound) d. Whether agreement requires formal writing for full expressions of covenants e. Whether negotiations indicated that a formal written document was contemplated f. Extend of the assurances previously given by the party which now denies a binding contract and the other party’s reliance on the completed transaction 2. Quake Construction v. American Airlines: GC sent P SC letter of intent indicating written contract would be prepared and GC could cancel letter of intent if parties failed to agree on fully executed subcontract agreement. Letter announces that K will be awarded to P and set timeline. Then GC revokes offer saying no K was made. a. Court: Letter was ambiguous so court allowed Parol Evidence to be brought in. Work was to begin very shortly after LoI so court found parties intended to be bound. Also noted letter said K had been awarded to P. xi. Agreement to bargain in good faith (pg. 89) 1. Execution of letter of intent binds party to negotiate in good faith to reach agreement on contract, but parties reserve the right to terminate negotiations should they be unsuccessful in reaching an agreement 2. Must establish a breach of duty to be enforceable 3. Pennzoil v. Texaco (1983) – Getty Oil voted to accept offer from Pennzoil to merge and issued a press release. Getty continued to pursue better offers and later announced agreement with Texaco. Court submitted issue of whether K to jury with instructions that K could be oral and parties could be bound even if not signed – if all essential terms agreed upon and open terms not so critical. Should look to intent. Further, carry with it good faith to bargain at the very least. Was this an agreement to agree or agreement to make a formal contract? a. Every deal carries with it a duty to bargain in good faith. b. Note: Broader approach in this than in Walker v. Keith. UCC (Agreement to Agree – Open Price Term) i. § 2-305 (open price term will not prevent enforcement of K for sale if parties intended to be bound by their agreement) 21 1. 7. The parties if they so intend may conclude a contract for sale even if the price is not settled. In such a case, the price is a reasonable price at the time of delivery if: a. Nothing is said as to price b. Price is left to be agreed by the parties and they fail to agree c. Price is to be fixed in terms of some agreed market or other standard 2. A price to be fixed by the seller or buyer means a price to be fixed in good faith 3. If a price left to be fixed otherwise than by agreement of the parties fails to be fixed through fault of one party the other may at the party’s option treat the contract as cancelled or the party may fix a reasonable price 4. If parties intend not to be bound unless the price is fixed and agreed and it is not fixed or agreed there is no contract SUPPLEMENTING THE AGREEMENT WITH IMPLIED TERMS, OBLIGATIONS OF GOOD FAITH & WARRANTIES a. IMPLIED TERMS (we’re going to imply some types of terms by law regardless of how parties behave) i. Generally 1. Implied terms are not based on conduct of parties; instead, they come from general provisions of law. 2. “Gap Filler” terms and “Off-the-Rack” terms a. Available to everyone in particular types of contracts. b. Parties may have to negate them specifically if they don’t want them in the K. ii. Classical View of Implied Terms: Courts are reluctant to add terms. a. Du Pont v. Claiborne i. Facts: distributor for cleaning products with no set requirement for Claiborne to continue for any period – mutual obligation. ii. Holding: Court agrees and won’t imply terms to a K that don’t exist. iii. Note: This is old common law, but not a universal rule or anything. iii. Modern View of Implied Terms: Courts are likely to intervene and examine intent of parties. a. Implied Best Efforts i. UCC § 2-306 (2): Output Contracts – With exclusive distribution, Imposes implied obligation by the seller to use best efforts to supply the goods and by the buyer to use best efforts to promote their sale (mutual arrangement) ii. Common Law – Most parties must have intended to make contract binding on each. iii. Notes: How do you figure out who is using best efforts? Reasonable interpretation. Also Note: “Best Efforts” standard is probably higher than “Good Faith” standard. b. Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon (Terms implied by law): D fashion designer employed P to have exclusive right to place her indorsements on the designs of others; or to license others to market them in return for one half of all profits and 22 revenues from K’s P makes; D placed her indorsement on clothes without his knowledge and withheld the profits; D says P’s not bound by anything (no consideration) & lacks elements of a K because P did not bind himself explicitly to make reasonable efforts to place the indorsements and market the designs i. Court: This is an implied promise because he had exclusive rights to market and he was to share the profits with her (without him, there would be no marketing or indorsements after the K), so he must have implicitly bound himself to make reasonable efforts makes assumptions as to what the parties would have agreed upon missing term but courts supply the term because they feel the parties intended to have an effective business relationship and theyre reasonably certain what the term should be (supplying omitted term to fit what they must have intended) iv. Reasonable Notification Requirements: 1. Reasonable Notification is required to terminate an on-going oral agreement for the sale of goods in a manufacturer-supplier and dealer-distributor relationship. 2. Leibel v. Raynor Manufact. a. Facts: money. Court looks to UCC § 2-309 and says at least 60-90 days would be reasonable. i. Note: If you’re just a commissioned sales agent, you would be providing personal services in selling the goods, but wouldn’t be subject to Article 2 because you’d be a contractor/employee, but the title of the goods wouldn’t pass to you. 3. UCC § 2-309 a. If no stated time for notice of termination, there is implied notion that K will continue for a reasonable time. b. Court will determine what a reasonable time is, based on the circumstances of the K. c. With a distributor, look to how long it would probably take to sell off the inventory or find a reasonable alternative. d. Reasonable notice under the circumstances could be pretty long. e. Exceptions: Reasonable Notice is not required when: i. K provides for termination on “agreed event,” as long as it’s not unconscionable. ii. No Reasonable Notice is required for a breach of K. v. Requirements Contracts – UCC § 2-306 1. If a buyer says they’ll buy all or none, this is still valid under Corbinian View, because the party is committing itself to two options, one of which has valid consideration. 2. Requirements must be in Good Faith a. Look to pattern of buyer’s needs – can’t suddenly double one month because they expect a price increase. b. Parties can agree on requirements for an estimate. vi. Other UCC Reasonableness-Based “Gap-Filler” Terms 1. UCC § 2-306 (2) – Requires reasonable efforts. b. 23 UCC § 2-305 – Open price terms a. If nothing is said as to price, or left to be agreed upon and parties can’t agree, price will be a reasonable one set by the court. b. If they buyer or seller gets to fix the price, they do so in Good Faith. c. Exception: Where parties intend to be bound only if price is fixed, and it isn’t, then there is no K. 3. UCC 2-309 (1) – If time for shipment is not given, then court can insert a reasonable time. IMPLIED OBLIGATION OF GOOD FAITH only comes into play when there is a contract already i. Generally 1. “Fruits of the Contract” – One party cannot try to intentionally exploit the “fruits of the contract.” 2. “Spirit of the Contract” – One party cannot try to deny the benefits reasonably expected by the other party under the K. 3. Bad Faith Examples: a. Seller concealing a defect in what he is selling b. Builder willfully failing to perform in full, though otherwise substantially performing c. Contractor openly abusing bargaining power to coerce an increase in the contract price d. Hiring a broker and then deliberately preventing him from consummating the deal e. Conscious lack of diligence in mitigating the other party’s damages f. Arbitrarily and capriciously exercising a power to terminate a contract g. Adopting an overreaching interpretation of contact language h. Harassing the other party for repeated assurances of performance 4. Good Faith Examples a. Fully disclosing material facts b. Substantially performing without knowingly deviating from specifications c. Refraining from abuse of bargaining power d. Acting cooperatively e. Acting diligently f. Acting with some reason g. Interpreting contract language fairly h. Acceptance adequate assurances 5. Good Faith applies to agreements, not negotiations. ii. Common Law Approach to Good Faith 1. RS § 205 – Duty of Good Faith and Fair Dealing a. Every K imposes on each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance and enforcement. b. Good Faith obligation usually doesn’t override express terms; however, i. It’s up to the court; Nanakuli v. Shell court found Good Faith more important than express terms. ii. May also override in adhesion contracts. 2. RS § 228 – Satisfaction of Obligor as a Condition a. When the satisfaction of obligor is a condition, and it is practical to determine how a reasonable person, in the position of the obligor, could be satisfied, interpretation is 2. b. 24 preferred under which condition occurs if reasonable person would be satisfied. i. Objective Standard: Applied when commercial quality or operative firmness interpretation is available. ii. Subjective Standard: Applied when there is no readily available standard. 3. Lock v. Warner Bros., Inc. a. Facts: Bros. for first look at her films, with deal for signing them on if they like them. She never gets a deal and sues for breach of good faith. They claim they were only obliged to review. b. Holding: films, but was they’d never buy one, then the K was drafted in bad faith. 4. Morin v. Baystone: GM hired D to build addition on plant. D hired P to supply and erect aluminum walls. K required specific gauge for siding. K provided that all work subject to approval or architect and industry custom would not influence consideration or decision. P did work, GM rejected it and D hired another contractor; D refused to pay balance owed to P. a. Court: Two standards (subjective is honesty; objective is if it is in accordance with reasonable standards of fair dealing); Use objective reasonable person standard to determine satisfaction of K. K spoke of artistic effect of work if within terms of K. Not clear buyer aiming for artistic effect here. Found K was ambiguous relating to artistic effect and acceptability and parties did not reasonably expect to subject P’s rights to aesthetic whims. iii. UCC Approach to Good Faith 1. § 1-304 – Good Faith a. Every contract has obligation of good faith in performance or enforcement in all agreement under the act. b. Good faith permeates the entire UCC. 2. § 1-202 (19) – Definition: Good faith means honesty in fact in the conduct or transaction concerned. a. Agreement that does not bind the buyer to buy only from particular seller is likely viewed as invalid and unenforceable lacking consideration & mutual assent iv. Lender’s Duty – Lenders have a good faith duty to their creditors. v. Employment Contracts 1. “At Will” Doctrine a. First, there is a presumption that employment is “at will,” unless specified term is granted or there is a specified termination clause for cause. b. When time given, may only be fired for just or good cause c. Salary does not imply a one-year employment guarantee. d. Promissory estoppel may bar at will firing 2. Examples of Bad Faith in Employment a. Fired because you wouldn’t do something that violates public policy b. Discrimination on any major grounds c. Additional consideration for more work; might be IP rights, etc. if additional consideration give, defeats at will presumption and requires good cause for firing 25 3. 8. Employee Manuals usually lay out grounds for employment; can be held over “at will” if they explicitly guarantee you won’t be terminated on frivolous grounds, or require cause or whatever. 4. Seidenberg v. Summit Bank: P sold insurance business to D. Explicit covenant in joint marketing and promotion provision; agreement looks to be completely integrated but you can still bring in extra stuff to show what joint marketing programs mean; P received shares of D’s parent company and allowed to be executives of business. K said joint obligation to work together to come up with joint marketing program. D fires P, P sues because didn’t honor marketing program, making promise to hire in bad faith. a. Court: Classic breach of implied covenant of good faith (purpose is allow other side to get reasonable fruits of contract); Allowed parol evidence; additional consideration given for additional marketing program work CAN THE DEFENDANT BAR ENFORCEMENT OF THE AGREEMENT BY SHOWING THAT IT CANNOT BE ENFORCED UNDER THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS? a. Common Law: Classes of Contracts Covered under Statute of Frauds (§ 110) i. If the K falls under the following, cannot be enforced unless there’s a written memorandum 1. A contract of an executor or administrator to answer for a duty of his descendent (executor-administrator provision) 2. A contract to answer for the duty of another (the surety-ship provision) 3. A contract for the sale of an interest in land (the land contract provision) 4. A contract that is not to be performed within one year from the making thereof (the one-year provision) a. Service not capable of being performed within a year from the time of the contract (i.e. more than a year) b. Specific time period for more than one year – SoF applies c. Specific time, more than one year from date of contract – SoF applies d. Nothing said about time – SoF doesn’t apply e. For Life – SoF doesn’t apply ii. Writing must be: 1. Signed by party against whom contract is being enforced 2. Reasonably identifies the subject matter 3. Sufficient to indicate contract made or offered 4. States with reasonable certainty essential terms iii. Multiple writings can be pieced together to form a memorandum (§ 132) 1. Where some writings have been signed, and others have not, a sufficient connection between the papers will allow them to form one memo – connection established by reference to them in same subject matter or transaction 2. Crabtree v. Elizabeth Arden Sales Corp: P negotiated employment contract for sales manager position for D. P accepted D’s offer of two year contract that increased over time. D’s secretary prepared memo on order form. Pay roll change card sent to payroll department. P received first increase but not second. D denied existence of agreement and SoF barred it if it did. a. Court: multiple writings together okay under SoF (one unsigned, one signed); falls under over one year clause iv. Not necessary for signed writing to establish contractual relationship; can be an offer or document that attempts to repudiate contractual obligation (§ 133) v. PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL CAN OVERRULE THE SoF IF: (§ 139) 26 1. b. A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person where injustice can only be avoided by enforcement of the promise 2. The promise did induce the action or forbearance 3. In determining whether injustice can only be avoided by enforcement of promise, the following are significant: a. No other remedies, particularly cancellation and restitution are readily available or adequate b. Definite and substantial character of the action or forbearance c. Extent to which action or forbearance shows evidence of making and terms of promise d. Reasonableness of the action or forbearance e. Extent to which action or forbearance foreseeable by promisor 4. Enforcement of Asserted Oral Contracts within Statute of Frauds under § 139 a. Plaintiff may have to demonstrate that by virtue of his reliance he has suffered injury that will not be compensable on any other basis b. Alaska Democratic Party v. Rice: P worked for D for 4 years when she was fired; P alleges D made oral offer for her to return to her job for two years; P accepted, resigned from her other job and moved to Alaska; P filed suit when she informed she wasn’t going to get it anymore i. Court: Oral agreement can be removed from SoF via Promissory Estoppel by showing existence of promise of employment and reasonably foreseen detrimental reliance c. Munoz v. Kaiser Steel: P left Texas and moved to CA in reliance on D’s promise to employ him as plant foreman for at least three years. P says to make move he sold his house, bought a house in CA. i. Court: can only give PE here for unjust enrichment or unconscionable injury to P; P was paid so no unjust enrichment and on the injury front, he wanted to return to CA anyway and was unemployed before accepting the job to begin with so none here vi. Part performance does not satisfy the SoF, but can potentially recover under restitution theory vii. Freedman v. Chemical: P said D orally promised to pay him commission for procuring a contract for construction with P’s fee payable upon completion; took 9 years but no express duration in K 1. Court: Contracts of no duration or indefinite duration are not within SoF; has to be express in K that cant be completed in a year viii. Hardart Co v. Pillsbury: In series of signed and unsigned writing, signed writing must itself establish contractual relationship between parties; next unsigned writing must on its face refer to the same transaction as the signed one UCC: Classes of Contracts Covered under Statute of Frauds (UCC § 2-201) i. A contract for the sale of goods for price of $500 or more, signed by party against whom enforcement is sought or his authorized agent or broker 1. Contract not enforceable beyond quantity of goods shown in writing 2. Writing not insufficient if it omits or incorrectly states a term agreed upon a. Need not contain all material items and material items need not be stated precisely b. Just need quantity of goods to be sold 27 9. ii. If a merchant sends a confirmation in writing to another merchant, and the merchant receiving the confirmation has reason to know what the writing contains, a statute of frauds defense is not applicable if the receiving merchant didn’t send back a written objection to its contents within 10 days after it was received iii. If the contract does not satisfy the requirements in section 1, but is valid in other respects, it is enforceable if: 1. Specially Manufactured Goods: The goods are specially manufactured for the buyer and not suitable for sale in the ordinary course of seller’s business and the seller has already made a substantial beginning to manufacture the goods 2. Admitting to Sale: if party being sued admits that a contract was made, contract enforceable to quantity of goods admitted iv. Partial performance as substitute for writing can validate K for goods that have been accepted or for which payment has been made or accepted v. Cohn v. Fisher: D enters into oral agreement with P to purchase boat. D gave check to P where D wrote deposit on boat. Parties agreed to meet and D would pay the balance. D didn’t pay rest because he wanted an appraiser and P said no way, D said not buying anymore and P sold the boat to third party at a loss and sued for the difference. 1. Court: Check satisfied SoF requirement for written memo because it had: writing indicating the contract for sale (deposit on boat); signed by the charged party (signature by D); quantity term was expressly stated (deposit on “boat”) vi. GPL v. LP Corp (Merchant Exception): LP enters into oral K to buy cedar shakes from GPL; GPL fills out and signed order forms; LP receives forms that at bottom states needs signature; GPL sends new order forms with different prices and quantities to LP and LP did not object within 10 days. GPL sent first shipment of 13, which LP accepted, but LP did not request remaining 75 loads. 1. Court: Form states “order confirmation” that contained a “sign and return clause” did not make the signing clause a mandatory condition. LP could have objected within 10 days and did not. GPL also relied to its detriment on oral K. c. How to Satisfy Statute of Frauds i. If the SoF applies, then requirements of the SoF must be met/satisfied for the agreement to be enforceable 1. If requirements are satisfied no SoF defense 2. If requirements not satisfied SoF defense applies 3. If SoF defense asserted and established no legally enforceable agreement; no contract liability GROUNDS FOR AVOIDING ENFORCEMENT UCC § 1-103 (b) - Unless displaced by the particular provisions of the UCC, the [common law] principles of capacity, duress, coercion, etc. shall supplement the UCC a. INCAPACITY i. Minority Incapacity – RS § 14 – Infants: Unless a statute provides otherwise, a natural person has the capacity to incur only voidable contractual duties until the beginning of the day before the person’s 18 th birthday. 1. Contracts with minors are voidable – not void – meaning they can be disaffirmed by the minor. Once the minor reaches majority, he has the power to affirm the contract which makes them bound. To disaffirm, the minor must act within a reasonable period of time, or he will be deemed to have affirmed the contract. a. Statutory Exceptions – Some jurisdictions have statutes that allow minors to enter into some specific Ks normally. 28 Minor Disaffirmation – Minors can disaffirm even if parent signed the contract, as long as it doesn’t conflict with public policy. 2. Restoration – A minor need not return lost, consumed, or damaged property unless the legal privilege is nullified. See Restitution below 3. Exceptions to Minor Voidability a. Restitution: i. Some courts hold that a minor’s recovery from an adult may be reduced by the value of the benefit that the minor has received under the contract, or the deprecation in the value of the property purchased. See Dodson v. Shrader ii. Other courts have required minor to make restitution only if he misrepresented his age or willfully destroyed the property. b. “Necessaries” i. A minor is liable for the reasonable value of “necessaries” based on quasi-contractual relief rather than enforcement of the contract. ii. Necessaries are usually defined as food, clothing, and shelter; two interpretations are in practice: iii. Strict Interpretation – No leases even when minors lived away from home and had children of their own. iv. Broad Interpretation – Upholding employment contracts if minor needs to support family c. Tortious Conduct limits disaffirmation; e.g. misrepresenting age, willful destruction. i. Misrepresenting Age – An adult has an obligation to investigate age if they have reason to doubt. ii. Mental Incapacity – RS § 15 – Similar to minority doctrine in necessaries and disaffirmation/ratification; differences are mainly in restitution. 1. Generally: A person incurs only voidable contractual duties by entering into a transaction if either of the following tests is satisfied: a. Tests – at the time of K formation i. Cognitive Test § 15 (a) – Person is unable to understand the nature of transaction or its consequences ii. Volition Test § 15 (b) – Person is unable to act in a reasonable manner in the transaction; and, the other party has reason to know of this condition. Note: this is a more modern approach. 2. Where the K is made on fair terms, and the other party is without knowledge of the incapacity, the power of avoidance terminates the K to the extent that the K has been so performed, in whole or in part, or if the circumstances so changed that avoidance would be unjust. A court may grant relief as justice so requires, although there is a higher standard for restitution. 3. Restitution: Unlike minor incapacity, a mentally incapacitated person must make full restitution to the other party, as long as the K was in good faith and other party had no knowledge of incapacity. 4. Property – If a person’s property is under guardianship due to mental incapacity, they have no capacity to enter into contracts. 5. It is always the burden of the incapacitated party to prove their condition. iii. Intoxication – RS § 16 – A voluntarily or involuntarily intoxicated person, X, may void K if: b. 29 1. 2. 3. the other party, Y, has or had reason to know, that X is/was unable to understand the transaction/consequences of the K, or act in a reasonable manner in relation to transaction. 30