African-American History Month - fchs

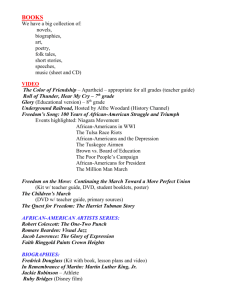

advertisement