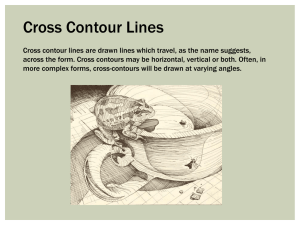

Traditional Contours in Intellectual Property

advertisement