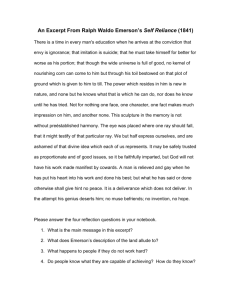

Week 2, day 1 – key terms and creation stories

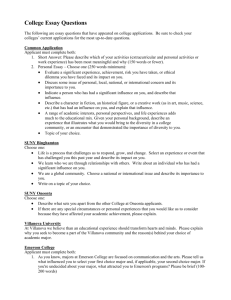

advertisement

Posting on course blog: http://blogs.uoregon.edu/environmentalliterature230/ • Problems accessing blog? • Syllabus – changed blog post #1 due date • What to write about? • How to post?: videos, photos, links, categories, tags, page breaks • Rachel Carson Center Blog • Questions? Literature and Environment Key terms and foundational narratives Checklist of characteristics of environmental texts • The nonhuman environment is present not merely as a framing device but as a presence that begins to suggest that human history is implicated in natural history. • The human interest is not understood to be the only legitimate interest. • Human accountability to the environment is part of the text’s ethical orientation. Checklist of characteristics of environmental texts • Some sense of the environment as a process rather than a constant or a given is at least implicit in the text. Environmental (1995) --Buell, The Imagination How do we read a text for the environment? Stories, metaphors, images … have come to seem deceptively transparent through long usage. If we pay attention we can read in any text and see these stories, metaphors, images at work. Major environmental modes/ motifs • Pastoral • Georgic • Picturesque • Sublime • Wilderness • Ecological tropes ‘The pervasiveness of these phenomena warrant our thinking of them as “master metaphors,” of centuries-long, sometimes millennia-long persistence. We cannot even begin to talk or even think about the nature of nature without resorting to them.’ --Buell, The Environmental Imagination Pastoral • An idealized non-urban space where humans are free from labor and live more closely in tune with the environment and each other. There are often shepherds. Georgic • Also presents an idealized country space, but this one features agriculture rather than shepherding and leisure: there is labor present. Wilderness • Vision of nature as a scary, dark place full of potentially evil forces. Civilization is good; wilderness is bad. In later years, this dichotomy reverses: wilderness is the source of goodness while civilization is the source of evil. Sublime • Landscapes that are both inspiring and terrifying – that give a great sense of aweinspiring magnificence compared with a feeling of insignificance or despair. Wild landscapes that can crush you but are so beautiful you don’t mind! Picturesque • A state between the sublime and beautiful , not controlled by humans but not totally wild. Sometimes seen as the culmination of the older pastoral tradition, it finds aesthetic beauty in nature. • More generally: a way of seeing; seeing the environment as landscape, as scenery; an aestheticization of environment. Ecological tropes • “Web,” “Machine,” “System,” “Chain,” “Scale of Being,” “Ladder,” “Organism,” “Mother,” (term ecology originally from Greek—oikos, meaning “household”) • Cross disciplinary • Sometimes, various modes/motifs can operate at once; for instance, a text could depict a landscape as both both sublime and foreboding, or as both pastoral and wild, depending on the point of view. Anthropocentric/Ecocentric • Not a binary, but a continuum. • Where does a given text (or philosophy) place its value? • Manifestation in language? • Stylistic or formal features of the text. Quiz Genesis • There is historical evidence that Genesis actually contains TWO different creation stories, written in two different time periods and cultures. The “Priestly” (P) version goes from 1:1 to 2:3, and the “Yahwist” (J) version goes from 2:4 to 2:25. The second version is actually much older than the first, dating from the 6th or 7th century B.C. • Important to identify internal rifts, gaps, inconsistencies in texts. • What are some key differences between the two Genesis stories of creation? • What do these accounts imply about the human relationship to the more-than-human world? Genesis vs. Pima • Written text • Oral tradition • Universal/garden • Specific topography, local knowledge of watershed, bioregion • God/man/creatures • Persons/creatures • Centrality of man to narrative • Centrality of other creatures to narrative • “Dominion” • “Make it useful” Historical Overview: Environmental Attitudes • Ancient Greece: pastoral, georgic • 17th century: rise of the pastoral in Europe • 18th century: picturesque; Enlightenment (scientific, ordered, taxonomical views of nature) • 17th/18th centuries in the Americas: Native American attitudes towards the wild as spiritual place and source of resources vying with Puritan fear of wilderness as evil (and also as a source of resources). Historical Attitudes, continued • Late 18th, early 19th century: In Europe, Romantic visions of nature build on picturesque and the sublime – celebration of wild beauty and creation of the noble savage image. In America, pastoral/georgic celebration of agriculture and farming. • 19th C: American wilderness tradition growing – early, the Transcendental movement sees nature and the wild as source of potential truth; Accelerated westward expansion—creation of the “mythic West.” Frontier “closes” in final decade of the century. • 20th C: Policies to protect and preserve wild spaces. Nature as restorative and character forming (“strenuous life” philosophy). Nature as recreation and the celebration of American wilderness as defining national identity. For Thursday Reading: • Review Rowlandson and Crevecoeur • Emerson, “Nature” (note: the pdf isn’t the full essay, though you can find the full essay online: http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl302/texts/emerson/natur e-contents.html Reading questions: • See next slide Assignments: • First blog post due by Wednesday evening, October 3, at 8 pm. For Thursday Reading questions: • At the time Emerson was writing, there really was no such thing as “American literature.” U.S. writers were assumed to be less sophisticated and important. How could Emerson’s essay, Nature, be seen as a manifesto rejecting the European tradition and standing up for American art and philosophy? • In Chapter I, “Nature” (28-30), what is the poet’s unique relationship with the landscape? • In his conclusion Emerson says, “Empirical science is apt to cloud the sight, and by the very knowledge of functions and processes, to bereave the student of the manly contemplation of the whole” (51). What is he saying here? Do you agree with him? What is Emerson’s overall relation to science in this essay? • Emerson was trained as a minister, but then broke with the church and embraced philosophy. How is this essay influenced by a Christian tradition, but how does it also depart from what we would typically consider Christian thought? (look especially at the last few pages)