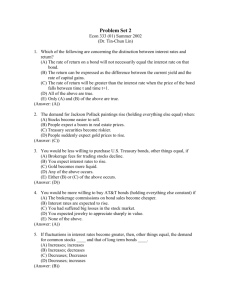

Money and Prices , The Bond Market

advertisement

Money and Prices

Chapter 12

The Bond Market

Chapter 22

Objective

Calculate price indexes and inflation rates.

Calculate a discount bond yields using

discount bond prices.

Calculate Bond Returns using interest rates.

Use the Expectations Theory of the Term

Structure to deconstruct the yield curve.

Calculate the demand for money balances

using nominal GDP and interest rates.

Money

Money is a tool for conducting transactions and, like

all tools, is subject to technological advance.

Barter was replaced by commodity money, precious

metal with intrinsic value.

Problems (Issues) with commodity money

–

–

–

Commodities used as money can’t be used for other

purposes.

Supply of money determined by availability of resources.

Government must share the revenues from the creation of

money (Perhaps only a problem from governments point of

view).

Fiat Money

Fiat money is intrinsically valueless commodity (typically paper)

widely accepted as payment rendered (by government

command.

First paper money circulated in Szechwan province during the

Northern Sung dynasty. Szechwan had iron coins which are

heavy and rusty. Banks issued receipts for the coins called

chiao-tzu which circulated as the origins of paper money.

In 1161, under the Southern Sung dynasty, the government

developed a paper called hui-tzu which eventually developed

into first nationwide paper money.

Decade-by-Decade History of Hui-tzu

Observations

For many years, inflation

lags money growth rate.

Money growth rate

accelerates near turn of the

century.

During final years of

dynasty, inflation is faster

than money growth.

Why?

(Cite: F. Lui, JPE 1983)

Years

Money Growth

Inflation

1165-75

7.13%

1175-85

0.94%

1185-95

13.06%

1195-1205

5.47%

1205-15

4.96%

1215-25

1.60%

1225-1240

3.91%

-1.43%

2.13%

5.39%

4.20%

0.01%

1.80%

16.58%

What is Inflation?

Define Inflation as the

growth rate of prices.

The Greek letter π is

often used as a symbol

of inflation

Pt

1 t

Pt 1

Pt Pt 1

1

Pt 1

Aggregate Prices

We also might want a

measure of average

prices.

Aggregate price measures

are weighted averages of

the prices of a set of

goods n = 1..N relative to

their price in a base year

B.

Two main types of

measures

1.

2.

Price Indices

Price Deflators

w1

pt ,1

pB ,1

w2

pt , 2

pB , 2

.... wN

w1 w2 .... wN 1

pt , N

pB , N

Price Indices

Most commonly used price index is the Consumer

Price Index (CPI)

In constructing the CPI, statisticians calculate the

total expenditure of the average household during a

benchmark year.

The weight on good n in the CPI is the share of

expenditure in the base year that was on good n.

Price Deflator

Another type of price aggregate

is the deflator which is

calculated simultaneously with

a real quantity aggregate.

The deflator uses weights

which change over time.

The weight for good n in the

GDP deflator is the ratio of the

quantity of that good relative to

real GDP.

The GDP deflator is also the

ratio of nominal GDP to real

GDP. Deflators can be

constructed for any subcategory of GDP.

p t,1 p B,1q t,1

p B,1

Qt

p t,2 p B,2 q t,2

p B,2

p t,N p B, N q t,N

p B, N

Pt

PQt

Qt

Qt

Qt

....

HK Price Aggregates

(Base Year 2000)

120

110

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

86

88

90

92

CPI

94

96

98

GDP Deflator

00

02

Adjusting for Inflation/Converting Current

Price Series into Constant Price Series

One may have a time series of a nominal

aggregate, Nt, (in current prices) without

the microeconomic data necessary to

construct a corresponding real aggregate.

We can use some price index to “adjust for

inflation” effectively converting into a real

variable.

1.

2.

Select a reference or base year.

Series measured in base year dollars is

PB

N Nt

Pt

B

t

Role of Money

1.

2.

3.

Money has 3 roles

Medium of Exchange – Money is a

technology for engaging in transactions.

Unit of Account – Value of most goods and

assets is measured in money.

Store of Value – Money is an asset. It can

be exchanged for goods in the future.

Monetary Aggregates

Real world Different

assets have different

levels of usefulness in

transactions.

Money is measured in

sums of these assets.

M2 & M3 include less

liquid assets and are

called broad money.

M1 is the most liquid

type of money.

Assets

M1

Currency in

Circulation+

Checking Deposits

M2

M1 + Other Deposits

(Savings, Time, CD’s)

at Fully Licensed

Banks

M3

M2 + Deposits at

Finance Companies

Monetary Aggregates in HK

(Nov. 2002)

Million HK$

M3

M2

Million HK$

M1

0

500000 1000000 1500000 2000000 2500000 3000000 3500000 4000000

Velocity/Liquidity

Define the ratio of transactions to the supply of

money as ‘Velocity’, the speed with which money

circulates.

The value of transactions is nominal GDP.

PY

V

V M P Y

M

The inverse of velocity is the willingness to hold

money between transactions or the willingness to

hold a liquid position, L

1 M

L

V PY

Rules of Thumb

If Z = X×Y, then gZ = growth rate of z

gZ ≈ g X + g Y

Example: Z = Nominal GDP = P×Y

gZ ≈ g P + g Y = π + g Y

Growth rate of Nominal GDP is approximately

equal to inflation plus growth rate of real GDP.

If Z = Y/X, then

g Z ≈ gY - g X

Example: Z = Per Capita Real GDP = Y/POP

gZ ≈ gY - gPOP

Growth rate of per capita real GDP is growth rate

of real GDP minus the growth rate of population.

Quantity Theory & Inflation

Using the definition of velocity, we can say

gY + π ≈ gM + gV = gM - gL

This gives us an equation for inflation.

–

–

π ≈ (gM - gY ) + gV

π ≈ (gM - gY ) - gL

Inflation (the growth rate of prices {money per good})

is equal to the growth rate of money minus growth

rate of goods unless there are significant changes in

the willingness to hold money.

Sung Dynasty

In the early years of the introduction of huitzu, there was likely an increasing willingness

to hold new form of money,

gL > 0 → π < (gM - gY )

In the final years of the Sung Dynasty, there

was a reduced willingness to hold Sung

money,

gL > 0 → π > (gM - gY )

Ordinary Determinants of Velocity

What determines the willingness of people to hold

money or conversely what determines the speed

with which they spend money.

Money is an asset that does not pay interest. When

you hold money, opportunity cost is lost interest. The

higher is the interest rate, the greater is the

opportunity cost.

Some forms of money, (e.g. savings and time

deposits) pay interest, however, they are lower than

the interest rate on bonds.

Nominal Interest Rate

The nominal interest

rate is the ratio of

money you get in the

future relative to the

money you give up

today, i.e. the time

value of money.

If you give the bank $1,

they will give you $1+i

after one period.

i ≡ Net Nominal Interest

Rate

Liquidity demand is a

negative function of the

nominal interest rate.

L(i-)

Money Demand Curve

Write the Quantity Equation as a money

demand curve

MD = L(i)∙PY

Given the level of nominal GDP, the nominal

interest rate will determine the demand for

money.

We write this as a downward sloping

relationship between MD and i.

i

MD

M

Money Demand

Q: Why does the money

demand curve slope

down?

A: The greater is the

nominal interest rate,

the greater is the

opportunity cost of

holding money.

Q: What shifts the money

demand curve?

A: An increase in the nominal

GDP will increase the need

for money for transactions.

This will shift the demand

curve out. A reduction in

nominal GDP will shift the

demand curve in.

Money Supply

Central banks in large economies (the US, Euroland)

typically set an interest rate target though they

directly control the money supply.

Relationship between interest rates and money

demand give them tools to control interest rate.

Set money supply as straight line indicating central

bank control.

Given nominal GDP, interest rate will set money

supply equal to money demand.

MS

i

iEQ

MD

M

Reaching Equilibrium

If i > iEQ, then money demand will be less

than money supply. People will buy bonds

which will reduce the interest rates that

borrowers must offer.

If i<iEQ, then money demand will be greater

than money supply. People will sell bonds to

get money. This will increase the interest rate

that bond issuers must sell.

Open Market Operations

The government authority controlling the money supply is the

central bank. In Hong Kong, this is Hong Kong Monetary

Authority (HKMA)

Central banks typically (though not in HK) change the money

supply through open market operation (OMO). An OMO is the

purchase or sale of government bonds by the central bank.

In an open market purchase, the central bank prints new money

and uses it to buy bonds. This increases the supply of money in

the short run.

In an open market sale, the central bank sells some of its stock

of bonds and receives existing money in exchange. This

reduces the supply of money in the short run.

Interest Targets

When the central bank selects an interest rate target,

they will instruct their bond department to conduct

OMO’s to keep interest rate in some market (typically

interbank lending market) inside some target zone.

If money demand increases, the bond dept. will do

an open market purchase.

If money demand falls, the dept. will do an open

market sale.

MS

1.

i

Increase in money demand

due to increase in GDP

iEQ

MD’

2. Open Market Purchase

increases money supply

MD

M

Liquidity Effect

In the very short run (less than 3 months or so), open market

operations can be thought of as having little effect on nominal

GDP.

An unexpected increase in the money supply growth will

increase the available liquidity. This will lead to increased

demand for bonds and reduced interest rates.

An unexpected decrease in the money supply will reduce

available liquidity, causing sales of bonds and upward pressure

on interest rates.

The negative short-run relationship between money supply and

interest rate is called the liquidity effect.

MS

i

MS’

1. Open Market Purchase

increases money supply

iEQ

Excess Liquidity causes

interest rates to fall

iEQ’

MD

M

Long-run Neutrality of Money

Hypothesis: In the long run, real production

and relative prices of different goods do not

depend on the level or growth rate of money.

Reason: Money is of intrinsically no value.

Money prices are just an arbitrarily chosen

value. In short run, money may matter due to

market imperfections, but cannot matter in

long run.

Real Interest Rate

The price level of goods is Pt

and the interest rate is it.

If you buy $1 worth of bonds

you will give up opportunity to

by 1/Pt goods.

You will get $1+i in the future

which will allow you to buy

1+i/Pt+1 goods in the future.

The payoff of future goods

relative to foregone current

goods is the goods interest rate

or the real interest rate.

1 it

Pt 1

1 i

1 rt

1

Pt 1

Pt

Pt

1 it

1 t 1

rt it t 1

Ex Ante vs. Ex Post Real Interest Rates

The future inflation rate, πt+1, is not known at

the time a bond is purchased.

Ex Ante Real Interest Rate is the interest rate

less the expected inflation rate, πEt+1.

rAt = it - πEt+1

Ex Post Real Interest Rate is the interest rate

less the actual realized inflation rate

rPt = it - πt+1

HK Interest Rates

1 Year HK Government Bond Rates

20

15

10

5

0

-5

-10

1992

1994

1996

Nominal Rate

1998

2000

Ex Post Real Rate

2002

Fisher Effect

In the long run, the money growth rate does

not affect the real interest rate.

Money growth affects the interest rate

through its affect on inflation.

The higher is future inflation, the higher is the

interest rate.

Long Run Inflation and Interest Rate

Assume there is a long run money growth rate, gM , and long run

output growth rate, gY. Also assume there is a stable real interest

rate, r.

If there is a stable long run inflation rate, then there is a stable

nominal interest rate.

If there is a stable nominal interest rate, then velocity is stable, gV =

0.

If velocity is stable, then π = gM – gY

If there is a stable inflation rate, then nominal interest rate is i=r+ gM

– gY.

An increase in the money growth rate will increase inflation in the

long run. Given a target real interest rate, this will increase the

nominal interest rate demanded by lenders.

Money and Interest Rates

In short run, there is a negative relationship between

interest rates and an increase in money growth.

In the long run, there is a positive relationship

between an increase in money growth and the long

run interest rate.

This dichotomy is often manifested in the yield curve,

the difference between a long-term interest rate and

a short-term interest rate.

Deflation

Deflation is defined simply as negative

inflation or falling prices over time.

Nominal Interest Rate has a lower bound.

Since money pays 0% rate, bonds that pay

less than 0% cannot be sold. Thus, the lower

bound of the nominal interest rate is 0%

When interest rate reaches lower bound (as

in HK now) deflation pushes up real interest

rate.

Long-term Interest Rates

Bonds are sold with different maturities. For

example, there are Hong Kong government

bonds with maturities as long as 10 years.

An expansion in money growth will have

different effects on interest rates on longterm bonds and short-term bonds

Consider two strategies which should

have the same expected pay-off.

Starting with $1.

Buy a two year discount bond and hold it

for two years. Payoff:

(1 i2 ) 2 (1 2 i2 i22 ) 1 2 i2

2. Buy a 1 year bond. After 1 year, invest

pay-off in another 1 year bond. Payoff:

(1 i1 ) (1 i1e, 1 ) 1 i1 i1e, 1 (i1 i1e, 1 ) 1 i1 i1e, 1

1.

Equal pay-offs imply that yield on a

two year bond is equal to the expected

average yield of 1 year ebonds over the

next two years. i i1 i1, 1

2

2

In general, if the pay-off for investing in

an n period bond should be the same as

the pay-off from rolling over 1 year

bonds for n periods:

(1 in ) n (1 i1 ) (1 i1e, 1 ) (1 i1e, 2 ) ... (1 i1e, n1 )

Then a n period bond yield is

(approximately) equal to the average

expected yield on 1 period bonds

between today and date n.

e

e

e

in

i1 i1, 1 i1, 2 ... i1, n 1

n

On average, longer term bonds have higher interest

rates than short-term bonds.

Mean Yield Curve

Maturity

8

7.5

7

6.5

6

Series1

1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 5 Year

Yield

10

Year

Discount Bonds

There are many types of bonds. The simplest type of

bond is a discount bond. The issuer of a discount

bond makes a single payment (called the face value)

at some designated time T periods from now.

The standard unit of bonds are in $100 of face value.

So if a bond price is quoted at PB, this is the price

per $100 worth of face value.

Ex. If a bond had a face value of $10,000 and you

were quoted a price of 90, you would have to pay

$9000 for this bond.

What is a Bond

Bonds are a promise to repay certain amounts of

money at specific dates in future.

Most bonds specify specific amounts of currency

units that will be repaid (unlike stocks which entitle

owner to a share of profits).

Bonds unlike bank loans can be traded on securities

markets.

Since governments cannot issue equity, they rely on

bonds for financing. Government bonds are a large

share of world bond market.

HK Dollar Bond Market

Listed HK$ Bonds

Total: HK$ Million 607962

State-owned

12%

Supranational

7%

Bank

7%

Corporate

23%

State

51%

Bond Prices and Interest Rates

The interest rate quoted on a discount bond of

maturity date T is calculated as P (1 100

i )

If you put PB into a bank account that offered and

interest rate of it,T for T years, you would have a final

balance of 100.

This interest rate is the average return you will get

on your bond if you hold it for T periods which is

referred to as the yield to maturity or the yield.

Holding interest rates constant, the price of a

discount bond gets closer to 100 as the bond

matures.

B

t ,T

T

t ,T

Implications

There is an inverse relationship between the

price of a bond and the interest yield on the

bond.

When a bond is relatively cheap, an investor

can earn a high return by buying it and

holding it until maturity.

When interest rates rise, bond prices fall.

Implications

Long-term bond prices are

more sensitive to a

persistent increase in

interest rates because they

are held for many periods.

The percentage change in

discount bond prices are

approximately equal to the

negative maturity level.

P

T i

P

B

T

B

Example: Interest rates at all

maturities change from 2%

to 3%: Δi=.01

–

–

–

The % change in a two year

bond price will be

approximately -2%.

The % change in a 3 year

bond price will be

approximately -3%

The % change in a 10 year

bond price will be

approximately -10%.

Ex Ante Yields vs. Ex Post Returns

Yields are the average returns that a bond

holder can expect to earn in the future.

Ex post returns are the returns that someone

has earned by holding bonds over a past

period.

For discount bonds, the annual ex post bond

return, Rt, will be the change in the price level

over the period

Pt B Pt B1

Rt

Pt 1

B

Inflation: Enemy of Bondholders

A surprise increase in money growth may

reduce short-term interest rates through the

liquidity effect, but it can be expected to

increase long-term interest rates through the

Fisher effect.

Therefore, an increase in money growth is

likely to increase long-term bond yields.

This will reduce long-term bond prices and

lead to negative nominal returns to bonds.

Costs of Expected Inflation

Shoe Leather Costs – Money is a technology

for engaging in transactions. The greater is

inflation, the greater the cost for individuals

of holding money. Individuals must make

efforts as a substitute for the convenience of

holding money.

Menu Costs – Firms must engage in costs of

changing posted prices.

Costs of Unexpected Inflation

When actual inflation is greater than

expected inflation, ex post real interest rates

are less than actual interest rates.

Inflation is a double whammy for long-term

bond holders. A rise in inflation increases

interest rates reducing returns, then reduces

the real value of those returns.

Bond Investment

An Indian investor decided to invest Rp.1,000,000 in

Indian bonds in 1970. The strategy will be to buy

bonds in 1970 and roll over all payments of principal

and interest back into a bond fund.

The average return on Indian bonds during this

period was 6%

In 1990, the Indian investor would have Rp.

3,253,992.04 in savings, tripling his money in twenty

years.

Real Returns

However, the average Indian inflation rate

during this period was 8.3%.

Thus, in 1990, the pay-off of the savers bond

investment would only buy the same amount

of goods as Rp.$622,394 would have bought

in 1970.

Investing in Indian bonds has cut the

purchasing power of savings nearly in half!

Inflation Risk

Unexpected inflation is bad for long-term

bond holders.

Volatile inflation is a source of risk for bond

buyers.

Extra risk pushes up interest rates, pushes

down bond prices.

Inflation risk premium can lead to higher

interest rates.

Floating Rate Bonds

Bond holders who are sensitive to inflation

risk often purchase floating rate bonds.

If some benchmark interest rate rises, the

holders of floating rate bonds receive an

extra payment.

Most mortgages are floating rate loans.

Government debt is typically fixed rate.

HK$ Bond Market: Fixed vs.

Floating

Floating Rate Bonds as a % of HK Dollar Bond Market (excl. Ex.

Fund)

% of Issues w/ Floating Rates

45.00%

40.00%

35.00%

30.00%

25.00%

20.00%

15.00%

10.00%

5.00%

0.00%

< 3Years

3 to 5 Years

Maturity Date

> 5 Years

Seignorage

If inflation is so bad, why is it so common?

When governments print money, they can use it to

finance government spending.

Seignorage – Revenue raised by a central bank

through printing money due to the difference

between the face value of money and the cost of

production.

For paper money, cost of production is very small.

Seignorage & Real Seignorage

When the government prints

new money, they can buy

more goods = Mt – Mt-1.

The real value of

government money printing

is proportional to real GDP.

Factor of proportion is

function of the money

growth rate and demand for

liquidity.

M t M t 1

Pt

M t M t 1 M t 1 M t

M t 1

M t Pt

gM

LY

M

1 g

Inflation Tax

Who pays for seignorage? The ordinary

household whose value loses real money

overtime.

Obtaining revenues through seignorage has

diminishing returns.

–

The higher is the money growth rate, the faster is

inflation. The higher is inflation, the higher is the

nominal interest rate. The higher is the nominal

interest rate the less money holding there will be.

Relative Price Changes

Overall, inflation measures often mask

changes in relative prices.

Housing prices in HK have been more

volatile than other types of prices.

When inflation is high, rent inflation is higher

than average.

When inflation is low, rent inflation is lower

than average

HK Inflation: 1991-1997

HK Inflation: 1998-2001

12.00%

0.00%

Appliances

-1.00%

10.00%

-2.00%

8.00%

-3.00%

6.00%

-4.00%

-5.00%

4.00%

-6.00%

2.00%

-7.00%

0.00%

Appliances

Rent

-8.00%

Rent