the Slides

advertisement

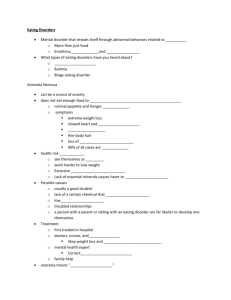

Family Therapy and Mental Health University of Guelph Office of Open Learning 1 Reflections on the Course So Far Comments Questions Assignments 2 Today This is the End! Family Therapy and Eating Disorders Life in the CRPO Jeopardy Evaluations 3 Family Therapy & Eating Disorders Assessment and Treatment Spectrum of Weight-related Disorders Bulimia Nervosa Anorexia Nervosa Unhealthy Dieting Disordered Eating Binge Eating Disorder Obesity DSM 5 Criteria: AN A. B. C. Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. Significantly low weight is defined as a weight that is less than minimally normal or, for children and adolescents, less than that minimally expected. Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight. Disturbance in the way in which one’s body, weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body, weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of current low body weight. DSM 5 Criteria: AN Restricting type: during the last 3 months, the individual has not engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behaviour. This subtype describes presentation in which weight loss is accomplished primarily through dieting, fasting, and/or excessive exercise Binge-eating/purging type: during the last 3 months, the individual has engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behaviour DSM 5 Criteria: BN Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: A. Eating, in a discrete period of time (any 2 hr. period) an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (can’t stop or control what or how much one is eating) DSM 5 Criteria: BN 2. 3. 4. 5. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviours in order to prevent weight gain (e.g. vomiting; use of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or other meds; fasting or excessive exercise) The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviours both occur, on average, at least 1x/wk for three months Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of AN DSM 5 Criteria: BED Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: A. Eating, in a discrete period of time (any 2 hr. period) an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (can’t stop or control what or how much) DSM 5 Criteria: BED The binge-eating episodes are associated with three (or more) of the following: B. Eating much more rapidly than normal Eating until feeling uncomfortably full Eating large amounts of food when not hungry Eating alone because of embarrassment Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterward DSM 5 Criteria: BED C. D. E. Marked distress regarding binge eating is present The binge eating occurs, on average, at least 1x/wk for 3 months The binge eating is not associated with the regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviours and does not occur exclusively during the course of AN or BN Eating Disorders: Prevalence Total # of cases in the population Indicates the demand for care Anorexia Bulimia 0.3% for young females 1% in women; 0.1% in men Binge Eating 1% in general population (van Hoeken, Seidell & Hoek, 2005) Eating Disorders: Incidence # of new cases in pop. in a specified period of time (usually one year) Represents the moment of detection vs. onset Anorexia 8 per 100,000 Bulimia 12 per 100,000 (van Hoeken, Seidell & Hoek, 2005) Eating Disorders & Mortality mortality rate associated with AN is 12 times higher than the death rate of ALL causes of death for females 15 – 24 years old 20% of people suffering from anorexia will prematurely die from complications related to their eating disorder, including suicide and heart problems Anorexia Associated Disorders National Association of Nervosa and Etiology or Etiology Eating disorders are multi-determined “Unlike some illnesses, recognizing the cause(s) does not necessarily suggest a solution” (Lask & Bryant-Waugh, p. 51) e.g. CBT approach (Fairburn) Predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors Individual, family, and sociocultural factors Assessment Screening The SCOFF Questionnaire 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Do you ever make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full? Do you ever worry you have lost Control over how much you eat? Have you recently lost more than One stone (6.35 kg) in a three month period? Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin? Would you say that Food dominates your life? A score of more than 2 positive answers indicates a need for a more detailed assessment (John Morgan, BMJ, 1999) Assessment Symptoms of AN weight loss amenorrhea depression irritability sleep disturbance fatigue weakness headache dizziness faintness constipation non-focal abdominal pain feeling of “fullness” polyuria intolerance of cold Mehler & Andersen, 1999 Assessment Signs of AN emaciation hyperactivity cardiac arrhythmia congestive heart failure bradycardia hypotension dry skin brittle hair brittle nails hair loss on scalp “yellow skin”, especially palms lanugo hair cyanotic and cold hands and feet edema (ankle, periobital) Mehler & Andersen, 1999 Assessment Symptoms of BN weight fluctuation irregular menses esophageal burning/heartburn nonfocal abdominal pain abdominal bloating/gas lethargy fatigue headache constipation/diarrhea/ hemorrhoids swelling of hands/feet frequent sore throats depression swollen cheeks, parotid/ submandibular gland enlargement Mehler & Andersen, 1999 Assessment Signs of BN calluses on the back of the hand salivary gland hypertrophy erosion of dental enamel periodontal disease tooth decay brittle nails petechiae perioral irritation mouth ulcers blood in vomit edema (ankle, periorbital) Mehler & Andersen, 1999 Assessment Multi-disciplinary Individual Family Interview, self-administered questionnaires Genogram, ecomap, family history Boundaries, communication, conflict, emotional expression, etc. Nutritional Medical Medical history, physical examination, lab tests Assessment Individual Interview Get the “story” of the client’s problem(s) “What brought you here today?” Obtain a complete history of ED Track when and how concerns arose and how they translated into specific behaviours How it started, when it was at its worst, what it’s like now Detailed nutritional history Describe a typical day of eating Vegitarianism/veganism, nutritional supplements Perceptions about family’s view on food, weight loss, and health Assessment Individual Interview Weight and shape concerns Other changes: isolation, mood, school, social Other mental health issues/diagnoses Self-harm and suicidality Family stressors/changes For adolescents: Smoking, drinking, abuse of street drugs or medications Sexual history Abuse history Assessment Comorbidities 50-75% 25% 30%-37% 12%-18% depression/dysthymia O.C.D. (lifetime prevalence) substance abuse in B.N. substance abuse in A.N. (binge-purge type) 42%-75% personality disorders 20-50% sexual abuse Assessment Body Mass Index Assessment Body Image Measure of Body Image Distortion - Select the body that best represents the way you think you look - Interviewer estimates actual size - Degree of distortion = actual – perceived (Figure Rating Scale, Skunkard & Sorenson, 1987) Assessment Questionnaires Most popular: Eating Disorder Inventory 3 (Garner, 2004) 91 item self-report Drive for thinness, bulimia, body dissatisfaction Eating Disorder Examination 16.0 (Fairburn, Cooper & O’Connor, 2008) Structured clinical interview, used most in research EDE-Q 6.0 – 28 item self-report; validated with EDE Eating Attitudes Test (Garfinkel & Garner, 1979) 26 item self-report of symptoms Assessment Features of Medical Concern Marked food or fluid restriction Frequent self-induced vomiting (>2x/day) Frequent laxative or diuretic misuse (>2x/day) Heavy exercising when underweight Rapid weight loss (>1kg/week for several weeks) BMI of 17.5 or below Episodes of feeling faint or collapsing Episodes of disorientation, confusion or memory loss Chest pain, shortness of breath Swelling of ankles, arms or face Blood-stained vomit Assessment Family Sessions Meet with both parents and client, if possible Discuss confidentiality Complete genogram At least three generations (child, parents & grandparents) Try to engage each member, allow client to listen while mom and dad are interviewed (re. family secrets) Ask about: addictions, abuse, moves, work, school, bullying, separation/divorce, miscarriages, any hx. of mental health issues, closeness/distance, conflict, cutoff, how emotions are handled (re. validation) Assessment Family Sessions Ask client (if appropriate) to tell the story of ED: When did it first start? What happened? What did you notice? What else was going on at the time? Often goes on for a while before anyone knows How did it progress? Normalize secrets and shame When did others first notice? Who noticed? What was said/done? How did you react? When was the term ‘eating disorder’ first used? By who? What happened? Get history of treatment and response, what worked or didn’t Family involvement, reactions, response (e.g. anger, fear/worry, hopelessness) Levels of Intervention LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 Non-intensive outpatient treatment (community, group based) Psycho-education, motivation, body image, self-esteem May include individual and/or family therapy Medical management component (GP, psychiatrist, dietician) Specialized intensive day treatment CBT, DBT, EFT, etc. Usually for clients not responsive to Level 1 approach LEVEL 3 Inpatient care for more severe cases of eating disorders May include medical hospital admission for weight restoration e.g. nasogastric tube Medical stabilization then combination of individual, family, and group therapy The Stages of Change & Motivation The Stages of Change 3. Preparation “I know I have an eating disorder and I am getting ready to change” 2. Contemplation “I think I have an eating disorder but I’m not sure if I’m ready to change” 4. Action “I have an eating disorder and I am actively working on changing it” 1. Precontemplation “I don’t have an eating disorder” 5. Maintenance “I am in recovery from an eating disorder and I am actively working to maintain it” Relapse “I have been in recovery and slipped back into old behaviors/patterns” The Stages of Change: Precontemplation clients present as HARD (hopeless, argumentative, resistant, debate) use MI principles: respect, empathy, nonjudgment focus on engagement, therapeutic alliance use of humour give them information, don’t argue, counter myths, raise some doubt, ask them to describe a typical day for them, monitor/observe the problem, screening tools share information, be objective The Stages of Change: Contemplation ambivalence about change write friend/foe letters use decisional balance (cost/benefit analysis) not pushing, but allow them to make decision help decrease the cost of changing help clarify their vision of themselves and their life (ACT) encourage small steps to behaviour change with high probability of success, frame as an “experiment” look for and encourage any shifts (complimenting) functional analysis - what function does the behaviour serve? (behaviour chain, ABC exercise) The Stages of Change: Preparation feel consequences of behaviour more internal emotional shift starts increased commitment to self to change has made some small changes think about what you stand to lose and how you will cope (5 yr. letter, goodbye letter) social skills training, problem solving, assertiveness validate small changes, goal setting contracting for changes, monitor follow through The Stages of Change: Action have successfully altered behaviour clients in action SOAR (substitute alternatives, open up to others, avoid and counter high risk situations, reward themselves) client may feel over-confident – discuss slips vs. relapse relapse prevention strategies, coping w/triggers response rehearsal – “Practice, practice, practice!” substitute alternatives for problem behaviour encourage honesty in talking about problems and progress encourage self-reward for positive changes made help them take responsibility (to own) changes made reinforce stories of change and increase hope Motivational interviewing is a “client-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence” (Miller & Rollnick, 2002, p. 25) Three essential questions: Are they willing to change? Are they able to change? Has to do with the importance of change When they connect changing with something they value, something important to them Difference between where you are and where you want to be Identify and amplify values that are contrary to present behaviour May feel willing but not able, high importance but low confidence (e.g. past failures) – provide hope, encouragement, share success stories, testimonials If they believe it’ll work and that they can do it, they usually do Are they ready to change? “I want to, but not now” – relative priorities One can be willing and able to change, but not ready to do so Motivational Interviewing 1) Expressing accurate empathy “accurate empathy involves skilful reflective listening that clarifies and amplifies the person’s own experiencing and meaning, without imposing the counsellor's own material” (Miller & Rollnick, p. 7) understand client without judging, criticizing or blaming acceptance of people as they are seems to free them to change helps to reveal ambivalence about change Motivational Interviewing 2) Develop discrepancies MI is intentionally directed towards the resolution of ambivalence in the service of change create and amplify a discrepancy between present behaviour and broader goals and values (“cognitive dissonance” - Leon Festinger, 1957) seek to enhance this within the person (internal motivation) “people are more often persuaded by what they hear themselves say than by what other people tell them” (Miller & Rollnick, p. 39) rehearse eating disordered thinking when defensive discrepancy has to do with the importance of change Motivational Interviewing 3) Avoid argumentation “the more a person argues against change during a session, the less likely it is that change will occur” (p. 8) the least desirable situation is for the counsellor to advocate for change while the client argues against it avoid labelling which encourages a defensive reaction monitor resistance for feedback about your approach (e.g. is the client getting angry or defensive?); it may be a signal to shift your approach or respond differently Motivational Interviewing 4) Roll with the resistance recognize and accept that a low level of importance of change is a normal stage in the process reluctance to change problematic behaviour is to be expected convey understanding and acceptance of resistance turn the question or problem back to the client, actively involving them in problem solving counsel in a reflective, supportive manner, and resistance goes down while ‘change talk’ increases Motivational Interviewing 5) Support self-efficacy belief in oneself and hope for the future hope and faith are important elements of change (re. common factors – 15%) enhance client’s confidence in his or her capacity to cope with obstacles and to succeed in change (e.g. exceptions) recognize and acknowledge past success (complimenting) assign tasks geared toward their level, with high probability of success give choices and options and let the client choose how to proceed empower client by encouraging her/him to take responsibility for any changes made, helping them own their success Methods of Treatment Family-Based Therapy Family-Based Therapy Began with Salvador Minuchin and his team at the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic Structural family therapy – applied family systems principles to treatment; the family as the unit of treatment vs. the individual Identify and change transactions that maintained the illness (second-order vs. first-order change) Introduced the family meal as part of therapy in 1975 Reported effectiveness of 86% in 53 cases followed up over almost eight years Results and treatment described in: Psychosomatic Families: AN in Context (1978) Family-Based Therapy Research on family therapy with eating disorders continued at the Maudsley Hospital in London through the 80’s and 90’s Result was the Treatment Manual for AN (Lock, Le Grange, Agras & Dare, 2001) Became known as the “Maudsley model” Believed parents should be seen as the most useful resource in the treatment of adolescents with AN Described as a “new form of family therapy” developed primarily by Christopher Dare Main contributions were: exonerating parents of blame, raising parent’s anxiety to fully engage them in treatment, focusing on weight restoration before any other issues are addressed Family-Based Therapy Principles 1. 2. 3. 4. Agnostic – no blame, don’t look for cause Pragmatic – initial focus on symptoms, other issues can wait until less symptomatic Empowerment – parents are responsible for weight restoration, family as a resource Externalization – not pathologizing, separate child from illness, respect Family-Based Therapy Phase I (Sessions 1-10) Phase II (Sessions 11-16) Transfer control back to adolescent Phase III (sessions 17-20) Parents restore child’s weight Focus on other issues Termination Family-Based Therapy Phase I Joining, family history, ED history, assess family functioning (e.g. problem solving, communication, roles, emotional expression, conflict resolution, boundaries, etc.) Reduce parental blame, separate illness from client Heighten concern and seriousness of illness Charge parents with task of weight restoration Family meal: “Bring in a meal that would set your child on the path to recovery” Coach parents: “One more bite” Assess family process during eating Family-Based Therapy Phase I Keep it focused on ED Help parents take charge of eating Mobilize siblings to support client Phase II transition: When weight is at minimum 90% IBW Client eats without significant struggle Parents demonstrate empowerment over the eating disorder Family-Based Therapy Phase II Support parental management until client can gain weight independently Transfer control to adolescent Explore adolescent developmental issues relative to ED (friends, dating, sexual orientation, dependenceindependence, decisions about school/career) Highlight differences between adolescent’s own needs and those of ED Close sessions with positive feedback Family-Based Therapy Phase III transition: Phase III Symptoms have dissipated but body image concerns may remain Revise parent-child relationship in accordance with remission Review and problem-solve re. adolescent development Review progress and terminate treatment Family-Based Therapy Strengths of model: Thought of as more holsitic treatment Attempts to redress boundary issues, putting parents “back in control”; empowering for parents Separates the person from the problem – less shame Weaknesses of model: Disrespectful of client’s suffering from AN Seems manipulative at times (e.g. playing on parent’s fear) Critique of ‘evidence’ on which approach is based – may only be effective for those <19 with a <3 yrs. in ED (Fairburn, 2005) Multi-family Groups Between three and eight families with several therapists for a number of sessions (8 – 12) Grew out of FBT work; discuss issues and share a meal Collective sharing of experience and expertise Discuss both eating-related problems and non-eating disorder themes A resource-focused, non-pathologizing approach to family involvement Uses the ‘expertise’ of those who have struggled with the illness – experienced families help new families Research on effectiveness is currently underway Methods of Treatment Collaborative Care Collaborative Care Cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; 2013) 1. Thinking style • 2. Interpersonal relationships • 3. Expressed emotion; accommodating and enabling Pro Anorexia (impact of symptoms on brain/body) • 4. Detail vs. global; rigid Striving & mastery Emotional & social style (vulnerabilities?) • Anxious; emotional suppression Collaborative Care Involve carers as a bridge to improve socioemotional functioning Carers support emotional functioning by: Moderating isolation Modelling healthy emotion regulation Have to be the regulator when starvation makes it difficult Listen to and understand emotions Collaborative Care Malnutrition/starvation damage Inhibits brain function The very organ you need to get you out of the problem is offline Problems become more complex More rigidity, less flexibility ED takes up more brain space Similarities to autism spectrum traits Collaborative Care “Divide & Rule” ED splits up the family Happens so easily Happens with teams of professionals “Machiavellian rule” don’t negotiate with terrorists Collaborative Care Family as part of the solution Working together Step out of ED traps Collaboration, shared understanding, shared skills Care for self, regulate emotion, reduce accommodation, reduce disagreement and division Provide skills for change Compassion, positive communication, behaviour change skills Collaborative Care Carers emotionally driven behaviours Accommodating – fear, avoid anger Enabling – fear, shame, disgust Calibration – avoid anger, jealousy Collaborative Care Parental avoidance Concern for child’s anxiety Avoid conflict by not challenging food rituals, by reducing portion sizes, etc. Accommodation Impacts all family behaviours A form of avoidant coping Short-term decrease in distress for both parent and child Reinforces behaviour Accept: food & meal rituals, safety behaviours (e.g. exercise), OCD behaviours w/reassurance, competition with other family members Collaborative Care Enabling Try to protect the person and family from consequences of ED Clean up kitchen/bathroom Cover up for lost food or money (e.g. stealing) Give money or resources to allow behaviour (e.g. binge foods) Make excuses for person with family, friends, and work Collaborative Care Calibration/competition Others have to eat with the person Person compares themselves to other family members, especially siblings (e.g. twins) Enlists sibs in enabling behaviours Competes to eat less, exercise harder, etc. Judge their success/failure by other family members Person gets angry with others doing things he/she wants to do Pressures others to engage in similar behaviours (e.g. binging) Share the blame Collaborative Care Food exposure Similar to anxiety treatment Accept that anxiety will be present Understand rationale – make new memories w/food Extinction is context dependent – practice, practice, practice! Learning that the sky won’t fall down Identify & challenge safety behaviours Laddering – one rung at a time Need to eat is non-negotiable Collaborative Care Collaborative care Try to involve all family members (e.g. colluding) Encourage families to care for themselves and model good emotional regulation strategies Help families develop a strong alliance Teach families to reduce expressed emotion (hostility, criticism, over-protection) and accommodating behaviours Teach families effective communication and behaviour change strategies Collaborative Care Communication skills (MI) Empathy – reflective listening Explore discrepancies between values and behaviour Support self-efficacy re. confidence to change Sidestep resistance w/empathy and understanding Not avoiding, not arguing Don’t get defeated if person lashes out Four day skills training workshop Regulated Psychotherapy Until this year, psychotherapy was unregulated 73 Early Steps 1990’s or earlier Psychologists asked the Province for exclusive right to the practice of psychotherapy 74 Stakeholder Consultation The Province undertook an early stakeholder consultation and drafted legislation in the 1990’s. It was flawed and did not proceed 75 New Consultation 2000’s The Province tried again OAMFT got on the bandwagon and actively lobbied for MFT inclusion Psychotherapy Act 2007 76 disease or disorder as the cause of symptoms of the individual in circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that the individual or his or her personal representative will rely on the diagnosis. 2. Performing a procedure on tissue below the dermis, below the surface of a mucous membrane, in or below the surface of the cornea, or in or below the surfaces of the teeth, including the scaling of teeth. 3. Setting or casting a fracture of a bone or a dislocation of a joint. 4. Moving the joints of the spine beyond the individual’s usual physiological range of motion using a fast, low amplitude thrust. 5. Administering a substance by injection or inhalation. 6. Putting an instrument, hand or finger, i. beyond the external ear canal, ii. beyond the point in the nasal passages where they normally narrow, iii. beyond the larynx, iv. beyond the opening of the urethra, v. beyond the labia majora, vi. beyond the anal verge, or vii. into an artificial opening into the body. 7. Applying or ordering the application of a form of energy prescribed by the regulations under this Act. 8. Prescribing, dispensing, selling or compounding a drug as defined in the Drug and Pharmacies Regulation Act, or supervising the part of a pharmacy where such drugs are kept. 9. Prescribing or dispensing, for vision or eye problems, subnormal vision devices, contact lenses or eye glasses other than simple magnifiers. 10. Prescribing a hearing aid for a hearing impaired person. 11. Fitting or dispensing a dental prosthesis, orthodontic or periodontal appliance or a device used inside the mouth to protect teeth from abnormal functioning. 12. Managing labour or conducting the delivery of a baby. 13. Allergy challenge testing of a kind in which a positive result of the test is a significant allergic response. 1991, c. 18, s. 27 (2); 2007, c. 10, Sched. L, s. 32. Note: On a day to be named by proclamation of the Lieutenant Governor, subsection (2) is amended by the Statutes of Ontario, 2007, chapter 10, Schedule R, subsection 19 (1) by adding the following paragraph: 14. Treating, by means of psychotherapy technique, delivered through a therapeutic relationship, an individual’s serious disorder of thought, cognition, mood, emotional regulation, perception or memory that may seriously impair the individual’s judgement, insight, behaviour, communication or social functioning. 77 Almost, but not quite, entirely unlike tea… The authorized act is not yet in force The practice of psychotherapy is now restricted The College regulates the practice of psychotherapy 78 Psychotherapy Act Restricted titles 8. (1) No person other than a member shall use the title “psychotherapist”, “registered psychotherapist” or “registered mental health therapist”, a variation or abbreviation or an equivalent in another language. 2009, c. 26, s. 23 (4). Representations of qualifications, etc. (2) No person other than a member shall hold himself or herself out as a person who is qualified to practise in Ontario as a psychotherapist, registered psychotherapist or registered mental health therapist. 2009, c. 26, s. 23 (4). Offence 10. Every person who contravenes subsection 8 (1) or (2) is guilty of an offence and on conviction is liable to a fine of not more than $25,000 for a first offence and not more than $50,000 for a second or subsequent offence. 2007, c. 10, Sched. R, s. 10. 79 What this means As of April 1st of this year You cannot call yourself a “psychotherapist” unless you belong to the College For a limited time, you can still practice psychotherapy without a license (as long as you don’t say that you are a psychotherapist or qualified to practice psychotherapy) 80 Who can practice psychotherapy? Doctors Nurses Social Workers Occupational Therapists Psychotherapists 81 Further information www.crpo.ca Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991, SO 1991, c 18 Psychotherapy Act, 2007, SO 2007, c 10, Sch R 82 Professional Associations E.g. OAMFT/AAMFT, OASW, OMA Support their members Meeting places Educational events Insurance discounts Do not regulate except to define who is and who is not a member (e.g. may have a Code of Ethics) 83 Colleges E.g. CRPO, OCSWSSW, CPSO Protect the public Regulations Restrictions Penalties Self-regulated Run by members of the profession 84 You must belong to a College You should belong to an Association Friends, support, fun, insurance The Association will help you practice within the College’s guidelines! 85 Questions about the final paper 86 Break 87 Final Evaluation and Closing Goodbye! Remember that papers are due next year! Late penalty, 2% per day. Please email your final paper to carl@mftsolutions.ca or williamcorrigan@rogers.com on or before January 4, 2016 by 5:00 p.m. Eastern Time Don’t worry, be happy! 88