StubHub's Innovation Strategy

advertisement

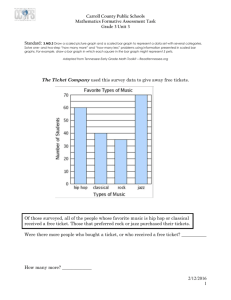

THE TUCK SCHOOL AT DARTMOUTH StubHub’s Innovation Strategy Taylor Bowman, Mike Cwalinski, Philip McDonnell, Fred Schwarz Professor Adner, Entrepreneurship and Innovation Strategy November 12th, 2011 US ticket industry in the year 2000 Ticketmaster circa the year 2000 is a near monopoly in the ticket space. However, even with this monopoly, the industry was not excessively profitable due to extremely low barriers to entry. These low barriers to entry and significant supplier power (event promoters), required Ticketmaster to offer very attractive terms in exchange for exclusive relationships with event venues. This aspect of the industry allowed Ticketmaster to survive numerous anti-trust lawsuits, including one brought by the band Pearl Jam in the early 90s. In 2001, Ticketmaster, which accounted for virtually all offline ticket sales, had $580M in revenues and an operating profit of $114M. At this time, almost all event tickets are issued in paper form. Ticketmaster had begun experimentation with electronic tickets but this was not widespread. As a result, the traditional way to buy tickets for an event on a secondary market is to find illegal scalpers outside of the stadium and physically exchange the tickets. There were two primary issues with this process from the perspective of end consumers, the first was fraud and the second was the legality of the process. Fraud was extremely widespread in the scalping process and it was difficult for consumers to protect themselves since purchasing tickets for greater than face value is illegal. There are 38 states that have laws preventing scalping when it is physically near the stadium. The remaining 12 states have various legal constraints on the exchange of tickets for events. Strategic players in this space are: Customers - both individual event and season ticket purchasers Teams, venues and event promoters – suppliers to the ticket market Ticketmaster – which is the primary ticket broker in the market Ticket Brokers/Scalpers – try to purchase premier event tickets and resell them to consumers at a premium Other secondary marketplaces – in 2000 these had not taken off yet Legislators – who have significant impact on the market through regulations Below is an ecosystem map of the industry circa the year 2000: Figure 1 - Ticket Industry Ecosystem Circa 2000 Launch of LiquidSeats In 2001, Jeff Fluhr was a first year student at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and came up with an idea for an online marketplace where consumers could buy and sell surplus tickets. Online ticket sales made up less than 10% of the market at this time. He believed so strongly in the idea that he dropped out of school to pursue the opportunity and launched LiquidSeats. The original market entry strategy was to build an online ticket transaction system that major websites like MSN could use to sell tickets on their site. LiquidSeats also launched their own website utilizing the transaction system called StubHub but it wasn’t until 2003 when Fluhr began using Google’s advertising service that he realized how much more revenue could be generated through operating their own site. The StubHub Era StubHub differentiated itself from other secondary markets like EBay by not charging listing fees and instead charging a 15% commission to sellers and 10% commission to buyers. The company took no inventory, which reduced its risk. However, this meant that StubHub had to be creative about driving volume to its site. It pursued multiple partnerships to drive volume. The first approach was to form a partnership with EBay to allow StubHub tickets to be listed in EBay search results. However, StubHub quickly began competing directly with EBay and the partnership was dissolved. The major approach that StubHub took to drive volume was to form partnerships with ticket originators. In return for promoting StubHub to season ticket holders of sporting events, StubHub would split commissions on any season ticket holder sales. That approach changed in the mid-2000’s and instead of a commission based partnership; StubHub offered a flat payment for promotion to season ticket holders as well as their contact info. At this point, the secondary ticket markets were facing a number of technological and organizational issues. The major technological issue for the secondary markets was verifying ticket authenticity. This is something that Ticketmaster was able to offer and posed a specific challenge to a company like StubHub. To address this issue, StubHub attempted to authenticate the identity of users using technology like Verisign. They also guaranteed fraudulent purchases to reduce consumers concerns. From an organizational perspective, StubHub faced a significant logistical challenge dealing with paper tickets. They needed to ensure the right ticket got the right customer and also that tickets were received by customers in time for the event. In light of the fraud and logistical challenges, customer service was also a difficult problem for StubHub. Many tickets were counterfeit and StubHub spent a lot of effort to make buyers in the marketplace feel supported against potential counterfeits. They operated two call centers in the US, one on each coast. StubHub has the ability to dis-intermediate an industry that is deeply backwards. It has historically been rife with counterfeit tickets, consumer legal dilemmas, and other uncomfortable situations. The ticket market overall is worth in excess of $40B. In addition to the standard, consumer-to-consumer secondary market there is a rich opportunity for sports teams and other venues to engage in yield management and use StubHub to liquidate unsold inventory. Given that a team’s marginal cost for additional tickets is nearly zero, you begin to see the profound opportunity StubHub holds. Competitive landscape Reviewing the competitive landscape in both StubHub’s early years and today is a critical step in understanding what ticket customer “problems” were not being solved, allowing StubHub to enter the secondary market for event tickets with what turned out to be an innovative solution. There are two broad categories of competition that StubHub faced at its founding and continues to face today. The first is substitutes. Most of these were formed before StubHub’s creation, attempting to serve the secondary market for event tickets in different ways. For the most part, these forms were suboptimal. The second competitive bucket was websites trying to execute using the same online, consignment market place model as StubHub. When StubHub was formed, none of these players had created any scale. We can examine substitutes for StubHub in order of their invention. The clear originator was the “street corner scalper”. His model is very simple; he builds inventory by purchasing tickets from sellers with buyer’s remorse or from the ticket originator. The scalper obviously hopes to make money on the buy-sell price spread. A strength of the scalper is that he provides liquidity to the market by taking an inventory position. This gives increased certainty of a resale to a potential seller willing to take the inconvenient step of going to the arena to sell a ticket for an event they may not plan to attend. An inability to get to the event may be the very reason the seller is not attending in the first place. Weaknesses of the street corner scalper model include the fact that, although they can reliably be found at any event, they are not all on one street corner. This creates pricing inefficiency because the market makers are not truly in one place, competing against each other. These realities can limit inventory for the buyer, as the inventory of secondary market tickets for the event is held by a fragmented group of market makers. Different scalpers may be holding different types of inventory, such as better seats. Therefore, the buyer cannot compare the quality of the each seller’s inventory and their associated price against the inventory of a different seller. Fraud is also a significant issue when purchasing from a street corner scalper. This risk invariably hangs over the profession and consumers that purchase from scalpers. This drives down prices due to the lack of a clearinghouse providing a guarantee. The second major substitute to emerge was eBay. eBay became the go-to online marketplace in the late 1990s. It brought together buyers and sellers of thousands of different products, and naturally it became an attractive option for those who wanted to buy and sell event tickets. However, it was not a ticket specific site and as a result, inventory breadth was not reliably found. eBay management was not also focused on tickets given the vast amount of products traded on the site. Furthermore, eBay had no relationships with the ticket originators, and missed opportunities to form partnerships that would increase inventory. Another weakness was eBay’s lack of a guarantee of quality and delivery time. It must be remembered that event tickets have a finite useful life and so timely delivery was absolutely critical. eBay’s time consuming auction model further added to the potential expiration issue. However, eBay did provide an online marketplace that sellers and buyers could use remotely, unlike the street corner scalper. The ticket inventory eBay did have was easily compared regarding price and seat quality which differed from the many street corner scalpers standing on the many street corners. The third type of replacement was the online ticket broker. Like the scalper, the online ticket broker provides liquidity by holding inventory. If a seller finds the price offered them acceptable, they can immediately offload their event ticket to a ticket broker. But the weakness of online ticket brokers was primarily their fragmentation. Online ticket brokers had little scale, making it difficult for buyers to compare prices. The expense of holding inventory prevented online ticket brokers from creating a broad selection. This limited the attractiveness of these sites to end consumers. In addition to substitutes, there were online sites trying to compete on a consignment model similar to StubHub’s. However, these sites did not manage to build the scale to crack the “chicken and the egg” problem. It is difficult to bring in potential buyers without an interesting breadth and reliability of tickets for sale. At the same time, it is difficult to bring in an interesting level of potential sellers without an adequate level of buyers to move their inventory quickly and at attractive prices. This is the chicken and the egg challenge. StubHub solved a number of problems for buyers and sellers. Relative to the scalper, the site carried a breadth of tickets that could be compared to each other, driving pricing efficiency. StubHub also provided a quality guarantee that decreased risk for consumers. In comparison to EBay, StubHub was focused on a very narrow product set, which allowed it to have a more targeted marketing message. StubHub’s clear messaging allowed it to create enough network effects to bring in buyers and sellers. Although StubHub does not provide immediate liquidity by purchasing inventory, StubHub’s breadth of listed tickets made it the go to spot for those searching for event tickets. The large amount of buyers therefore eliminated the need for a central source of liquidity. In comparison to direct competitors, StubHub’s execution was superior. StubHub created partnerships with event originators like MLB and various NFL teams to be their “official ticket resellers”. This brand recognition drove consumer confidence in the site and compounded the network effect needed to solve the chicken and the egg problem. Entry strategy: innovation phase StubHub was a late entrant to the dot com boom. Founded in 2000, StubHub did not get much traction in the market until 2003. This lack of progress was partly due to the fact that Eric Baker and Jeff Fluhr did not graduate from Stanford GSB until the spring of 2001. Initially StubHub existed as LiquidSeats and then later changed over to be called StubHub. In the beginning the organization was primarily focused in the Bay Area and targeted the local season ticket holders of the Oakland Raiders. Initially, StubHub sought out to prove their concept by engaging local ticket brokers and getting them signed up on StubHub’s platform. This people heavy strategy limited StubHub’s initial progress, and it was very slow going from 2000-2002. StubHub’s leaders initially described their site as a “Ticket Service Provider technology, an online database engine designed to connect after-market ticket buyers and sellers.” In the beginning StubHub saw its service as a widget that would be embedded within other websites. StubHub imagined that there would be thousands of small “stubhubs” all across the web and that stubhub.com would be the main example of how to run such a system. In 2001, StubHub signed their first team, the Phoenix Coyotes. While this partnership wasn’t a homerun by any means, it gave StubHub the opportunity to demonstrate value addition to a real sports team. As part of the deal, the Coyotes sent a letter to their season ticket holders instructing them that they could sell their extra tickets through the StubHub web site. At the time, StubHub was charging a 10% fee to the buyer and a 15% fee to the seller, therefore netting a total 25% commission on every ticket sold. After this proof of concept with the Coyotes, the StubHub team was able to drum up angel funding from locals in Silicon Valley, including Steve Young, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback. This additional investment allowed Baker and Fluhr to ramp up their operations. With decent market traction and initial funding in the bank from early angels, StubHub began to pour money into advertising across a number of different mediums, making investments primarily in radio and online ads. On the internet advertising, StubHub focused on pay-per-click campaigns on Google and Yahoo, but also purchased banner ads on most major internet sites. This campaign was centered on selling the message that StubHub was a “fan to fan exchange” stating that “fans supply the ticket and set the price.” Additionally, the founders used the funds to ramp up the StubHub team. They focused their spending on public relations, marketing, and partnerships. The goal was to build awareness of StubHub in the general American population and to obtain access to season ticket holders with the help of sports teams. StubHub’s early focus on partnerships seems prudent on the surface; however, with only a very small percentage of professional sports teams onboard, it is questionable if StubHub’s multi-year headcount spend on partner acquisition was smart at such an early stage. However, by 2003 StubHub had begun to make headway both in the Bay Area and beyond. By this time they were starting to approach sports teams about the idea of partnering with greater scale. According to Stanford’s alumni website, “sports franchises traditionally have been wary of secondary ticket sales and their shady reputation…but Baker and Fluhr argued that teams that told their fans about StubHub would boost attendance.” Based on this new pitch, the Arizona Diamondbacks, New York Jets, and the Stanford and University of California at Berkeley athletic departments “jumped at a way to put more fans in the stands—and more money in their coffers from additional concession sales.” The StubHub team also pursued other channels to acquire tickets, including charity auctions of concert tickets. Musicians such as Christina Aguilera, Seal, and Jewel donated front-row tickets that were auctioned off through StubHub and sent the proceeds to the artists’ preferred charity. Early partnerships: teams and brokers One question that arises as we consider partnerships is the question of where all the tickets were coming from. Despite the fact that StubHub had relatively few team partnerships early on, they were still doing well in most markets with plenty of ticket inventory. This early ticket volume was driven by ticket brokers. It is estimated that at least 80% of StubHub’s tickets originate with ticket brokers. Typically ticket brokers maintain data feeds of their current tickets in order to list them on online auctions and their own websites. StubHub developed a backend interface that would take these feeds, mark them up 15%, and then sell the tickets to consumers shopping on StubHub’s website. This integration went deeper than just cross-listing tickets, however. StubHub supplied their brokers with official StubHub ticket envelopes and materials to place in the FedEx envelopes that were shipped to customers. This gave tickets purchased from ticket brokers the same consistent feel as a traditional StubHub intermediated ticket sale. This also improved the timelines at which StubHub and its brokers could ship the tickets since the tickets did not need to be shipped to StubHub first under this process. Logistics As mentioned above, many of StubHub’s early tickets came from ticket brokers who had an inventory of StubHub envelopes and other packaging materials that would allow them to drop tickets in the mail via FedEx pick-up. These FedEx envelopes’ postage would then be paid directly by StubHub. For consumers that wanted to sell their tickets, they were required to send their tickets into StubHub directly. This process was time consuming, but very important. Once the tickets were at StubHub’s distribution center, StubHub would then put the tickets into FedEx envelopes and await purchase via online or their call centers. This consignment model gave StubHub the ability to try and generate revenue at very little risk. StubHub could also potentially list the tickets before they physically had them at the distribution center, although we have not found any documented evidence of them doing this. The FedEx delivery gave StubHub’s tickets a practical safety from theft, but it also gave them a high-end feel for consumers. In a market rife with scams, fake tickets, and other problems this seemingly high-end experience was very welcome to consumers. One drawback of StubHub’s strategy of relying on ticket brokers for fulfillment is the inability to completely control quality and ensure ticket authenticity and delivery. In our research we found numerous examples in comments and blogs about individuals who never received tickets or had problems with their tickets once at the event. While StubHub was not able to verify all tickets early on, they later developed backend systems to better authenticate tickets from brokers and fans. StubHub also refused to continue business with ticket brokers who had sold fraudulent tickets through StubHub or not delivered tickets in time to customers. StubHub maintained two call centers to deal with customer complaints, and StubHub compensated fans when any problems arose. This later took the form of StubHub’s current FanProtect Guarantee. Given the volume of tickets sold through StubHub, it has been impossible to prevent all risks to customers, but StubHub has attempted to mitigate as much risk as possible. StubHub’s ecosystem, post innovation StubHub’s initial innovations of creating an online secondary ticket marketplace, establishing logistics practices to handle ticket volume, and its partnership and entry strategy brought StubHub success and growth in its early years. StubHub changed the ticket distribution ecosystem dramatically. After StubHub achieved scale in the early part of the decade, the ticket distribution ecosystem looked as follows: Figure 2 - Ticket Industry Ecosystem Circa 2003 and beyond StubHub was able to be successful in several ways, both from a supply and demand side. For end customers, StubHub offered a much more convenient and safe purchasing model than any of the previous ticket resellers in the ecosystem. End customers faced risks of counterfeit tickets or fraud when purchasing from traditional street scalpers, ticket brokers, or auction sites such as eBay. Through its verification processes and FanProtect Guarantee, StubHub was able to mitigate this risk for consumers and compensate them quickly and fairly when something did go awry. Similar to iMotors, StubHub internalized the risk to its customers, which dramatically increased their willingness to purchase through StubHub versus other resellers. The convenience of StubHub’s online model was also critical for success; consumers could now purchase tickets anytime of the day. Furthermore, StubHub’s national model appealed to consumers who traveled or were fans of multiple sports. Finally, StubHub offered a sizable selection of tickets that traditional ticket brokers and scalpers simply could not compete with. From a supply side, StubHub offered significant value to ticket sellers, whether they were fans or ticket brokers. StubHub provided a liquid marketplace that drew national traffic, similar to eBay. But unlike eBay’s auction format, StubHub allowed sellers to set their own prices, and change them at any time. Savvy sellers could manage prices over time in order to improve profits. In fact, StubHub actively facilitated this by offering sellers pricing statistics on similar tickets at comparable events. In this way, StubHub used its scale and large quantity of historical transaction data to add value to sellers. StubHub also guaranteed payment for all fulfilled orders. This decreased the risk for a key player in the ecosystem, the original ticket holder (often a season ticket holder), and removed a barrier to selling to StubHub, which further increased the supply of tickets available to StubHub. These advantages allowed StubHub to grow at a rapid pace, achieving $199 million in revenue in 2005, and ranking 8th on the 2006 Inc. 500, Inc. magazine’s annual list of the nation’s fastest growing companies. But StubHub’s early success with its new business model did not go overlooked by Ticketmaster and other competitors. Prior to StubHub and other online resellers such as eBay, RazorGator, and TicketsNow, Ticketmaster was essentially the only legitimate option for many fans looking to buy tickets. But as the new competitors grew, Ticketmaster became aware of how much money was available in the ticket reselling market. According to StubHub spokesman Sean Pate in 2006, Ticketmaster “was envious of the prices that tickets are being sold for on the secondary market.” For every event that was sold out through Ticketmaster, ticket resellers like StubHub would often re-offer the tickets at higher prices. Ticketmaster and the ticket originators missed out on all of this aftermarket cash. Ticketmaster responds Ticketmaster responded by developing its own ticket resale site, TicketExchange, in 2004. This was an apparent attempt to compete head to head against StubHub and other online resellers. TicketExchange attempted to differentiate itself from these competitors by offering 100% guarantees of ticket authenticity, based on officially partnering with sports teams and selling tickets directly from season pass holders’ accounts. However, this business never achieved traction with consumers, for two primary reasons. First, online resellers had already established their positions in the market and in consumers’ minds. StubHub in particular was adept at marketing and had built a strong brand and reputation. Secondly, we suspect that StubHub customers were already satisfied with StubHub’s FanProtect Guarantee. TicketExchange’s main attempts at differentiation—“officialness” and 100% authenticity guarantees—were criteria likely viewed as thresholds by consumers, rather than absolute benefits. If StubHub’s FanProtect guarantee met the threshold required for this criterion, then TicketExchange simply focused their differentiation efforts in the wrong place. In 2005, TicketExchange sold less than 10% of the ticket volume as StubHub, and the business never achieved a significant share of the market. In 2008, Ticketmaster would continue its pursuit of the secondary market by purchasing TicketsNow, a leading ticket reseller, for $265 million. At the time of purchase, TicketsNow was approximately half the size of StubHub. This acquisition has had more success over time, but Ticketmaster has also been plagued with criticism of misdealings between the primary market Ticketmaster site and the secondary market TicketsNow site. By participating in both the primary and secondary markets, Ticketmaster has opened itself up to allegations that it is merely shifting tickets from Ticketmaster to TicketsNow in order to sell them at dramatically higher prices, and therefore capture a larger portion of the value created in the marketplace. StubHub partnership development During the mid-2000s, StubHub expanded its business development efforts to include larger and larger partners in the form of individual sports teams and various music venues. While fans and ticket brokers have always been able to sell tickets for nearly any event through StubHub, StubHub realized the tremendous value it could create through official partnerships with ticket originators. StubHub actively signed on partners in order to drive more fans to StubHub’s website, resulting in a more liquid ticket marketplace and more sales revenues. In a typical deal, partner teams advertised for StubHub on their own websites, proclaiming StubHub the “official ticket reseller of team X” and directing fans looking for secondary market tickets to StubHub. In return, StubHub provided lump sum yearly payments, often in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. StubHub increased competition in the reseller marketplace and provided sports teams the ability to advertise that they had the fans best interests in mind regarding security and legitimacy of secondary market tickets. These official partnerships went a long way toward legitimizing StubHub as a safe and legal way to trade tickets. Official endorsement was very important within an ecosystem where the more traditional substitute, a scalper in a trench coat standing on a corner, had very little trust with the consumer. In most cases these official partnerships allowed StubHub to provide an additional benefit to consumers by linking its backend IT systems with those of its partners; this allowed ticket buyers to download their tickets electronically immediately after purchase. In 2007, StubHub signed a five year partnership agreement with Major League Baseball, StubHub’s largest deal to date. While financial terms were not disclosed, StubHub agreed to pay the league for sponsorship rights. In a first for StubHub, the two entities also agreed to share a percentage of revenue from secondary market sales. A key stipulation of the deal was that if an MLB team wants to allow reselling of tickets online, they can only do so through StubHub. This deal is interesting for two key reasons. First, StubHub received a significant amount of value by gaining monopoly status as the official reseller of MLB. Secondly, the revenue sharing aspect provokes key questions concerning the deal. Revenue sharing aligns incentives between the partners, by providing MLB a major incentive to drive as much traffic to StubHub as possible. But it may also indicate a unique arrangement not disclosed in the public terms of the agreement. Could it be that MLB is providing StubHub primary market tickets to sell as secondary market tickets? An arrangement like this would add a tremendous amount of value to both StubHub and MLB. By selling primary tickets through StubHub’s secondary marketplace, MLB could engage in price discrimination on a large scale. Rather than lose out on all the value created in the secondary market when tickets sell for greater than face value, MLB could keep a large portion of this cash. Furthermore, this presents an opportunity for MLB teams to engage in yield management and provide them with a secondary channel to liquidate unsold inventories. Given a 162 game season and overcapacity at many MLB stadiums, these unsold inventories are often sizeable. Selling this excess inventory through StubHub would allow MLB to capture the entire consumer surplus for consumers whose value was greater than the teams’ marginal costs. Similar to movie theaters and airlines, the marginal costs of tickets for sporting events or concerts are nearly zero. Importantly, MLB could do this without altering the face value of tickets being sold in the “true” primary market. Furthermore, StubHub’s highly secure online environment and guarantee that buyers and sellers will never communicate or interact means that consumers would never know they were buying tickets directly from MLB. Arrangements of this nature would dramatically increase the value to official sports team and music venue partners by allowing them to effectively price discriminate; in return, StubHub would gain volume and likely be able to negotiate a share of the additional value captured by its partners. Partnership arrangements like this have never been publicly disclosed, either because they don’t exist or due to expectations of severely negative fan reactions if exposed, similar to criticisms of Ticketmaster’s relationship with TicketsNow. Either way, StubHub and its partners must clearly see the huge value these arrangements would create, and be itching to get into this game if they are not there already. Value Chain Risks StubHub faced, and continues to face, several value chain risks from other players in the ecosystem. While ticket scalping—selling tickets for prices above face value—is legal in 38 states, changes to the law could negatively impact StubHub’s reselling business. However, we have chosen to not focus on this risk explicitly for two reasons. First, the vast majority of legislation from lawmakers in the last decade has served to enable StubHub’s business, not constrain it by placing further restrictions on ticket reselling. Secondly, StubHub’s official sports team and music venue partners have lobbied strongly on StubHub’s behalf, both to lawmakers and directly to consumers in the form of public relations campaigns. Despite counter-lobbying by Ticketmaster, which has seen its business eroded by StubHub, all signs point to StubHub continuing to gain legitimacy in the eyes of lawmakers and consumers. StubHub’s reselling model is clearly here to stay. That said, value chain risks are present, and these are summarized below: Figure 3 - Value Chain Risks Conclusion: StubHub today and lessons learned In 2007, eBay purchased StubHub for $310 million. At the time, StubHub was moving an estimated $400 million in ticket sales annually through its website. StubHub was the number one player in the secondary ticket market and was the first to truly crack “the chicken and the egg” problem. eBay believed that StubHub would benefit from its established community of users while offering buyers a greater selection. For example, on eBay’s website today they show tickets listed on eBay right next to similar tickets listed on StubHub. It should also be noted that eBay saw the acquisition as a way to turn a leading competitor into a friend. By most estimates the acquisition has been a positive one for eBay. It has been reported that StubHub moved $1 billion worth of event tickets in 2010, representing significant growth. However, there are clouds in the secondary ticket market sky. The latest threat to StubHub is Ticketmaster’s roll out of paperless tickets. These tickets can be redeemed on a phone and many are marked as strictly non-transferable, requiring the original purchaser to show a photo ID to use the tickets, similar to airline tickets. The paperless aspect of these tickets allows the venue and Ticketmaster to strictly enforce non-transferability. Ticketmaster argues this is more convenient for ticket holders, while StubHub argues this removes the consumer’s right to transfer a good that they paid for. StubHub argues that events will be hurt when fewer seats are filled, leading to less popcorn, parking, and T-shirts sold. Both organizations have launched significant lobbying efforts targeting consumers and the highest levels of the national government. Despite StubHub’s uncertain future, there are clear lessons to be learned from its rise. The first lesson is that when innovating in an ecosystem, firms must ensure that their business is not destroying significant value for critical players with substantial control. Rather than destroy value for ticket originators, StubHub created value for key stakeholders such as Major League Baseball and other sports teams, and established partnerships with these organizations. However, StubHub has not found a way to make peace with Ticketmaster, another key player in the ecosystem, and Ticketmaster continues to present itself as a significant threat to StubHub. A second key lesson concerns marketplace innovation. To solve the chicken and the egg problem, a market must solve multiple problems for both buyers and sellers—not just one. Compared to its contemporary competition and the available substitutes, StubHub solved the problem of location convenience, guaranteed quality, comparable pricing, and a central marketplace. Third, if there is seller and buyer anonymity, the marketplace gains an opportunity to partner with ticket originators and allow them to engage in price discrimination. Ticket originators could sell some tickets above face value and some below in order to optimize revenue and capture additional consumer surplus. The anonymity that a market like StubHub’s can offer helps prevent consumer outcry at blatant price discrimination, allowing sellers to maximize profits. Regardless of StubHub’s future, StubHub provides an illuminating example of the birth of an innovative and successful online marketplace. SOURCES Armstrong, Drew; Inc.; “Competition Heats Up in the $10 Billion Ticket Market”; October 9 th, 2006; http://www.inc.com/articles/2006/10/tickets.html Arrington, Michael; Tech Crunch; “eBay's Place in the Dirty World of Ticket Scalping”; Januarty 10th, 2007; http://techcrunch.com/2007/01/10/eBays-place-in-the-dirty-world-of-ticketscalping/ Belushi, online commenter; Don’tCostNothing.com; “StubHub: The biggest fraud in the ticket business”; March 9th, 2007; http://dontcostnothing.wordpress.com/2007/03/09/stubhub-the-biggest-fraud-in-the-ticketbusiness/ Bloomberg Businessweek; “Ticketmaster: Still Stuck on CitySearch”; April 4th, 2001; http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/apr2001/nf2001044_610.htm Branch Jr., Alfred; Ticket News; “StubHub! and MLB Strike Precedent-Setting Secondary Ticketing Deal”; August 2nd, 2007; http://www.ticketnews.com/news/StubHub-and-MLB-StrikePrecedent-Setting-Secondary-Ticketing-Deal8227 Broache, Anne; CNET News; “Ticketmaster sues eBay's StubHub over sales tactics”; April 20th, 2007; http://news.cnet.com/2100-1030_3-6178001.html CNNTech; “LiquidSeats helps fill the house, sans scalping”; December 14th, 2000; http://articles.cnn.com/2000-12-14/tech/liquid.seats.tickets.idg_1_ticket-service-providerliquidseats-stubhub-com?_s=PM:TECH eBay press release; “eBay To Acquire Online Tickets Marketplace StubHub”; January 10th, 2007; http://investor.eBay.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=225333 Fried, Josh; Stanford Magazine; “Admit Two: StubHub’s founders want to take the worry out of getting close seats”; http://www.stanfordalumni.org/news/magazine/2004/novdec/dept/bright.html Funding Universe; Ticketmaster Group, Inc; http://www.fundinguniverse.com/companyhistories/Ticketmaster-Group-Inc-company-History.html Lee, Se Young and Bruce Mohl; The Boston Globe; “MLB, StubHub ink resale deal”; August 2 nd, 2007; http://www.boston.com/business/globe/articles/2007/08/02/mlb_stubhub_ink_resale_deal/ Razorgator; http://www.razorgator.com/ Schonfeld, Erick; Tech Crunch; “Ticketmaster Buys Online Scalper TicketsNow for $265 Million”; January 15th, 2008; http://techcrunch.com/2008/01/15/ticketmaster-buys-online-scalperticketsnow-for-265-million/ Sisario, Ben; The New York Times; “Scalping Battle Putting ‘Fans’ in the Middle”; July 20 th, 2011; http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/21/business/media/scalping-battle-putting-fans-in-themiddle.html?pagewanted=all Stecklow, Steve; The Wall Street Journal, as republished in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; “StubHub’s got a ticket to ride”; January 17th, 2006; http://www.postgazette.com/pg/06017/639372-28.stm StubHub; http://www.stubhub.com/ Ticketmaster; http://www.ticketmaster.com/ Ticketmaster and TicketsNow; http://www.ticketmaster.com/ticketsnow TicketsNow; http://www.ticketsnow.com/ The Washington Post, as republished on StubHub’s Media Coverage webpage; “'Paperless ticketing' aims to thwart scalping at concerts, sports events”; July 5th, 2010; http://www.stubhub.com/media-coverage-detail?articleId=11011 Wolverton, Troy; CNET News; “Ticket market meets its digital future”; May 21 st, 2002; http://news.cnet.com/Ticket-market-meets-its-digital-future/2100-1017_3-918746.html?tag=mncol;txt