Chapter 9

advertisement

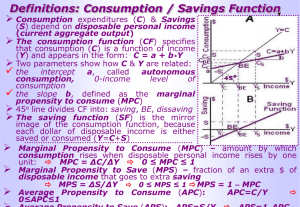

9 Basic C HAPT E R Macroeconomic Relationships The Income-Consumption and Income-Saving Relationships • Disposable income is the most important determinant of consumer spending (consumption). • What is not spent is called saving. • Disposable Income (DI) = C + S S = saving Saving = DI – C • • • Note: (disposable income in Kuwait = personal income since there is no income tax) A 45-degree line: each point on the line is equidistant from the two axes. Therefore, represents all points where consumer spending is equal to disposable income. • Or each point represent a situation where; C + S = DI • Any vertical distance from the horizontal axis to the 450 line measures DI Income and Consumption 10000 9000 Consumption (billions of dollars) 05 45° Reference Line C=DI 8000 04 03 01 7000 02 00 C 99 6000 Saving In 1992 5000 98 97 96 95 94 93 92 4000 3000 83 2000 84 88 87 86 85 91 90 89 Consumption In 1992 1000 45° 0 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 Disposable Income (billions of dollars) Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis Consumption Schedule • Reflects the direct consumptiondisposable income relationship • Note: households tend to spend a larger proportion of a small DI than of a larger DI. The saving schedule • Reflects the direct relationship between S and DI • Saving is a smaller proportion of small DI than of a large DI • Dissaving: when households consume more than their DI. They do that by liquidating their wealth (assets) or by borrowing Consumption and Saving Schedules Disposable Income 350 370 390 410 430 450 470 490 510 530 550 Consumption 360 375 390 405 420 435 450 465 480 495 510 Saving -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 CONSUMPTION AND SAVING Consumption SAVING C Consumption schedule C DISSAVING o 45 MPC = Slope of C o MPC + MPS = 1 Saving Disposable Income DISSAVING Saving schedule MPS = Slope of S S SAVING o S Disposable Income Break even income: • The income level at which households plan to consume their entire income, (C=DI). • At break even: Consumption schedule cuts the 450 line. - Saving schedule cuts the horizontal axis . - Saving = zero - APC = 1 - APS = zero Consumption and Saving (1) Level of (2) Output ConsumpAnd tion Income (C) (GDP=DI) (1) $370 (3) Saving (S) (1) – (2) (4) Average Propensity to Consume (APC) (2)/(1) (5) Average Propensity to Save (APS) (3)/(1) $375 $-5 1.01 -.01 (2) 390 390 0 1.00 .00 (3) 410 405 5 .99 .01 (4) 430 420 10 .98 .02 (5) 450 435 15 .97 .03 (6) 470 450 20 .96 .04 (7) 490 465 25 .95 .05 (8) 510 480 30 .94 .06 (9) 530 495 35 .93 .07 (10) 550 510 40 .93 .07 MPC + MPS = 1 (6) Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) Δ(2)/Δ(1) (7) Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS) Δ(3)/Δ(1) .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 .75 .25 MPC and MPS measure slopes Average and marginal propensities to consume and save • Average propensity to consume (APC) is the fraction or % of income consumed APC = consumption/income • Average propensity to save (APS) is the fraction or % of income saved APS = saving/income • Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction or proportion of any change in income that is consumed MPC = change in consumption/change in income • Marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction or proportion of any change in income that is saved MPS = change in saving/change in income Note: • As DI increases; APS rises and APC falls. • APC + APS = 1 • MPC + MPS = 1 Because: ∆DI = ∆C + ∆S Non-income determinants of consumption 1. Wealth: An increase in wealth shifts the consumption schedule up and saving schedule down. Wealth Effects: when assets boast, households feel wealthy, they save less and consumer more, and vice versa. 2. Expectations: Changes in expected future prices or wealth can affect consumption spending today. 3.Real interest rates: Declining interest rates increase the incentive to borrow and consume, and reduce the incentive to save. Because many household expenditures are not interest sensitive – the light bill, groceries, etc. – the effect of interest rate changes on spending are modest. 4.Household debt: Lower debt levels shift consumption schedule up and saving schedule down. But if debt is too high, they will reduce their consumption to pay off some of their loans. Terminology, shifts and stability 1. Terminology: Movement from one point to another on a given schedule is called a change in amount consumed; a shift in the schedule is called a change in consumption schedule. 2. Schedule shifts: Consumption and saving schedules will always shift in opposite directions unless a shift is caused by a tax change (move together). 3. Stability: Economists believe that consumption and saving schedules are generally stable unless deliberately shifted by government action. TERMINOLOGY, SHIFTS, & STABILITY Consumption C1 C0 Increases in Consumption Means… o 45 o Saving Disposable Income A Decrease S0 S1 In Saving o Disposable Income Consumption TERMINOLOGY, SHIFTS, & STABILITY C0 C2 Decreases in Consumption Means… o 45 o Saving Disposable Income S2 An Increase S0 In Saving o Disposable Income Average Propensity to Consume Selected Nations, with respect to GDP, 2006 .80 .85 .90 .95 1.00 United States Canada United Kingdom Japan Germany Netherlands Italy France Source: Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2006 The Interest Rate – Investment Relationship • Investment consists of spending on new plants, capital equipment, machinery, inventories, construction, etc. • The investment decision weighs marginal benefits (r) and marginal costs (i). 1. Expected Rate of Return, r: This is marginal benefit of investment. • Expected Rate of Return = expected profit/cost of capital • If expected profit on a $1000 investment is $100. This is a 10% expected rate of return. Thus, this business would not want to pay more than a 10% interest rate on investment. • Remember that the expected rate of return is not a guaranteed rate of return. Investment carries risk. 2. Real Interest Rate, i: This is the marginal cost of investment (nominal rate corrected for expected inflation) Real interest rate = nominal interest rate – expected inflation • The interest rate represents either the cost of borrowed funds or the opportunity cost of investing your own funds, which is income forgone. • If real interest rate exceeds the expected rate of return, the investment should not be made, example: • If expected rate of return r = 10% • Nominal interest rate = 15% • Inflation rate = 10% • This investment is profitable since • 10% > (i = 15%-10%) 5% • Expected return > real interest rate Investment demand curve Interest rates Expected rate of return 16% 14% 12% 10% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% Cumulative investment 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 Investment demand schedule, or curve, shows an inverse relationship between the interest rate and amount of investment. • As long as expected return exceeds interest rate, the investment is expected to be profitable • if rate of interest is 12%, businesses will undertake all investment opportunities that yield 12% or more. • If rate of interest is less, more investment will be undertaken • If rate of interest is more, less investments will be undertaken Interest Rate – Investment Relationship and interest rate, i (percents) Expected rate of return, r, 16 14 INVESTMENT DEMAND CURVE 12 10 8 6 4 2 ID 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 Investment (billions of dollars) Shifts of investment demand 1. Acquisition, Maintenance, and Operating Costs: Initial costs of capital, operating costs and maintenance affect the expected rate of return – When they fall, prospective investment projects increase (shift to the RHS) – When they increase, prospective investment projects decrease (shift to the LHS) 2. Business Taxes When tax increases, expected (after tax) return decreases, shifts the investment curve to the LHS and vice versa. 3. Technological Change Technological progress (more efficient machines). Technological change often involves lower costs, which would increase expected returns and stimulates investment (shifts the investment curve to the RHS, and vice versa). 4. Stock of capital goods on hand Relative to output and sales, if there is abundant idle capital on hand because of weak demand or recent investment (overstock), expected return on new machines declines (would be less profitable) and investment curve shifts to the LHS and vice versa. 5. Expectations about future economic and political conditions can change the view of expected returns. – Optimistic expectations about the return, shifts the investment curve to the RHS – Pessimistic expectations shifts the investment curve to the LHS Instability of investment Investment schedule is unstable, it shifts upward or downward quite often. Investment is the most volatile component of total spending. Reasons for instability of investment 1. Durability of capital and variability of expectations Within limits, purchases of capital goods are discretionary and therefore, can be postponed. Optimism about future may prompt firms to replace older capital. Pessimism about the future lead to small investment as firms repair old capital. 2. Irregularity of Innovation Technological progress is a major determinant of investment. But major innovations occur quite irregularly. When they happen, they induce vast investments. e.g., the new information technology 3. Variability of expectations Expectations are influenced by: - Current profit levels, - Changes in exchange rates, - Outlook for international peace, - Changes in government policies - Stock market prices…etc 4. Variability of profits: Profits are highly variable. This contributes to the volatile incentive to invest. Also profits are a major source of investment finance (internal source), if they are variable, investment will be instable. Gross Investment Expenditure Percent of GDP, Selected Nations, 2006 0 10 20 30 South Korea Japan Canada Mexico France United States Sweden Germany United Kingdom Source: International Monetary Fund Volatility of Investment Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis 27-33 The Multiplier Effect • Changes in spending ripple through the economy to generate even larger changes in real GDP. This is called the multiplier effect. Multiplier = change in real GDP / initial change in spending. Alternatively, it can be rearranged to read Change in real GDP = initial change in spending × multiplier. Three points to remember about the multiplier: a. The initial change in spending is usually associated with investment because it is so volatile. b. The initial change refers to an upward shift or downward shift in the aggregate expenditures schedule due to a change in one of its components, like investment. c. The multiplier works in both directions (up or down). Rationale: The multiplier is based on two facts 1. The economy has continuous flows of expenditures and income—a ripple effect—in which income received by Ali comes from money spent by Ahmad. Ahmad’s income, in turn, came from money spent by Said, and so forth. 2. Any change in income will cause both consumption and saving to vary in the same direction as the initial change in income, and by a fraction of that change. a. The fraction of the change in income that is spent is called the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). b. The fraction of the change in income that is saved is called the marginal propensity to save (MPS). THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT Multiplier Change in GDP Change in Real GDP = Initial Change in Spending = Multiplier x initial change in spending For Example… THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT (2) (3) Change in Change in (1) Saving Change in Consumption Income (MPC = .75) (MPS = .25) Increase in Investment of $5 $ 5.00 $ 3.75 $ 1.25 Second Round 3.75 2.81 .94 Third Round 2.81 2.11 .70 Fourth Round 2.11 1.58 .53 Fifth Round 1.58 1.19 .39 All Other Rounds 4.75 3.56 1.19 $20.00 $15.00 $ 5.00 Total THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT Multiplier Effect and the Marginal Propensities Inverse relationship between: Multiplier & MPS Multiplier Change in GDP = 1 1 or 1 - MPC MPS = Multiplier x initial change in spending THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT MPC and the Multiplier MPC Multiplier .9 10 .8 5 .75 4 .67 .5 3 2 • The size of the MPC and the multiplier are directly related. • The significance of the multiplier is that a small change in investment plans or consumption-saving plans can trigger a much larger change in the equilibrium level of GDP. • The simple multiplier given above can be generalized to include other “leakages” from the spending flow besides savings. For example, the actual multiplier is derived by including taxes and imports as well as savings in the equation. In other words, the denominator is the fraction of a change in income not spent on domestic output.