Ppt - Berkeley Law

advertisement

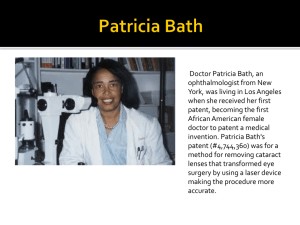

Chapter 5 • • • • • • • • • § 102. CONDITIONS FOR PATENTABILITY; NOVELTY AND LOSS OF RIGHT TO PATENT A person shall be entitled to a patent unless — N (a) the invention was known or used by others in this country, or patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country, before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent, or SB (b) the invention was patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country or in public use or on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States, or SB (c) he has abandoned the invention, or SB (d) the invention was first patented or caused to be patented, or was the subject of an inventor’s certificate, by the applicant or his legal representatives or assigns in a foreign country prior to the date of the application for patent in this country on an application for patent or inventor’s certificate filed more than twelve months before the filing of the application in the United States, or N (e) the invention was described in – (1) an application for patent, published under section 122(b), by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent or (2) a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent, except that an international application filed under the treaty defined in section 351(a) shall have the effects for the purposes of this subsection of an application filed in the United States only if the international application designated the United States and was published under Article 21(2) of such treaty in the English language; or D (f) he did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented, or N (g) (1) during the course of an interference conducted under section 135 or section 291, another inventor involved therein establishes, to the extent permitted in section 104, that before such person’s invention thereof the invention was made by such other inventor and not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed, or (2) before such person’s invention thereof, the invention was made in this country by another inventor who had not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed it. In determining priority of invention under this subsection, there shall be considered not only the respective dates of conception and reduction to practice of the invention, but also the reasonable diligence of one who was first to conceive and last to reduce to practice, from a time prior to conception by the other. • • § 102. CONDITIONS FOR PATENTABILITY; NOVELTY AND LOSS OF RIGHT TO PATENT A person shall be entitled to a patent unless — • N (a) the invention was known or used by others in this country, or patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country, before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent, or … N (e) the invention was described in – (1) an application for patent, published under section 122(b), by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent or (2) a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent, except that an international application filed under the treaty defined in section 351(a) shall have the effects for the purposes of this subsection of an application filed in the United States only if the international application designated the United States and was published under Article 21(2) of such treaty in the English language; or • • • D • N (g) (1) during the course of an interference conducted under section 135 or section 291, another inventor involved therein establishes, to the extent permitted in section 104, that before such person’s invention thereof the invention was made by such other inventor and not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed, or (2) before such person’s invention thereof, the invention was made in this country by another inventor who had not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed it. In determining priority of invention under this subsection, there shall be considered not only the respective dates of conception and reduction to practice of the invention, but also the reasonable diligence of one who was first to conceive and last to reduce to practice, from a time prior to conception by the other. (f) he did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented, or Novelty Test Claims of the Alleged Invention Prior Art Physical Things Articles in Printed Publications Old Patents [A] mechanical fastening system for forming side closures . . . comprising a closure member . . . comprising a first mechanical fastening means for forming a closure, said first mechanical fastening means comprising a first fastening element; a landing member . . . comprising a second mechanical fastening means for forming a closure with said first mechanical fastening means, said second mechanical fastening means comprising a second fastening element mechanically engageable with said first element; and disposal means for allowing the absorbent article to be secured in a disposal configuration after use, said disposal means comprising a third mechanical fastening means for securing the absorbent article in the disposal configuration, said third mechanical fastening means comprising a third fastening element mechanically engageable with said first fastening element . . . . Robertson • Claim Language: • [A] mechanical fastening system for forming side closures . . . comprising – a closure member [e.g. the whole structure of tape or velcro tabs] . . . comprising a first mechanical fastening means [the tape or tabs] for forming a closure, said first mechanical fastening means comprising a first fastening element [the sticky part of the tab]; – a landing member [the part of the diaper front to which the closure member will attach] . . . comprising a second mechanical fastening means for forming a closure with said first mechanical fastening means, said second mechanical fastening means comprising a second fastening element mechanically engageable with said first element [part that attaches to the tab]; and – disposal means for allowing the absorbent article to be secured in a disposal configuration after use, said disposal means comprising a third mechanical fastening means for securing the absorbent article in the disposal configuration, said third mechanical fastening means comprising a third fastening element mechanically engageable with said first fastening element . . . . Robertson • Claim Language: • [A] mechanical fastening system for forming side closures . . . comprising – a closure member [e.g. the whole structure of tape or velcro tabs] . . . comprising a first fastening element [the sticky part of the tab]; – a landing member [the part of the diaper front to which the closure member will attach] . . . comprising a second fastening element mechanically engageable with said first element [part that attaches to the tab]; and – disposal means … comprising a third fastening element mechanically engageable with said first fastening element . . . . Robertson: One Embodiment of the Applicant’s Diaper 60: Closure Member 62: 1st Fastening Means 868: 3rd Fastening Means Note that most embodiments will have two closure members, one for each side. Robertson: Another Embodiment of the Applicant’s Diaper 60: Closure Member 62: 1st Fastening Means 106: 3rd Fastening Means Third fastening means is on the back of the first fastening means. Robertson: Prior Art Wilson Diaper Robertson • Key question is whether the Wilson diaper teaches a “third fastening element” that attaches to the “first fastening element.” • That question cannot be answered simply by comparing the claim language in Wilson’s patent to the claim language in Robertson’s application. Different language could describe the same thing. • Instead, the correct comparison is between Robertson’s language and all of Wilson’s disclosed embodiments. • Anticipation-Infringement Symmetry: The question is whether the Wilson diaper would fall within Robertson’s claim. This is the analysis that would be used in infringement litigation except that, because the Wilson diaper is prior art, a finding that it falls within Robertson’s claim will result in the invalidation of Robertson’s claim. • Here, the whole question boils down to whether one portion of the Wilson diaper can serve as both a first fastening element and as a third fastening element. Robertson • PTO Board: – the Board ruled that one of the fastening means for attaching the diaper to the wearer also could operate as a third fastening means to close the diaper for disposal and that Wilson therefore inherently contained all the elements of claim 76. • Majority: – the Board failed to recognize that the third mechanical fastening means in claim 76, used to secure the diaper for disposal, was separate from and independent of the two other mechanical means used to attach the diaper to the person. Robertson • Judge Rader: – The specification explicitly teaches that the first and third fastening elements can be the same so long as they are complementary, as they are in Wilson. Accordingly, I agree with the Board that Wilson teaches the claimed “third fastening element.” • Patent Specification (now issued as # 6,736,804) – the disposal means 68 may be either a discrete separate element joined to the diaper 20 or a unitary element that is a single piece of material that is neither divided nor discontinuous with an element of the diaper 20 such as the topsheet 26, the backsheet 28, or one of the first fastening elements 62. (For example, one of the first fastening elements may comprise a disposal means if the fastening material is an identical complementary element since the first fastening element of one tape tab may be secured to the first fastening element of the other tape tab.) Robertson • Note that the disagreement between the majority and Judge Rader concerns not what Wilson discloses but what Robertson is claiming. • Is this a victory for Robertson? • Robertson’s claims have now been definitively interpreted as NOT covering a diaper where the first fastening means serve a dual purpose --- to close the diaper while it is being worn and to close the diaper when it is being disposed. • Robertson’s claims issued in May, 2004. • Bifurcated Invalidity Inquiry: Always divide analysis into 1) anticipation; and 2) obviousness. Don’t mix the two!!! Schreiber (Popcorn Top) Schreiber (Popcorn Top) • [T]he examiner was justified in concluding that the opening of a conically shaped top as disclosed by [the Swiss patent] is inherently of a size sufficient to “allow[] several kernels of popped popcorn to pass through at the same time” and that the taper of [the Swiss patent’s] conically shaped top is inherently of such a shape “as to by itself jam up the popped popcorn before the end of the cone and permit the dispensing of only a few kernels at a shake of a package when the top is mounted on the container.” Seaborg • I claim: • 1. Element 95. [Americium.] • The problem: Prior to Seaborg’s work, Fermi had produced element 95 in Fermi’s nuclear reactor (which was located on the University of Chicago’s campus!). • Fermi produced element 95 but didn’t know it. • It is also nearly impossible to find the element 95 because it is mixed in with tons of nuclear waste. Seaborg • The court begins with Hand’s statement: – No doctrine of the patent law is better established than that a prior patent or other publication to be an anticipation must bear within its four corners adequate directions for the practice of the patent invalidated. • The court then reasons that: – the claimed product, if it was produced in the Fermi process, was produced in such minuscule amounts and under such conditions that its presence was undetectable. • It also agrees with Seaborg’s argument that: – The possibility that although a minute amount of americium may have been produced in the Fermi reactor, it was not identified (nor could it have been identified) would preclude the application of the Fermi patent as a reference to anticipate the present invention. Anticipation Analysis • Two possible views: – 1) Anticipation requires that the prior art have appreciated that it was creating the invention. – 2) Anticipation does not require appreciation. If the claims would cover (and therefore enjoin) an activity that was previously practiced, then the claim cannot be allowed because the claim would detract from the public domain and patents can’t do that. • Though opinions contain much language to support theory 1, recent cases make clear that theory 2 is more sound. • To understand why theory 2 is sound, ask this question: Should Seaborg now be able to use his claim to “Element 95” to enjoin Fermi-style nuclear reactors? These reactors “make” element 95. Yet if Seaborg get the right to enjoin the reactors, then the patent system has allowed an inventor to gain rights over something in the prior art – an impossibility! Hafner • 1959: Klaus Hafner files German patent applications on new chemicals; no use is described. • 1960: He files in the US; no use is disclosed. • 1961: Hafner’s applications are published in Germany, and other publication describes the chemicals. • 1964: Hafner refiles in the US after the PTO rejects his first application for failing to satisfy section 112 because no use is disclosed for the chemicals. • PTO now rejects Hafner on the basis of, among other things, his own 1961 publication of his patent specification. The 1961 publication enables for purpose of anticipation even though it does not enable for purposes of 112. • Key difference is that enablement for anticipation does NOT require an known use; section 112 does. • This case is consistent with theory (2). Anticipation prevents any “backsliding” for the public domain. Prior art cannot be patented even if the prior art does not yet have a use! Titanium Metals • 1970: Short Russian article is published. – It is titled “Investigation and Mechanical Properties of Ti-Mo-Ni Alloys. – No use is disclosed. – Alloys that fall within Titanium Metals’ claims are revealed by two dots on published graphs. • 1974: Titanium Metals’ employees file an application. • Russian article constitutes prior art either under 102(a) (probably) or 102(b) (for sure). • The only question is whether the article anticipates the claims. Titanium Metals: Article’s Figure 1 Titanium Metals: Article’s Figure 1 Note two points: 1) The caption for Figure 1 says that chart (c) plots Mo:Ni ratios of 1:3. 2) Chart (c) shows one point where the total percentage of Mo + Ni = about 1%. Since Mo:Ni are mixed in a 1:3 ratio, there must be .25% Mo and .75% Ni in this alloy. Titanium Metals: Article’s Figure 2 Note two points: 1) The caption for Figure 2 says that charts above show alloys from Series III. If that corresponds to alloy (c) (the facts aren’t clear), the Series III will have Mo:Ni ratios of 1:3. 2) Chart on the bottom right side (the editor’s parenthetical in the book might be wrong) shows one point where the total percentage of Mo + Ni = about 1%. Since Mo:Ni are mixed in a 1:3 ratio, there must be .25% Mo and .75% Ni in this alloy. Titanium Metals • Q: Why does the alloy made by the Russians invalidate the claims? • A: The claims cover any Ti alloy containing – Mo (.2% -- .4%): Russian alloy has .25% – Ni (about .6% to .9%): Russian alloy has .75% – Iron (0 - .2%): Russian alloy has 0% Titanium Metals • Q: Why is there no enablement problem here? How can a “dot” be enabling? • A: The court finds: Appellee’s expert, Dr. Williams, testified on cross examination that given the alloy information in the Russian article, he would know how to prepare the alloys “by at least three techniques.” Enablement is not a problem in this case. • Q: Why does the court hold the whole claim to be invalid when only one combination within the many possible combinations is disclosed in the Russian article? • A: If the claim covers prior art, it is not valid. It is the applicant’s job to draft a new claim to exclude the prior art. Broccoli Sprouts Patent Case p.388 • John Hopkins researchers discover that eating cruciferous sprouts prevents cancer. • Q: Why can’t they patent eating sprouts? • A: Federal Circuit has now held: – "Inherency is not necessarily coterminous with the knowledge of those of ordinary skill in the art. Artisans of ordinary skill may not recognize the inherent characteristics or functioning of the prior art.“ – But the [cancer-fighting] potential of sprouts necessarily have existed as long as sprouts themselves, which is certainly more than one year before the date of application at issue here. See, e.g., Karen Cross Whyte, The Complete Sprouting Cookbook 4 (1973) (noting that in "2939 B.C., the Emperor of China recorded the use of health giving sprouts"). … It matters not that those of ordinary skill heretofore may not have recognized these inherent characteristics of the sprouts. Broccoli Sprouts Patent Case p.388 • Holding is consistent with the “no backsliding” principle. People can’t be enjoined from eating sprouts! • Q: How then does John Hopkins get rewarded for discovering this valuable new information? • A: It’s not clear. Not all information is necessarily patentable. Perhaps John Hopkins can apply for a business method patent for markets sprouts as a cancer fighting agent. The problem is that people can still learn that sprouts fight cancer and then buy generic sprouts from firms not licensed by Hopkins. • Note this sort of ruling decreases the incentives to look for new properties of existing substances. References under 102(a) • Statute says that applicant is not entitled to a patent if: a) the invention was – known or used by others in this country, [domestic] – or patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country, [global inquiry] before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent, or National Tractor Pullers v. Watkins • 1963-64: Huls, Harms and Sage allegedly draw the invention at issue on the back of a tablecloth in Huls’ mother’s kitchen. • Sometime later: Watkins invents and patents. • 1977: Huls tries to recreate tablecloth drawing from memory. • The court holds that – Prior knowledge as set forth in 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) must be prior public knowledge, that is knowledge which is reasonably accessible to the public. • Why? The statute says only that it must be known by “others.” Rosaire v. Baroid Sales • 1935 to early 1936: Gulf Oil uses the method at issue. Gulf Oil later stops using the method. • Later in 1936: Horvitz conceives of the method. He later patents it and assigns the patent to Rosaire. • Gulf Oil Corporation employees had used the prospecting method "in the field under ordinary conditions without any deliberate attempt at concealment or effort to exclude the public and without any instructions of secrecy to the employees performing the work." Rosaire v. Baroid Sales • The Fifth Circuit held that where "work was done openly and in the ordinary course of the activities of the employer," the work qualifies as a prior use for purposes of § 102(a) even though Gulf had discontinued use of the method and had not made any "affirmative act to bring the work to the attention of the public at large." • Why doesn’t this court follow National Tractor Pullers? Was Gulf’s work “reasonably accessible to the public”? Jockmus v. Leviton • 1908: Catalogue is circulated in France. At least 50 copies. • Later: Patentee invents. • Q: Why is the catalogue a printed publication? • A: The court holds that a publication must have “enough currency to make the work part of the possession of the art.” – Note: A single copy in a library may be enough. Later cases hold that a single copy is enough if the copy is indexed by subject (In re Hall), not if indexed by author and kept in a shoebox (In re Cronyn). Klopfenstein • 1998: Display of slides at conference meeting. Slides were displayed on posters. People were free to copy the slides. • 2000: Application is filed. 1998 display of slides could qualify under 102(b). • Even ephemeral publications can be publications. • Court considers: 1) the lack of confidentiality explicit or implicit, and 2) the simplicity of the invention. “Patented” References • This is not an important category of references. Why? • What would be a hypothetical in which a reference would qualify as patented but not as published? Publication Problem • 1/1/04: I send the final version of my article on “A New Method of Chip Production” to the journal “Engineering Today” which is published by GWU. • 1/15/04: I place the article on my personal web page. • 2/1/04: Copies of the journal issue containing my article roll off the presses and are shipped via third-class mail. • 2/2/04: One copy of the issue begins to circulate in GWU’s engineering dept. • 2/3/04: One copy is put in the GWU Engineering Library (indexed as vol. 4 issue 2 of “Engineering Today”). • 2/5/04: At least 20 libraries receive their copies; • 2/6/04: The 20 libraries index the journal as GWU did. • 2/7/04: 30 individual subscribers receive the journal. • Q: When does the article enter the prior art? “Defensive” Publications • Even parties who do not want to patent their developments need to know the publication rules because they may want to prevent other parties from obtaining patents on those developments. • Patent lawyers thus may sometimes advise their clients to make a “defensive” publication – a publication that will prevent others from seeking patent rights on a development that the client has made but does not want to patent. • Some firms specialize in making such publications quickly and at low cost. “Defensive” Publications: Advertisement for a firm specializes in defensive publication “Defensive” Publications: Advertisement for a firm specializing in defensive publication Prior Art Searching • Many other firms specialize in searching the prior art. These searches help attorneys: – To advise their clients whether a development is patentable in light of the prior art; and – To draft patent claims that are patentable in light of the prior art. • A prior art search is not, however, a prerequisite for filing a patent application. Many inventors do not conduct a prior art search but instead simply rely on the PTO’s search. That practice can be dangerous because, if the PTO does not find some relevant art, those references could invalidate claims in infringement litigation. • Cost of search is approx. $275+ (see next slide). Prior Art Searching: Advertisement for a prior art search firm Alexander Milburn Co. v. Davis-Bournonville Co. • Jan. 31, 1911: Clifford files an application disclosing but not claiming an improvement in welding and cutting apparatus. • March 4, 1911: Whitford files an application claiming the improvement disclosed in Clifford's application. Whitford’s filing date was his date of invention because, as the Court noted, “[t]here was no evidence carrying Whitford’s invention further back [of his filing date].” • Feb. 6, 1912: Clifford's patent is issued. • June 4, 1912: Whitford’s patent is issued. • Later: Whitford’s assignee sues Milburn Co. Alexander Milburn Co. v. Davis-Bournonville Co. • Q: Why does Holmes invalidate this patent? • A: He relies on the statutory command that the patent applicant must be “the original and first inventor or discoverer … of the thing patented.” Whitford was not the inventor because Clifford had disclosed the invention more than a month before Whitford’s invention. • Q: Does a patent application always become part of the prior art under Holmes’ ruling? • A: No! It will only become part of the prior art if the patent actually issues. The Patent Office did not search abandoned application (which were then secret) and Holmes does not disturb this practice. 102(e): Disclosures in U.S. Applications • Codifies the Milburn rule, except that 1999 amendments make applications part of the prior art as of their filing date if they are published under the PTO’s 18-month publication rule (not just if they are issued). • Q: How is a 102(e) different from an interference? • A: Interferences occur when both inventors claim the subject matter. A 102(e) objection can occur only where the earlier filer disclosed the subject matter that is being claimed by a later filer. • Q: How is 102(e) different from publication prior art under 102(a)? • A: Publications enter the prior art only upon publication – i.e., when the public receives the information. The delays of the publisher do count against the publication. By contrast, patent filings become part of the prior art as of the date of filing if they ultimately become public. 102(e): Disclosures in U.S. Applications • Q: Do any international filings qualify for as prior art under 102(e)? • A: Generally no, though there is one exception. – 1. Disclosures in a foreign application for a foreign patent do not get 102(e) treatment. They become part of the prior art only when they are published. – 2. If an applicant files overseas first and then files at the US PTO within one year, then the US application is entitled to be treated as if it had been filed in US at the time of the foreign filing (see 35 USC 119) except that the 102(e) rule applies from the date of the actual US filing (see In re Hilmer). – 3. Exception: If the applicant files a PCT application anywhere, it does qualify for 102(e) treatment if it “designates” the US as a country wherein patent rights are sought and it is published in the English language. 102(e): Disclosures in U.S. Applications • Q: Why have this rule? • A: Here are two reasons: – 1. Patent applications provide a good storehouse of knowledge that the PTO can easily search. If something is disclosed but not claimed in an application, that applicant must have thought it not new or nonobvious, or not worth the trouble to claim. Very few high-value inventions are likely to fall into this category. – 2. If the information is disclosed in the applicant’s specification, then it is probably necessary for that applicant to make or use her invention (or necessary for using it in the best mode). Granting a patent on that information to a later applicant is not fair to the first applicant because it will cut down on the value of the first applicant’s patent rights and quite likely create blocking patents against the first applicant’s technology. 102(e): Disclosures in U.S. Applications • Jan. 1, 2004: I file an application claiming A but also disclosing B. • June 1, 2004: Smith files an application claiming B. • Q: Can Smith obtain a patent on B? • A: Yes, maybe. If my application never issues or is never published, then Smith can patent B. • Q: Will Smith and I get into an interference? • A: Not unless I amend my claims to seek a patent on B too. • Q: What does the PTO do with Smith’s application? • A: It cannot reject it until my application has been issued or published. Another Problem • 1/1/04: Jones files a U.S. application. • 7/1/05: Jones’ application is published by the PTO; it claims A but fully discloses B too. • 12/1/05: Jones’ patent issues. As issued, it claims A and B too. • 5/1/06: I file an application seeking a US patent on B. • 12/1/06: US courts invalidate Jones’ patent for failure to comply with the Best Mode Requirement. • Q: Can I get a patent on B? • A: Maybe, if I can prove an invention date prior to 1/1/04. (Jones’ work may also qualify as prior art under 102(g), and that provision may push the reference date of his work earlier.) Another Problem • 1/1/04: Jones files an application in India. • 7/1/05: Jones’ application is published by the Indian patent office; it claims A but fully discloses B too. • 12/1/05: Jones’ Indian patent issues. As issued, it claims A and B too. • 5/1/06: I file an application in the U.S. seeking a patent on B. • 12/1/06: Indian courts invalidate Jones’ patent. Jones never seeks US patent rights. • Q: Can I get a US patent on B? • A: Maybe, if I can prove an invention date prior to 7/1/05. (Jones’ work cannot qualify as prior art under 102(g)(2) if it did not occur in US.) 102(f): Don’t Copy!!! • This rule is timeless and global: If the alleged inventor copied from someone else, then the patent is invalid. • Agawam Co. v. Jordan, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 583 (1869). Suggestions can defeat an issued patent only if they “embraced the plan of the improvement” and “would have enabled an ordinary mechanic, without the exercise of any ingenuity and special skill on his part, to construct and put the improvement in successful operation. • Corroboration Rule: Oral testimony alone cannot defeat an issued patent; there must be some corroboration, though a rule of reason is applied in determining the sufficiency of corroboration. Also the evidence must be “clear and convincing” to invalid. Christie v. Seybold: Timeline • October 1885: Seybold conceives of a new device to be used in a power press for bookbinding. • Summer 1886: Christie allegedly conceives of his own power press, which is similar to Seybold’s invention. • July 12, 1888: Christie completes the production of his first power press. • April 1889: Seybold’s first power press is made. • June 6, 1889: Seybold files. • June 7, 1889: Christie files. Christie v. Seybold: Simplified Timeline • • • • • • October 1885: Seybold conceives. Summer 1886: Christie conceives. July 12, 1888: Christie RTP. April 1889: Seybold RTP. June 6, 1889: Seybold files. June 7, 1889: Christie files. Christie v. Seybold Christie Conception: Summer 1886 Conception: 10/1885 Seybold Reduction to practice: 7/12/1886 Filed: 6/7/1889 R to P: Filed: 4/1889 6/6/1889 Christie v. Seybold: Legal Standard • P. 451-452: The rule of priority is “that the man who first reduces an invention to practice is prima facie the first and true inventor, but that the man who first conceives . . . [an invention] may date his patentable invention back to the time of its conception if he connects the conception with its reduction to practice by reasonable diligence on his part, so that they are substantially one continuous act.” Christie v. Seybold: The role of diligence • “The burden is on the second reducer to practice to show the prior conception, and to establish the connection between that conception and his reduction to practice by proof of due diligence . . .” – p. 452 • While diligence can be used to push the date of invention all the way back to the time of conception, the second to RTP need only prove diligence before the other inventor’s conception in order to win the priority fight. Christie v. Seybold Christie Conception Reduction to practice Conception ONLY Seybold’s diligence matters because Seybold is the first to conceive but last to reduce to practice. R to P Diligence Christie v. Seybold Christie Conception C Reduction to practice R to P For Seybold to have won, he would have had to prove diligence from JUST PRIOR to Christie’s conception. Christie v. Seybold • Q: What’s the basic rule of priority? • A: Generally, the first to reduce to practice wins the race, with three caveats. – 1. Filing counts as a reduction to practice. – 2. The first to conceive and last to reduce to practice may claim an earlier date as the date of invention if unbroken diligent efforts were begun prior to the other party’s conception. With unbroken diligence, the date of conception could be the earliest invention date. – 3. Abandoned efforts are not counted. • Q: What are excuses for inactivity? • A: “The sickness of the inventor, his poverty, and his engagement in other inventions of a similar kind are all circumstances which may affect the question of reasonable diligence.” CHRISTIE v. SEYBOLD • Q: Why does Seybold lose here? • A: His poverty excuse was found wanting. He still could have completed his invention in another shop. • Q: Why should poverty generally be considered a bad excuse? • A: The cost of filing an application is minimal, and filing is a “constructive reduction to practice.” Note that an applicant can also file a “provisional application” and delay prosecution for 1 year. The provision application must, however, still comply with all of Section 112 except for the claiming requirements. • Q: Tie on RTP? • A: First to conceive wins. • Q: Tie on filing on no other proof? • A: No one gets a patent !!! Peeler v. Miller • March 14,1966: Miller reduces to practice an improved hydraulic fluid to his employer. • April, 1966, Miller discloses the invention to his employer the Monsanto Company. • January 4, 1968: Peeler files a patent application on a fluid identical to Miller’s discovery. • October 1968: Two and a half years after Miller’s discovery, the Monsanto Company restarts work to acquire patents on this and other company discoveries. • April 27, 1970: Miller files a patent application. • July 6, 1971: The PTO issues a patent to Peeler. Peeler v. Miller Peeler et al. rely only on filing date: 1.4.1968 March, 1966: Miller conceives and, on March 14th, RTP. April 27, 1970: Miller files (finally!!). § 102(g) “Abandoned, Suppressed, or Concealed”: Occurs After RTP! R to P March, 1966: Miller RTP. Filing Date April 27, 1970: Miller files (finally!!). Excessive delay here is considered “concealment” for purposes of 102(g) Peeler points • “Counts” are basically claims. – This is just special interference lingo. • The court rejects the argument that Miller’s March, 1966 results were just an “abandoned experiment.” • An abandoned experiment would mean that there was no RTP. It would mean that the experiment was not enabling. See also Rosaire, where the court refused to find that a limited use of a process was merely an abandoned experiment. Peeler points cont’d • P 458: “Which of the rival inventors has the greater right to a patent?” – Classic Judge Rich approach to invention priority issue. – See also Paulik, p. 462: Judge Rich’s concurring opinion states: • It must be recognized that we are deciding a priority issue: which party is to be regarded as the “first” inventor in law, regardless of fact. The award … should be to the one most deserving from a policy standpoint. • P.459: “In our opinion, a four year delay from [RTP to filing] is, prima facie, unreasonably long in an interference with a party who filed first.” Compare to Diligence under §102(g): Diligence is relevant before RTP. Christie Conception Reduction to practice Conception ONLY Seybold’s diligence matters R to P Interferences – some fine points • Administrative Trial under §135 before the USPTO Bd Pat Int & App. An appeal lies to Federal Circuit 35 USC § 141 … • OR a party can sue in district court under § 146, with the appeal from the trial going ultimately to the Federal Circuit. – This course is rare because it increases litigation costs without changing the ultimate decisionmaker (Fed. Cir.). Paulik v. Rizkalla Rizkalla files: March 10, 1975 Nov., 1970 & April 1971: Paulik RTP. Feb, 1975: Paulik’s attorney begins efforts to file. June 30, 1975: Paulik files (finally!!). Paulik v. Rizkalla Ignore the abandoned, suppressed or concealed work from 1970/71. Rizkalla files: March 10, 1975 Nov., 1970 & April 1971: Paulik RTP. Feb, 1975: Paulik’s attorney begins efforts to file. June 30, 1975: Paulik files (finally!!). Paulik wins because his attorney is diligent during this period. Paulik v. Rizkalla Paulik can then claim to be first to conceive and last to RTP. If his attorney was diligent in RTP (constructively), then his date of invention can go back before March 10, 1975. Nov., 1970 & April 1971: Paulik RTP. (Re)conception Rizkalla files: March 10, 1975 Feb, 1975: Paulik’s attorney begins efforts to file. June 30, 1975: RTP Paulik files (finally!!). Diligence Dow Chemical v. Astro-Valcour • April 19, 1968: Japanese Styrene Paper Company (JSP) receives a patent for a process to produce foam using non-CFC blowing agents (the “Miyamoto patent”). • August 22, 1984: After purchasing a license to the Miyamoto patent, Astro-Valcour, Inc. (AVI) makes foam with isobutane using the Miyamoto process. • August 1984 – Sept. 1986: AVI builds facility to produce the invention. • August 24-28,1984: Dr. Chung Park with the Dow Chemical Company conceives a similar process and product. • Sept. 1984: Park reduces to practice. • Dec. 1985: Park files. • September 1986: AVI begins commercial production of its new foam. Dow Chemical v. Astro-Valcour Park (Dow) conceives: Park RTP: Sept. 1984 Park files: Dec. 1985 Aug. 24-28, 1984 1968: Japanese patent Aug. 22, 1984: AVI blows foam: RTP. Sept. 1986: AVI begins commercial production. Does the 2+ year delay after RTP constitute concealment? Dow Chemical v. Astro-Valcour • AVI is an inventor of the process and product even if AVI’s employees didn’t think they were inventive. – No requirement in the statute that an inventor must recognize the inventive nature of the creation. – Policy: Only relatively trivial inventions are likely to have this problem. • AVI did not abandon provided that, during the 2+ years between RTP and disclosure, it was taking “reasonable efforts to bring the invention to market.” – Compare 4 year delay in Peeler. Note that in Peeler reasonable efforts were not being made to bring that invention to the public during the delay. • 102(g)(2) backdates prior art to time before publicity; it is only a domestic inquiry. 102(g) Prior Invention Art • Differences between 102(g)(1) interference prior art and prior art from other novelty sections (a) & (e): – Art must be claimed in a US application to qualify under 102(g)(1)! • Differences between 102(g)(2) non-interference prior art and prior art from other novelty sections (a) & (e): – Requires prior invention --- must be a RTP! Cf. (a) and (e). – Domestic inquiry only, unlike patented and printed publication art from 102(a). – Note: 102(a) art that is “used in this country by others” (Rosaire–type prior art) might always qualify under 102(g)(2) also. Since (g)(2) art may allow early reference date, (g)(2) might “swallow” Rosaire–type prior art. Trade Secrets: Not Prior Art! • They don’t qualify under 102(a) because they are not public. • They don’t qualify under 102(g) because, although there is prior invention, the invention is “concealed.” Gould v. Schawlow • This case shows that conception requires conception in detail. The inventor must have known enough to instruct a person skilled in the art how to practice the invention. • Schawlow filed July 30, 1958. (Constructive RTP.) • Gould filed April 6, 1959. (Constructive RTP.) • Under such circumstances it is, of course, well established interference law that the junior party, here Gould, must prove by a preponderance of the evidence (1) conception of the invention prior to July 30, 1958, and (2) reasonable diligence in reducing it to practice commencing from a time just prior to July 30, 1958, to his filing date of April 6, 1959. • Gould’s notes give a good theoretical description of the laser but do not specify that the side walls of laser cavity must be “transparent to the pumping energy” AND “transparent to or absorptive of other energy radiated thereat.” Gould v. Schawlow Gould v. Schawlow • Schawlow’s claim: • 1. A maser generator comprising a chamber [marked 14 in Figure 5-10] having end reflective parallel members [16 & 17] and side members [15], a negative temperature medium disposed within said chamber, and means [20] arranged about said chamber for pumping said medium, said side members being transparent to the pumping energy and transparent to or absorptive of other energy radiated thereat. Gould v. Schawlow • Gould’s notes: Some rough calculations on the feasibility of a LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation[.] [C]onceive a tube terminated by optically flat, partially reflecting parallel mirrors. The mirrors might be silvered or multilayer interference reflectors. The latter are almost lossless and may have high reflectance depending on the number of layers. A practical achievement is 98% in the visible for a 7-layer reflector. . . . Consider a plane standing wave in the tube. There is the effect of a closed cavity; since the wavelength is small the diffraction and hence the lateral loss is negligible. If the tube contains an excess of atoms in a higher electronic state, a plane travelling wave may grow by inducing transitions in the atoms, which must add energy to the wave . . . . There are several possibilities for excitation: A. Optical excitation from an external discharge. . . . Gould v. Schawlow • Q: Do Gould’s notes indicate that the laser’s side walls must be “transparent to the pumping energy” of the laser? • A: Possibly. He does say that one of the “possibilities for excitation” include “[o]ptical excitation from an external discharge.” The energy from the external optical excitation would have to enter to the laser chamber somehow. The chamber has mirrors on its ends, so the side walls seem to be the only possibility. • The harder point to find in the notes is the requirement that the side walls be “transparent to or absorptive of other energy radiated thereat.” Gould v. Schawlow (con’t) • Gould tried to fill in the gaps in his notes with expert testimony to the effect that a person skilled in the art would have understood the notes to include the elements that were not explicitly mentioned. • One problem is that the “art” in 1957 was very primitive – a laser hadn’t yet been built. Thus, the court is skeptical of Gould’s experts; it states: “we are unable to determine how much, if any, [the experts’] views might be affected by knowledge of the requisite structure of a laser device acquired during the intervening years [between 1957 and 1963, when the experts were testifying].” • Ultimately, the court holds that “evidence of conception … must must show a complete conception, free from ambiguity or doubt.” Gould’s notes failed this standard because the notes were “susceptible of numerous interpretations, each ostensibly plausible.” Diligence • Does not break diligence: – (1) poverty and illness (generally a valid excuse for lapses in diligence if the circumstance really do prevent work on the invention); – (2) regular employment; and – (3) overworked patent attorney (excuse for delay in achieving constructive RTP). • Does constitute a break in diligence: – (1) Attempts by a university research to get outside funding (at least where sufficient funding is available inside the university), see Griffith v. Kanamaru; – (2) Attempts to get commercial orders; – (3) doubts about value or feasibility of invention; and – (4) work on other unrelated inventions. RTP • DSL Dynamic Sciences: A RTP need not be a commercial or marketable product. It must only “actually work[] for its intended purpose.” “[T]ests performed outside the intended environment can be sufficient to show [RTP] if the testing conditions are sufficiently similar to those of the intended environment.” • Estee Lauder v. L’Oreal: RTP requires knowledge by the inventors that the invention works for its intended purpose. – “[I]n addition to preparing a composition, an inventor must establish that he ‘knew it would work,’ to reduce the invention to practice. This suggests that a reduction to practice does not occur until an inventor, or perhaps his agent, knows that the invention will work for its intended purpose.” Id. at 593. – Note the connection here with the “accidental anticipation” doctrine of Seaborg and Tilghman v. Proctor: Just as unappreciated phenomena are not considered prior art, so too they are not considered inventions for establishing priority. Multiple Interferences • If the statutory language is read to preclude any consideration of diligence here (why should it be?), then only the dates of conception and RTP matter. Since ordinarily the first to RTP wins, perhaps Inventor C should win. • But … there are many other possible solutions. Note that the statutory language doesn’t really seem to contemplate this problem. In re Moore: Rule 131 Practice • Before Dec. 1963: Moore prepares a new compound. He does not yet know a use for it. • Dec. 1963: A British chemistry journal publishes an article describing the new chemical compound without describing a use for it. • Nov. 24, 1964: Moore files a US patent application claiming the compound. Note: He must now have a use for it. • Q: Can Moore “antedate” the British journal by proving he invented the compound first? • A: Yes. In effect, the court allows a Rule 131 affidavit to prove a date of “partial” invention. In re Moore: Rule 131 Practice • Before Dec. 1963: Moore prepares a new compound. He does not yet know a use for it. • Dec. 1963: An article in a British journal describes the new compound without disclosing a use. • Nov. 24, 1964: Moore files a US patent application claiming the compound. Note: He must now have a use for it. • Q: Can Moore “antedate” the British journal by proving he invented the compound first? • A: Yes. In effect, the court allows a Rule 131 affidavit to prove a date of “partial” invention. This rule applies outside of interferences – i.e., where the alleged prior art reference is NOT another inventor seeking to claim patent rights over the same invention. In re Moore: Rule 131 Practice • The rule in Moore permitting proof of partial invention to antedate a reference applies generally. In Stempel, for example, the inventor was claiming a genus of chemicals and a reference disclosed one species of the genus. Stempel was allowed to antedate that reference by showing that he had discovered that particular species prior to the reference’s date. • Note Rule 131 does not require corroboration, though the affidavit must convince the PTO that the applicant had invented prior to the date of the reference. • Rule 131 practice uses the same standards for determining dates of invention as in interferences: RTP or conception + diligence prior to reference date. International Considerations: Filing Date • Filing date in a foreign country may constitute an effective US filing date for prior purposes only (!!!) pursuant to the Paris Convention as implemented in 35 USC § 119: – An application filed in another Paris Convention country “shall have the same effect as the same application would have if filed in this country on the [foreign filing date], if the application in this country is filed within twelve months from the earliest [foreign filing] date ….” – Priority purposes only. – 12 month window to file after first filing. International Considerations: Proving Date of Invention • Old Rule: All inventive work outside of U.S. is ignored. • New Rule (§ 104): All inventive work inside U.S. and any other WTO country (100+ countries) is treated equally. Work in non-WTO countries is still ignored (excepting special circumstances – e.g., working in an non-WTO country on behalf of the government of a WTO country). International Considerations: Geographic Restrictions on Prior Art • While TRIPs forbids countries from discriminating as to the place of invention for parties seeking patent right, it does not forbids geographic discrimination in defining prior art. Thus, the US still limits some prior art categories based on geography: – 102(a): Prior art inventions “known or used in this country” – 102(g)(2): Prior art inventions “made in this country.” – Cf. 102(e): Applies only to actual US filings. Hilmer • Jan. 24, 1957: Habicht files a patent application in Switzerland disclosing but not claiming certain new chemical compounds. • July 31, 1957: Hilmer files an application for a German patent claiming the compounds disclosed in Habicht’s January 1957 Swiss application. • Jan. 23, 1958: Habicht files his patent application in the United States, which discloses but does not claim the compounds. • July 25, 1958: Hilmer applies for a U.S. patent on his invention. Pursuant to § 119, he relies on his German filing date as his effective U.S. filing date. Hilmer Habicht files in Switz. Filing discloses but PTO wanted to use 119 does not claim to backdate Habicht’s chemicals: disclosure for 102(e) prior art purposes. Jan. 24, 1957 July 31, 1957: Hilmer files in Germany Habicht files in US: Jan. 23, 1958 July 25, 1958: Hilmer files in U.S. Pursuant to § 119, Hilmer can rely on his German filing date as his effective U.S. filing date. Hilmer Habicht files in Switz. Filing discloses but Court holds that 119 can be does not claim used only for priority chemicals: purposes – i.e., if Habicht is Habicht files in US: claiming the chemicals. Jan. 23, 1958 Jan. 24, 1957 July 31, 1957: Hilmer files in Germany July 25, 1958: Hilmer files in U.S. Pursuant to § 119, Hilmer can rely on his German filing date as his effective U.S. filing date.

![Introduction [max 1 pg]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007168054_1-d63441680c3a2b0b41ae7f89ed2aefb8-300x300.png)