02_how_to_make_a_premier_in_the_arts

advertisement

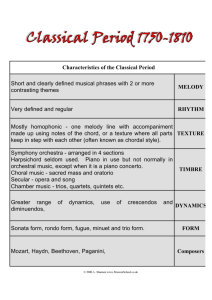

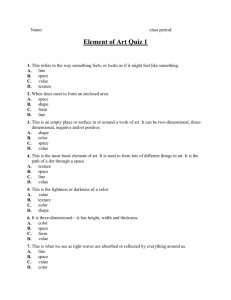

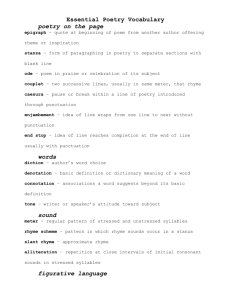

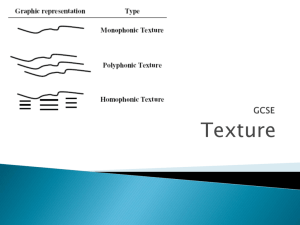

MAKING A PREMIER IN THE ARTS USING PRINCIPLES & ELEMENTS Jump to the Elements Navigation Panel – HUMA1315 – Spring 2011 – J. Walter YOUR PROCESS 1. Find an explicit purpose, motivation, message, excuse, need, or reason to make art. 2. Select your form of art. (painting, play, photograph, poem, piece of music). 3. Plan by making decisions about your use of the principles of art works, specifically addressed through the elements of your art form. Decide which of the elements and principles you will focus on in your work. Select media or aspects of your art which allow you to focus on those elements & principles. 4. Make your art! Pay attention to the process, constantly asking yourself, “how is it going?” in terms of how your execution is following your plan. 5. Evaluate your art by accessing how it happened in relation to your plan, and also in relation to your feelings about the process AND the product – use this evaluation to plan your presentation, reflecting on how the result matches your goals, and how your feelings are affected. Prepare your presentation as a story about your goals versus the result. DOING YOUR MY PREMIER IN THE ARTS PROJECT BEFORE anything else happens, know that you should Pre-Plan to keep notes on your process. This is because you have to make a presentation, your final and ultimate goal. Think of a way to keep notes on your process so that it is easy to put together the presentation of your project.0 1. Set your Goals • What do you want to say? What do you want others to think, or feel? What do YOU feel or think? What is your purpose? 2. Select the Art Form that will help you achieve your goals • Photograph, Painting, Poem, Play, Piece of Music 3. Select the Principles that will help you achieve your goals • Can you express your goals through affecting Emphasis, Balance, Unity, Contrast, Movement, and/or Pattern? You will learn about these principles in this presentation. 4. Select the Elements of your art form to help you manipulate those principles. • The elements for each of the art forms will be addressed in this presentation. 5. Get your materials together, get prepared… then DO IT! 6. When finished making the art, take your notes on the process, consider your own feelings/thoughts about the result (art work), and write the story of your premier! This will help you form an outline for your presentation DOING YOUR PREMIER Your Purposes, Reasons, Message PLAN IT PRESENT IT DO IT The Principles of Art Works The Elements of Your Art Form KEEP NOTES ON THE PROCESS THE ELEMENTS OF THE ARTS - INTRODUCTION You will use the Elements of your specific art form to plan and execute your premier. This presentation will lead you toward those elements. Because each art form or discipline of art has its own characteristics of creation and analysis, the elements of each form are usually unique in comparison to those of another form. The elements of music are not exactly comparable to those of painting, for example. When you choose the form of art you want to work in, you’ll need to learn about the elements of that form, then you’ll be ready to manipulate those elements to affect the Principles of Art Works. This presentation will outline some of the elements of each art form and provide guidelines for how you can apply those elements to the Principles of Art Works. We’ll look at the Principles first (go figure!), because they will guide your application of the elements in your work. THE PRINCIPLES OF ART WORKS Before looking at the elements of each art form, let’s consider the principles that guide their application These Principles of Art Works are choices or areas of focus about the different possibilities you have for arranging, composing, and applying the ELEMENTS of each art form. The principles guide you in your use of an art form’s elements so that you can create works that are artistic, interesting, expressive, emotional, innovative, provocative, and/or powerful. Emphasis Balance Unity Contrast Movement/ Rhythm Pattern/Repetition THE PRINCIPLE OF EMPHASIS Emphasis refers to developing points of interest to pull the viewer's eye, the readers mind, or the listener's ear to important parts of the body of the work. Emphasis is stressing a particular area of focus rather than presenting a maze of details of equal importance. Visually: You can achieve the equivalent of a “black triangle” in all forms of art. For example, a strong melody or strident harmony in music, a stressed image or alarming word in poetry, or a main character or striking scene in the plot of a play. THE PRINCIPLE OF BALANCE Balance is stability in the body of an art work, achieved by creating a feeling of equal weight between the elements of the work. Symmetrical balance is when the artist places “heavy” elements equally on balanced “sides” of an art work. Asymmetrical balance is when a sense of equal weight is achieved with elements of different sizes or types, or with different elements (color, etc). You can balance a long musical melody with two shorter melodies, strong light on one side of a photograph with strong shadows on the other, etc. You can also REJECT balance and symmetry in order to make a statement or send a message. THE PRINCIPLE OF UNITY Unity is achieved when the parts of an art work equal or support the entire work. An art work is unified when it seems to hold together, and when listeners/viewers/readers sense that each part of the art work “fits” with the others. Listen to “unified” music Click this box: Listen to “NON-unified” music Click this box: Note – you can tap your foot to the “regular” tempo, the instruments are unified, the melody is unified. Note – you can’t tap your foot because of the irregular tempo, the instruments are varied, there are multiple melodies. When s/he wants to achieve unity, an artist focuses on making sure there is a clear sense of similarity and consistency in each of the elements used in the art, and also amongst and between all of those elements. NEXT SLIDE THE PRINCIPLE OF CONTRAST The opposites and differences in the art work. Artists exploit contrast to achieve a sense of variety in their work, to affect movement and rhythm, and/or to affect the feelings of their viewers/listeners/readers. You can focus on contrast by altering shapes, changing the tone of the language, adapting a hue and saturation of colors, changing the tempo, using different instruments or characters, changing the highlighting and shading , etc. THE PRINCIPLE OF MOVEMENT/RHYTHM Movement directs the attention of your viewer/reader/listener by adding a sense of action. You can create movement with shapes, words, sounds, and manipulating an art work’s structural elements. Rhythm is the specific type of movement used. It can be focused on rate or pace of motion for the entire art work, or on particular instances of movement in specific places in the art work. Poets create rhythm by repeating words and phrases, as Walt Whitman does in "Song of Myself": I hear the sound I love, the sound of the human voice, I hear all sounds running together, combined, fused, or following, Sounds of the city and sounds out of the city, sounds of the day and night, Talkative young ones to those that like them, the loud laugh of work-people at their meals... Notice the change in rhythm near the end of this excerpt THE PRINCIPLE OF PATTERN/REPETITION An artist can repeat an element of the art work, making it occur over and over again. You can repeat words, themes, sounds, harmonies, actions, colors, shapes, etc. S/he can plan and execute a consistent pattern of repetition for a given element, with breaks between repetitions. Or, s/he can create an inconsistent pattern or repetition, making the element “structural” in various and varying ways. REVIEWING THE PRINCIPLES OF ART WORKS Emphasis Balance Unity Contrast Movement/ Rhythm Pattern/Repetition As you move on to consider the elements of each of the art forms, remember that most artists work from “principles-TOWARD-elements” Artists work to achieve their goals by exploiting these principles – and in order to do that, they adapt and manipulate the elements of their art form. In general, FOR ARTISTS MAKING ART PRINCIPLES ARE PRIMARY! Return to the Home Page THE ELEMENTS NAVIGATION AND DISCLAIMER! This guide does NOT attempt to present anything like a complete or exhaustive list of elements for each of the art forms. Once you have selected a form of art to work in, you should do your own research on that form of art so that you can find, understand, and then use more of that form’s elements, if you so choose. What is presented here is a somewhat arbitrary and ONLY foundational list of elements for each of the forms. However, this listing of basic, partial & limited elements WILL allow you to successfully create a work in one of the forms. CLICK ON THE LINKS IN THE TABLE BELOW TO GO TO THAT SECTION ART FORM FOUNDATIONAL ELEMENTS PRESENTED PHOTOGRAPHS (1)Line (2)Color & Value (3)Space (4)Editing PAINTINGS (1)Line (2)Color & Value (3)Texture (4)Size/Proportion POETRY (1)Meter (2)Simile/Metaphor (3)Rhyme (4)Diction PLAYS (Drama) (1)Action/Plot (2)Character (3)Language/Dialog 4)Scene(ry) MUSIC (1)Melody (2)Tempo & Meter (3)Texture (4) Dynamics PHOTOGRAPHY– THE ELEMENTS Line Color & Value Space Editing LINES IN PHOTOGRAPHY A mark made by a moving point. Directs the eye – horizontal, vertical, diagonal, curvy, zig-zag, etc. Can be either actual, obvious lines or the borders/edges of shapes. Note the use of LINE in these photos. Which of the Principles of Art are affected by the line: Emphasis, Balance, Unity, Contrast, Rhythm, or Pattern? More than one? You can “exploit” the element of LINE in your premier. IF you do so, you should be thinking about the Principle you are affecting. That will give you something to talk about in your presentation! PHOTOGRAPHIC COLOR & HUE & SATURATION You need light to see color. Made of Primary, Secondary, Intermediates. Edit color schemes to enhance appeal or make impact. VALUE Black & White & Grays in between Light to Dark Adds drama & impact to Look for the “value” we can readily see in Black & White when you move to color. PHOTOGRAPHIC VALUE & COLOR (MORE EXAMPLES) Photographic Artists can manipulate Value & Color in various ways: • By carefully choosing what to photograph • By carefully choosing how to photograph it (with extra lights, in daylight, at night, etc.) • By carefully editing the raw image in post-production (another element we’ll discuss) SPACE AND PHOTOGRAPHY The area used or unused in a composition. Positive space = the area the objects/subject takes up. Negative space = the area around, under, through and between. Gives the photo a 3-dimensional feeling. (Depth) This element also involves the Foreground (closest), Middle ground, and Background (farthest). The use of space can be open, crowded, near, far, etc. Space is an element controlled by what you photograph and how you photograph it – it may be more difficult to “edit in” a manipulation of space. EDITING PHOTOGRAPHS Most photo editing software programs allow you to manipulate the basics – levels, values, hues and saturations. You should also be able to crop and resize. These can help you create Balance & Unity in your work. Learn about and use “layers” in your editing program. Imagine stacks of plastic overlays on your photo, each one either transparent or opaque, some having texts, some providing a deepening or darkening of the image – a tool for editing in Emphasis, Contrast, and Movement. Editing software will also allow you to rotate images, invert the colors, etc. Be careful to work on these more creative options using only a copy of your original. In fact, one option – if you have a purpose for doing so – is to present two or more versions of your photo, using the more creative editing options to express an emotion or make a statement. MAKING A PHOTOGRAPH FOR YOUR PREMIER IN THE ARTS! Study and research the elements of photography that have been presented here, then look for others in your own research. Decide how you can focus on the Principles by using the elements. Plan your photo shoot – schedule extra time. Develop your photograph. If you want to explore options, visit a photo store and ask questions. When you have made the art work, work on your presentation. Tell the story of your process (word process it for submission via Campus Cruiser). Prepare how you will show your work. You can project Return to MENU it in the classroom, or mount/frame it for viewing. PAINTING– THE ELEMENTS Line - Color & Value - Texture - Size & Proportion LINES IN PAINTING As in photography, a line is a mark made by a moving point which directs the viewer’s eye and can be horizontal, vertical, diagonal, curvy, zig-zaggy, etc. Occurs as either actual, obvious lines OR the borders/edges of shapes Lines which are vertical/horizontal have a feeling of order and Unity. Diagonals, are more dynamic and suggestive of Movement. COLOR AND VALUE IN PAINTING – PAGE 1 Tone is also called Saturation Color is the result of wavelengths of light reflecting off objects. Objects absorb certain wavelengths and reflect others. The human eye sees the reflected wavelengths as hues, or color: most simply red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet and red. Value is the lightness or darkness of a color, or hue. Even a subtle change in value can define a shape AND SEND A MESSAGE. Learning to see and manipulate the value of a color strengthens an artist’s ability to control shapes and forms to guide the viewer’s eye through the painting. COLOR AND VALUE IN PAINTING – PAGE 2 The top image is a greyscale copy of the “real” color painting. Notice what you can see in the upper righthand corner. The artist has used a soft or light Value/Hue for the yellow upper shape and the orange lower shape just below it – DO YOU SEE HOW THESE BLEND TOGETHER IN THE UPPER IMAGE? Changing the Value of one of those colors would alter this blended effect. The artist can make a choice! TEXTURE IN PAINTING – PAGE 1 Brushstrokes - For smooth and even textures, you can use swift brushstrokes with soft bristles. For a rough texture, brush stokes are hard, broad and impulsive. Dry brush and wet brush techniques are also used for different textures. Brushing with heavy colors creates a heavy texture, while mild textures can be done by gliding the brush smoothly. Shading is one of the most important aspect of building texture in the painting. Painting Surface - A rough canvas or recycled paper gives different effect than smooth papers. You can choose to paint on glass, wood, walls, rags, newspaper, carpet, other found objects, and any sort of surface to affect texture. Paint & Painting Tools - Acrylic paints, oil paints, fabrics and water colors are different forms of media used to create texture. Adding coats, scraps of material, spraying instead of brushing, splattering paint, stamping, applying tissue paper, washing with other chemicals/solutions (be careful!). You can apply tea leaves, salt, pasta, egg shell, sand, sugar, rice, etc. - Or you can paint with “non-brush” tools (putty knives, fingers, sticks, leaves, etc.) TEXTURE IN PAINTING – PAGE 2 In general, smoother textures are passive, decorative, and spatially static, while rough textures are active, emotive, and spatially dynamic. Notice the difference in texture in these famous paintings: Van Gogh, Starry Night Dali, Persistence of Time SIZE & PROPORTION IN PAINTING – PAGE 1 Proportion is the comparative relationship between two or more elements in. With Painting, this can involve numerous elements, including size, color, value, types of shapes, quantity of objects, degree, setting, etc. Proportion is about the sizing and distribution of those element or other objects. Size is also about the total dimensions of your art work, or the overall size of the “canvas.” When deciding on this type of size for your work, make sure to align your decision with principles (Emphasis, Balance, Unity, etc.) AND also with your purposes or reasons for making the art. (Is you message “BIG”?) When proportion is applied within a painting (regardless of the painting’s total size) it is often focused on relationships of the size of one element compared to the size of another related element. This can involve planned differences between: Height, Width, Depth One area of the surface compared to another area The spacing of differences in an element (rough vs. smooth textures in the work) The spacing between objects (filled vs. empty space, for example) SIZE & PROPORTION IN PAINTING – PAGE 2 An example of the effective use of size and proportion Size of object and spaces for elements • The Sky is 50% • Then, the Mountain is 50-66% of the bottom half • Then, wagons, horses, people diminish in size Also notice: • Two main lines that divide the painting are diagonal = action • color/value employs hue for a message (where are they going?) MAKING A PAINTING FOR YOUR PREMIER IN THE ARTS! Study and research the elements of painting that have been presented here, then look for others in your own research. Decide how you can focus on the Principles by using the elements. Try to blend your manipulation of the elements to achieve the principles you have selected. Plan your work– schedule extra time to paint. Keep notes, especially when things DON’T go as planned. When you have made the art work, work on your presentation. Tell the story of your journey (word process it for submission via Campus Cruiser). Prepare how you will show your work. You can project it in the classroom, but it may be best to frame it for viewing Return to MENU when you present to the class. POETRY– THE ELEMENTS Meter Simile & Metaphor Rhyme Diction METER IN POETRY – PAGE 1 In verse and poetry, METER is a recurring pattern of stressed (accented, or long) and unstressed (unaccented, or short) syllables in lines of a set length. For example, suppose a line contains ten syllables (which is the set length of that line) in which the first syllable is unstressed, the second is stressed, the third is unstressed, the fourth is stressed, and so on until the line reaches the tenth syllable. The line would look like the following one (the opening line of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18) containing a pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables. Shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY? Each pair of unstressed and stressed syllables makes up a unit called a foot. The line contains five feet In all: 1 2 3 4 5 Shall I comPARE thee TO a SUM mer’s DAY? METER IN POETRY – PAGE 2 A “foot” is the first term of poetic meter. In all, there are six types of feet: Iamb (Iambic) Unstressed + Stressed Two Syllables Trochee (Trochaic) Stressed + Unstressed Two Syllables Spondee (Spondaic) Stressed + Stressed Two Syllables Anapest (Anapestic) Unstressed + Unstressed + Stressed Three Syllables Dactyl (Dactylic) Stressed + Unstressed + Unstressed Three Syllables Pyrrhic Unstressed + Unstressed Two Syllables The next term of meter is the length of lines, defined by the number of feet (not the “foot” quality). There are eight basic types of meter length: Monometer = One Foot Pentameter = Five Feet Dimeter = Two Feet Hexameter = Six Feet Trimeter = Three Feet Heptameter = Seven Feet Tetrameter = Four Feet Octameter = Eight Feet METER in poetry is defined by the quality of a foot + the number of feet. METER IN POETRY – PAGE 3 (EXAMPLES) Iambic Pentameter (from Milton’s On His Blindness): When I consider how my life is spent Ere half my days in this dark world and wide Unstressed + Stressed x 5 Anapestic Tetrameter (from Byron’s The Destruction of Sennacherib): The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold. And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold. And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea. Unstressed + Unstressed + Stressed x3 Mixed Meter (from Wordsworth’s Intimations of Immortality): It is not now as it has been of yore; Iambic Pentameter Turn where so e’er I may, Iambic Trimeter By night or day, Iambic Dimeter The things which I have seen I now can see no more. Iambic Hexameter Which Principles of Art Works are affected by mixed meter? SIMILE & METAPHOR IN POETRY Metaphors carry meaning from one word or idea “across” to another word or idea, to show that seemingly unrelated words are connected by an important or essential idea or essence they have in common. Initially, metaphors are about connotations. But there are visual metaphors in poetry as well… l(a... (a leaf falls on loneliness) e.e. cummings Use the power of both connotative and visual metaphors as an element of poetry l(a le af fa ll s) one l iness Why do the words fall down the page? Why is there space between some parts of the words? RHYME IN POETRY – PAGE 1 Rhyme is perhaps the most recognizable convention of poetry, but its function is often overlooked. Rhyme helps to UNIFY a poem by repeating a sound that links one concept to another, thus giving structure to a poem. In contemporary poetry, where conventions aren't as rigidly prescribed as in cultures past, rhyme can indicate a poetic theme or a structure to what might seem chaotic. Rhyme works closely with meter! There are varieties of rhyme: internal rhyme functions within a line of poetry; end rhyme occurs at the end of the line; also, true rhymes (bear, care) and slanted rhymes (lying, mine). There are also a number of predetermined rhyme schemes. RHYME IN POETRY – PAGE 2 A Rhyme scheme is a regular pattern of rhyme, one that is consistent throughout the extent of the poem. Rhyme schemes are labeled according to their rhyme sounds. Dulce Et Decorum Est, Wilfred Owen End Rhyme Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, a Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, b Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs a And towards our distant rest began to trudge. b End Rhyme Internal Rhyme? Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, a Yes Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore — b No While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, c Yes As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. b Yes & No “’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door — Only this and nothing more.” b Yes The Raven, Edgar Allen Poe DICTION IN POETRY – PAGE 1 The language of poetry is sometimes different from the language of everyday life. Poets may set their language apart by choosing archaic words, or they may use Latinate diction ("Propitious Heaven," "ethereal plain") rather than more familiar Anglo-Saxon words. They may employ devices such as "periphrasis," in which a simple term is avoided by constructing a more roundabout alternative (one of the most famous is "the finny tribe" instead of "fish"). Diction refers to both the choice and the order of words. It has typically been split into vocabulary and syntax. The basic question to ask about vocabulary is "Is it simple or complex?" The basic question to ask about syntax is "Is it ordinary or unusual?" Taken together, these two elements make up diction. Poets may employ more than one kind of diction in a poem, perhaps setting one speech pattern off against another to achieve a particular effect. (see the next slide…) DICTION IN POETRY – PAGE 2 Twice in this poem, Hughes quotes a blues song; when he does, he uses words like "I's," "gwine," "ma," and "mo." But dialect words such as these do not appear in the rest of the poem, which is composed in standard written English. Notice the importance of repetition of lines, the blues lyrics, and the shift in diction. What difference does it make that the persona who observes the blues singer in the poem uses more formal, educated language than the singer himself does? Is there anything else in the poem that seems to suggest that the speaker is not fully a part of the scene he describes? In line 13, what metaphorical meanings can you apply to “raggy?” 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 Droning a drowsy syncopated tune, Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon, I heard a Negro play. Down on Lenox Avenue the other night By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light He did a lazy sway .... He did a lazy sway .... To the tune o' those Weary Blues. With his ebony hands on each ivory key He made that poor piano moan with melody. O Blues! Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool. Sweet Blues! Coming from a black man's soul. O Blues! In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan-"Ain't got nobody in all this world, Ain't got nobody but ma self. I's gwine to quit ma frownin' And put ma troubles on the shelf." Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor. He played a few chords then he sang some more-"I got the Weary Blues And I can't be satisfied. Got the Weary Blues And can't be satisfied-I ain't happy no mo' And I wish that I had died." And far into the night he crooned that tune. The stars went out and so did the moon. The singer stopped playing and went to bed While the Weary Blues echoed through his head. He slept like a rock or a man that's dead. The Weary Blues - Langston Hughes (1923) MAKING A POEM FOR YOUR PREMIER IN THE ARTS! Study and research the elements of poetry that have been presented here, then look for others in your own research. Manipulate the Meter, Rhyme Scheme, Diction, and use of Metaphor just like a painter manipulates colors, values, and lines. They are tools that should help you address the Principles you are working with. Don’t’ forget the power of visual metaphors… how will you “layout” your poem on the page? When you have made the art work, work on your presentation. Tell the story of your process (word process it for submission via Campus Cruiser). Decide how you will share your poem. The best option is to “sound it out” by reading it live, but always include the written version in your Campus Cruiser submission. Return to MENU PLAYS (THEATRICAL DRAMA) – THE ELEMENTS Action/Plot Character Language/Dialogue Scene(ry) ACTION/PLOT IN THEATRE The events of a play; the story as opposed to the theme; what happens rather than what it means. The plot must have some sort of unity and clarity by setting up a pattern by which each action initiating the next rather than standing alone without connection to what came before it or what follows. In the plot of a play, characters are involved in conflict that has a pattern of movement. The action and movement in the play begins from the initial entanglement, follows through rising action, the climax action, then the falling action into resolution. Write the point of attack into your plot, the main action by which all others will arise. It is the point at which the main complication is introduced. CHARACTER IN THEATRE These are the people presented in the play that are involved in the perusing plot. Each character should have their own distinct personality, age, appearance, beliefs, socio economic background, and language. Plays can have one character, or many, determined by your purpose and by the action needed for your plot. A CHARACTER SPEAKS TO GET WHAT S/HE WANTS. All characters have dreams that make him or her unique. How are they fulfilled? How are they not fulfilled? How do they turn in on themselves? A character should be off-balance in some way. Real characters are excessive in some areas, deficient in others. If there is no disparity between what your characters are saying and what they are doing, you probably aren’t writing theatre. LANGUAGE/DIALOGUE IN THEATRE When composing a short play, avoid writing an exposition! Just jump into your story. This presents a puzzle for the audience to unravel and allows them to play with you. Remember—we are fascinated by the unknown! Don’t provide too much information at once. Let things flow slowly and plan how much you reveal, and when. Break up dialogue with action (you can write movement for character in parentheses in the script). Just as in music, silence is meaningful! Character is shown by dialogue, but don’t rely on slang or stereotypes to carry the action. Look at plays to see how the script looks on the page. Mimic a standard format. PLOT, CHARACTER, DIALOG – A COMPARISON This “play” or scene is ABOUT a communication problem, not the subject matter of the script. Notice how the “point of attack” in the plot comes after a brief exposition/introduction. Notice how each character is focused on what he wants, and also “off balance” in different ways. Notice how, in the second version, the plot and problem of the scene is the same – it is ABOUT the same issue, communication. Notice how the dialogue is adjusted to fit the characters. The language is different, but the “character types” are the same. Finally, notice that, in this case, the scene or staging is equal between both (our next element). SCENE & SCENERY IN THEATRE There are two connotations of the word scene in theatre. One is a part of the whole, a segment of an act of the total play. The other is the setting or scenery. Scene-as-Setting involves scenery, costumes, and special effects in a production, all of the visual elements of the play created for theatrical event. Here, scene is the playwright’s creation of an atmosphere or context for the audience’s eye. When your play begins, the reader or director/actor wants to know the Setting and who and what is seen on stage. This description is usually a non-spoken part of the play, written in parentheses in the script. Look for example plays online to see how this is done. Describing the scene is vital, even when the performance of the your play may not include scenery and costumes. MAKING A PLAY FOR YOUR PREMIER IN THE ARTS! Study and research the elements of PLAYWRIGHTING that have been presented here, then look for others in your own research. Decide how to focus on the Principles by using the elements. Plan your work– schedule extra time. Read your dialogue out loud to see if it works and makes sense. When you have made the play, work on your presentation. Tell the story of your process (word process it for submission via Campus Cruiser). Are you going to read the play? Are you going to ask classmates to read part of it? Are you going to shoot a video of your own enactment at home and then project Return to the video in class? NOTE - You may have to share only an excerpt MENU because of time limits. MUSIC – THE ELEMENTS ♪ Melody ♪ Tempo & Meter ♪ Texture ♪ Dynamics MELODY IN MUSIC ♪ A melody is also called a tune, voice, or line, and is a linear succession of tones which is perceived as a single entity. ♪ Melodies are described by their melodic motion, the intervals between pitches (conjunct or disjunct), the pitch range, or with regard to tension and release, continuity and coherence, cadence, and/or shape. ♪ In general, good melodies build to a climax at some point, then resolve. However, if the melody is written for a song its shape may be unique, and sometimes composers intentionally control a melody for some other type of expressive purpose. If you want to practice creating melodies with an interesting, FREE, SAFE, online tool – and one that does NOT require you to read or write musical notation… CLICK HERE TEMPO & METER IN MUSIC • Tempo is the rate or speed of the beat; fast or slow, and all the variations in between. • Meter is the pulse of the groupings of beat. The basic meters of music are duple and triple, where the pulse is divisible by 2(duple), or where the pulse is divisible by 3 (triple). • In the examples to the right, the METER is constant – it is a march, and it is in a duple meter. However, the TEMPO is different , as well as the instrument(s) playing. You can choose a Meter for your work and then alter the tempo to create motion and movement. You can switch meters to create Contrast or affect the sense of Unity and Balance. TEXTURE IN MUSIC – PAGE 1 ♪ One definition of texture refers to a "structure of interwoven fibers." In music, texture refers to the way multiple voices (or instruments) interact in a composition. One may also think of texture as a description of musical hierarchy: which voice is most prominent? Are all the voices equal? ♪ There are multiple ways of describing texture in music, but we can focus on four basic types: Monophonic - Polyphonic - Homophonic - Heterophonic NOTE – As you look through the following slides and examples, remember that it is not always easy to detect the texture of a piece of music. Whereas monophonic is fairly transparent, polyphony and homophony often sound similar and may need further investigation to differentiate. It is easy to generalize that all popular styles are homophonic, but polyphony occurs occasionally as a result of the interaction of various parts. On the other hand, orchestral music-such as a symphony-may sound polyphonic, but very often there is a dominant melody; it's just obscured by the busyness of the accompanying parts. Also, orchestral music sometimes contains moments of monophonic texture to emphasize a particular melody. Careful listening and practice will aid in the discernment of musical texture. TEXTURE IN MUSIC – PAGE 2 Monophonic Literally meaning "one sound," monophonic texture (noun: monophony) describes music consisting of a single melodic line. Whether it is sung/played by one person or many, as long as the same notes and rhythms are being performed, monophonic texture results. Example of monophonic texture = ♪ Unison singing at a religious service ♪ "Happy Birthday" at a birthday party ♪ A lone bugle playing "Taps" ♪ The singing of "The Star-Spangled Banner" at a baseball game ♪ A composition for solo flute Polyphonic Literally "many sounds," (noun: polyphony) describes a musical texture where 2 or more melodic lines of relatively equal importance are performed simultaneously. If sung, polyphony requires a group of musicians, but it can be played on some instruments by one musician (piano, organ, guitar). Example of monophonic texture = ♪ A round or canon (Row Your Boat, or Three Blind Mice) ♪ Vocal and instrumental music from the Renaissance through the Baroque ♪ Music for large instrumental ensembles ♪ Religious choral music Monophony sounds and looks like this: Polyphony sounds and looks like this: Click to Hear Click to Hear TEXTURE IN MUSIC – PAGE 3 Homophonic Homophonic (or homophony) is the texture we encounter most often. It consists of a single, dominating melody that is accompanied by chords. Sometimes the chords move at the same rhythm as the melody; other times the chords are made up of voices that move in counterpoint to each other. The important aspect is that the chords are subservient to the melody. Example of monophonic texture = ♪ Hymn singing during a religious service ♪ Most popular music styles (rock, folk, country, jazz, etc.) ♪ Accompanied vocal music from the Middle Ages to the present Homophony sounds and looks like this: Heterophonic Heterophonic texture is rarely encountered in “western” music. It consists of a single melody, performed by two or more musicians, with slight or not-so-slight variations between those performers. These variations usually result from ornamentation being added spontaneously (improvisation) by the performers. Heterophony is mostly found in the music of non-”western” cultures such as Native American, Middle Eastern, Asian, and South African. Heterophony sounds and looks like this: Click to Hear Click to Hear DYNAMICS IN MUSIC Sounds, including music, can be barely audible, or loud enough to hurt your ears, or anywhere in between. When they want to talk about the loudness of a sound, scientists and engineers talk about amplitude. Musicians talk about dynamics. In the sciences, the amplitude of a sound is a particular number, usually measured in decibels, but in music dynamics are relative; an orchestra playing fortissimo sounds much louder than a single violin playing fortissimo. In any case, composers use dynamic contrasts to create Contrast and a sense of Movement or energy. Watch and Listen for loud-to-soft contrasts Here is a film scene in which you can hear HUGE musical dynamic contrasts in Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55 "Eroica“ With the added benefit of showing you the typical setting in which this music was originally performed --- as well as the composer’s typical personality --- MAKING A PIECE OF MUSIC FOR YOUR PREMIER IN THE ARTS! Study and research the elements of Music that have been presented here, then look for others in your own research. Decide how to focus on the Principles by using the elements. Plan your work– schedule extra time. When you have composed your music, work on your presentation. Tell the story of your process (word process it for submission via Campus Cruiser). Prepare how you will share your work. Will you perform it live, yourself? Will you ask friends to visit class and perform with you? Will you record it and play in back for the class using the equipment in the room? Return to NOTE – you do NOT have to notate your music, MENU a recording or live performance is sufficient. INSTRUCTIONS For each elements sections, 5 total slides: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Element 1 with examples Element 2 with examples Element 3 with examples Element 4 with examples Titled “Making a xxx for YOUR Premier in the Arts Project”. Give instructions (“If you make a xxxx…”), giving LINKS to other elements information, then explaining what to do for the class presentation (‘if music, play live or play recorded music’ – etc)