Word Structure

advertisement

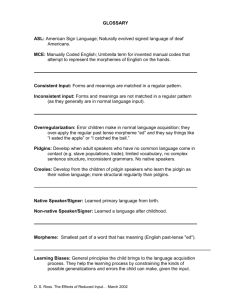

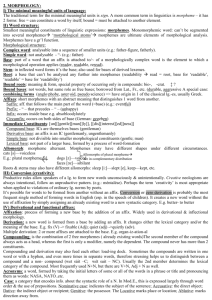

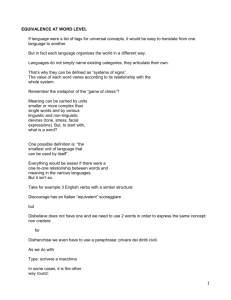

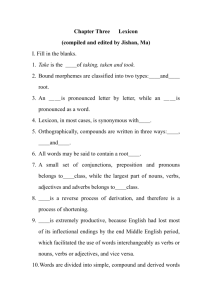

Word Structure Part 1 The Structure of Words: Morphology • Fundamental concepts in how words are composed out of smaller parts • The nature of these parts • The nature of the rules that combine these parts into larger units • What it might mean to be a word Today I. Morphemes II. Types of Morphemes III. Putting Morphemes together into larger structures – Words with internal structure – Interesting properties of compounds I. Morphemes • Remember that in phonology the basic distinctive units of sound are phonemes • In morphology, the basic unit is the morpheme • Basic definition: A morpheme is a minimal unit of sound and meaning (this can be modified in various ways; see below) Some Examples • Many words can be divided into smaller parts, where the parts also occur in other words: dogs walking blackens player-hater dog-s walk-ing black-en-s play-er hat-er Compare: cat-s; runn-ing; dark-en-s; eat-er (note: in some cases there are spelling changes when we add morphemes; ignore this) Parts, cont. • The smaller parts occur consistently with many words: – -s: forms the plural consistently – -ing: forms a noun from a verb – -en: forms a verb meaning ‘become ADJ’ from an adjective ADJ – -er: forms an agentive nominal from a verb, a person or thing who does that activity Consistent Sound/Meaning • Notice that this is not the only way we can divide up words into smaller parts; consider – Tank, plank, flank, drank, rank, etc. • In these words, we could easily identify a component -ank • However, this is not a morpheme – There is no consistent meaning with this -ank – The “leftover” pieces t-, pl-, fl-, dr-, r- are not morphemes either Connections between Sound and Meaning • Remember that a phoneme sometimes has more than one sound form, while being the same abstract unit: /p/ with [p] and [ph] • A related thing happens with morphemes as well • In order to see this, we have to look at slightly more complex cases Morphemes and Allomorphs • We will say in some cases that a morpheme has more than one allomorph • This happens when the same meaning unit like [past] for past tense or [pl] for plural has more than one sound form – Past: one feature [past] • kick / kick-ed • leave / lef-t • hit / hit-Ø • The last example shows a case in which the phonological form of the morpheme past is zero, i.e. it is not pronounced Allomorphy, cont. • In the case of phonology, we said that the different allophones of a phoneme are part of the same phoneme, but are found in particular contexts • The same is true of the different allomorphs of a morpheme • Which allomorph of a morpheme is found depends on its context; in this case, what it is attached to: – Example: consider [pl] for English plural. It normally has the pronunciation –s (i.e. /z/), but • moose / moose- Ø • ox / ox-en • box/*box-en/box-es • So, the special allomorphs depend on the noun An Additional Point: Regular and Irregular • In the examples above, the different allomorphs have a distinct status. One of them is regular. – This is the default form that appears when speakers are using e.g. new words (one blork, two blorks) – For other allomorphs, speakers simply have to memorize the fact that the allomorph is what it is – Example: It cannot be predicted from other facts that the plural of ox is ox-en – Demonstration: The regular plural is /z/; consider one box, two box-es. • Default cases like the /z/ plural are called regular. Allomorphs that have to be memorized are called irregular. • Irregular allomorphs block regular allomorphs from occurring (ox-en, not *ox-es or *ox-en-s). Two types • There are in fact two types of allomorphy. Think back to phonology… – The Plural morpheme in English has different sound-forms: dog-s/cat-s/church-es • These are predictable, based on the phonological context – In the case of Past Tense allomorphy, it is not predictable from the phonology which affix appears • We can find verbs with the same (or similar) sound form, but with different allomorphs: break/broke, not stake/*stoke • If you think about this case for a while, though, you will notice some patterns; more on this later II. Morpheme Types We’ll now set out some further distinctions among morpheme types • Our working definition of morpheme was ‘minimal unit of sound and meaning’ • A further division among morphemes involves whether they can occur on their own or not: – No: -s in dog-s; -ed in kick-ed; cran- in cran-berry – Yes: dog, kick, berry Some Definitions • Bound Morphemes: Those that cannot appear on their own • Free Morphemes: Those that can appear on their own • In a complex word: – The root or stem is the basic or core morpheme – The things added to this are the affixes – Example: in dark-en the root or stem is dark, while the affix– in this case a suffix– is -en Further points • In some cases, works will use root and stem in slightly different ways • Affixes are divided into prefixes and suffixes depending on whether they occur before or after the thing they attach to. Infixes-- middle of a word (e.g. fan-f*ing-tastic) • For the most part, prefixes and suffixes are always bound, except for isolated instances Content and Function Words Another distinction: • Content Morphemes: morphemes that have a referential function that is independent of grammatical structure; e.g. dog, kick, etc. – Sometimes these are called “open-class” because speakers can add to this class at will • Function morphemes: morphemes that are bits of syntactic structure– e.g. prepositions, or morphemes that express grammatical notions like [past] for past tense. – Sometimes called “closed-class” because speakers cannot add to this class Cross-Classification • The bound/free and content/function distinctions are not the same. Some examples: Content Function Bound cran- -ed Free dog the Aside: Non-Affixal Morphology • In the cases above, we have seen many affixes associated with some morphological function • In other cases, there are additional changes; e.g., changes to the stem vowel: – sing/sang – goose/geese • Examples of this type are not obviously affixal, as there is no (overt) added piece (prefix or suffix). Rather, the phonology of the stem/root has changed Some examples • Stem changing: Present Past Participle sing sang sung begin began begun sit sat sat come came come Another pattern • While in many cases the stem change does not co-occur with an affix, in some cases it does: Examples: break broke brok-en tell tol-d tol-d freeze froze froz-en Use of stem changing patterns • In some languages, stem-changing is much more important than it is in e.g. English • In Semitic languages, extensive use is made of different templatic patterns, that is, abstract patterns of consonants and vowels: – Arabic noun plurals: • kitaab ‘book’; kutub ‘books’ • nafs ‘soul’; nufus ‘souls’ III. Internal structure of words • Words have an internal structure that requires analysis into constituents (much like syntactic structure does) • For example: – Unusable contains three pieces: un-, use, -able • Question: If we are thinking about the procedures for building words, is the order – derive use-able, then add un-; or – derive un-use, then add -able Word Structure Possibilities: Structure 1 Structure 2 un use able un use able Word Structure, Cont. • Consider: – With –able, we create adjectives meaning ‘capable of being V-ed’, from verbs V • Break/break-able; kick/kick-able – There is no verb un-use – This is an argument that Structure 1 is correct: [un [use able]] – This analysis fits well with what the word means as well: not capable of being used. Structure two would mean some thing like ‘capable of not being used’ Another example • Consider another word (from the first class…): unlockable. Focus on un• Note that in addition to applying to adjectives (clear/unclear) to give a “contrary” meaning, unapplies to some verbs to give a kind of “undoing” or reversing meaning: do, undo zip, unzip tie, untie • Note now that unlockable has two meanings The Unlockable example • Two meanings: 1) 2) Not capable of being locked Capable of being unlocked These meanings correspond to distinct structures: 1) un lock 2) able un lock able Unlockable, cont. • The second structure is one in which –able applies to the verb unlock • This verb is itself created from un- and lock • The meaning goes with this: ‘capable of being unlocked’ • In structure 1, there is no verb unlock • So the meaning is ‘not capable of being locked’ Some General Points • The system for analyzing words applies in many cases that are created on the fly • Complex words and their meanings are not simply stored; rather, the parts are assembled to create complex meanings • Another example of the same principle applies in the process of compounding Introduction to Compounding • A compound is a complex word that is formed out of a combination of stems (as opposed to stem + affix) • These function in a certain sense as ‘one word’, and have distinctive phonological patterns • Examples: olive oil shop talk shoe polish truck driver Note that the different elements in these compounds relate to each other in different ways... Internal structure • Like with other complex words, the internal structure of compounds is crucial • There are cases of ambiguities like that with unlockable • Example: obscure document shredder 1) Person who shreds obscure documents [[obscure document] shredder] 2) Obscure person who shreds documents [obscure [document shredder]] Compounding, cont. • An interesting property of compounds is that although they are ‘words’, they form a productive system, without limits (as far as grammar is concerned, not memory). • Note also that compounds have special accentual (stress) properties: judge trial judge murder trial judge murder trial judge reporter murder trial judge reporter killer murder trial judge reporter killer catcher murder trial judge reporter killer catcher biographer murder trial judge reporter killer catcher biographer pencil set …