Welcome to Econ 1 - Bakersfield College

advertisement

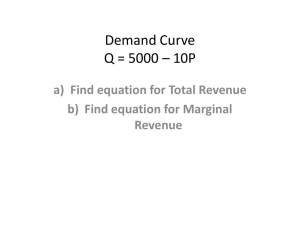

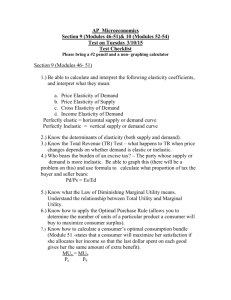

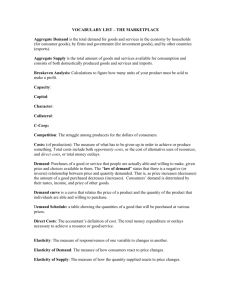

Welcome to Day 10 Principles of Microeconomics Price elasticity is the ratio of the percent change in quantity demanded to the percent change in price. Elasticity of demand = percent change in quantity demanded divided by percent change in price. Ed = %Qd % P So a t-shirt shop notices that when they raise their price by 5%, they lose 10% of their customers. What is their elasticity of demand? -10% = -2 5% What does the -2 mean? For every 1 percent they raise their price, their sales drop by 2%. The elasticity of demand number always means that for every 1% they raise their price, their sales drop by X% Another store checks their data and sees when they raise their price by 10%, they lose 5% of their sales. What is their elasticity of demand? -5% = -0.5 10% For every 1% they raise their price, they lose 0.5% of their sales. What if the stores lowered their price? Then a store with an elasticity of -2 should gain 2% in sales for every 1% drop in price. A store with an elasticity of -0.5 should gain 0.5% more sales with every 1 percent drop in price. Unfortunately, the data does not usually come in percentage terms. Usually you know the starting and ending prices, and the starting and ending quantities, and have to convert these to percentages. Here’s how to do that. %Qd = (Q2-Q1)/[(Q1+Q2)/2] %P = (P2-P1)/[(P1+P2)/2] So the elasticity formula in all its glory is Ed = (Q2-Q1)/[(Q1+Q2)/2] (P2-P1)/[(P1+P2)/2] The textbook writes it this way Q / Q eD P / P Notice that we are calculating percentage changes in an unusual way. Usually, you would just divide the change by the starting value, not the average of the starting and ending value. By doing it this way, we get the same elasticity answer if the price goes up from $10 to $12 or down from $12 to $10. The own price elasticity number will always be negative by the math, but it is common to drop the negative sign and write it as its absolute value. So -2 becomes 2. What is the range of possible own price elasticities? 0 Ed < 1 then Inelastic Demand Ed > 1 then Elastic Demand Ed = 1 then Unit 1 Elastic Demand 8 Total Revenue for a store is TR = P x Q Imagine a store with a very inelastic demand, say 0.3 If they raise their price 10%, their sales drop by 3%. Does their revenue go up or down? TR ? = P 10% x Q 3% TR goes up. Whenever the elasticity is below 1, the percent drop in purchases is always less than the percent rise in price and revenue always rises when price rises. What if the elasticity is greater than one? Then the percentage drop in sales is always greater than the percent rise in price and the revenue always fall. TR ? = P 3% x Q 10% TR goes down. Inelastic Demand Raise price revenue goes up. Lower price revenue goes down. Elastic Demand Raise price revenue goes down. Lower price revenue goes up. And if the demand is unit elastic? Then the percentage change in price equals the percentage change in sales, and revenue remains unchanged. Unit Elastic Demand (Ed = 1) Raise price revenue stays the same. Lower price revenue stays the same. What happens if zero customers stop buying when the price rises? Ed = %Qd % P Ed = 0. This is called perfectly inelastic demand. Note that an Ed = 0 does not mean the store has 0 customers, it means it loses 0 customers then it raises its price. And what if the store loses every customer when it raises its price the tiniest possible amount? Ed = %Qd % P As %P goes to 0, %Qd stays constant. This fraction is going to infinity. Perfectly Inelastic Demand Curve Perfectly Elastic Demand Curve What determines if the elasticity is high or low? 1) Number and closeness of substitutes. 2) Percentage of budget spent on the good. 3) Time. 1) Number and closeness of substitutes. The more and better substitutes available for a good, the more consumers buy these substitutes in place of the good when the price of the good rises. Good substitutes Poor substitutes high elasticity low elasticity Tell me some high and low elasticity items. 2) The percentage of your budget spent on the good. When the price of the car you are thinking of buying doubles, you are more likely to back off buying it than when the price of a candy bar doubles. The greater the percentage of your budget spent on the good, the higher its elasticity of demand. 3) Time The more time you have to respond, the higher the elasticity of demand. What can you do if the price of gas rises? The textbook tells us that the short-run elasticity of demand for oil in the United States is .06, but the long-run elasticity is .45 Reviewing the 3 factors that determine elasticity of demand. 1) Number and closeness of substitutes. 2) Percentage of budget spent on the good. 3) Time. What we learned today. 1. What own price elasticity is and how to calculate it. 2. What inelastic and elastic demand mean and how they affect revenue when price rises. Welcome to Day 11 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. What own price elasticity is and how to calculate it. 2. What inelastic and elastic demand mean and how they affect revenue when price rises. Income elasticity of demand is the percentage change in quantity demanded at a specific price divided by the percentage change in income that produced the demand change, all other things unchanged. Ei = %D D = Demand % I I = Income What does the income elasticity number tell you? It is the percent change in purchases if there is a 1 percent rise in income. For example, an answer of 0.7 means for every 1% rise in income, people buy 0.7 percent more of the good. When the income elasticity is positive, that means people buy more of the good when their income goes up or less when their income goes down. In other words, a normal good. When the income elasticity is negative, people buy less when their income goes up, in other words, an inferior good. Cross price elasticity of demand is the percentage change in the quantity demanded of one good or service at a specific price divided by the percentage change in the price of a related good or service. EX,Y = %Dx % Py Remember how to find the percentage change in X. It is the change in X divided by the average of the starting and ending quantities of X. And don’t forget to check for the sign. Cross-price elasticity is positive when the two goods are substitutes. It is negative when the two goods are complements. Price elasticity of supply is the ratio of the percentage change in quantity supplied of a good or service to the percentage change in its price, all other things unchanged. % change in quan sup e s % chang in pric The terminology from the elasticity of demand transfers over to the elasticity of supply. Es > 1 is Elastic Supply Es < 1 is Inelastic Supply Es = 0 is Perfectly Inelastic Supply Es = Infinity is Perfectly Elastic Supply. Supply Curves and Their Price Elasticities The more time suppliers have to build more factories, the greater the increase in the amount of the good will be in response to a given higher price. Which supply curve has the larger elasticity? S1 P2 S2 P1 Q Cars Elasticity and the War on Drugs How can we spend so much money and manpower and drugs still be so readily available? http://www.drugsense.org/cms/wodclock How do we represent the war on drugs in a supply and demand diagram? Is the elasticity of demand for most illegal drugs going to be high or low? Does cocaine have good substitutes or few substitutes? D1 is low elasticity. D2 is high elasticity. $70.00 $60.00 $50.00 $40.00 P2 P1 $30.00 $20.00 D2 $10.00 D1 $0.00 0 100000 Q2B Q2AQ1 200000 300000 How much cocaine has been destroyed? What is the drop in usage? $70.00 $60.00 S2 $50.00 P2 S1 $40.00 $30.00 P1 $20.00 $10.00 D $0.00 0 100000 Q2 Q1 200000 300000 Q1 to Q2 is the drop in usage = 25,000 Amount destroyed = 125,000 $70.00 $60.00 S2 $50.00 P2 Amt. Destroyed $40.00 S1 $30.00 P1 $20.00 $10.00 D $0.00 0 100000 Q2 Q1 200000 300000 So what has happened? Used to be 150,000 made and bought for 20 bucks. Now 250,000 is made, half is destroyed, and 125,000 is bought for $40. The main effect of destroying drugs in this model is that more is made. What is the elasticity of cocaine in this model? Q1-Q2/[(Q1+Q2)/2] divided by P2-P1/[(P1+P2)/2] is (25,000/ 137,500)/(20/30) = .18/.67 = .2 What if the elasticity is high? Q1 to Q2 is the drop in usage = 60,000 Amount destroyed = 90,000 $60.00 S2 $50.00 S1 $40.00 P2 P1 Amt. Destroyed $30.00 $20.00 D $10.00 $0.00 0 100000 Q2 200000 Q1 300000 What is the elasticity of cocaine now? Q1-Q2/[(Q1+Q2)/2] divided by P2P1/[(P1+P2)/2] is (60,000/120,000)/(6/23) = .5/.26 = 1.92 Notice how much more the price rises when the elasticity is low. What are some side effects of cocaine prices going high? Now let’s look at the effect of government subsidized student loans. Students are given $300,000,000 to go to college (doubling current tuition spending) Tuition $9,000.00 $8,000.00 S $7,000.00 $6,000.00 $5,000.00 $4,000.00 D2 $3,000.00 $2,000.00 D1 $1,000.00 $0.00 0 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 Number Students Number of students rises from 100,000 to 130,000. Tuition rises from $3,000 to $5,600. Everyone gets to pay the higher tuition, not just the additional students. And don’t forget, these are loans, so you still have to pay the money back. So who is helped more by government guaranteed loans? The students … or the colleges and banks? And this result is because of elasticity of supply. What if elasticity of supply is high? $8,000.00 $7,000.00 $6,000.00 $5,000.00 S $4,000.00 $3,000.00 D2 $2,000.00 D1 $1,000.00 $0.00 0 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 What we learned today. 1. What income elasticity and cross price elasticity are. 2. How elasticity of demand determine the effectiveness of the war on drugs and student loan programs. Welcome to Day 12 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. What income elasticity and cross price elasticity are. 2. How elasticity of demand determine the effectiveness of the war on drugs and student loan programs. We’re skipping chapters 6 and 7 for now, but we will come back to ch. 6 at the end of this unit and ch. 7 at the end of the class. Instead we’re moving to chapter 8 to talk about production and cost. We’ve already seen in our elasticity of supply discussion that time matters for how much is produced. Two Time Frames Short-Run: Some inputs are fixed Long-Run: All inputs are variable Marginal Product of Labor (MPL) is the increase in total output gained by adding one more worker. Q/L N 0 Q 0 MPL 20 1 20 30 2 50 25 3 75 10 4 85 N 0 Q 0 MPL 20 1 20 30 2 50 25 3 75 10 4 85 Why would MPL be rising? Specialization of Labor 1) Take advantage of natural abilities. 2) More practice and training at specific jobs. 3) Less time lost walking between jobs. N 0 Q 0 MPL 20 1 20 30 2 50 25 3 75 10 4 85 Specialization of Labor Region N 0 Q 0 MPL 20 1 20 30 2 50 25 3 75 10 4 Specialization of Labor Region 85 Why would MPL be falling? Diminishing Returns As more variable factors are added to work with a fixed factor, eventually output rises at a diminishing rate. N 0 Q 0 MPL 20 1 20 30 2 50 25 3 75 10 4 Specialization of Labor Region 85 Diminishing Marginal Returns Region Productivity of Labor Measured in MPL Bushels of Wheat 35 Spec. of 30 Labor Reg. 25 Dim. Mar. Ret. Reg. 20 15 10 5 0 0 1 2 3 Number of Workers 4 5 Now that we know what MPL is, here is a new statistic for you. Average Product of Labor (APL) = Q/N Average-Marginal Rule: When the marginal is above the average, the average rises; when the marginal is below the averge, the average fall. N 0 Q 0 1 20 2 50 3 75 4 85 MPL APL 0 20 20 30 25 25 25 10 21.25 Marginal and Average Product of Labor on the same graph. 35 Bushels of Wheat 30 APL 25 20 15 MPL 10 5 0 0 1 2 3 Number of Workers 4 5 Marginal and Average Product of Labor on the same graph. 35 Bushels of Wheat 30 APL 25 20 15 MPL S.o.L. Region 10 5 D.M.R. Region 0 0 1 2 3 Number of Workers 4 5 Output MPL APL Number Workers What we learned today. 1. What marginal product of labor is. 2. How specialization of labor and diminishing marginal returns determine if MPL is rising or falling. 3. The average-marginal rule and how to graph MPL and APL together. Welcome to Day 13 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. What marginal product of labor is. 2. How specialization of labor and diminishing marginal returns determine if MPL is rising or falling. 3. The average-marginal rule and how to graph MPL and APL together. I told you the productivity story just so I can tell you the cost story. Fixed Costs (don’t change as production varies): Lease Payments Interest on Loans Some Insurance Variable Costs (do change as production varies): Labor Supply Electricity Q 0 1 2 3 4 5 TFC 100 100 100 100 100 100 TVC 0 20 35 60 100 160 TC MC ATC 100 --120 20 120 135 15 67.5 160 25 53.3 200 40 50 260 60 52 If workers cost $10 each, how many workers did the firm hire to build 1 radio? How about 2 radios? Why does it take 2 full workers to make the first radio, but only another 1.5 to make the second radio? The workers must be getting more productive. Why would that be? Why does it take 2 full workers to make the first radio, but only another 1.5 to make the second radio? The workers must be getting more productive. Why would that be? Specialization of Labor Why does it take 4 workers to make radio 4, but 6 workers to make radio 5? Why does it take 4 workers to make radio 4, but 6 workers to make radio 5? Diminishing Marginal Returns Q TFC TVC TC MC ATC 0 100 0 100 --1 100 20 120 20 120 2 100 35 135 15 67.5 3 100 60 160 25 53.3 4 100 100 200 40 50 5 100 160 260 60 52 Above the green line is SoL. Below is DMR. Marginal Cost and Average Total Cost on the same graph. 140 Cost in Dollars 120 ATC 100 80 60 40 MC 20 0 0 2 4 Output 6 8 Marginal Cost and Average Total Cost on the same graph. Dollars Fixed Cost MC ATC Specialization Diminishing Output of labor Marginal Returns In the short-run, the size of the factory is fixed. In the long-run, the size of the factory can be varied. The LRATC is made up of segments of the various possible SRATC curves. Economies of Scale - LRATC is falling as you produce more in a larger factory. Constant returns to Scale - LRATC is staying the same as you produce more in a larger factory. Diseconomies of Scale - LRATC is rising as you produce more in a larger factory Why Economies of Scale? 1) Specialization of Labor 2) Mass Production Techniques – Assembly Lines Why Diseconomies of Scale? Contr 1) Command and Control Problems 2) Law of Increasing Opportunity Cost Problems Would you always want to produce in constant returns to scale since that is the lowest cost of production area? Would you always want to produce in constant returns to scale since that is the lowest cost of production area? No! How many customers you have and how much they are willing to pay matters also. Alright, so you learned all this about productivity and cost. What is the business actually going to do? For that, we have to bring in the customers. Businesses operate in different environments, called market structures. There are 4 market structures. Each market structure is defined by: 1) How many firms sell in it. 2) How close the firms products are to each other. 3) How easy it is to get into or out of the market. The first market structure is “Perfect Competition” 1) Many sellers and buyers. 2) Firms sell identical goods. 3) There is easy entry/exit. Because there are many firms selling identical products, the sales price is the same for all firms. These firms are called Price Takers. Perfect Competition examples are: 1) Small farms. 2) Stockbrokers selling identical stock. 3) Miners. 4) Fishermen A small wheat farmer has a demand curve that looks like this: P Demand Curve $5.98 Q He’s not worried that he will produce so much wheat he will drive the world price of wheat down. The world demand curve for wheat is still downward sloping, but he is too small to make any difference. Just like you buying potato chips. What we learned today. 1. How to graph MC and ATC. 2. What causes economies and diseconomies of scale. 3. What perfect competition is and what its demand curve looks like. Welcome to Day 14 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. How to graph MC and ATC. 2. What causes economies and diseconomies of scale. 3. What perfect competition is and what its demand curve looks like. Marginal Revenue is the increase in total revenue gained with each additional sale. It is a before cost is taken out number. For firms in perfect competition, marginal revenue = price. A small wheat farmer has a marginal revenue curve that looks like this: P $5.98 Marginal Demand = Revenue Curve Curve Q The farmer does not get to pick his price, but he does get to pick his quantity of wheat grown. He will do what makes him the most money. Q 0 1 2 3 4 TR 0 10 20 30 40 TC π Price=$10 2 -2 TR = P x Q 10 0 π = Profit 16 4 TR = Total 25 5 Revenue 37 3 TC = Total Cost Q 0 1 2 3 4 TR 0 10 20 30 40 TC 2 10 16 25 37 π MR MC -2 -- -0 10 8 4 10 6 5 10 9 3 10 12 To maximize profit, produce the wheat that has MR>MC and don’t produce the wheat that has MC>MR. Don’t sell any lemonade that costs more than 10 cents to make. If you can produce fractions rather than just integers, then produce the level of output where MR=MC. This is what the textbook calls the marginal decision rule. Just because you follow the marginal decision rule doesn’t mean you necessarily make a positive profit. Sometimes the best you can do is to lose the least. Q 0 1 2 3 4 TR 0 10 20 30 40 TC 20 28 34 43 55 π MR -20 --18 10 -14 10 -13 10 -15 10 MC -8 6 9 12 What should you do here? Note that you can’t avoid a loss by shutting down. If you shut down, you lose fixed cost. Is there a way to know if you are making a profit or losing money just using the price and the ATC of production? TR = P x Q TC = ATC x Q TR = P x Q TC = ATC x Q The Q’s will be the same for both equations. So if P>ATC, this firm is making money. If P<ATC, this firm is losing money. So how do you graph this all out? First, the marginal decision rule: produce the quantity where MR = MC Produce at Qπ to maximize profit. 14 Cost in Dollars 12 10 MR 8 6 MC 4 2 0 0 1 2 3 Output Qπ 4 5 MC P Pπ MR Q Qπ Here, MC intersects MR twice. Always use the 2nd point of interception. MR, MC, and P are not enough to know if you are making a positive profit. As fixed costs rise, these numbers do not change, yet your profit is falling. You need to add ATC. MC P Pπ ATC MR Q Qπ Here we have profit because P>ATC. MC P Pπ ATC MR Q Qπ Here we have a loss because ATC>P. What we learned today. 1. What MR is and to produce the quantity where MR = MC. 2. The firm makes a profit when P>ATC 3. How to graph the Q and P of a business and if they are making a profit. Welcome to Day 15 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. What MR is and to produce the quantity where MR = MC. 2. The firm makes a profit when P>ATC 3. How to graph the Q and P of a business and if they are making a profit. When should a firm just give up and shut-down? When its loss from operating is greater than its fixed cost. Firm 1 TR $400 TFC $100 TVC $395 TC $495 Profit $-95 Firm 2 $400 $100 $405 $505 $-105 What should each firm do? Keep operating when TR>TVC. TR = P x Q TVC = AVC xQ Keep operating when P>AVC Shutdown when P<AVC P = AVC is the shutdown price. MC P P1 MR Q How much will this firm produce at P1? P P2 P1 P3 MC MR Q Q1 What about at P2 and P3? P P2 P1 P3 MC MR2 MR1 MR3 Q3 Q1 Q2 Q We have marked 3 points on the firms supply curve. Supply Curve P P2 P1 P3=PS Q3 Q1 Q2 Q The firm’s marginal cost curve is its supply curve down to the Shutdown Price (PS) The market supply curve is all the individual supply curves added together. P Individual firm supply curves Market Supply Curve Q Now we add the demand curve and we get where the market price comes from P S PE D Q The market price for wheat is the price such that each farm, in response to that price, wants to grow an amount of wheat which, when all the farms are added together, equals the amount of wheat that customers want to buy at that price. This is what chapter 3 said, also. Now let’s talk about the long-run, so enough time goes by that new farms can enter the market. Before we do so, let’s be a bit more exact about what we mean by cost and profit. Explicit Cost is actual money paid out. Implicit Cost is the value of resources used for which no money is paid. For example: time and already owned land. Accounting profit is Total Revenue minus Explicit Cost. Economic Profit is Total Revenue minus both Explicit and Implicit Cost. The economic profit of a choice can also be understood as how much more you make doing this choice than the next best choice. You are offered $100 to work all day on project A and $60 to work all day on project B. What is your economic profit of choosing A? Suppose woman A and woman B want to start two similar businesses. Woman A has an $80,000 job she would have to quit to run her business, but woman B is unemployed and we count her time as having 0 value. How does this affect their accounting and economic profits? Woman A Total Revenue $100,000 Explicit Cost $60,000 Accounting Profit $40,000 Implicit Cost $80,000 Economic Profit -$40,000 Woman B $100,000 $60,000 $40,000 $0 $40,000 Economic profit is a better predictor of behavior. We would predict woman A will not start this business and woman B will. So now enough time goes by for new wheat farms to open up. When will new farms be started? When wheat farms are making money, that is, have a positive economic profit. How long will the new farms keep coming in? Remember, entry is easy. Till profits go to zero. If profits are negative (in other words, losses), then farms will leave in the long-run until profits are zero. So no matter where you start, profits in the long-run go to zero because of easy entry/exit. So what does the long-run equilibrium look like? Let’s think about how the long-run responds to an increase in demand. Start at a long-run equilibrium with profits for the typical wheat farm at $0. MC ATC P P1 MR=P Q How much will this firm produce at P1? Now there is an increase in market demand and the price rises to P2 in the short-run. P Sshort-run P2 P1 D1 D2 Q P P2 P1 MC ATC MR2=P2 MR1=P1 Q This firm is now making a profit. This attracts entry. P P2 P1 MC ATC MR2=P2 MR1=P1 Q How far will the price have to fall until profit is back to zero? There has to be a new equilibrium back at P1. For this to happen, the long-run supply curve has to be flat. P Sshort-run P2 P1=P3 D1 Q 1 Q2 Q3 D2 SLong-run Q P P2 P1=P3 MC ATC MR2=P2 MR1=P1 MR3=P3 Q And profits are back to zero. BTW, this farm is back to producing where it started, so where is all the additional wheat coming from? What we learned today. 1. When a firm losing money should shutdown (P<AVC or TR<TVC). 2. How firm’s supply curve is its MC curve and market equilibrium. 3. In the long-run, profits go to zero. 4. The long-run equilibrium for the market with perfect competition. Welcome to Day 16 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. When a firm losing money should shutdown (P<AVC or TR<TVC). 2. How firm’s supply curve is its MC curve and market equilibrium. 3. In the long-run, profits go to zero. 4. The long-run equilibrium for the market with perfect competition. But I fear we have proven too much. It looks like in the long-run, price always goes back to where it started, and I don’t believe this. P P2 P1 MC ATC MR2=P2 MR1=P1 Q How can we get back to zero profits as new firms come in with the price ending up higher than P1? P P3 P2 P1 MC ATC2 ATC1 MR2=P2 MR1=P1 Q That’s right. If ATC rises as new firms enter the market. So now P3 will be higher than P1 when ATC rises as new firms enter. P P2 P3 P1 Sshort-run SLong-run D1 Q1 Q2 Q3 D2 Q This case of rising ATC as new firms enter is called an “Increasing Cost Industry”. The first case where ATC stayed constant is called a “Constant Cost Industry”. Which case seems more likely? Could it even be possible that as more firms enter the market, the ATC falls? Think about what happens if wheat farms need tractors, and tractors are made with economies of scale. For this “Decreasing Cost Industry”, the long-run price P3 will be lower than the starting price P1 if there is an increase in demand. This means there must be a downward sloping long-run supply curve. Now P3 is less than P1. And increase in demand has lead to a lower price. P Sshort-run P2 P1 P3 SLong-run Q1 Q2 D1 Q3 D2 Q Let’s review and simplify. Increasing Cost Industry. LRS slopes up. P SLong-run P2 P1 D1 Q1 Q2 D2 Q Constant Cost Industry. LRS slopes straight across. P SLong-run P1=P2 D1 Q1 Q2 D2 Q Decreasing Cost Industry LRS slopes down. P P1 P2 SLong-run D1 D2 Q1 Q2 Q Where does all this leave the law of supply? It is still true that short-run supply curves always slope up. But now this is primarily because of diminishing marginal returns rather than the next worker getting worse. In the long-run, supply curves usually slope up as more resources are used and the workers get worse; but it is possible for the supply curve to slope down if significant inputs are made with economies of scale. As we add more complexity to the model, our previously simple answers grow more complex. Now, back to Chapter 6 Our goal is to answer the 3 fundamental questions well. 1) What to produce? What people want. 2) How to make it? Produce efficiently. 3) Who gets what is produced? People who value it. An economy that does these things is operating efficiently. Efficient The allocation of resources when the net benefits of all economic activities are maximized. An economy that is operating efficiently has both: 1) Efficient production 2) Efficient allocation of goods. Will a market economy do these things? How does a business make money? Producing a lot of what people want the most and selling it. The better a business correctly estimates what its customers value, and makes a lot of those things, the higher its profit. And of course, we want the economy to be able to adjust to changing circumstances. Will a market economy do that? Rainy Winter Increases Demand P $16.00 $14.00 S $12.00 P2 $10.00 P1 $8.00 D2 $6.00 $4.00 D1 $2.00 $0.00 0 100000 Q1 Q2 200000 300000 Q Can a command economy do this? The incentive problem and the information problem. The Incentive Problem What does an umbrella businessman get if he gets umbrellas quickly out to a rainy area? What does the 2nd undersecretary of umbrellas in Washington get if he gets umbrellas quickly out to a rainy area? The Information Problem How does the 2nd Undersecretary of Umbrellas know we need more umbrellas in Bakersfield? How do private business owners of umbrella companies know? Every time you go shopping, it is a transfer of information fest!!! You are letting sellers know what you want. Sellers are letting you know what they can make at what cost. The Invisible Hand Adam Smith – 1776 The Wealth of Nations Because trades are voluntary, in helping yourself, you help others also. The way for the businessman to make money is to most effectively serve his customers. In doing what is best for him, he is being lead, as if by an “invisible hand” to help society. What we learned today. 1. Increasing, constant, and decreasing cost industries and the slope of the long-run supply curve. 2. Operating Efficiency, which is broader than production efficiency. 3. How the market economy solves the incentive and information problems – “The Invisible Hand”. Welcome to Day 17 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. Increasing, constant, and decreasing cost industries and the slope of the long-run supply curve. 2. Operating Efficiency, which is broader than production efficiency. 3. How the market economy solves the incentive and information problems – “The Invisible Hand”. So what can go wrong? Market Failure - The failure of private decisions in the marketplace to achieve an efficient allocation of scarce resources. In other words, we are making too much or too little of something because of a failure to properly take account of its benefits and costs. What markets does the government heavily regulate in the U.S. economy? Externalities – an action taken by a person or firm that imposes benefits or costs outside of any market exchange. We’ve seen these pictures earlier this semester, but we didn’t have a name for what they were yet. Now we do. So what to do? We have seen one solution, which is government regulation of the industry. There is another, which is to charge, or tax, people for the harm they are doing to others. This will “internalize the externality. Here is our factory causing $100,000 worth of harm to the people around the factory. It could cut the pollution in half by spending $25,000 on scrubbers. Will the owner do it? What if he had to pay $1 in taxes for each $1 harm done by his pollution? Some people have proposed a “carbon tax” as part of the solution to global warming. Besides externalities, there is another type of marked failure is known as public goods. Public Goods A good for which the cost of exclusion is prohibitive and for which the marginal cost of an additional user is zero. For example, a streetlight placed on a block. Examples of Public Goods 1) Streetlights 2) Roads 3) National Defense 4) Light Houses 5) Free Television The Free Rider Problem Free Riders – People or firms that consume a public good without paying for it. The government gets around the problem by not asking you to pay, but telling you to pay. In theory, the government can handle this problem. In practice, we still have our old problems of: 1) information. 2) incentive. Tragedy of the Commons - What happens when property rights are not assigned? Once property rights are assigned, problem solved. This is why the cow population is thriving and whales are hunted almost to extinction. The air is a commons. Unless the government enforces regulation or taxes. Of course, we have talked about air pollution before, under externalities. The tragedy of the commons isn’t really a new thing, it is a subset of externalities. Who owns the air? What we learned today. 1. The main types of market failure – Externalities, public goods, and the tragedy of the commons. 2. How the government can deal with these problems – regulation and taxes. Welcome to Day 18 Principles of Microeconomics What we learned yesterday. 1. The main types of market failure – Externalities, public goods, and the tragedy of the commons. 2. How the government can deal with these problems – regulation and taxes. Test Prep Day Welcome to Day 19 Principles of Microeconomics Test Day