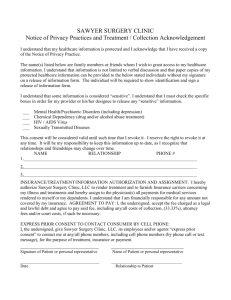

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer

advertisement