10_202_antigone_unit overview1415

advertisement

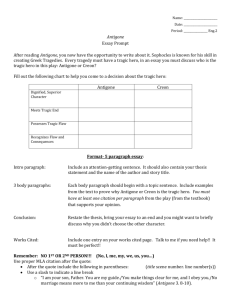

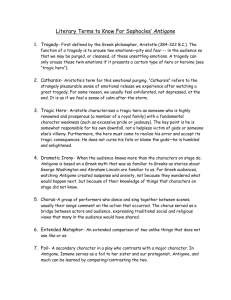

1 Document1 Antigone Unit Overview Who is the more tragic figure – Antigone or Creon? What absolute value systems are in conflict here, and where can we find this conflict today? What can we learn from Greek tragedy? Figure 1: Antigone by Frederick Leighton, 1882 Context (from “Greece and the Theater” in The Three Theban Plays, trans. Fagles) Written by Sophocles around 441 B.C.E. Sophocles is credited with writing 123 plays, only 7 of which have survived The Three Theban Plays in chronological order of when Sophocles wrote them are Antigone Oedipus the King Oedipus at Colonus In terms of the story itself (the Theban saga), Antigone is last. Schedule You will read the various sections of the play in class – aloud – with reading groups. Use the family tree (at the back of the packet) and textual notes (pages 395-405) to aid comprehension. In addition to reading a part each day, every person must take notes on the study questions. I will collect these notes and grade them for completion. 1 2 3 4 5 6 C-Block Sarah A. Margaret Aviva Eleanor Sam Zach Lily Julie Ksenia Sarah K. Henry Niamh Morgan Sasha Jacob D-Block Aidan Katie Kiki Kaitlin Cassandra Allison Katherine Suzie Yuval Jasmine Thomas Noah Maya Mitsuru Pete Danny Grace Emily Kiana Allie Lines Roles 1-179 180-426 427-704 705-1089 Antigone, Ismene, Chorus Creon, Leader, Sentry, Chorus Sentry, Creon, Antigone, Leader, Chorus, Ismene Creon, Haemon, Leader, Chorus, Antigone Anna Sophia Sarah F. 2 Document1 1090-end Directions: Tiresias, Creon, Leader, Chorus, Messenger, Eurydice, Study Questions Everyone in your group should answer the questions below. Bullet points are fine; messiness and a lack of textual evidence are not. Antigone Lines 1-179: Antigone makes her plans to disobey Creon. 1. Look back at what Antigone talks about on the first few pages. She is clearly concerned about honoring her family. What are two or three other things that she seems to be concerned with? What do these values reveal about her? 2. What does Antigone’s treatment of Ismene reveal about her personality? 3. How do Antigone and Ismene settle their differences? 4. Compare the way that Antigone feels about Polynices (32-36) with the Chorus’ description (125-131). How are we supposed to reconcile the discrepancy? Document1 3 Antigone Lines 180-426: Creon learns someone buried Polynices despite his decree. 1. Make a list of two or three of the values Creon advocates in his first speech. What do you think of each? Is it thoughtful? Is it a good position for a leader to take? 2. What do Creon’s interactions with the Leader (of the Chorus) and the Sentry reveal about his priorities and/or personality? 3. After rereading the “Ode to Man” from the Chorus (376-424), consider why they would start talking about man’s mastery of nature as well as his limitations. 4. Considering all that happens in this section, how would you describe the overall health of the city-state? Does this make you more or less sympathetic to what Antigone is trying to do? Document1 Antigone Lines 427-704: Creon confronts Antigone about her actions. 1. How would you describe Creon’s initial reaction to seeing Antigone brought before him? 2. Reread Antigone’s speech from 499-520. How does she justify her behavior? Is this a sensible argument? 3. Why might Ismene have changed her mind? List as many reasons as you can. 4. Why doesn’t Antigone accept this? 5. Make a series of stage directions for 625-645. What is each character doing while these lines are spoken? 4 Document1 5 Antigone Lines 705-1089: Creon’s son, Haemon, attempts to dissuade him from executing Antigone, but he is unsuccessful, so Antigone prepares to die. 1. To what does Haemon appeal in his attempt to save Antigone? 2. Why does Creon choose the particular method of execution that he does (870-8)? What does it say about him? 3. The ancient Greeks had two words for "love"; philia, meaning something like "friendship", and eros, which has more to do with passion. When the chorus talks about "love" in the ode, which of the two do they mean? And why is the chorus generalizing about love here? 4. How would you characterize the chorus' exchange with Antigone before she is sent to die? 5. Consider Antigone's speech, which begins at line 978. Is this speech consistent with what she has argued before? (When Creon bluntly accuses Polynices of betraying Thebes, what is Antigone’s response?) Document1 6 Antigone Lines 1090-end: It’s a Greek tragedy, so the ending is, well, tragic. 1. Decide to what extent Sophocles would agree, disagree, or amend the following statement: a stubborn adherence to personal conscience is the best way to achieve justice in the world. Support your reasoning with evidence. 2. Is Creon a successful leader? 3. In his 1955 essay “On the Future of Tragedy,” Albert Camus writes, “Antigone is right, but Creon is not wrong.” Explain how this is true. Document1 7 The Nature of Greek Tragedy Aristotle's ideas 1 about the structure, purpose, and intended effect of tragedy were recorded in his book of literary theory titled Poetics. His ideas have been adopted, disputed, expanded, and discussed for several centuries now. Here is a summary: 1. The tragic hero is a character of noble stature and has greatness. This should be readily evident. The character must occupy a "high" status position but must ALSO embody nobility and virtue as part of his/her innate character. 2. Though the tragic hero is pre-eminently great, he/she is not perfect. Otherwise, the rest of us--mere mortals--would be unable to identify with the tragic hero. We should see in him or her someone who is essentially like us, although perhaps elevated to a higher position in society. 3. The hero's downfall, therefore, is partially her/his own fault, the result of free choice, not of accident or villainy or some overriding, malignant fate. In fact, the tragedy is usually triggered by some error of judgment or some character flaw that contributes to the hero's lack of perfection noted above. This error of judgment or character flaw is known as hamartia and is usually translated as "tragic flaw" (although some scholars argue that this is a mistranslation). Often the character's hamartia involves hubris (which is defined as a sort of arrogant pride or over-confidence). 4. The hero's misfortune is not wholly deserved. The punishment exceeds the crime. 5. The fall is not pure loss. There is some increase in awareness, some gain in selfknowledge, some discovery on the part of the tragic hero. 6. Though it arouses solemn emotion, tragedy does not leave its audience in a state of depression. Aristotle argues that one function of tragedy is to arouse the "unhealthy" emotions of pity and fear and through a catharsis (which comes from watching the tragic hero's terrible fate) cleanse us of those emotions. It might be worth noting here that Greek drama was not considered "entertainment," pure and simple; it had a communal function--to contribute to the good health of the community. This is why dramatic performances were a part of religious festivals and community celebrations. 1 With thanks to Mr. Norton for his summary Document1 8