Writing about Syntax - River Dell Regional School District

advertisement

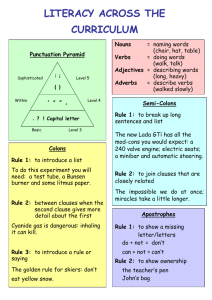

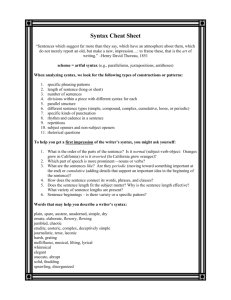

Writing about Syntax Writing About Syntax To say “the writer uses syntax to convey meaning” is a meaningless statement. You do not need to modify the word syntax as you do the word diction. For example you must say “religious diction” or “charged diction” but to say “interesting syntax” says nothing. When you comment on syntax, it is often not going to take up a whole paragraph. In fact you may not even use the word syntax. Your discussion of syntax needs to be related to how the writer executes a sentence to convey meaning or place emphasis, or create voice or tone. The basic order of sentences The order of the English sentence is for the most part prescribed. There must be a subject and verb Word order cannot be random ex: store went the to lady the. How Writers Manipulate Sentences How writers control and manipulate the sentence is a strong determiner of voice and imparts personality to the writing. Syntax encompasses word order, sentence length, sentence focus, and punctuation. Word Order Most sentences follow the subject-verbobject/complement pattern He was carrying a large suitcase. He gave us his permission. Word Order Subject-Verb Complement Pattern They elected Mary chairwoman. You made her angry. New York is our largest city. This book is dull. Changing Normal Word Order Authors shift between conformity and nonconformity, preventing reader complacency without using unusual sentence structure to the point of distraction. This is not to say that we write, “He changed the word order to wake us up” !!!! Examples Inverting subject and verb I am happy to see you. VS. Am I ever happy to see you! Placing a complement at the beginning of a sentence: He is without a doubt hungry VS. Hungry, without a doubt, he is. Placing an object in front of a verb I like Sara but not Penelope VS. Sara I like – not Penelope. Ode to Pizza I ate the best pepperoni pizza last night. The pizza was nice and hot when I opened the box. Each slice had a lot of cheese. The crust was chewy and fresh. It was delicious! Sentence Length Writers vary sentence length to forestall boredom and control emphasis. A short sentence following a much longer sentence shifts the reader’s attention, which emphasizes the meaning and importance of the short sentence. Works from different historical periods might do the opposite. “The Fanatics” – Eric Hoffer When the moment is ripe, only the fanatic can hatch a genuine mass movement. Without him the disaffection engendered by militant men of words remains undirected and can vent itself only in pointless and easily suppressed disorders. Without him, the initiated reforms, even when drastic, leave the old way of life unchanged, and any change in government usually amounts to no more than a transfer of power from one set of men of action to another. Without him there can perhaps be no new beginning. You try it… Of all the instruments of modern technology, only the computer brings people closer together. Add two long sentences which amplify the first sentence. Add one final short sentence to emphasize the first sentence. Examples In Bradbury’s description of the fire, his syntax changes from the short, robotic sounding sentences that indicate order to long, racing sentences that reflect the panic of the house as it is engulfed by fire. Clearly technology cannot perfectly control the world. * STYLE/FORM = CONVEY MEANING/IDEA Sentence Focus Sentence focus deals with variation and emphasis among sentences. Main ideas are usually in the main clause positions. Main clause placement may vary according to the type of tension the writer wants to create. Periodic Sentences Writers create syntactic tension by withholding syntactic closure until the end of the sentence. “As long as we ignore our children and refuse to dedicate the necessary time and money to their care, we will fail to solve the problem of school violence.” Example Darwin uses periodic sentence structure as he carefully approaches his hostile audience. Just as he presents his evidence before he declares his thesis, he places modifiers in each sentence before declaring his main points. Loose/Cumulative Sentences Sentences that reach syntactical closure early relieve tension and allow the reader to explore the rest of the sentence without urgency. “We will fail to solve the problem of school violence as long as we ignore our children and refuse to dedicate the necessary time and money to their care.” Does feeling or meaning change? Periodic: “As long as we ignore our children and refuse to dedicate the necessary time and money to their care, we will fail to solve the problem of school violence.” Loose: “We will fail to solve the problem of school violence as long as we ignore our children and refuse to dedicate the necessary time and money to their care.” Repetition Repetition is another way that writers achieve sentence focus. Purposeful repetition of a word, phrase, or clause emphasizes the repeated structure and focuses the reader’s attention to its meaning. Repetition of word, structure, anaphora Punctuation Punctuation is used to reinforce meaning, construct effect, and express the writer’s voice. Of particular interest in shaping voice are the semicolon, colon, and dash. PUNCTUATION MATTERS A woman without her man is nothing. A woman, without her man, is nothing. A woman: without her, man is nothing. ;;;;;; semicolon ;;;;;; The semicolon gives equal weight to two or more independent clauses in a sentence. The resulting balance reinforces parallel ideas and imparts equal importance to both (or all) of the clauses. ::::: colons ::::: Colons direct the reader’s attention to the words that follow. They can also be used between independent clauses if the second summarizes or explains the first. ---- dash ---A dash marks a sudden change in thought or tone, sets off a brief summary, or sets off a parenthetical part of the sentence. The dash often conveys a casual tone. Types of Sentences Simple Complex Compound Compound Complex Simple One independent clause and no subordinate clause. Great literature stirs the imagination. Complex One independent clause and at least one subordinate clause. Great literature, which stirs the imagination, also challenges the intellect. Compound Two or more independent clauses but no subordinate clauses. Great literature stirs the imagination; moreover, it challenges the intellect. Compound Complex Sentences Contains two or more independent clauses and at least one subordinate clause. Great literature, which challenges the intellect, is sometimes difficult, but it is also rewarding. Sentences Classified by Purpose There are four kinds of sentence: Declarative Imperative Interrogative Exclamatory Declarative Makes a statement Homes should be made safer for the elderly. Imperative Gives a command or makes a request Close that book and pay attention. Interrogative Asks a question What was the name of that song? Exclamatory Expresses strong feeling How happy I am to know that you will all pass this AP exam! Terms to Describe Syntax Asyndeton A writing style that omits conjunctions between words, phrases, or clauses Asyndeton adds speed and rhythm to the words. It leaves an impression that the list is not complete and adds drama Example: Compare: “I play hockey, baseball and football.” vs. “I play hockey, baseball, football.” Compare: She’s a genius and a star. with She’s a genius, a star. Polysyndeton The repetition of conjunctions such as “and”, “or”, “for” and “but” in close succession, especially when most of them could be replaced with a comma. The repetition of the conjunctions adds power to the other words. Polysyndeton slows down the pace of the sentence. It can add rhythm and cadence to a sentence or series of sentences. There is a feeling that the ideas are being built up. Compare: “He is brave and honest and good and decent.” vs. “He is brave, honest, good and decent.” Antimetabole Repetition of the same words or phrases in reverse order. The focus of the second clause is different from the focus in the first clause because of the reversed word order. The reversal of words is often unexpected and thought-provoking, getting the audience to consider things from a different angle. The key message is usually in the second clause or sentence. Antimetabole is frequently used to motivate the audience. Examples: “One for all and all for one!” “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” — Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr Epistrophe Repetition of a word or phrase at the end of successive sentences or clauses. Effect: Because the emphasis is on the last word(s) of a series of sentences or phrases, epistrophe can be very dramatic. It is particularly effective when one wishes to emphasize a concept, idea or situation. Note, for example, the concepts emphasized in the quotes below: people; problems; moments; domination; togetherness; ability. Repetition makes the lines memorable. The speaker’s words have rhythm and cadence. Epistrophe is the opposite of anaphora As is the case with anaphora, speakers should be careful not to overuse epistrophe. Epistrophe is effective even when the words differ slightly; for example, when they are singular and plural as in the quote from Bill Gates below. Americans have responded with a simple creed that sums up the spirit of a people: Yes we can. It was a creed written into the founding documents that declared the destiny of a nation: Yes we can. It was whispered by slaves and abolitionists as they blazed a trail toward freedom through the darkest of nights: Yes we can. It was sung by immigrants as they struck out from distant shores and pioneers who pushed westward against an unforgiving wilderness: Yes we can.“ — Barack Obama, New Hampshire primary, 8 January 2008 “Market forces cannot educate us or equip us for this world of rapid technological and economic change. We must do it together. We cannot buy our way to a safe society. We must work for it together. We cannot purchase an option on whether we grow old. We must plan for it together. We can’t protect the ordinary against the abuse of power by leaving them to it; we must protect each other. That is our insight. A belief in society. Working together.” — Tony Blair, Blackpool, 4 October 1994 “I left campus knowing little about the millions of young people cheated out of educational opportunities here in this country. And I knew nothing about the millions of people living in unspeakable poverty and disease in developing countries.” — Bill Gates, Harvard University address, 7 June 2007 Anaphora Repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive sentences or clauses. Effect: *Key words or ideas are emphasized, often with great emotional pull. *Repetition makes the line memorable. *The speaker’s words have rhythm and cadence. “We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills …” — Winston Churchill, House of Commons, London, England, 4 June 1940 Zeugma The use of a word to modify or govern two or more words when it is appropriate to only one of them or is appropriate to each but in a different way. Creates verbal puns, humor and wordplay. Examples: to wage war and peace On his fishing trip, he caught three trout and a cold. “Mr. Jones took his coat and his leave”

![The Word-MES Strategy[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007764564_2-5130a463adfad55f224dc5c23cc6556c-300x300.png)