Administrative Law

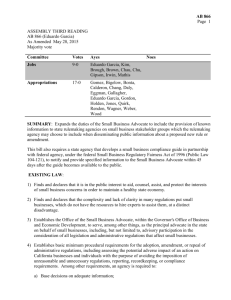

advertisement