Passages from Moby-Dick

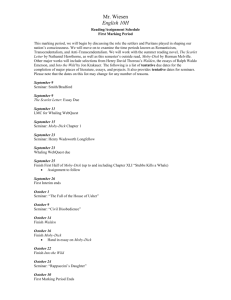

advertisement