gk - WordPress.com

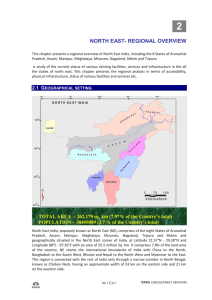

advertisement