Commonwealth v. Frye, Brief for the Commonwealth

advertisement

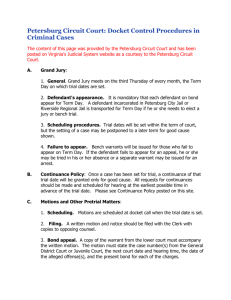

2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 1 For Dockets See 2013-P-0434 Appeals Court Of Massachusetts. COMMONWEALTH, Appellee, v. Donald FRYE, Appellant. No. 2013-P-434. August, 2013. On Appeal from a Judgment of the District Court Department Brief for the Commonwealth For the Commonwealth:, Jonathan W. Blodgett, District Attorney, For the Eastern District.David F. O'Sullivan, Assistant District Attorney, Ten Federal Street, Salem, Massachusetts 01970, (978) 745-6610, BBO No. 659068, david.o'sullivan @state.ma.us. *i TABLE OF CONTENTS Issues Presented ... 1 Statement of the Case ... 2 Statement of the Facts ... 3 Argument I. The trial judge created no risk of a miscarriage of justice by permitting a defense witness to invoke the Fifth Amendment privilege where the witness had not waived the privilege through her prior testimony, and this did not deprive the defendant of his right to present a defense. ... 10 II. The trial judge created no risk of a miscarriage of justice where, when the defendant claimed not to understand the judge's twelfth admonishment to him to respond to questions rather than offer narrative testimony, the judge said, “Yes, you do, sir. You're very intelligent, as you have already told us, and wait for your lawyer's questions.” ... 16 III. The trial judge properly instructed that assault and battery may be committed by acts creating a “potential” rather than a “likelihood” of physical harm and, assuming an error, there was no risk of a miscarriage of justice where the © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 2 evidence showed the defendant punched and broke the victim's nose and he claimed he acted in self-defense. ... 22 IV. The defendant has not met his burden to show an actual conflict of interest from the fact that his counsel, in his prior job as an *ii assistant district attorney, prosecuted a defense witness, where the defendant offered only unsupported speculation that the witness “may well have harbored hostility toward” defense counsel. ... 24 29 V. The defendant had no standing to assert any social worker/client privilege that a defense witness may have possessed where the witness himself did not assert the privilege. Conclusion ... 32 Addendum ... 33 Rule 16(k) Certification *iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Commonwealth v. Bonefont, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 54 (1993) ... 25, 28, 29 Commonwealth v. Burke, 390 Mass. 480 (1983) ... 23 Commonwealth v. Carney, 31 Mass. App. Ct. 250 (1991) ... 16 Commonwealth v. Casiano, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 705 (2007) ... 14 Commonwealth v. Connor, 381 Mass. 500 (1980) ... 28 Commmonwealth v. Croken, 432 Mass. 266 (2000) ... 26, 27 Commonwealth v. Dargon, 457 Mass. 387 (2010) ... 11 Commonwealth v. Davis, 376 Mass. 777 (1978) ... 25 Commonwealth v. Denham, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 724 (1979) ... 29 Commonwealth v. Dixon, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 653 (1993) ... 23 Commonwealth v. Errington, 390 Mass. 875 (1984) ... 22 © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Commonwealth v. Filippidakis, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 679 (1991) ... 28 Commonwealth v. Fitzgerald, 380 Mass. 840 (1980) ... 16 Commonwealth v. Funches, 379 Mass. 283 (1979) ... 12, 13, 14 Commonwealth v. Greco, 76 Mass. App. Ct. 296 (2010) ... 24 *iv Commonwealth v. Gomes, 54 Mass. App. Ct. 1 (2002) ... 16 Commonwealth v. Gonzalez, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 913 (1986) ... 19 Commonwealth v. Haley, 363 Mass. 513 (1973) ... 20 Commonwealth v. Helfant, 398 Mass. 214 (1982) ... 22 Commonwealth v. Judge, 420 Mass. 433 (1995) ... 12 Commonwealth v King, 436 Mass. 252 (2002) ... 11, 13 Commonwealth v. Leach, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 758 (2009) ... 21 Commonwealth v. Lee, 394 Mass. 209 (1985) ... 27 Commonwealth v. Martin, 423 Mass. 496 (1996) ... 12 Commonwealth v. McCoy, 456 Mass. 838 (2010) ... 11 Commonwealth v. Medina, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2011) ... 23 Commonwealth v. Miller, 435 Mass. 274 (2001) ... 27 Commonwealth v. Oliveria, 438 Mass. 325 (2002) ... 31, 32 Commonwealth v. Paradise, 405 Mass. 141 (1989) ... 16 Commonwealth v. Pelosi, 441 Mass. 257 (2004) ... 31 © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. Page 3 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Commonwealth v. Penta, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 36 (1992) S.C., 423 Mass. 546 (1996) ... 12 *v Commonwealth v. Randolph, 438 Mass. 290 (2002) ... 11, 15 Commonwealth v. Saferian, 366 Mass. 89 (1974) ... 27 Commonwealth v. Shraiar, 397 Mass. 16 (1986) ... 26 Commonwealth v. Shippee, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 569 (2013) ... 16 Commonwealth v. Sneed, 376 Mass. 867 (1978) ... 20 Commonwealth v. Stote, 456 Mass. 213 (2010) ... 26, 27 Commonwealth v. Sylvester, 388 Mass. 749 (1983) ... 21 Commonwealth v. Turner, 371 Mass. 803 (1977) ... 11, 19 Commonwealth v. Walter, 396 Mass. 549 (1986) ... 26 Commonwealth v. Watkins, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 69 (2005) ... 16 Commonwealth v. Winburn, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 1111 (2010) ... 23 Commonwealth v. Woody, 429 Mass. 95 (1999) ... 19 Liteky v. United States, 510 U.S. 540 (1994) ... 20 McCarthy v. Arndstein, 262 U.S. 355 (1923) ... 12 Quercia v. United States, 289 U.S. 466 (1933) ... 21 Smith v. United States, 337 U.S. 137 (1949) ... 12 *vi Taylor v. Commonwealth, 369 Mass. 183 (1975) ... 11 Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 112, Section 135B ... 30 © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. Page 4 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 5 Chapter 268, Section 13B ... 13 Chapter 256, Section 120 ... 13 Massachusetts Rules of Appellate Procedure Rule 8 ... 19 Other Authorities Criminal Model Jury Instructions for Use in the District Court, Inst. 6.140 (MCLE 2009 ed) ... 23 M. Brodin and M. Avery, Handbook of Massachusetts Evidence, § 5.14.7 (8th Ed. 2007) ... 13 *1 ISSUES PRESENTED I. Whether the trial judge created a substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice by permitting a defense witness to invoke the Fifth Amendment privilege where the witness had not waived the privilege and this did not deprive the defendant of his right to present a defense. II. Whether the trial judge created a risk of a miscarriage of justice where, when the defendant claimed not to understand the judge's twelfth admonishment to him to respond to questions rather than offer narrative testimony, the judge said, “Yes, you do, sir. You're very intelligent, as you have already told us, and wait for your lawyer's questions.” III. Whether the trial judge properly instructed that assault and battery may be committed by acts creating a “potential” rather than a “likelihood” of physical harm and whether, assuming an error, there was a risk of a miscarriage of justice where the evidence showed the defendant punched and broke the victim's nose and he claimed he acted in self-defense. IV. Whether the defendant met his burden to show an actual conflict of interest from the fact that his counsel, in his prior job as an assistant district attorney, prosecuted a defense witness, where the defendant offered only unsupported speculation that the witness “may well have harbored hostility toward” defense counsel. V. Whether the defendant had standing to assert any social worker/client privilege that a defense witness may have possessed where the witness himself did not assert the privilege. *2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE[FN1] FN1. References: Dangerousness hearing transcript (58A/page); Trial transcript (Tr. I-II/page); Record ap- © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 6 pendix (R. page). The transcript of the August 30, 2012 hearing in which the defendant proffered and then withdrew a guilty plea is not cited. On July 27, 2012, a complaint issued in Lynn District Court charging the defendant, Donald Frye, with an assault and battery on Angela Russell (“the victim”) (G.L. c. 265, § 13A(a)) (No. 1213CR3590) (R. 1, 2). On August 1, 2012, the Court (Fortes-White, J.,) held an evidentiary hearing on the Commonwealth's petition to hold the defendant as dangerous pursuant to G.L. c. 276, § 58A (“the 58A hearing”); the victim and three defense witnesses (Tremayne Ellison, Donna Hiltz, and the defendant) testified (R. 4). The judge found the defendant dangerous and ordered him held for ninety days (R. 4). On October 11 and 12, 2012, the defendant was tried before a jury (Flately, J. presiding) and found guilty (R. 3).[FN2] The Court sentenced him to a 21/2 year house of correction term, with 18 months to be served and the balance suspended until October 14, 2015, with conditions including completion of the Batterer's *3 Intervention Program (R. 3; Tr. 11/264). He timely appealed (R. 7) and the case was entered in this Court on March 13, 2013. FN2. The defendant was represented by the same counsel at the 58A hearing and trial. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS I. The crime: The defendant repeatedly punches the victim in the face, breaking her nose The victim and defendant were girlfriend and boyfriend and lived together at the victim's house in Lynn from June through December, 2011 and again from May through July, 2012 (Tr. 1/74-75). On July 27, 2012, around 10:30 or 11:00 P.M., the victim was home alone watching “Everybody Loves Raymond” on TV, when the defendant and Tremayne Ellison arrived (Tr. 1/76-78). The defendant was a “CSP worker,”[FN3] a job that involved helping clients “achieve [their] goals” and Ellison was the defendant's client (Tr. 1/77). The defendant and Ellison were drinking; the defendant had a “tall can of beer” and Ellison had a “big bottle []” (Tr. 1/78). The defendant was on his cell phone, arguing with someone (Id.). The victim was focused on the TV did not pay attention to the argument (Id.). FN3. It is unclear from the record what the acronym stands for. She told the defendant she wanted him to leave; he called her into the bathroom and said “‘Well, if *4 you're going to kick me out of the house for the night, I need something to survive on the street”’ (Tr. 1/78- 80). He asked her for $100, then $60 (Id.). She did not want to give him money, but finally agreed to give him $40, which she took from her pocketbook and threw at him, “disgusted” (Id.). He and Ellison left (Tr. 1/81). An hour later, the defendant called the victim; he was “very curt” and “forceful” and told her to pick him up at the Stop and Shop in Lynn (Tr. 1/81-83). At first, she refused but then agreed because she was “scared” and “didn't want anything to happen to him” (Tr. 1/82-83). She arrived there to find him “screaming” into his cell phone; a security guard there was “just staring at him” (Tr. 1/82). He got into the victim's car and said, “Drive to Essex Street” (Tr. 1/83), which was where his ex-girlfriend, Donna Hiltz, lived; he had “see[n]” Hiltz during a period when the victim and © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 7 defendant were separated (Tr. 1/83). Hiltz' car had run out of gas; the victim stopped behind it and the defendant got out and pushed Hiltz' car to the side of the road, then got back in the victim's car and said, “All right let's go” (Tr. 1/83-84). He then answered a call on his cell phone, *5 yelled into the phone, and hung up (Tr. 1/84). The victim asked, “‘What's going on,”’ and the defendant said, “‘Shut the fuck up”’ or “‘Mind your fucking business”’ and “‘Just drive to Hanover Street”’ (Id.). She drove there and, at his command, stopped the car near a “Spanish store” and shut off the car (Tr. 1/84-85). He left the car, then re-entered and made a phone call in which he said, “‘She's not there”’ (Tr. 1/85-86). He again left the car and returned, this time “mad” and “screaming” into his phone, “‘She's not there,”’ “‘Bring it to me”’ and “‘Tremayne, don't fuck around”’ (Tr. 1/86). The victim took her cell phone from her purse -- she had a “nervous habit” of checking it (Tr. 1/86-87). The defendant grabbed it from her; the victim said, “‘Give me my phone, give me my phone,” and wrested it back from the defendant (Id.). The defendant, still on his phone, slapped her on the chin (Id.). She said, “Don't slap me” and “pushed where he had the cell phone” (Tr. 1/88). The defendant, still on his phone, punched the victim three or four times in the face with his right hand (Tr. 1/89). The victim felt something warm coming from her face; it was blood (Id.). She said, “‘That's nice”’ and told him to get out of the car (Id.). The *6 defendant did so and the victim drove home and called the Lynn Police (Tr. 1/90). Officer Albert DiVirgilio responded and found the victim with blood coming from both nostrils; she was upset and appeared to have been crying (Tr. 1/129). The officer summoned an ambulance, which arrived and transported her to Union Hospital, where she was diagnosed with a fractured nose (Tr. 1/92-93, 130). Photographs taken several days later were admitted, showing bruising about the victim's eyes and her still-swollen nose (Tr. 1/93). The victim testified to several prior instances in which the defendant was violent or verbally abusive toward her, including grabbing her throat in August and October of 2011 (Tr. 1/94-96). He also threatened her in October and November 2011, saying, “I feel like slicing your fucking throat,” and, when she was putting on her shoes, “‘I feel like kicking your fucking teeth down your throat”’ (Tr. 1/97). II. The trial A. The Commonwealth's case The Commonwealth's case was presented as summarized above through the testimony of the victim and Officer DiVirgilio. *7 B. The defense The defendant claimed he acted in self-defense after the victim, in a jealous rage over the defendant's relationship with Hiltz, attacked him (Tr. 1/72-73; Tr. 11/225). On cross-examination, the victim admitted that, a few days before the incident, she called Hiltz and “threatened to get [the defendant] into trouble” (Tr. 1/109). The victim explained that she had meant she was going to get the defendant in trouble with his job for dating Hiltz because she was a former client of his (Tr. 11/109, 122, 125). © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 8 The defense called two witnesses, Ellison and the defendant. Ellison contended that, after he arrived with the defendant at the victim's house, the victim, enraged that the defendant had lent out a car rented under her insurance, and jealous of Hiltz, beat the defendant and threatened to kill him with a kitchen knife (Tr. 1/141-146). The defendant claimed that, while in the car on Hanover Street, he was “trying to talk about the rental car” when the victim, jealous of Hiltz, began striking him and then reached into her purse (Tr. 11/203-204). Believing she was pulling out a “butcher knife,” he hit her twice (Tr. 11/204-205). *8 III. Hiltz' invocation of the Fifth Amendment A. Hiltz' testimony at the 58A hearing At the 58A hearing, Hiltz testified that the victim was jealous of Hiltz and, a few days before the charged incident, had left Hiltz a voicemail message in which the victim said, “I'm going to get him [the defendant] in trouble” (58A/73-75, 78).[FN4] She also testified that the victim told Hiltz after the incident “that she [the victim] threw a few punches at him too” and “got a good whack into him” (58A, 76-77). FN4. At the same hearing, the victim admitted leaving the message and stated that she meant she was going to get him in trouble “with his work” (58A/27, 41), as she did at trial, see supra. at p. 7. On cross-examination, the prosecutor asked Hiltz, “And you spoke to [the victim] today in the courthouse, right?”; Hiltz responded, “Yeah. I said hi, yeah” (58A/78). Hiltz was not asked any more questions about this conversation or its content. B. Hiltz invokes the Fifth at trial On the first day of trial, the prosecutor alerted the judge that Ellison and Hiltz, two persons on the defense witness list, had possible Fifth Amendment privileges, because they had approached the victim before the 58A hearing and asked her to drop the *9 charge (Tr. 1/18-19).[FN5] Defense counsel responded that he had not been informed of or seen a report pertaining to the allegation and did not represent Hiltz and Ellison (Tr. 1/19). The judge told Hiltz, “It's been represented that you made attempts to try to get the case against [the defendant] dropped, and if true, that could be considered as interfering with a witness, intimidation of a witness, and that's a crime,” she may be asked questions concerning this at a trial, and her answers may incriminate her (Tr. 1/31-33). The judge offered to appoint an attorney to consult with her about a possible invocation of her Fifth Amendment privilege (Id.). Hiltz stated, “But that was brought up last time I testified [at the 58A hearing], that I talked to her, and that was brought up” (Tr. 1/33). The judge stated that she had a “separate right not to give evidence in this case” (Tr. 1/33). Hiltz requested and was appointed a lawyer and, after consultation, invoked her Fifth *10 Amendment privilege not to testify (Tr. 1/33, 44-45). The defendant did not object.[FN6] FN5. The victim testified at the 58A hearing that Hiltz and Ellison had approached her before the hearing and said, “He [the defendant] spent 15 years in jail, he doesn't need to spend any more time. Think about his job. © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 9 He's helped so many people” (Tr. 58A/22). (The defendant pled guilty to manslaughter in 1997 and served a lengthy sentence; these facts were not admitted at trial (Tr. 1/20-22, 25; Tr. 11/262)). FN6. Ellison declined to consult with an attorney and, as noted, testified at trial (Tr. 1/37). Additional facts are set forth in the pertinent argument section. ARGUMENT I. The trial judge created no risk of a miscarriage of justice by permitting a defense witness to invoke the Fifth Amendment privilege where the witness had not waived the privilege through her prior testimony, and this did not deprive the defendant of his right to present a defense. [FN7] FN7. Addressing the defendant's claims I and IV. The defendant claims that Hiltz waived her Fifth Amendment privilege by testifying at the 58A hearing that she had “said hi” (58A/78) to the victim before the hearing. He says that permitting Hiltz to invoke the privilege at trial was error that deprived him of his right to present a defense. D.Br. 17-22. The claim is not preserved by an objection below (Tr. 1/44-45) and is therefore reviewed to determine only whether any error created a substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice.[FN8] There was no error, and no such risk. FN8. Under that standard, this Court “‘review[s] the evidence and case as a whole and ask four questions: ‘(1) Was there error? (2) Was the defendant prejudiced by the error? (3) Considering the error in the context of the entire trial, would it be reasonable to conclude that the error materially influenced the verdict? (4) May we infer from the record that counsel's failure to object or raise a claim of error at an earlier date was not a reasonable tactical decision?”’ Commonwealth v. Dargon, 457 Mass. 387, 398 (2010) quoting Commonwealth v. McCoy, 456 Mass. 838, 850 (2010), Commonwealth v. Randolph, 438 Mass. 290, 298 (2002). “Relief under this standard is seldom granted, and may only be granted where the answer to all four above questions is, ‘Yes.”’ McCoy, 456 Mass. at 850, quoting Randolph, 438 Mass. at 297-298. FN9. This “waiver by testimony” rule has twin rationales: First, “‘when a witness has freely testified as to incriminating facts, continued testimony as to details would no longer tend to incriminate”’ Commonwealth v. King, 436 Mass. 252, 259 (2002), quoting Taylor v. Commonwealth, 369 Mass. 183, 190 (1975). Second, “allowing the testimony to remain in a witness-selected posture would result in serious, unjust distortion” and the witness “‘cannot be allowed to state such facts only as he pleases to state, and to withhold other facts.”’ Id., citation omitted. *11 “‘It has long been the law in Massachusetts that if an ordinary witness, not a party to a cause, voluntarily testifies to a fact of an incriminating nature he waives his privilege as to subsequent questions seeking related facts.” Commonwealth v. King, 436 Mass. 252, 259 (2002), quoting Taylor v. Commonwealth, 369 Mass. 183, 189 (1975).[FN9] But “[i]n view of the importance of the constitutional right against self-incrimination ... the Supreme Court has insisted © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 10 that waiver of that right ‘is not lightly to be inferred.”’ *12Commonwealth v. Turner, 371 Mass. 803, 810 (1977), quoting Smith v. United States, 337 U.S. 137, 150 (1949), further citations omitted.[FN10] FN10. “[T]he waiver by testimony rule applies only ‘to the proceeding in which [the testimony] is given and does not extend to subsequent proceedings.”’ Commonwealth v. Martin, 423 Mass. 496, 501 (1996) (waiver of privilege before grand jury does not waive privilege at trial). The Commonwealth assumes that the post-complaint 58A hearing constituted the same proceeding for purposes of this rule. See Commonwealth v. Judge, 420 Mass. 433, 445 n. 8 (1995) (hearing on suppression motion is same proceeding as trial for purposes of waiver by testimony). Commonwealth v. Penta, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 36, 45-46 (1992), S.C., 423 Mass. 546, (1996). “In order for a waiver by testimony to occur, the witness must admit to at least one element of a crime.” M. Brodin and M. Avery, Handbook of Massachusetts Evidence, § 5.14.7, p. 274 & n. 114 (8th ed. 2007), citing Commonwealth v. Funches, 379 Mass. 283, 291 (1979). See McCarthy v. Arndstein, 262 U.S. 355, 359 (1923) (“where the previous disclosure by an ordinary witness is not an actual admission of guilt or incriminating facts, he is not deprived of the privilege of stopping short in his testimony whenever it may fairly tend to incriminate him”). “Even where incriminating information is disclosed, however, there is no waiver as to further disclosures that pose ‘a real danger of legal detriment’ -- i.e., disclosure that would supply an additional link in the chain of *13 evidence.” M. Brodin and M. Avery, Handbook of Massachusetts Evidence, § 5.14.7, p. 274 & n. 114 (8th ed. 2007), quoting Funches, 379 Mass. at 290 & n. 8. That Hiltz said “‘Hi”’ to the victim before the 58A hearing, was not, without more, a “fact of an incriminating nature.” King, 436 Mass. at 259. Compare Funches, 379 Mass. at 291 (witness who testified that defendants went to his house and told him they wanted to buy heroin had not testified to a fact of an incriminating nature). Indeed, Hiltz did not even testify whether the victim had greeted her first. As such, Hiltz' 58A testimony did not suffice to prove an element of the crime of witness intimidation. See G.L. c. 268, § 13B, as amended through St.2010, c. 256, § 120 (elements: 1) “directly or indirectly, willfully” “threatens, or attempts or causes physical injury, emotional injury, economic injury or property damage to”; or “conveys a gift, offer or promise of anything of value to;” or “misleads, intimidates or harasses”; 2) “a witness or potential witness at any stage of a criminal investigation” [or other persons not pertinent here]; 3) “with the intent to impede, obstruct, delay, harm, punish or otherwise interfere thereby, or do so with *14 reckless disregard, with such a proceeding.”) Hiltz' “‘Hi”’ plainly did not convey a gift; was not a “threat[]” or an “offer or promise of anything of value; and was not “mislead [ing].” And without more, it did not constitute “intimidat[ion]”.[FN11] FN11. See and contrast Commonwealth v. Casiano, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 705 (2007) (defendant's act of pointing a cell phone at an undercover police officer waiting to testify against defendant and pressing buttons as if he were taking photographs constituted witness “intimidation” where the action threatened the officer's continuing safety); G.L. c. 268, § 13B(3) ( “‘harass' shall mean to engage in any act directed at a specific person or persons, which act seriously alarms or annoys such person or persons and would cause a reasonable person to suffer substantial emotional distress”). And even if Hiltz' 58A testimony was incriminating, answering further questions about the substance of the conver- © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 11 sation carried a further “real danger of legal detriment” by supplying “additional link[s] in the chain of evidence” against her. Funches, 379 Mass. at 290 & n. 8. She was entitled to invoke her still-intact privilege not to answer them. Id. In any event, even if the judge wrongly permitted Hiltz to claim the privilege, this did not deprive the defendant of his right to present a defense. At *15 trial, the victim admitted on cross-examination leaving the message as to which Hiltz would have testified (Tr. 1/109), and defense counsel twice featured the message in his closing argument (Tr. 11/223, 225). The defendant points to nothing in addition that Hiltz could have offered at trial regarding this message that would have made any difference. Further, both Ellison and the defendant testified to the victim's alleged jealousy of Hiltz (Tr. 1/140; Tr. 11/173, 179, 198, 211). Hiltz did not witness the charged act and, to the extent Hiltz' testimony about the victim's prior statements may have been relevant for impeachment, the victim admitted “push[ing]” the defendant “where he had the cell phone” (presumably, the face) before the defendant began punching her (Tr. 1/88). Thus, Hiltz' absence did not “materially influence the verdict,” Commonwealth v. Randolph, 438 Mass. 290, 298 (2002), or deprive him of his right to present a defense. In his Argument IV, the defendant relatedly claims that the prosecutor's failure to disclose that Hiltz had a potential Fifth Amendment privilege deprived him of the opportunity of arguing that it had been waived. D.Br. 33. Because the waiver argument *16 lacks merit for the reasons set forth above, the claim fails. Cf. Commonwealth v. Shippee, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 659, 668 (2013) (“The failure to pursue futile or improbable arguments at trial cannot constitute ineffective assistance.”). II. The trial judge created no risk of a miscarriage of justice where, when the defendant claimed not to understand the judge's twelfth admonishment to him to respond to questions rather than offer narrative testimony, the judge said, “Yes, you do, sir. You're very intelligent, as you have already told us, and wait for your lawyer's questions.” The defendant's unpreserved claim[FN12] that the judge expressed an opinion on the defendant's credibility, D.Br. 22-27, ignores the circumstances that prompted the judge's remarks. See Commonwealth v. Carney, 31 Mass. App. Ct. 250, 252 (1991) (claims to be judged “viewing the entire trial in context”; disapproving of *17 defendant's “[c]utting and pasting portions of the record to suit [his] argument”). FN12. The lack of an objection is not excused simply because the alleged error “concerns a judge's action.” D.Br. 24. It is true that “[i]n light of the delicate problem that objections to a judge's actions present to defense counsel, [our courts] do not weigh heavily against the defendant the absence of objections in each instance” of repetitive judicial conduct Commonwealth v. Fitzgerald, 380 Mass. 840, 849 (1980) (judicial questioning of witness). But “the total absence of any objection” is a different matter. Id. “[S]uch inaction by counsel is not justifiable, and will trigger only limited appellate review,” under the substantial-risk standard. Commonwealth v. Watkins, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 69, 73 (2005). See Commonwealth v. Gomes, 54 Mass. App. Ct. 1, 5 (2002); Commonwealth v. Paradise, 405 Mass. 141, 157 (1989). At trial, the defendant repeatedly strayed beyond the questions asked and tried to offer a narrative. Early in his testimony, defense counsel asked: © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 12 Q. Did you receive any type of training' with regard to [your employment as a community support worker]? A. Yes, I did, and I'd like to tell you something about (inaudible) -- THE COURT: Sir, no. You need to just focus on your lawyer's questions and wait for the next question, please (Tr. 11/170). Ignoring this instruction, the defendant continued to offer a narrative account. The judge politely repeated to him eleven times to respond only to the question asked (Tr. 11/171: “Sustained. It goes beyond the scope of the question. Wait for your lawyer's question, sir.”; Tr. 11/172: “Sustained. It goes beyond the scope of the question. Wait for your lawyer's question, sir.”; Tr. 11/174: “Sustained. It's going well beyond the scope of the question. Question and answer format, please, not narrative. Thank you.”; Tr. 11/175: “THE COURT: Sir, a yes is a complete answer. THE WITNESS: Oh. Yes. THE COURT: And you don't go beyond a yes or a no if it calls for *18 a yes or no answer. Next question, please.”; Tr. 11/175: “Sustained. It's beyond the scope of the question.”; Tr. 11/176: “Yes is a complete answer.”; Tr. 11/179: “Sustained. It's going beyond the scope of the question. Listen to the question, sir. Thank you.”; Tr. 11/181: “Sustained. It's beyond the scope of the question.”; Tr. 11/185: “All right. Question -answer format, please, not narrative.”; Tr. 11/186: “Sustained. It's nonresponsive. Question and answer format, please, not narrative.”; Tr. 11/186: “Sustained. Sir, you need to wait for the questions. Don't go beyond the question, and then wait for the next question. Thank you.”). The twelfth time the defendant attempted to give a narrative response, the following occurred: [Defense counsel]: What was your reaction to her hitting you? A. Basically, I'm so (inaudible) moved over to the side (inaudible). The first one got me (inaudible) because he had never seen her in that light. Q. Did you -A. It surprised me - [The Prosecutor]: Objection. THE COURT: All right. Sir, sir, I'm going to have to insist that you limit yourself to answering the questions and don't go beyond and volunteer information which is objectionable as not responsive to the question. Next question, please. *19 THE WITNESS: I don't understand. THE COURT: Yes, you do, sir. You're very intelligent, as you have already told us, [FN13] and wait for your lawyer's questions FN13. This remark references testimony by the defendant, that he was intelligent, which does not appear in the transcript, possibly because it was in one of the many inaudible portions of his testimony that he did not seek to reconstruct. See Mass. R. App. P. 8; Commonwealth v. Woody, 429 Mass. 95, 97-98 (1999); (appellant is obliged to ensure an adequate record for appellate review). In any event, he does not claim that he did not make this particular comment or that the judge's remark was not supported by the record. (Tr. II/ 187-188). Later, after again being instructed to “wait for the question” (Tr. 11/189), the defendant complained, “I'm not able to tell my story” (Tr. 11/190). The judge responded: “Sir, you can answer the questions that are put to you and listen to the question that your lawyer just asked you ... You may answer that question” (Tr. 11/190). [FN14] © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 13 FN14. See also Tr. 11/191, 193, 202, 212, 213, 218. “The judge was attempting to secure more responsive answers from the defendant, who was volunteering substantially more than each question called for.” Commonwealth v. Turner, 371 Mass. 803, 813 (1977) (judge's statement that testifying defendant was “inclined to make speeches” was “warranted” and “not error”). Commonwealth v. Gonzalez, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 913, 914 (1986) (judge‘s *20 attempts “to rein in [defense] witnesses who volunteered unresponsive answers” were not error; judge was “even-handed” and “not unkind or overbearing and sought repeatedly to explain to witnesses the confines imposed by the rules of evidence and courtroom decorum. We do not think his remarks reflected on the credibility of defense witnesses.”). To be sure, the judge's comment “savors of sarcasm,” Commonwealth v. Haley, 363 Mass. 513, 521 (1973), but such “expressions of impatience, dissatisfaction, annoyance, and even anger, [] are within the bounds of what imperfect men and women, even after having been confirmed as [] judges, sometimes display.” Liteky v. United States, 510 U.S. 540, 542, 556 (1994). Even if “stern and short-tempered,” “[a] judge's ordinary efforts at courtroom administration” including “admonishing witnesses to keep answers responsive to actual questions directed to material issues” are “routine trial administration efforts” and do not establish judicial bias or partiality. Id.[FN15] FN15. Commonwealth v. Sneed, 376 Mass. 867 (1978) is readily distinguishable. There, the judge “in many and diverse ways” deprived the defendant of a fair trial, and the Court discussed only the “most obvious illustrations” of this: 1) the judge “addressed indmissible questions to [defense witness] concerning her ‘failure’ to testify at prior District Court proceedings”; 2) emphasized this failure in the instructions, id. at 869; and 3) “admonished the witness as to perjury” at sidebar that the jurors might have heard. Id. “[T]he circumstances were such that the jury were probably aware that the judge did not believe the witness.” Id. “It is reasonable to assume, and almost inescapable that he unjustifiably intimidated the witness and severely eroded her credibility.” Id. at 870. Also contrast Commonwealth v. Sylvester, 388 Mass. 749,750-753(1983) (judge cut off an answer during direct examination of the defendant, saying: “I am not going to let you let him spill out narrative material here about self-serving statements about what he did in the police station. There is a way to try this case. Get to it.”); Quercia v. United States, 289 U.S. 466, 469 (1933) (judge told jurors that he believed defendant's testimony “was a lie”). *21 In the circumstances, the judge showed remarkable restraint and courteousness. As she plainly understood, the defendant's loquacity had the potential to hurt as well as help him. The absence of an objection suggests that defense counsel understood this, too, and did not view the judge's remark as expressing an opinion on the defendant's credibility. Rather, counsel likely saw it as a further, proper, effort to rein in the defendant, who, in a misguided effort to “tell his story,” may have offered testimony prejudicial to his own case. Cf. Commonwealth v. Leach, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 758, 768 (2009) (failure to object “is not only a sign that what was said sounded *22 less exciting at trial than appellate counsel now would have it seem, but it is also some indication that the tone [and] manner [of the comment] not unfairly prejudicial”). Finally, the judge told the jurors repeatedly they were the “sole judges of credibility of the [w]itnesses“ and “[o]nly you are going to. do this” (Tr. 11/245-246). These “instructions were clear, and we must presume the jury followed them.” Commonwealth v. Helfant, 398 Mass. 214, 228 (1982); Commonwealth v. Errington, 390 Mass. 875, 881 © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 14 (1984) (“We are unwilling to assume that the jury would not have heeded those instructions.”). III. The trial judge properly instructed that assault and battery may be committed by acts creating a “potential” rather than a “likelihood” of physical harm and, assuming an error, there was no risk of a miscarriage of justice where the evidence showed the defendant punched and broke the victim's nose and he claimed he acted in self-defense. The defendant claims for the first time that judge erred by instructing, on the third element of assault and battery, “that the touching either caused physical harm or had the potential to cause physical harm, or was an offensive touching done without her consent” (Tr. II/ 251, emphasis added; D.Br. 27-30. *23 He demonstrates no error, much less a risk of a miscarriage of justice. He cites to Commonwealth v. Dixon, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 653, 654 (1993) ( “assault and battery is the intentional, unprivileged, unjustified touching of another with such violence that bodily harm is likely to result”) and the Criminal Model Jury Instructions for Use in the District Court, Instruction 6.140 (MCLE 2009 ed.) (same). But both cite to Commonwealth v. Burke, 390 Mass. 480, 483-484 (1983), which holds, regarding the third element of assault and battery, that “the Commonwealth must prove one of the following: (1) that the touching was physically harmful; (2) that the touching was potentially physically harmful; or (3) that the touching was nonconsensual.” Thus, the judge's instruction correctly stated the law. Accord Commonwealth v. Winburn, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 1111 (2010) (Rule 1:28) (“To make out a case for criminal assault and battery, the Commonwealth must prove that the touchings at issue were (1) physically harmful, (2) potentially physically harmful, or (3) offensive and nonconsensual.”); Commonwealth v. Medina, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2011) (Rule 1:28) (“In a prosecution *24 for assault and battery, the Commonwealth must prove an intentional touching that was physically or potentially physically harmful, or nonconsensual.”). Even assuming an error, there was no risk of a miscarriage of justice. See Commonwealth v. Greco, 76 Mass. App. Ct. 296, 302 (2010). Repeated punches plainly carry a “likel[ihood]” of physical harm and there was overwhelming evidence that the punches were in fact harmful, as they fractured that victim's nose (Tr. 1/92-93, 130). Moreover, the defense theory was not that the punches had not occurred, or were not harmful, but that the defendant had acted in self-defense because he believed the victim was going to pull a knife on him (Tr. 11/225). In short, where neither the fact nor the harmfulness of the punch were “live issues” at trial, there was no such risk. Id. IV. The defendant has not met his burden to show an actual conflict of interest from the fact that his counsel, in his prior job as an assistant district attorney, prosecuted a defense witness, where the defendant offered only unsupported speculation that the witness “may well have harbored hostility toward” defense counsel. [FN16] FN16. Responding to defendant's argument V. Ellison, who testified for the defendant at the 58A hearing and at trial, had been prosecuted in 2008, *25 four years earlier, by the defense cousenl when he was an assistant district attorney in Essex County. The defendant contends that this created an “actual” conflict of interest requiring a more extended colloquy than was given, prior to judge's acceptance of the defendant's waiver. See Commonwealth v. Davis. 376 Mass. 777, 784-785 (1978). © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 15 Before the 58A hearing began, defense counsel reported the situation to the judge: I have spoken about this with [the defendant]. One of my witnesses, Tremayne Ellison, I prosecuted when I was in the DA's Office in Peabody in 2008 and Mr. Ellison remembers me. I don't feel personally that it's a conflict and I've discussed it with [the defendant]. He wants me to continue along with the representation (58A/3-4). The judge asked the defendant to indicate for the record “based on what your counsel has just informed the Court, that you don't have any problems and see no conflicts with counsel proceeding as your attorney, given what he's indicated to you.” Id. The defendant replied, “Yes, your Honor. I don't see no problem with it [sic]” Id. The defendant's entitlement to the colloquy depends on whether he has established an actual conflict of interest. *26Commonwealth v. Bonefont, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 54, 56 (1993), citing Commonwealth v. Walter, 396 Mass. 549, 559 (1986). “Our decisions distinguish between actual and potential conflicts of interest.” Commonwealth v. Croken, 432 Mass. 266, 272 (2000). “An ‘actual’ or ‘genuine’ conflict of interest arises where the ‘independent professional judgment’ of trial counsel is impaired, either by his own interests, or by the interests of another client.” Id, quoting Commonwealth v. Shraiar, 397 Mass. 16, 20 (1986). “It is ‘one in which prejudice is ‘inherent in the situation,’ such that no impartial observer could reasonably conclude that the attorney is able to serve the defendant with undivided loyalty.” Commonwealth v. Stote, 456 Mass. 213, 218-219 (2010), citations omitted. “An actual conflict requires reversal of a defendant's conviction under art. 12 of the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights without the necessity of showing that the conflict resulted in any prejudice.” Croken, 432 Mass. at 272. “It is the defendant's burden to prove an actual conflict of interest by presenting ‘demonstrative proof detailing both the existence and the precise character of this alleged conflict of interest’; we will not infer a conflict based on mere conjecture or speculation.” *27 Stote, 456 Mass. at 219, citations omitted. “[W]here a defendant can show nothing more than a potential conflict, the conviction will not be reversed except on a showing of actual prejudice.” Croken, 432 Mass. at 272, citation omitted. “Actual prejudice is measured against the standard in [Commonwealth v. Saferian, 366 Mass. 89, 96 (1974)], as in cases involving claims of ineffective assistance of counsel.” Id. See Commonwealth v. Miller, 435 Mass. 274, 282 (2001). Here, the defendant rests his claim of an actual conflict on the following thin reed: Ellison “may well have harbored hostility toward the attorney who prosecuted him in the recent past.” D.Br. at 38. This does not allege a conflict harbored by defense counsel at all, but rather a possibility that the defense witness's testimony “may” have been shaded by animosity toward his former prosecutor. The defendant cites to no case in which any similar situation has been held to show an actual conflict of interest on the part of defense counsel, and none exists. Cf. Commonwealth v. Lee, 394 Mass. 209, 218 (1985) (counsel's former employment as assistant district attorneys “does not establish, nor even permit the *28 inference, that counsel's loyalty to the defendants was impaired”). Contrast Commonwealth v. Connor, 381 Mass 500 (1980) (defense counsel previously represented Commonwealth's chief witness). Moreover, even assuming that the defendant has shown a potential conflict, he has shown no prejudice arising from it. He offers no support for the notion that Ellison felt animosity toward defense counsel based on the matter four years earlier, much less that this made a material difference in Ellison's testimony. Ellison testified favorably to the defendant. Cf. Commonwealth v. Filippidakis 29 Mass. App. Ct. 679, 682-684 (1991) (no prejudice shown from potential conflict arising from counsel's earlier representation of alternative suspect in the case; “there is nothing in the record to suggest that the attorney's performance here was adversely influenced by any residual allegiance to the” the suspect, who “took the stand and testified in the defendant's favor”); Commonwealth v. Bonefont, 35 Mass. App. Ct. © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 16 54, 56 (1993) (“The record contains no indication that the vigor of defense counsel's cross-examination of the victim was sapped because of his [representation of the victim's parents in an unrelated probate *29 matter]”). In short, “[c]onspicuously absent is a showing of something specific or concrete which resulted in ‘forfeiture of a substantial defense.”’ Bonefont, 35 Mass. App. Ct.at 56. In these circumstances, the 58A judge was well justified in accepting defense counsel's representations that he did not believe this presented a conflict and that he had discussed this with the defendant, who wished to continue the representation (58A/3-4). The judge confirmed this from the defendant himself, who saw “no problem” with it (Id.). The defendant's use of the double negative (“I don't see no problem with it”), did not, in context, render his statement unclear. Contrast D.Br. 39. Cf. Commonwealth v. Denham, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 724, 729 (1979) (the “fortuitous use of a double negative” in report did not “detract[ ]from an otherwise clear indication” that defendant was sexually dangerous). V. The defendant had no standing to assert any social worker/client privilege that a defense witness may have possessed where the witness himself did not assert the privilege.[FN17] FN17. Responding to defendant's argument VI. Before trial, the defendant moved in limine “that the Commonwealth may not question Donna Hiltz or *30 elicit any testimony that Ms. Hiltz was a client of the defendant, who was working as a community support worker. Such information is privileged and not relevant to any contested issue at trial” (R. 8). As noted, Hiltz did not testify. The motion made no mention of Ellison. At trial, Ellison testified on cross-examination as follows: [The prosecutor]: And the defendant was your case worker previously because you struggle with a substance abuse problem? [Defense counsel]: Objection. THE COURT: Overruled. You may answer. A. No. He was helping me issues mainly with (inaudible) I. was going through a Probate & Family Court matter which, I mean, I (inaudible) with my son. He was helping me with issues like that, you know. I mean, stuff like that. (Inaudible) therapy. I mean, my support system (Tr. 1/155). The defendant now contends this testimony constituted privileged social-worker client communications and its admission was “reversible error” D.Br. 41. This borders on the specious. Any privilege that existed was Ellison's to claim, not the defendant's. G.L. c. 112, § 135B (“[I]n any court proceeding ... a client shall have the privilege of refusing to *31 disclose and of preventing a witness from disclosing, any communication, wherever made, between said client and a social worker ... relative to the diagnosis or treatment of the client's mental or emotional condition”) (emphasis added). Under the statue, “[i]f a client is incompetent to exercise or waive such privilege, a guardian shall be appointed to act in the client's behalf.” Id. There is no indication that Ellison was incompetent. © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct.) Page 17 “Thus, as described in the statute[] creating th[is] privilege[], some action by the patient or client is necessary to ‘exercise’ the privilege therein created. The privilege is not self-executing.” Commonwealth v. Oliveira, 438 Mass. 325, 331-332 (2002). Commonwealth v. Pelosi, 441 Mass. 257, 261 (2004). Even assuming the defendant qualified as a social worker and could invoke the privilege on Ellison's behalf, and the question pertained to protected communications, “[w]here the statutory privilege in question leaves it to the patient to affirmatively assert the privilege, even a provider's assertion of that privilege may be treated as only a temporary precaution pending confirmation of the patient's own intentions.” Oliveira, 438 Mass. 332 & *32 n. 8. Ellison's failure to later invoke the privilege is dispositive. Finally, the defendant contends, in a single sentence and without further explanation, that Ellison's testimony set forth at p. 30 supra, prejudiced him because “the suggestion was that Frye was engaging in inappropriate behavior while in a position of trust and support” D.Br. 43. But nothing in the response did so. On this meager showing, the defendant's claim must be rejected. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, the Commonwealth requests that this Court to affirm the defendant's conviction. COMMONWEALTH, Appellee, v. Donald FRYE, Appellant. 2013 WL 4878568 (Mass.App.Ct. ) (Appellate Brief ) END OF DOCUMENT © 2013 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.