Major Depressive Disorder

advertisement

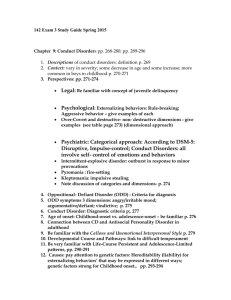

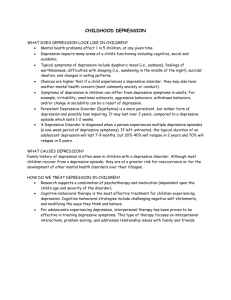

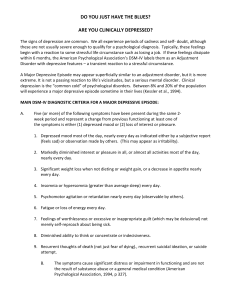

Major Depressive Disorder A Depressive Disorder Depressive Disorders • • • • • • • • Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder Major Depressive Disorder Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia) Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Substance/Medication Induced Depressive Disorder Depressive Disorder due to another medical condition Other specified Depressive Disorder Unspecified Depressive Disorder Depressive Disorders • Similarities • Differences History of Major Depressive Disorder in the DSM • Introduced DSM-III, 1980 • Additional Information in DSM-IV • DSM-5 changes in subtypes Major Depressive Disorder DSM-IV to DSM-5 • Not included in the DSM-5 are the following Diagnostic Criteria – B. The symptoms do not meet criteria for a Mixed Episode • Coexistence within a major depressive episode of at least 3 manic symptoms (not sufficient to meet for manic episode) is now a specifier – E. The symptoms are not better accounted for by Bereavement • Allow people to grieve without a label Quick Portrayal of Major Depressive Disorder • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twhvtzd6 gXA Symptoms of Depression Cognitive Physiological and Behavioral Emotional Poor concentration, indecisiveness, poor self-esteem, hopelessness, suicidal thoughts, delusions Sleep or appetite disturbances, psychomotor problems, catatonia, fatigue, loss of memory Sadness, depressed mood, anhedonia (loos of interest or pleasure in usual activities, irritability Major Depressive Disorder: DSM-5 A. 5 (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. Note: do not include symptoms that are clearly attributable to another medical condition (1) Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day (2) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (3) Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. (4) Insomnia or Hypersomnia nearly every day (5) Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (6) Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day (7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day (8) Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (9) Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition E. There has never been a manic episode or a hypomanic episode Note: This exclusion does not apply if all of the manic-like or hypomanic-like episodes are substance-induced or are attributable to the physiological effects of another medical condition. The symptoms are not better accounted for by Bereavement Criterion for Major Depressive Disorder A. 5 (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. Note: do not include symptoms that are clearly attributable to another medical condition (1) Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day (2) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (3) Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. (4) Insomnia or Hypersomnia nearly every day (5) Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (6) Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day (7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day (8) Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (9) Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide Criterion for Major Depressive Disorder B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition E. There has never been a manic episode or a hypomanic episode Note: This exclusion does not apply if all of the manic-like or hypomaniclike episodes are substance-induced or are attributable to the physiological effects of another medical condition. The symptoms are not better accounted for by Bereavement Need to Specify Severity and Course • • • • • • • • Mild Moderate Severe With psychotic features In partial remission In full remission Unspecified *Recurrent …as well as Specifiers without codes • • • • • • • • • With Anxious Distress With Mixed Features With Melancholic Features With Atypical Features With Mood-Congruent Psychotic Features With Mood-Incongruent Psychotic Features With Catatonia With Peripartum Onset With Seasonal Pattern Specific Notes about Children and Adolescents • Must also experience at least 4 additional symptoms drawn from a list that includes – Changes in appetite or weight, sleep, and psychomotor activity – Decreased energy – Feelings of worthlessness or guilt – Difficulty thinking, concentrating, or making decisions – Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation or suicide plans or attempts Specific Notes about Children and Adolescents • What does depression in children look like? – Mood • Irritable – This pattern needs to be differentiated from a pattern of irritability when frustrated • Cranky – At School – Physical problems Examples of Symptoms in Children and Adolescents • Social withdrawal or neglect of pleasurable activities • Appetite changes Onset, Course, Duration • Beginning in adolescence (12-16yo)(5-19yo) • Mean age at onset 30yo • Mean age start of treatment 33.5yo – Reflects amount of time depression often goes undiagnosed or untreated • Elderly onset – At risk for downward spiral • Course is Variable • Duration Remits or Variable – Lasts 6-13 months Course & Duration Specific to Youth • Course – Recurrence 1 to 2 years after remission = 20-60% – Recurrence 5 years after remission = 70% • Duration – Median Clinically referred sample = 8 months – Median Community referred sample 1-2 months Prevalence in Children and Adolescence • Lifetime Prevalence of 13 to 18 year olds • The difficulty with the numbers Prevalence in Children and Adolescence • Demographics (for lifetime prevalence) Sex and Age FIGURE 1 Cumulative lifetime prevalence of major classes of DSM-IV disorders among adolescents (N=10,123). Comorbidity and Differential Diagnosis • Highly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders – Anxiety – Dementia – Schizophrenia – Substance Abuse • Medical conditions – General – Neurological • Medications Accounting for Variance in Depression • Age and Genetics (phenotype expression) – The Sample MZM N = 106 DZM N = 100 MZF N = 106 DZF N = 100 DZOS N = 109 - Children 8-11 years, N = 252 - Adolescents 12-16 years, N = 244 Additive Genetic Shared Environment Non-shared Environment Accounting for Variance in Depression • Neurobiological: HPA axis Accounting for Variance in Depression • Environment – Early Life Stress – Lifetime traumas • • • • • Sexual abuse Physical assault Unexpected death Abortion Parental Loss – Sleep – Family • Parental bonding • Emotional tone of the home – Education – Substance “misuse” – Social Support Accounting for Variance in Depression • Personality – Neuroticism – Self-Esteem – Early-onset anxiety disorder – Conduct Disorder – Cognition A few models explaining Major Depressive Disorder • • • • • • • Biopsychosocial Model Interpersonal Theory Diathesis-Stress Model Cognitive Vulnerability-Stress Model Hopelessness Theory Beck’s Theory Maddie Marks’ Model Biopsychosocial Model Depression Interpersonal Theory Diathesis-Stress Model Depression Diathesis Stress Inherited predisposition Loss of loved one Cognitive Vulnerability-Stress Models of Depression • Hopelessness Theory • Beck’s Theory Hopelessness Theory Abramson et al., 1989 Negative Event Negative Cognitive Style Event-Specific Inferences 1. Stable-global causes 2. Negative consequences 3. Negative selfcharacteristics Hopelessness Symptoms of Hopelessness Depression Beck’s Theory (1967) Negative Event Negative Cognitive Style Cognitive Distortions Negative Cognitive Triad Negative Automatic Thoughts about Self, World, Future Symptoms of Depression Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder Suicide Completion Severity Suicidal Ideation Family history of suicidal behavior Internalizing Age Gender Adversity Childhood Social Support (low) SelfEsteem Neuroticism HPA-Axis Childhood Sexual Abuse Immune System Childhood Parental Loss Cognitive Substrates Early-onset anxiety disorder Structural Enlarged anterior Pituitary Adrenal Gland Genetic Risk Factors Externalizing Neurobiological Biology Conduct Disorder ADHD Early Adolescence Substance Misuse Late Adolescence Sleep Disturbed Family Environment Educational Attainment (low) Lifetime Traumas Adulthood The Last Year Past History of Major Depression Stressful Life Events independent of respondent’s own behavior History of Divorce Stressful Life Events dependent on respondent’s own behavior Difficulties Marital Problems References Arborelius, L., Owens, M. J., Plotsky, P. M., & Nemeroff, C. B. (1999). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. The Journal of endocrinology, 160(1), 1–12. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1600001 Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical psychology review, 26(1), 17–31. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003 Carlson, A., & Cantwell, P. (1980). Unmasking Masked Depression in Children and Adolescents. American Jourrnal of Psychiatry, 4(137), 445–449. Cole, D. A., Peeke, L. G., Martin, J. M., Truglio, R., & Seroczynski, A. D. (1998). A Longitudinal Look at the Relation Between Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents, 66(3). Dunlop, B. W., Kelley, M. E., Mletzko, T. C., Velasquez, C. M., Craighead, W. E., & Mayberg, H. S. (2012). Depression beliefs, treatment preference, and outcomes in a randomized trial for major depressive disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 46(3), 375–81. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.003 Eley, T., & Stevenson, J. (1999). Exploring the covariation between anxiety and depression symptoms: A genetic analysis of the effects of age and sex. Journal Of Child Psychology And Psychiatry, 40(8), 1273-1282. Grant, B. F. (1995). Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey of adults. Journal of substance abuse, 7(4), 481–97. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8838629 Gruenberg, A. M., Goldstein, R. D., & Pincus, H. A. (2005). Classification of depression: research and diagnostic criteria: DSM-IV and ICD-10. Biology of depression. From novel insights to therapeutic strategies. Hepgul, N., Cattaneo, A., Zunszain, P. a, & Pariante, C. M. (2013). Depression pathogenesis and treatment: what can we learn from blood mRNA expression? BMC medicine, 11(1), 28. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-28 March, J., Silva, S., Petrycki, S., Curry, J., Wells, K., Fairbank, J., … Severe, J. (2004). Fluoxetine, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, and Their Combination for Adolescents With Depression. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(7), 807–820. Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980-989. Mayo Clinic. (2012, February). Depression (major depression): Treatments and drugs. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/depression/DS00175/DSECTION=treatments-and-drugs National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Major Depressive Disorder Among Adults. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1mdd_adult.shtml National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Major Depressive Disorder in Children. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1mdd_child.shtml Pace, T. W. W., Mletzko, T. C., Alagbe, O., Musselman, D. L., Nemeroff, C. B., Miller, A. H., & Heim, C. M. (2006). Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. The American journal of psychiatry, 163(9), 1630–3. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1630 Peeters, F., Huibers, M., Roelofs, J., van Breukelen, G., Hollon, S. D., Markowitz, J. C., … Arntz, A. (2013). The clinical effectiveness of evidence-based interventions for depression: a pragmatic trial in routine practice. Journal of affective disorders, 145(3), 349–55. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.022 Schatzberg, A. F., & Nemeroff, C. B. (Eds.). (2009). The American psychiatric publishing textbook of psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. Vreeburg, S. A., Hoogendijk, W. J., Van Pelt, J., DeRijk, R. H., Verhagen, J., Van Dyck, R., … Zitman, F. G. (2013). Major Depressive Disorder and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Activity. Archives of general psychiatry, 66(6), 617–626. Walder, D. (2009). Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Death Studies, 33(3), 297-301. Watson, N. F. (2008). The Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of Neurology. Archives of Neurology, 65(2), 280. Zahra, S., Hossein, S., & Ali, K. V. (2012). Relationship between Opium Abuse and Severity of Depression in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes & metabolism journal, 36(2), 157–62. doi:10.4093/dmj.2012.36.2.157