Being Sociological

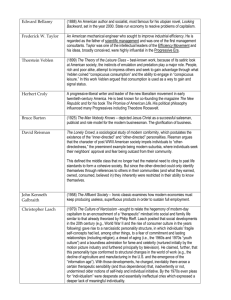

advertisement

Being Sociological Chapter 17 Consuming Sociology is the science that examines the relationship between production, exchange and consumption. Classical Sociology and Consumption • Sociology was born out of revolution and a strong theme in its development has been the production of social order in dialogue with principles of empowerment, distributive justice and social inclusion. • The issue of consumption touches all three of these principles at many points. Class Rule • Karl Marx maintains that social order is imposed by class rule. • For him the consumption of the working class is confined to productive consumption. • Marx appreciates that capitalism produces a cornucopia of plenty, in the form of luxury goods. • But he presumes that the consumption of these goods is deeply stratified and that ordinarily, the working class are allocated no more than is sufficient to reproduce their labour power. Broadly speaking, classical sociology produced four approaches to the question of consumption and social order: • Class rule; • Division of labour; • Power and rationalization; • Distinction and emulation. • Marx privileged relations of production over consumption in his study of capitalism. • As a result he fails to develop a satisfactory appreciation of capitalism’s capacity to generate limited economic redistribution and extended consumption as a front of social control. Two generations later, consumers are well aware that they are exploited. However, through marketing, design, branding, advertising and other public relations devices invented by capitalism, they are persuaded that there is no alternative to the system. The Division of Labour • Emile Durkheim’s approach to the problem of social order and, tacitly, to questions of consumption, focuses on the topic of social solidarity. • In his view, urban-industrial society produces a specific form of social solidarity that he refers to as ‘organic’. In his study Suicide (1897), Durkheim set out the perils of excess egoism. Where individuals experience weak connections with society, the result is friction and isolation. In terms of consumption, if too many people demonstrate excess in their propensity to consume the end is unrest, since the balance between the needs of society and the freedom of the individual is abated. • Conversely, where the relationship between individuals and society is too strong, individuals may feel crushed and suffocated. The result is that they decide that their personal interests are of no consequence. • Individuals cease to have the experience of freedom, or at least, conditioned freedom, which is necessary to their well being. • Hence, innovation, which is the spur of economic growth and social health, may be swamped by blind deference to the external order. • Durkheim’s approach points to the importance of consumption as a marker of association. What we consume expresses something about ourselves: that is, either the values, interests and aspirations that define us or that we would wish to have. • It suggests links between consumption and ritualized behaviour. It points to the importance of display and performance in reproducing solidarity. Power and Rationalisation • Max Weber is sociology’s greatest theorist of the struggle for power. • At the core of his theory is an interest in the relationship between structures of authority and forms of conduct. • He distinguishes three basic types of authority: charisma, traditional and legal-rational. Charismatic forms of leadership are based in people’s sincere belief that the leader possesses the gift of grace. It produces a condition in which followers cultivate close identification with the leader. With respect to consumption, followers will place everything that they have, including their own lives, at the disposal of their leader. Charisma is an ultimate form of authority in which no limits are recognized in regard to the cause in question. • Traditional authority means rule based upon precedent. Cases in point include obedience to the rule of hereditary monarchy, an elected religious leader, a caliph or a sultan. • Consumption patterns are governed by historical precedent. Innovation and deviation are given short shrift. • Instead, consumption and social behaviour in general are based on conformity. • Legal-rational authority means government on the basis of rational, bureaucratically administered directives. Authority derives from tabulated rules rather than the inspiration of a leader or the conventions of tradition. • Weber regarded this form of rule to be part of a wider process of rationalization. That is, the colonization of everyday life with systematized, impartially constructed, written rules of behaviour. • Legal-rational authority appears to grant maximum freedom to the individual and supremely secure social order, for rationalization is not the expression of individual or group interests, but the crystallization of the objective principles and protocols that are nominally in the best interest of all. • Basic to Weber’s discussion is the proposition that rational rule-bound existence encases individual freedoms in ‘an iron cage’. Where rules govern every scintilla of practice, individuals can never feel free. • With respect to consumption, this results in a regimented consumer who indulges in the act of consumption without passion or real fulfilment. • This view of consumption regards the consumer as keeping up with protocol rather than achieving genuine satisfaction. Weber points the way to understanding consumption as soulless, pedestrian and unfulfilling. Distinction and Emulation • The work of Thorstein Veblen (1899) opens up consumption as a means of exhibiting distinction. • It also sketches a model of how industrial consumption breeds conformity through emulation and stimulates the production of waste. • Veblen’s work treats consumption as the axis of society. • For Veblen, the enormous wealth created under capitalism produces a leisure class. While their riches insulate them from the need to engage in paid labour they do not exactly deliver freedom. • The leisure class demonstrates its liberty from the paid labour by cultivating characteristics of distinction that automatically signify their social separation and distance from the labouring class. The ‘Conspicuous Consumer’ Veblen (1899) introduced this term to refer to the spendthrift practices of the leisure class. Examples include expenditure on extravagant parties, building opulent mansions and gardens and the cultivating of expertise in activities that have no pecuniary value in industrial society, such as becoming adept in dead languages or acquiring the skills of the huntsman. • Veblen shows how wasteful consumption is a mark of status. • As wealth in society accumulates, conspicuous consumption will trickle down the social order. • As a result, the lower ranks emulate the spendthrift ways of the upper echelon. • Thus, waste is transformed into a characteristic of social distinction. Veblen’s approach demonstrates how waste is intimately related to advancing status. The Contemporary Sociology of Consumption • There is an enormous amount of work being done on patterns of consumption, inequality and distinction, over-consumption, risk, regulation and consumption and various subsidiary issues (Paterson 2006; Smart 2010). • All of this reflects the growing importance of the subject in everyday life, but there is no agreed thrust of direction. • Moreover, the ‘rediscovery’ of consumption privileges consumption over production and exchange. • An adequate sociological view of consumption must systematically link it to relations of production and exchange at all points. • In pursuit of this goal it is helpful to distinguish between two general approaches in the contemporary sociology of consumption: levelling perspectives and liquid perspectives. Levelling Perspectives • The characteristic propositions of this approach to the sociology of consumption are that consumer culture produces standardization, regimentation and pseudo-individualism. • Consumption is examined as a front of social control rather than an arena of choice. • This implies that capitalist consumer culture is self-correcting with powerful limits to resistance and opposition. • ‘Cool’ or ‘Smart’ capitalist corporations have cultivated informality between management and customers, developed ethical responsibility programmes which ‘invest in people’ both within and outside the corporation, and subscribe to anti-sexist, anti-racist and environmentally responsible business doctrines (Frank 1998; McGuigan 2009). • Questions of control ultimately lead to the issue of the production of ‘socially constructed’, ‘disciplined’ forms of subjectivity (Fiske 1989: 83). • This is the inverse of the neo-liberal view which is predicated in the notion of ‘the sovereign consumer’. • By highlighting the socially constructed, disciplined nature of consumer subjectivity, the concept of the sovereign consumer is exposed as a myth. • The levelling of consumer behaviour is necessary because the economic and social interests behind production, exchange and consumption demand that consumers have standardized responses to products. • Commodification is connected with dehumanization. Thus, Zygmunt Bauman (2007) completely rejects the proposition that consumption is about satisfying need. • As evidence he cites the ‘capricious’, ‘volatile’, ‘ephemeral’, ‘insatiable’ and ‘narcissistic’ character of modern consumer needs. What then is the purpose of consumption? For Bauman, it is nothing but an end in itself. • He argues that the interests behind production and exchange require life to be dominated by distraction and the absence of any sense of a realistic alternative, since this strengthens the security of the system by stifling movements of resistance and opposition. Branding • The concept of branding refers to the construction of a market culture that expresses standard responses to a brand. • The main instruments used to achieve this end are design, marketing and advertising (Ewen 1992, 1998). • Through these means consumers are continually persuaded to want new things. Pierre Bourdieu and cultural sociology • Bourdieu holds that taste is a marker of social distinction. What constitutes ‘good taste’ is partly related to the values of the dominant class. • There is a hierarchy in consumer culture in which the lower orders emulate the standards of the higher classes. • This is connected to class habitus. This refers to the system of classification, mental maps of the physical and social world and characteristics of belonging that are engrained in individuals and groups as a corollary of the socialization process. Distinction This refers to the conscious and unconscious ways in which individuals signify difference and particularity from other strata. Through fashion, political values, cultural concerns, psychological sensitivities, health awareness and other social markers, individuals position their identity in relation to others. Cultural Capital • This refers to the set of tastes, skills, knowledge and practices that relay social distinction. • Cultural capital is closely but not invariably related to economic capital. • Bourdieu is concerned to relate questions of taste and distinction in commodified culture more directly to social institutions. • Branding is a corporate means of objectifying distinction in a commodity. • Corporations quite deliberately seek to construct taste cultures around products. • In so doing they aim to inspire consumer desire and loyalty. George Ritzer’s theory of ‘McDonaldization’ (1993) Ritzer contends that modern society is beset by deep processes of regulation and compliance that limit human freedom and reproduce social control. In describing these processes as the ‘McDonaldization of society’, he identifies consumption as the fulcrum of control. • The McDonaldization thesis submits that the conditions of consumer management developed by the McDonald’s food chain both reflect and reinforce much wider conditions of regulation. • Four principles are highlighted: • Efficiency; • Predictability; • Calculability; • Control. • Individuals and groups are portrayed as powerless in the face of compelling social forces that engulf them and close down their capacities for response. • As is typical with the levelling perspective, the thesis presents societies converging towards higher levels of uniformity, regulation and compliance. • Levelling approaches are extremely compelling. • The flaw in these approaches is that questions of social control and discipline of subjectivity are overstated. Liquid Perspectives • These are approaches that place greater emphasis on the following: • The interpretive capacities of consumers; • The diversity of experience in consumer culture; • The superficiality of meaning; • The controls of built-in obsolescence and the effects of economic growth upon consumer identity. • This perspective views the fundamental problem in consumer culture to be one of surplus rather than scarcity (Bataille 1985; 1991; Baudrillard 1986, 1998). • Commodity culture is regarded as producing an over-abundance of meaning, although meaning is not necessarily very deep. Indeed, one of the central propositions of the Liquid approach is that modern consumers do not value durable meaning. • Rather, consumer culture has become an arena in which wants and longings are serial. ‘Solid’ and ‘Liquid’ Consumption • Solid consumption is ascendant in a context in which relations of production are dominant and work is the central life interest. • Producers exchange and consume products for the ‘comfort’, ‘esteem’ and long term use value such products deliver. • Product utility and durability are at the forefront of consumer choice. • Liquid consumption refers to a later (current) stage in consumer culture. • It flourishes in a context in which relations of production are dominant and non-work experience is valued as the central life interest. • In this phase in-built obsolescence is normalized. • Utility and durability are labelled as liabilities. Bauman’s ‘Modernity 1’ and ‘Modernity 2’ Modernity 1 refers to the tendency of modern social life to strive to establish territories, boundaries and clear rules of practice. The notion that work is compartmentalized from leisure and that each sphere has its own rules of conduct is an example. The central thrust of Modernity 1 is to establish unimpeachable, universal, rational criteria of action and judgement. Modernity 2 regards the development of modern life as inherently contradictory. Accordingly, territories, boundaries and rules are dismissed as a) arbitrary and b) subject to resistance and opposition that derive from ambiguities intrinsic to the idea of modern order. From this standpoint, in the long run, territories, boundaries and rules always precipitate reactions and counter-movements. Bauman’s discussion of solid and liquid consumption can be seen as too polarized. Solid and liquid forms co-exist. Boundaries, territories and rules in consumption are inherently contested and negotiated. That is, solid consumption always leads to liquid reactions and vice versa. • Liquidity also suggests impermanence, mobility and variety. Commodities and brands can be read in an infinite number of ways, creating the basis for consumer subcultures and individual reactions that perpetually out-run levelling and standardization. • Thus brand loyalty is commitment to a sign or system of signs. • Each branded commodity obeys the law of inbuilt obsolescence. Symbolic Commodity Capital • This derives from access to a desired commodity. Owning an Omega watch or a Rolls Royce provides access to the independent status attached to the commodity. • An Apple lets you download songs from iTunes and a Lamborghini gets you from A to B, but each is also a source of symbolic commodity capital, automatically linking the individual to a recognizable position in the social pecking order. Implications • If one holds fast to the Levelling perspective, positioning scarcity at the heart of the matter, one leads to questions of empowerment and distributive justice. • This kind of examination of consumer society is directed towards building a just, socially inclusive society, implying an alternative to the existing state of affairs. • The Liquid approach is cognizant of issues of waste, emulation and ecology. • However, coextensive with this is the recognition that consumption perpetually conceives new meanings and creates the basis for new types of association. • It is analysed as the basis for harnessing random imagination and unfocused energy that adds value to society. Jean Baudrillard (1986, 1998) • Baudrillard contends that the abundance of meaning produced in consumer culture compromises truth claims and programmes of reform and resistance. • He argues that it is no longer sufficient to try to understand commodities and brands as purely material objects. To truly grasp their significance in consumer culture we must see them primarily as signs. • The will to finally decode a sign is natural and compelling. According to Baudrillard, it is also futile, since all readings or decodings that purport to be ‘final’ simply reveal themselves to be signs themselves. • So consumer culture is caught in a fatal circle in which meaning abounds, but truth is perpetually absent. • The emphasis upon consumption as a process that fundamentally involves signs and representations connects with a specific view of consumer identity. • Modern conditions have generated a particular type of consumer, for whom participation in consumer culture rests on the power of the eye. Framing and coding consumption is examined through the metaphor of ‘the gaze’. • John Urry’s (1991) famous work on the tourist gaze is one of the most influential expressions of this approach. • Urry maintains that the anticipation that tourists have in visiting sites is framed by a network of power relations e.g. selective cultural traditions in literature, photography and music, tourist brochures, criminal bulletins, medical reports on the hazards of travel, and crime reports on ‘dangerous’ places. This network establishes a setting as ‘extraordinary’ and ‘exceptional’. • However, since media hubs establish the parameters of the tourist experience the authenticity of tourism is questioned. Conclusion • Consumption raises questions of power, inequality, identity and the ecological limits of exploitation. It is now central to sociological investigation and is likely to remain so. • The challenge is to consider it accurately in dialogue with relations of production and exchange. For there is no consumption without surplus, and no competition without scarcity. Discussion Point 1: Consuming Coffee • Do commodities like coffee and the pleasures they give us hide the ugly truth of capitalist society? • What elements of the Levelling and Liquid perspectives are found in the discussion of coffee? • If coffee disappeared tomorrow what would take its place? Discussion Point 2: Conspicuous Consumption and the Aspirational Ethos • What role does conspicuous consumption play in contemporary society? • Can conspicuous consumption and the aspirational ethos survive in times of austerity? • Can religion be a commodity?