Peregrine Fraud: A Case Study in Auditing and Cash Balance Manipulation

advertisement

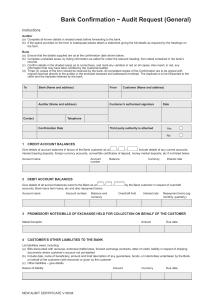

Peregrine – Twenty Years of Fraudulent Cash Balances INTRODUCTION “It’s crazy that he duped us with a P.O. box and Photoshop.” Commissioner Bart Chilton of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (Phillips et al. 2012). Nine days after his surprise Las Vegas wedding, Russell Wasendorf Sr., Chief Executive Officer of Peregrine Financial Group (PFG), was found unconscious in his car with a tube running from the exhaust pipe into the vehicle. Wasendorf was widely known in the futures industry as “Russ Senior,” since his son Russell Wasendorf Jr. served as the president of PFG. Three years earlier, Wasendorf had moved Peregrine from Chicago to the edge of the university town of Cedar Falls, Iowa. He quickly became an active and respected community leader, donating millions to the local university and several charities. Along with a suicide note, police found a statement in which the CEO admitted he had committed fraud for over 20 years. The note stated, “I have been able to embezzle millions of dollars from customer accounts at Peregrine Financial Group. Using a combination of Photoshop, Excel, scanners, and both laser and ink jet printers, I was able to make convincing forgeries of nearly every document that came from the bank” (Phillips et al. 2012). With this equipment, Wasendorf allegedly fooled regulators through an elaborate scheme that included forged bank statements, faked e-mails, and a bogus bank account at a post office box. The fraud was exposed when the National Futures Association (NFA) sent an audit team to review Peregrine’s books and pressure Peregrine into participating in a new electronic confirmation system for verifying accounts. Wasendorf fooled the NFA a year earlier after the regulator received an email from a bank employee on a Friday indicating that Peregrine’s account for customer balances had less than $8 million. The following Monday, the NFA received an email fax purportedly from the same bank employee with a hand-written note that the account balance was now $218.6 million (Phillips 2012). Apparently, the NFA auditors accepted this correction and did not follow up on how the bank could have made such a large error. A later investigation revealed that the fax was sent by Wasendorf (Huffstutter et al. 2012b). Included among the missing assets were 304 silver coins sporting the image of TV cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants. When the FBI searched the firm’s Cedar Falls headquarters, they seized SpongeBob coins worth about $375,000, based on the retail price per set of $259. The SpongeBob coins were the brainchild of a Peregrine unit called PFG Precious Metals Inc. and an Auckland, New Zealand-based minting firm, which began manufacturing the novelty items for the Peregrine unit in 2011 to sell to customers. PFG Precious Metals also sold gold and platinum coins (Saphir 2012a). WASENDORF’S BACKGROUND AND PEREGRINE FINANCIAL GROUP’S HISTORY Now known as the ‘Midwest Madoff’ (Epstein 2012), Wasendorf grew up in eastern Iowa. He was raised by a single mother following his father’s sudden death when Wasendorf was in kindergarten. He studied at the University of Northern Iowa, which he left to pursue a career as a documentary filmmaker. He was introduced to the futures industry in the 1970s through a trading program aimed at farmers. Wasendorf launched a financial advisory boutique in 1980 in the backroom of a barber shop (Huffstutter et al. 2012a). A correct bet ahead of the Black Monday market crash of 1987 provided the capital for the launch of Peregrine Financial Group three years later. Wasendorf said, “I named the company Peregrine because there is an expression in our business that you are ‘either predator or prey.’” The firm moved from Iowa to Chicago in 1994 just as the futures industry boomed with the advent of electronic trading. Peregrine moved back to Iowa in 2009, where Wasendorf was known for his restaurants and environmental and philanthropic work (Huffstutter et al. 2012a). The fraud shocked the small town of Cedar Falls where Peregrine was located, as well as the Chicago financial community. A closed sign now hangs on his high-end Italian restaurant my Verona. Wasendorf built a building in a wooded area outside of town designed specifically for the operations of the financial firm, with technology accessible throughout the building. A gym, day-care and cafeteria were available at no charge to all staff. The first person he hired for the project was a biologist to ensure that endangered species or woodlands would not be harmed. Now the building sits empty. “That property could be vacant for five years” says Jim Benda, a broker at a commercial realtor in Cedar Falls. “It’s going to be a difficult sale” (Louis 2012). ECHOES OF EARLIER SCANDALS Major frauds tend to imitate those of the past. First Securities Company of Chicago is one of the early significant auditor legal liability cases brought under the 1934 Securities Act. The perpetrator of the fraud, Leston Nay, received funds from friends to invest in an “escrow syndicate.” In fact, however, the syndicate did not exist and all of the funds were lost. To prevent detection, Nay instituted a “mail rule” and insisted that only he could open mail addressed to him. The fraud, which lasted about 30 years, ended in tragedy in 1968. Unable to make payments when a trustee of an estate attempted to redeem funds held by First Securities, Nay killed his wife and then himself. The Peregrine case is similar. To prevent other Peregrine employees from learning about the real bank balances, Wasendorf insisted that only he could open mail from the bank for 20 years. The largest of the financial frauds that were revealed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis involved Bernie Madoff. Like Wasendorf, Madoff apparently could not stop once he started the fraud. Madoff’s fraud began in the 1990s, though some believe that it started in the 1980s (Frank et al. 2009). Madoff was audited by a two-person CPA firm with only one practicing CPA. Similarly, Peregrine was audited by Veraja-Snellnig & Co., a one-person CPA firm. However, no one raised questions about why a financial services firm with hundreds of millions under management would employ such a small audit firm. CONFIRMATION OF CASH BALANCES Cash is perhaps the most basic audit area, and the audit work is typically performed by new staff auditors. One professor recalls hearing in new staff audit training – “cash is cash – you either have it or you don’t.” Faking cash balances does not seem plausible, and cash is rarely central to most major frauds. It is far easier to create fictitious inventory, receivables, or understate accounts payable. However, the fraud at Parmalat, which was revealed in 2003, highlighted the ability of companies to fraudulently overstate significant cash balances. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) auditing standards (AU-C 500) define an external confirmation as “audit evidence obtained as a direct written response to the auditor from a third party (the confirming party), either in paper form or by electronic or other medium (for example, through the auditor’s direct access to information held by a third party)” (AICPA 2009, 2011). Janvrin et al. (2010) identify several problems involving confirmation, including the need to evaluate the reliability of the response. Fictitious responses indicate a need to authenticate responses for balances involving significant risks, while responses involving collusion between the client and customer indicate a need for additional collaborative evidence in addition to confirmations. Confirmation of cash balances is a typical audit procedure performed by many auditors, and the AICPA provides a standard bank confirmation form (see Exhibit 1). The practice is so common that most auditors are surprised to learn that confirmation of cash is not currently required by auditing standards, although the PCAOB is considering requiring confirmation of cash balances (PCAOB 2009). Auditors typically confirm cash balances directly with the bank. In the Parmalat case, executives sent a forged confirmation to the auditors confirming 3.95 billion euros in a Cayman Island account. Potential fictitious bank balances and confirmations have recently arisen as a problem area in audits of Chinese companies (Rapaport 2011), but has not been a common problem in audits of U.S. companies. Wasendorf supplied the auditor with the address for a post office box that he controlled for the mailing of the confirmations. It was not just the external auditors that he fooled. Peregrine was audited by the National Futures Association (NFA) in February 2010 and May 2011. As noted in the opening quote, Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Commissioner Bart Chilton noted, “It’s crazy that he duped us with a P.O. box and Photoshop.” Further, NFA President Daniel Roth stated on July 25, 2012 that, "The sheer volume of forged documents that were produced as part of this scheme is staggering, and had to occur on a daily basis." However, the use of Photoshop to create forged documents may not be so crazy, as suggested by Caster and Verardo (2007), who found that some forms of technology, such as scanners and printers, may weaken traditional audit procedures and actually serve as an enabler to a fraudster. ELECTRONIC CONFIRMATIONS The process of confirming written bank balance confirmations had largely been unchanged for decades until the Parmalat fraud. The forged confirmation in the Parmalat fraud involved an alleged account at Bank of America. Following the fraud, Bank of America announced that it would only process confirmations sent electronically through a third-party intermediary, Capital Confirmation. Capital Confirmation, similar to other electronic confirmation providers, uses a secure web-based approach (e.g., Confirmation.com) to assist auditors with electronic confirmation. Electronic confirmations provide verification through authentication of all parties involved in the confirmation process (audit firm, client, and financial institution), improving audit efficiency and effectiveness (Aldhizer and Cashell 2006). The NFA began using Confirmation.com in the wake of the October 2011 collapse of MF Global Holdings, a company led by former New Jersey governor Jon Corzine. The NFA began to demand that futures brokerages submit to its e-confirmation services in summer 2012. After significant pressure, Wasendorf agreed to authorize the NFA to electronically confirm Peregrine’s cash balances the day before he attempted to kill himself. EPILOGUE Wasendorf recently entered into a plea agreement regarding this case (Harris and Witosky 2012). Details of the plea agreement remain secret. However, news reports of the missing assets recovery investigation provide little hope that investors will receive a significant portion of the $220 million in missing funds stolen over the past 20 years. Thus far, investigators have learned that most of Wasendorf’s assets, including his luxury Iowa home, downtown Chicago apartment, and private plane, were highly mortgaged. Further, officials are investigating a $50,000 deposit made by Wasendorf to his new wife’s daughter the morning of his suicide attempt, missing gold valued at $60,000, and 304 missing silver SpongeBob SquarePants coins valued at $20,000 (Saphir 2012a). Peregrine filed for bankruptcy within a week of Wasendorf’s suicide attempt and over 300 employees are now laid off and 17,000 futures customers and 7,000 trading clients were forced to find alternative trading services (Saphir 2012b). CASE REQUIREMENTS 1. What are the requirements for confirmation of cash balances under U.S. auditing standards? Do you believe confirmations of cash balances should be required by U.S. auditing standards? Why or why not? 2. Another account many auditors confirm is accounts receivable. U.S. auditing standards currently require confirmation of accounts receivable in most situations. However, international auditing standards do not require confirmation of accounts receivable, citing cultural differences between countries as one reason why requiring receivable confirmation would not be appropriate. For example, in some countries, a request to confirm an account balance would be viewed as insulting. Do you believe confirmations of cash and accounts receivable balances should be required by international auditing standards? Why or why not? 3. Peregrine was audited by a one-person CPA firm? Do you believe this played a role in the failure to detect the fraud? 4. The fraud was revealed when regulators moved to electronic confirmation of bank balances. What are the advantages of electronic confirmations? 5. What are the risks associated with electronic confirmations? How can an auditor gain confidence in the reliability of responses received electronically? 6. Should electronic confirmation of cash balances be required? Could standard written bank confirmations have been effective in detecting the fraud at Peregrine? 7. Given the relatively small number of electronic confirmation providers, what happens if: a. an electronic confirmation provider’s server goes down for an extended time or if the server is compromised by hackers? b. an electronic confirmation provider experiences financial problems or goes out of business?