Dante-85

advertisement

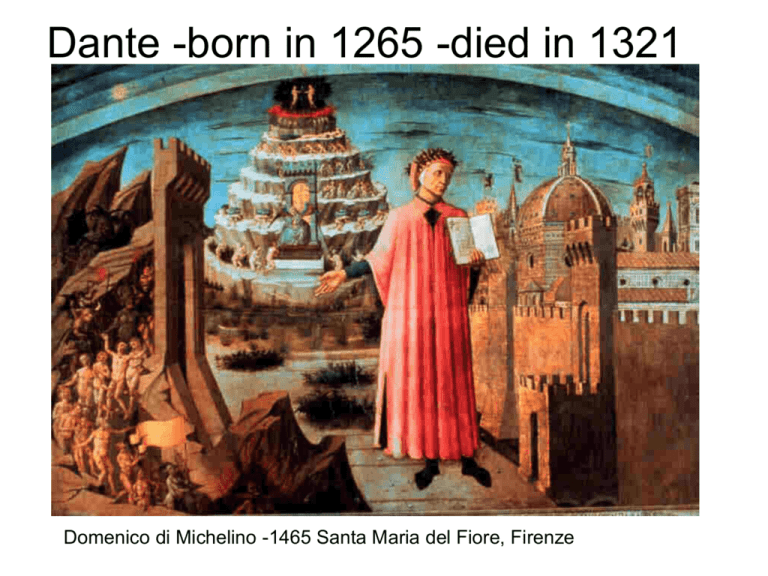

Dante -born in 1265 -died in 1321 Domenico di Michelino -1465 Santa Maria del Fiore, Firenze Florence ITALY AND TUSCANY Dante’s house in Florence The Baptistery in Florence where Dante was baptized was the cathedral at that time. The dome of the Baptistery is covered with mosaics, which depict devils, angels, and after death punishments. • Santa Maria del Fiore • built between 1296 and 1436 Santa Maria del Fiore, cupola (1420-1434) • Dante was born in 1265 in Florence. • As a young man in 1289, he fought in the battle of Campaldino which marked the victory of Dante’s Guelph party. • In 1295 he began his political career. • He was exiled from Florence (Firenze) in 1302. • He started writing the Divine Comedy in 1306 when he was in exile. • He died in 1321 in Ravenna. Dante’s Statue in Florence Santa Croce, S. Croce, Firenze, Italy; 1294-1442; by Arnolfo di Cambio Firenze - Ponte Vecchio What Florence and New Orleans have in common: giglio – symbol of Florence The year 1300 • Pope Boniface VIII proclaims the Jubilee Year. • Dante is 35 years old. • June 15-August 14: Dante is named a Prior, one of the six highest magistrates in Florence. • Easter time: Fictional date of the journey of the Divine Comedy • Beginning of the factional struggles between the Cerchi and the Donati (Bianchi and Neri) Tuscany The Guelphs supported the Roman Catholic Church. Pope Boniface VIII sent Charles of Valois to Florence in 1300 to end the feud between the Black and White Guelphs. In 1302 Dante was exiled. The statue of Boniface VIII is at The Museum of the Opera del Duomo in Florence. The Ghibellines supported the Holy Roman Empire. The castle of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II is located in Prato, just north of Florence. It was built between 1237 and 1248. Political Division in Tuscany •In Florence the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, which represented rival families, fought from 1215 to 1278 when Florence became the head of the Guelph league in Tuscany. •Siena was Ghibelline, because it sought the support of the emperor against the Florentines and against the rebellious nobles of its own territory. •Lucca was Guelph because it needed the protection of Florence. •Prato was Guelph •Pisa was Ghibelline •Arezzo was Ghibelline The political parties in Florence and Tuscany • • • • The Ghibellines supported the Holy Roman Empire. The Guelphs supported the papal party. The two parties fought between 1215 and 1278. The Guelph party took over. – Dante was a Guelph (Guelfo). • Around 1300 the Guelphs split into Blacks (Neri) and Whites (Bianchi). • The Whites opposed the tyrannical power of the Pope and started siding with the Ghibellines. • Dante was a White. • The Whites ruled until 1302. • While Dante was sent as an ambassador to the Pope, the Blacks took control of the city. • He could not return to Florence. SIENA was ghibelline, therefore enemy of Florence The Cathedral of Siena Arezzo was Ghibelline. In Canto XXIX Dante meets Griffolino of Arezzo, who was punished for alchemy. Prato, located close to Florence, was and still is an important industrial town for the manufacturing of textiles. The Cathedral of Prato • Pisa, a stronghold of the Ghibellines, was a powerful maritime republic at war with the Guelph league and with Genoa. Lucca • Etruscan origin • Wealthy on silk and banking • Mantained its independence Pistoia, a ghibelline town, was overtaken by Florence’s Guelph party in 1254. In cantos XXIV, 97 and XXV, 1 Dante mentions Vanni Fucci, a black Guelph who stole holy objects from the Cathedral in Pistoia. May 7 1300: Dante is sent as ambassador to San Gimignano to persuade its citizens to join the Guelph party. San Gimignano San Gimignano PIENZA Tuscan countryside Inferno XIII –” the wilds between Cecina and Corneto “ Once an undeveloped marshy area along the southern part of Tuscany, after a project of land reclamation, it is today one of the most beautiful unspoiled areas in Italy. Tuscan coast in Maremma PRATO Dante’s Tomb in Ravenna CANTO 1 Lost in a wood, Dante meets a leopard, a lion, and a wolf who block his path. The leopard is the symbol of lust or excessive passion, the lion of pride and violence, and the she-wolf of fraud and betrayal. The First Circle or Limbo • Here the innocents will remain forever with no hope of ever seeing God. • Dante and Virgil join in conversation the great poets of the classical times: Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan. • It is a rather pleasant landscape with light and green meadows, like the Elysian Fields described by Virgil in the Aeneid. Charon ferrying the souls across the Acheron to the first circle Michelangelo Charon (detail from the Last Judgement, Sistine Chapel), 1536-41 Upper Hell and the Sins of Incontinence • Second Circle – Lust: Paolo and Francesca • Third Circle – Gluttony: Ciacco • Fourth Circle – Avarice and prodigality: Popes and cardinals • Fifth Circle – Wrath: Filippo Argenti The Styx and Phlegyas Sixth Circle: the Heretics • This is the first circle inside the City of Dis. • Farinata and Cavalcante are punished here by burning forever in open coffins. Illustration by William Blake The river of boiling blood: the Phlegethon (Salvador Dali’) The Seventh Circle • Here the violent are punished in three rings. • 1) Violent Against their Neighbors (tyrants and murderers). These souls are plunged into a river of boiling blood: the river Phlegethon. They are watched over by the Centaurs. • 2) Violent against Themselves (suicides). It is an unnatural forest with leafless trees. These trees are the souls of the suicides. Dante talks to Pier delle Vigne, personal secretary of Frederick II. The trees have no leaves because the Harpies keep plucking them as they sprout. Among the trees Dante sees the souls of the squanderers, chased by bitches. • 3) Violent against God and Nature. These ring is divided into three zones: blasphemers, sodomites, and usurers. Virgil talks to Capaneus stricken by Zeus's bolt for his rebellion. Then Dante talks to his teacher Brunetto Latini, and later he sees three Florentines, at the edge of the circle. The usurers who have sinned against God’s laws of nature are also punished here. Canto XIV, 79-80 From the Phlegethon, small streams pour out, like the sulphurous waters of the Bulicame near Viterbo, north of Rome… Inferno (xviii, 29) - Dante compares the sinners passing along one of the bridges of the Malebolge in opposite directions, to the crowds crossing the bridge of the Castel Sant' Angelo on their way to and from St. Peter's in Rome during the Holy year of Jubilee in 1300 Castel Sant’ Angelo Le Malebolge The eight circle of hell is divided into ten sections. Each “bolgia” is a depression in the ground similar to a ditch. The “bolge” are connected by bridges that span over the ditch and lower to the next level. Canto 18 - Le malebolge There is a place in hell, called Malebolge, All of stone and iron of color, Like the circle that all around surrounds it. In the very middle of the evil field Appears a well, rather large and deep. Of whose location I will explain. That circle which remains, then, is round Between the well and the foot of the tall hard wall And the bottom is divided into ten valleys. Just as, where to protect the walls Many and more ditches surround castles, The part where they are, makes a figure, Same image here those were forming: And like in these forts from their ramparts Small bridges go to the outside shore, So from the rock juts are projected to connect the levees and the ditches, Until the well which cuts and connects them. • • • • • • • • • • First bolgia – The Panderers and Seducers Second bolgia – The Flatterers Third bolgia – the Simoniacs The Fourth bolgia – the Fortunetellers Fifth bolgia –The Barrators or grafters Sixth bolgia – the Hypocrites Seventh bolgia – the Thieves Eighth bolgia – The Evil counselors Ninth bolgia – The Spreader of discord Tenth bolgia – the Falsifiers » » » » Of metals Of persons Of coins Of words • Bertrand de Born exemplifies the law of contrapasso in canto 28. The contrapasso • The punishment fits the crime. The souls are condemned to endure the perpetuation of their behavior or its opposite. • For example, the Fortunetellers have their heads on backwards and must walk "backwards" for all time. In life, they attempted to "see" the future, now in death they must see the past. Dante compares the giants who guard the ninth circle to the castle of Monteriggioni outside Siena (Inferno canto XXXI, vv. 40-45 ) Canto 31 – The Giants Bologna’s Towers “della Garisenda and Degli Asinelli” Dante compared Anteus to the Garisenda The ninth circle is divided into four sections. •Round 1: Caina (those who betrayed their relatives) •Round 2: Antenora (those who betrayed their country) •Round 3: Ptolomea (those who betrayed their guests) •Round 4: Judecca (those who betrayed their benefactors) Pisa and Count Ugolino • Pisa was a town divided between power of the church and state. • To obtain power Count Ugolino, a Ghibellin, betrayed his party. • By siding with the Guelphs, he gained control of the city. • Ruggieri was an archbishop who at first supported count Ugolino, but then betrayed him. • Count Ugolino was imprisoned with his children and let die of starvation. PISA LUNGARNO TORRE DELL’ OROLOGIO IN PISA Canto 30 CONTE UGOLINO was imprisoned here and let die of starvation PISA William Blake Inferno's characters from history and arts, from mythology, from Dante's real life • The guardians of Hell • Dante’s contemporaries • Historical figures and literary characters Dante’s contemporaries • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Beatrice – personifies “pure and absolute love” Ciacco – the glutton who must have known Dante Paolo and Francesca - two lovers who were killed by the Francesca’s husband Filippo Argenti – a Black Guelph, Dante’s enemy, found among the Wrathful in the river Styx. Farinata - A prominent leader of the Ghibelline party who saved Florence from destruction when the Ghibellines won in 1260. He is punished among the heretics. Cavalcante de’Cavalcanti - father of Dante’s friend, Guido de Cavalcanti Pier della Vigna - Former advisor to Emperor Frederick II who committed suicide when he fell into disfavor at the court. Brunetto Latini – a poet and political leader whose ideas influenced Dante Pope Boniface VIII - Dante’s enemy accused of simonism The Navarrese barrator - who tricks the devils causing them to fall in the sticky tar Vanni Fucci - of the Black party, a thief punished in the Seventh Pouch of the Eighth Circle of Hell who prophesies the defeat of the White Guelphs. Guido da Montefeltro - A Ghibellin advisor to Pope Boniface VIII Bertran de Born (1140-1215): was a troubadour poet who carries his decapitated head by the hair Geri del Bello - Dante's cousin, a troublemaker who caused the feud with the Sacchetti family Gianni Schicchi – impersonated Buoso Donati, who had just died, and dictated a new will in favor of Buoso’s nephew Simone. Count Ugolino - betrayed Pisa and was betrayed by the Archbishop Ruggeri who shares his punishment in the lowest circle of hell Characters from history or literary works • Pope Celestine V: Became Pope in 1294. Withdrew from the world and renounced the papacy, allowing Boniface to become pope. He is with the “uncommitted.” • The poets Homer, Horace, Ovid, Lucan in Limbo • The philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle in Limbo • Dido, Achilles, Helen, Paris among the lustful • Attila and Alexander among the tyrants • Tiresias and Chalcas among the soothsayers • Ulysses and Diomedes among the False Counselors • Mohammed who caused the division between Christianity and Islam • Caiaphas: Jewish high priest; head of council which condemned Jesus. • Sinon the Greek who lied to persuade the Trojans to bring the wooden horse inside the town • Judas who betrayed Jesus • Brutus and Cassius who betrayed Cesar The Guardians of Hell • • • • • • • • • • Charon (circle 1) Minos (circle 2) Cerberus (circle 3) Plutus (circle 4) Phlegyas (circle 5) The Furies (circle 6) The Centaurs and the Minotaur (circle 7) The Harpies (circle 7, ring 2) Geryon (circle 8) The Giants (circle 9) At the beginning of second circle Minos judges the souls and assigns them to their place. Cerberus, the three-headed dog guards the gluttons punished in the third circle. Plutus, Roman god of wealth William Blake 1757-1827 Phlegyas is the ferry man who transports Dante across the river Styx in the fifth ring of hell. The Furies • They guard the gates of the city of Dis at the sixth circle. • They have serpents in their hair. The Centaurs, guardians of the 7th circle where the violent are punished Floor Mosaic in Ostia Antica The Minotaur also in the seventh circle 7 A bull-headed man who lived in Crete He was imprisoned in the Labyrinth and killed by Theseus The Harpies (7th circle) • Half women- half birds Geryon A monster who helps Dante and Virgil to reach the eight circle by carrying them on his back Canto 31- The Giants Botticelli His face appeared to me as long and large As is at Rome the pinecone of Saint Peter's… (Inferno, Canto XXXI) The bronze pinecone is located in one of the Vatican’s courtyards. Map of he Purgatorio Map of Paradiso Dante and the Italian Language The poetry The Divina Commedia is composed in terza rima, a three-line stanza called terzina,which uses chain rhyme in the pattern a-b-a, b-c-b, c-d-c, d-e-d. Each line contains eleven syllables. Therefore each terzina contains 33 syllables. Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita mi ritrovai per una selva oscura ché la diritta via era smarrita. Ahi quanto a dir qual era è cosa dura esta selva selvaggia e aspra e forte che nel pensier rinova la paura! Tant'è amara che poco è più morte; ma per trattar del ben ch'i' vi trovai, dirò de l'altre cose ch'i' v'ho scorte. Terzina Nel /mez/zo /del /cam/min /di /no/stra/ vi/ta mi /ri/ tro/vai/ per/ una/ sel/va/ o/scu/ra Ché/ la/ di/rit/ta/ vi/a/ era/ smar/ri/ta. The language of the Divine Comedy Dante’s use of his native Tuscan dialect in The Comedy helped to unify the Italian language, which is rooted in Tuscan more than in any other Italian dialect. Before Dante, major literary works were almost always written in Latin, the language of the Roman Empire and the Catholic Church; no one had considered the vernacular capable of poetic expression of the caliber of Virgil’s Aeneid, for example. In defense of this language Dante wrote De Vulgari Eloquentia. Dante himself felt compelled to defend the legitimacy of literature written in the mother tongue in his treatise De Vulgari Eloquentia ("Of Literature in the Vernacular," 1304-1306). Paradoxically, Dante wrote this treatise defending the literary legitimacy of the vernacular in Latin, not Italian, because he wanted it to be taken seriously!