Into the Inferno

advertisement

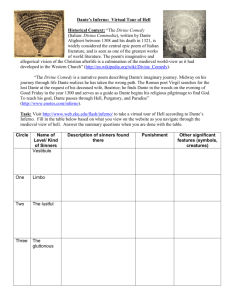

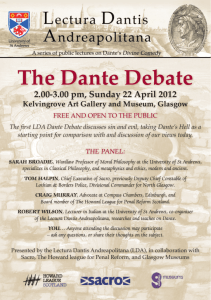

The Inferno: Into the Inferno Feraco Myth to Science Fiction 27 October 2014 Dante was born in late May or early June of 1265, under the constellation Gemini. His mother would pass away five years later, with his father following roughly a decade later, leaving Dante parentless before he reached what we consider the age of adulthood. When one reads The Inferno, Dante clearly wants the reader to avoid the misery of isolation. He believed very strongly in the idea of belonging to something larger (i.e., society), and drew comfort from that; one wonders whether his particular familial history contributes to his ideas. Fortunately, his father remarried before he died, providing Dante with both additional company and educational opportunities. Dante’s literary studies as a youth brought him into close contact with many significant writers, although scholars differ vociferously as to who actually influenced Dante. For example, Brunetto Latini (who we find in the third round of the seventh circle) taught Dante “how man becomes eternal” – i.e. how man can live on forever through his impact on the world, such as through writing. Dante also met Guido Cavalcanti, another poet of renown, at this time; Cavalcanti would play a pivotal role in the future. But most importantly, Dante also encountered a girl named Beatrice Portinari. He first met her at the age of nine, and instantly fell in love; he did not see her again until she was 18. Beatrice married – and died – young, passing away at 25. She appears in Dante’s works alternately as the object of his love and as the inspiration for his art. Dante entered a world – medieval Florence, Italy – that was coming apart at the seams. We see Florentine society divide along factional fault lines time and again during the 13th and 14th centuries, like a cell that continues dividing without properly replacing the substance it’s lost. The first divides appeared – as they always seem to – between those who craved change and those who wished to preserve the status quo. Prior to Dante’s birth, Florence operated as a largely feudal – and stratified – society. But as Florence’s trade market boomed, the feudal underclass grew wealthier, and the city’s cultural makeup began shifting as they integrated themselves into the Florentine economy. There were forces that wished to see society fall under even more direct church control (the Guelphs) and landed aristocrats who swore to uphold the principles of feudalism and service to an emperor (the Ghibellines). The Ghibellines supported the old order, while the Guelphs supported the new. As these things often go, new supplanted old, old tried to re-supplant new and failed, and new proceeded to try establishing a death grip on the power it just obtained. The Guelphs eventually drove the Ghibellines from power, and successfully repelled counterattacks over the next few years – including a particularly effective one a year after Dante entered the world, led by Farinata degli Uberti (whom Dante will see in Hell). And as the years passed, Florence became an almost-uniformly Guelph city. Dante’s family, while nominally composed of Guelphs, wasn’t very politically active. Dante, however, was: We see him enroll in the Guild of Physicians and Apothecaries – one had to be a Guild member in order to serve in government – and quickly ascend the political ladder. He even marries Gemma Donati and begins fathering children. (He confesses in later works that he felt unfaithful to Beatrice’s memory as a result.) In the meantime, the dominant Guelphs, having grown complacent after thirty years of unchallenged power, began to split into factions. By the time Dante had moved from an ambassadorial position to a spot as a supreme magistrate (a.k.a.“prior”) in 1300, Guelph unity had given way to the Neri (“Blacks”) and Bianchi (“Whites”) factions. Corso Donati – Gemma’s brother – led the Blacks, while Guido Cavalcanti led the Whites. Dante only needed to serve as a prior for two months; the role, although extremely elite (only six men served as priors at any given moment), was a short-lived one if one proved ineffective. He was a moderate White, a member of the dominant faction. And when the priors moved to dispel some of the tensions by banishing Corso Donati and Guido Cavalcanti… …Dante went along with them. I find this particularly interesting, considering that betrayal serves as the sin Dante punishes most viciously in The Inferno. Meanwhile, having lost a great deal of influence during this particular period, the Blacks decided to make a power play. They were more loyal to Pope Boniface VIII – a man who would become Dante’s arch-nemesis – and begged him for intervention. Boniface, as well as the larger church, craved more control over Florence and its politics. To achieve this end, Boniface sent a “peacemaker”, Charles of Valois, who assumed direct control in the Pope’s name. Charles’s ostensible “peacemaking” didn’t last long. He allowed the Blacks to take power once he situated himself in Florence (over the Whites’ vociferous objections), and the Neri faction immediately began murdering and pillaging its old rivals. This power shift quickly gave way to a series of trials meant to purge remaining White elements from the system. When the trials began, Dante had already traveled outside of Florence as part of a group intending – ironically – to “appeal for a change in papal policy towards the city and to protest the machinations of the Neri.” He was convicted of crimes in absentia – graft (essentially skimming money he was supposed to allot for other purposes) and corruption (fraudulent activity in office) – that pop up again in The Inferno’s Malebolge. At first, Dante stayed away voluntarily, apparently hoping that things would blow over (an unrealistic hope, considering that the Pope silently backed Charles’s moves). When he was sentenced to immolation in 1302, however, his exile became mandatory. “To [Dante], a penniless exile convicted of a felony, separated under pain of death from home, family, and friends, his life seemed to have been cut off in the middle.” Between the time of his exile and his death in 1321, Dante traveled all over Italy, staying with patrons, studying philosophy, and writing while perpetually eying Florence’s stillturbulent politics. Other exiles pinned their hopes on the various fights that still broke out between the Ghibellines (remember them? Still going at it) and the dominant Blacks. True, if the Ghibellines returned to power, it would probably be the end of the Florence they’d built…but at least they’d get to go home. Dante, however, refused to turn on his city, choosing instead to reject all party designations and become “a party by himself.” His intentions were undercut in 1315, when the Ghibellines had gathered enough strength to attack the Guelphs once more. This led to Dante’s being branded as a Ghibelline and a rebel (this was also true of many other “enemies”), crimes punishable by decapitation. For those keeping score, this meant Dante had moved from being burned to being beheaded. And while one may see this as a distinction without a difference – both being ways to kill a man they weren’t going out of their way to catch – Dante’s sentence in 1315 carried a different wrinkle: While his sons with Gemma had previously been spared punishment, they were also included in the sentence – even though they’d never seen Dante after 1302. Yet one year later – 1316 – Dante was offered a chance to return to Florence. All he had to do was meet certain conditions, conditions which happened to be designed to humiliate him (the public payment of a heavy fine, the public performance of penance, etc.). Dante refused. Is this, then, the glorious recall of Dante Alighieri to his native city, after the miseries of nearly fifteen years of exile?...No! This is not the way for me to return to my country. If another can be found that does not derogate from the fame and honor of Dante, that will I take with no lagging steps. But if by no such way Florence may be entered, then will I enter Florence never. What! Can I not everywhere behold the sun and stars? Can I not under any sky meditate on the most precious truths, without first rendering myself inglorious, nay ignominious, in the eyes of the people and city of Florence? Dante’s time with his patrons (most notably Cangrande della Scala, a man Dante greatly admired and hoped would lead Florence out of its darkness) came to an end when he grew sick and died at the age of 56 of malaria. He didn’t quite make it through his “alloted” 70 years (although, in all fairness, he couldn’t have foreseen such a thing while writing The Inferno). Even so, Dante embodies Latini’s lesson; our fascination with him is greater than with any other figure from his era. He left a philosophical, linguistic, and literary legacy that would be the envy of any man – a legacy we’ll study in greater detail as we continue examining his most enduring work. ----- As for his famous creation, Dante doesn’t invent Hell so much as remix it. He takes the general idea of an afterlife reserved for those who deserved punishment and fused it with both old ideas and his own concepts regarding justice and morality. Aristotle, for example, inspired Dante’s hierarchy of incontinence, viciousness (“brutishness”), and malice; we have the SheWolf, the Lion, and the Leopard. (In some translations, the Leopard represents incontinence, and the she-wolf represents fraud. This may explain the apparent inconsistency between how greatly Dante fears the she-wolf and how “mildly” his Hell treats sins of incontinence; another explanation could simply be that Dante tends to ease up on the sins he feels more personally tied to…) Sins of incontinence or desire are punished in circles two through five, those whose sins involved violence occupy circle seven, and perpetrators of fraud are consigned to circles eight and nine. Having established fairly Aristotlean foundations for his Hell, Dante turns to medieval Christian doctrine in order to identify both which sins should be cataloged and where each belongs. This is why we see most of the Seven Deadly Sins, and why even the Virtuous Pagans – those who were good people, but lacked faith – end up in Limbo, the first circle. With that said, Dante does add his own touches to Hell. Limbo, for example, had been pre-established within doctrine – but it was meant for the souls of, say, unbaptized children. Dante’s placement of the great artists who’d lived and died before Christ’s birth in the same circle represents some fairly significant editorializing on his part. Another one of Dante’s touches is more chilling; he argues that those who betray their guests have their souls ripped from their bodies at the moment of betrayal, and that demons inhabit their empty shells from then on. Finally, Dante’s “vestibule” – the place just outside of Hell reserved for cowards, as well as the angels who did not side with God – is his own invention. Given the events of Dante’s life, it’s not surprising that he’s disgusted with those whose morals are defined by their opportunism, and who refuse to choose between good and evil. Dante now has a conceptual framework of Hell, rationale for its organization, and an idea of where he’ll go over the course of his journey. But what goes in Hell? Even though it’s an allegory, we can only buy into it if we believe in the physical experiences Dante presents. The Inferno documents a spiritual journey exclusively in physical metaphor, so Hell can’t just be a conceptual place – it needs to be populated. We have to sense things – see great beasts, confront monsters, witness torments – and shudder at the horrors we experience; then, and only then, can we begin unpacking what each thing “really means.”This was a book born of anguish, after all – an attempt by a single man to resolve the questions that harried him. Unless we engage with The Inferno at an emotional (as well as intellectual) level, we can never connect with Dante at his. In order to fill his empty Hell, Dante reaches back into mythology, religious texts, and epics. Virgil’s Aeneid, which features a protagonist’s visit to the Land of the Dead, provides both a point of comparison and contrast. While Virgil’s underworld was much less physically realistic than Dante’s, the various creatures, rivers, and geographical features the former employed serve much the same purpose in The Inferno. Raffa notes that Dante and Virgil both use Charon, Minos, Cerberus, Plutus, Phlegyas, the Furies, the Minotaur, the Centaurs, the Harpies, Geryon, and the Giants: Each serves both as allusion and as metaphor within Dante’s allegory. Clearly, Dante’s choice of Virgil as his guide through Hell isn’t arbitrary; who better to know how to deal with the monsters we find than the man who documented them over a millennium earlier? In conclusion, Dante’s Hell is both his own and not his own, a fusion of original thought and respect for the stories of the past. Dante’s journey through it, however, is his own – and it’s that journey through fire and ice that we’ll study for the next few weeks!