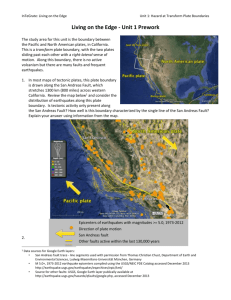

Segments of the San Andreas Fault

advertisement

The San Andreas Fault Team 2 UseIT Intern Class of 2014 Thanh-Nhan Le, Mark Krant, Krista McPherson, Rachel Hausmann , Rory Norman, and Krystel Rios Strike-Slip Only? Thanh Le San Andreas Fault (SAF) What is the San Andreas Fault? • SAF is a system of segmented faults that goes across California • The most famous fault in the world • About 800 miles (1300 km) long • About 28 million years old • Between the Pacific and North American Plate • Discovered after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake • Known as a right lateral transform fault San Andreas Fault (SAF) What are faults? • Faults can be classified in three main directions: Strike-slip, thrust, and normal. • Strike-Slip Fault: Also known as transform fault in which the motions move horizontal and parallel to the fault. San Andreas Fault (SAF) Thrust Fault: When the hanging wall moves over the footwall in an angle that is less than 45ᵒ. • Normal Fault: Occurs when the hanging wall drops below the footwall, so they move away from each other. San Andreas Fault (SAF) • Factors show that SAF does not only consist of strike-slip faults. • The Big Bend starts from Garlock fault shows the complexities of different faulting in Southern California. References Cited • • • • Popov, Anton.,Sobolev, S., Zoback, M. “Modeling evolution of the San Andreas Fault system in northern and central California.” AGU and the Geochemical Society. Web: https://pangea.stanford.edu/researchgroups/stress/sites/default/files/Popov,%20Sobolv%2 0and%20Zback%202012.pdf, August 2012. Fuis, Gary., Scheirer,D.,Langenheim, V., Kohler, M. “A New Perspective on the Geometry of the San Andreas Fault in Southern California and Its Relationship to Lithospheric Structure.” Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. Web: http://seismosoc.org/society/press_releases/BSSA_102-1_Fuise_t_al.pdf, February 2012. Irwin, William. “ Geology and Plate-Tectonic Development.”Web: http://www.pmc.ucsc.edu/~crowe/S109/readings/Irwin%2090%20SanAndreas.pdf Zoback, M.,Lou M., Mount V., Suppe J., Eaton J.,Healy J., Oppenheimer .,Reasenberg P.,John L.,Raleigh B., Wong I., Scotti O., Wentworth C. “New Evidence on the State of Stress of the San Andreas Fault System.” Web:http://seismo.berkeley.edu/~rallen/teaching/S04_SanAndreas/Resources/Zobacketal19 87.pdf, February 2004. The Big Bend Mark Krant What is the Big Bend? • Stretch of the San Andreas Fault beginning near the Garlock fault and continuing to the San Bernardino Mountains • Despite the majority of the San Andreas Fault pointing in the North West direction, the Big Bend flattens out and points more towards the West than any other part of the fault Why is it important? • Along the majority of the San Andreas Fault, the North American and Pacific plate scrape past each other in near perfect right-lateral movement • The Big Bend disrupts the right-lateral movement of the Pacific and North American plates • The plates crash into each other, creating compression and tension http://geology.campus.ad.csulb.edu/people/bperry/geology303/geol303chapter5.html Faults • Tension causes the rocks within the earth’s crust to fracture, creating numerous thrust and strike-slip faults in the area • Sierra Madre Fault – reverse • San Gabriel Fault – right lateral strike-slip http://www.earthquakecountry.info/roots/image11829-1791.html http://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~simkat/geol345_files/bigbend_step.jpg Transverse ranges • Compression forces caused by the Big Bend form the Transverse Ranges San Bernardino Mountains San Gabriel Mountains http://www.tripadvisor.com/LocationPhotos-g33009San_Bernardino_California.html http://www.csupomona.edu/~marshall/research/san.gab.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Bernardino_Mountains#mediaviewer/File:Wpdms_shdrlfi0 20l_san_bernardino_mountains.jpg References • • • • • Singer, E., “The San Andreas Fault System.” The San Diego State University: http://www.sci.sdsu.edu/salton/San%20AndreasFaultSyst.html Zachariasen , J., 2012, “Earthquake Chronology on the Big Bend Segment of the San Andreas Fault: Filling a Gap Towards a Better-Constrained Rupture Scenarios.” U.S. Geological Survey: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/research/external/reports/G08AP00014.pdf, April 2012 Eberhart- Phillips, Lisowski, Zoback, 1990, “Crustal Strain Near the big Bend of the San Andreas Fault: Analysis of the Los Padres-Tehachapi Trilateration Networks, California.” University of Nebraska-Lincoln: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1469&context=us gsstaffpub “The ‘Big Bend’ of California's San Andreas fault.” Southern California Earthquake Center: http://www.scec.org/education/public/allfacts.html “Southern California Faults.” Putting down roots in earthquake country : http://www.earthquakecountry.info/roots/socal-faults.html Segments of the San Andreas Fault Krista McPherson University of Southern California Southern California Earthquake Center UseIT 2014 Intern Why is this important to study? The San Andreas is not one fault, but a complicated system of faults Breaking down the San Andreas allows us to look at the interfaces between segments Help us understand future earthquakes Segmentation of the San Andreas Can be divided into three sections: • Northern • Central • Southern Southern Segment MAJOR EARTHQUAKES: • 1680 Earthquake • Magnitude: 7.7 Mw • 1812 Wrightwood Earthquake • Magnitude: 7.5 Mw • 1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake • Magnitude: 7.9 Mw http://geology.com/earthquake/california.shtml#fort-tejon Shake Map of Fort Tejon Earthquake Northern Segment MAJOR EARTHQUAKES: • 1906 San Francisco • Magnitude: 7.8 Mw • Began directly off the coast of San Francisco Why did none of these major earthquakes rupture the entire length of the fault? http://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/nca/1906/shakemap/ Shake Map of San Francisco Earthquake Central Segment (Creeping section) • Occurs between Cholame Valley and San Juan Bautista • Slip rate of 28mm/yr • Prevents the San Andreas from rupturing all the way through • The presence of serpentinite and talc allows for constant slipping http://www.geology.neab.net/minerals/serpenti.htm Serpentinite http://www.johnbetts-fineminerals.com/jhbny Lizardite http://www.beg.utexas.edu/mainweb/publications/graphics/talc400 Talc Sources • • • • • • • • • Bennett, R.A., Friedrich, A.M., and Furlong, K.P. 2004. Codependent histories of the San Andreas and San Jacinto fault zones from inversion of fault displacement rates. Geology 2004; 32; 961964. doi: 10.1130/G20806.1 Jacoby, G.C. Jr., Sheppard, P.R., and Sieh, K.E. (1988). Irregular Recurrance of Large Earthquakes Along the San Andreas Fault: Evidence from Trees. Science, Vol. 241, No. 4862, pp. 196-199. Lomax, A. 2006. Location of the Focal Region and Hypocenter of the California Earthquake of April 18, 1906. March, 2006. Meisling, K.E., Sieh, K.E. 1980. Disturbance of Trees by the 1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake, California. Journal of Geophysical Research. Vol. 85. No. B6. Pages 3225-3238. June 10, 1980. Moore, D.E., Rymer, M.J. 2007. Talc-bearing serpentinite and the creeping section of the San Andreas Fault. Nature 448, 795-797. 16 August 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature06064. Schleicher, A.M., van der Pluijm, B.A., and Warr, L.N. 2010. Nanocoatings of clay and creep of the San Andreas Fault at Parkfield, California. Geology 2010; 38;667-670. Doi: 10.1130/G31091.1 Sieh, K., Stuiver, M. and Brillinger, D. (1989). A More Precise Chronology of Earthquakes produced by the San Andreas Fault in Southern California. Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 94, No. B1, pp. 603-623. Thatcher, W. 1975. Strain Accumulation and Release Mechanism of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research. December 10, 1975. Vol. 80. No. 35. Townley, Sidney D. (1939). Earthquakes in California, 1769 to 1928. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 21-252. Mini Grand Challenge #1 Team 2 Rachel B Hausmann Oregon State University College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences University of Southern California Southern California Earthquake Center Summer 2014 SCEC UseIT Intern What is a recurrence interval? Recurrence Interval = Average slip per major rupture / Slip Rate Earthquake Aka: the frequency of a certain seismic event Avg. slip rate (mm/year) Seismic Condition Last major earthquakes Displacement (m) Northern 35 mm/year Locked 1906 San Francisco 7.8M 3 - 4.5 m Central 28 mm/year Aseismic creep 2004 Parkfield 6.0M 0.58 m (max) Southern 35 mm/year Locked 1857 Fort Tejon 7.9M 9m Complex fault geometries of the Southern and Northern allow for large earthquakes (Li and Liu, 2006). And this is how we know… Plate motion measurements using geodic data!! Motion Magnitude Intensity Citations Abaimov, S.G., Turcotte, D.L., and Rundle, J.B., 2007, Recurrence-time and requency slip statistics of slip events on the creeping section of the San Andreas fault in central California, Geophysics Journal International. Vol. 170, p. 1289Fialko, Y, 2006, Interseismic strain accumulation and the earthquake potential on the southern San Andreas Fault system, Nature. vol. 441, p. 968- 971 Shelly, D., 2010, Periodic, Chaotic, and Doubled Earthquake Recurrence Intervals on the Deep San Andreas Fault, Science. vol. 328, p. 1385-1388 Shelly, D.R., and Johnson, K.M., 2011, Tremor reveals stress shadowing, deep postseismic creep, and depth dependent slip recurrence on the lower crustal San Andreas fault near Parkfield, Geophysical Research Letters. vol. 38, p. 13312-13318 Sieh, Kerry E., 1978, Slip Along the San Andreas Fault Associated with the Great 1957 Earthquake, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. vol. 68, No. 5, p. 1421-1448 Stock, J.M., and Lee, J., 1994, Do microplates in subduction zones leave a geological record? Tectonics. vol. 13, p. 1472-1487 Wallace, R.E., 1970, Earthquake Recurrence Intervals on the San Andreas Fault, Geological Society of America Bulletin. vol. 81, p. 2875-2890 Zachariasen, J., 2008, Detailed Mapping of the Northern San Andreas Fault Using LiDAR Imagery, United States Geological Survey. Final Technical Report, p. 1-47 Zielke, O., et al, 2010, Slip in the 1857 and earlier large earthquakes along the Carrizo Plain, San Andreas Fault, Science Magazine. vol 327, p. 1119-1121 San Gorgonio pass The San Andreas traffic jam • The San Andreas rarely contains discontinuity. • In between this split are many faults, a feature uncharacteristic of the San Andreas fault line. Southeast Coachella Valley Southern San Bernardino Mts. Banning Fault • Many parts of Banning Fault are dead • Tendency to transfer slip to Garnet Hill fault. SOURCES • Allen, Clarence Roderic (1954) The San Andreas Fault Zone in San Gorgonio Pass, California. Dissertation (Ph.D.), California Institute of Technology. • J.C. Matti, U.S. Geological Survey, December, 1979. http://geomaps.wr.usgs.gov/archive/scamp/html/dec79p4_ 34M.html • Sieh, K., Slip along the San Andreas fault associated with the great 1857earthquake, Seismol. Soc. Am. Bull., 68, 1421– 1428, 1978. • Tucker, Carol, 1992 “Landers Earthquake Added Stress to San Andreas” USC News http://www.usc.edu/uscnews/stories/68.html December 1992. SOURCES (cont.) • Sieh, K., and J. C. Matti, The San Andreas fault system between Palm Springs and Palmdale, southern California: Field trip guidebook, in Earthquake Geology San Andreas Fault System Palm Springs to Palmdale, pp. 1– 12, Assoc. of Eng. Geol., South. Calif. Sec., 1992 • Clark, M., Map showing recently active breaks along the San Andreas fault and associated faults between the Salton Sea and Whitewater River-Mission Creek, California, Misc. Geol. Invest. Map, I-1483, U.S. Geol. Surv., Boulder, Colo., 1984. By Krystel Rios East Los Angeles College – Civil Engineering, Geology THE SALTON TROUGH WHERE IS THE SALTON TROUGH LOCATED? WHAT IS THE SALTON TROUGH? Basin: Large low-elevation area, common for sediments to collect here. Example of a “Graben”. Associated with pull apart centers and bound by parallel faulting. This sinking is called subsidence. HOW HAVE EXTENSIONAL FORCES CAUSED THE FORMATION OF THE TROUGH? Extensional Forces: Increase the distance between two points, or pulls them apart. In our case rock is being pulled apart alleviating pressure on the crust. TWO MAIN CULPRITS Brawley Spreading Center Spreading Center at Cerro Prieto Thermal Fields Strong evidence of this spreading and rifting is presented by strong geothermal activity in these centers. So much at the Cerro Prieto that Thermal plants for energy collection are stationed here. These two spreading centers are connected and accommodated by The San Andreas, Imperial, and Cerro Prieto Faults. MORE COMPLICATIONS? Works Cited • Barker E. Charles (2000) Salton Trough Province • Gleick, P. H. (2003). Global Freshwater Resources: Soft-Path Solutions for the 21st Century. Science, 302(Nov. 28), 1524-1528. • Hough, Elizabeth Susan (2004). Finding Fault in California • Jenning, S., and Thompson, G. R. (1986). Diagensis of Plio-Pleistocene sediments of the Colorado River Delta, southern California. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 56(1), 89-98. • Lizarralde, D., et al. (2007). Variation in styles of rifting in the Gulf of California. Nature, 448(July 26), 466-469. (doi:10.1038/nature06035) • Sykes, G. (1937). The Colorado River Delta. American Geographical Society Special Publication, no. 19. American Geographical Society: New York. • Winker, C. D., and Kidwell, S. M. (1986). Paleocurrent evidence for lateral displacement of the Pliocene Colorado River Delta by the San Andreas fault system, southeastern California. Geology, 14(9), 788-791. • Geology of the Imperial Valley, California, a Monograph by Eugene Singer http://fire.biol.wwu.edu/trent/alles/SingerImperialValley.pdf • Geology of the Salton Trough Edited by edited by David L. Alles. (2011) Western Washington University