Blanca Moreno-Dodson - Tax Coop | CONFERENCE

advertisement

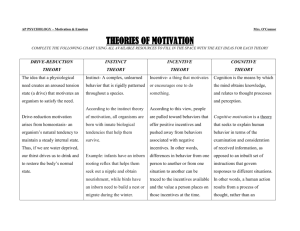

From Tax Competition to Tax Harmonization: Challenges for Developing Countries WORLD BANK GROUP BLANCA MORENO-DODSON LEAD ECONOMIST, TAX POLICY OCTOBER, 2015 Introduction Grateful to be here Honored to represent the WBG tax team Using background materials from joint IMF-OECD-UN-WBG Paper on Tax Incentives and WB materials (Awasthi, James, Stern) Presenting lessons from WBG regional and global work on tax integration and harmonization Focus on effects of tax competition in developing countries and ideas for possible solutions Open to your inputs for further analysis and operational work Tax Competition: Background Given increasing interdependence among countries in a globalized world, capital mobility puts pressure on corporate income tax rates Countries lower their income taxes (uniformly or through special advantages) in order to attract business It also creates competition for taxing rights, i.e. competition for having profits reported in a particular country, without any associated movement of production “Interdependence of tax setting authorities” has been demonstrated empirically (Devreux et al.) Process remains unclear Increased economic integration (trade liberalization) has increased the effects of corporate income taxation on investments (Persson and Tabellini) Global Tax Competition Affects Developing Countries It creates pressure to reduce tax burdens on investors Developing countries want to avoid losing FDI and jobs to other countries Investors often request specific provision and application of tax incentives: adds an element of unfairness and discretion Tax incentives are often used without assessing their possible effects: when adopted in one country, they might evoke strategic reactions in other countries to adopt the same policies The risk that, ultimately, all countries will lose, threats developing countries By attracting investment that would otherwise have gone to another—e.g. neighboring—country, tax incentives can cause (unknown) adverse cross-border spillover effects on the welfare of other countries Global Tax Competition Affects Developing Countries Negatively While in developed countries corporate tax reform has been revenue neutral due to tax reduction coupled with tax base expansion, the later has not materialized in the poorest and most vulnerable developing countries (Keen and Simone) Structural problems remain (below tax revenue potential due to socioeconomic characteristics) but the “race to the bottom” (reduction of statutory rates and expansion of tax incentives) and tax rights competition (inadequate definition of permanent establishments) are eroding tax bases in the developing world The Net Social Benefit of Tax Incentives is often not measured The effects on FDI are hard to disentangle Other benefits depend on how FDI has affected: Job creation Displacement effects Domestic investment Productivity spillovers Public costs should be measured by the net revenue loss for the government—direct costs valued at the marginal cost of public funds Indirect costs are associated with discretion and lack of transparency Effects of Tax Incentives on FDI Tax incentives tend to be rather ineffective in attracting FDI that is: resource seeking (to exploit the presence of natural resources), market seeking (to penetrate a local market), strategic asset seeking (to exploit local know-how or technology) They are more effective in promoting efficiency seeking FDI: to exploit cost advantages in production for the world market and promote exports (Grubert and Mutti, 2004) Business agglomerations attract FDI due to very favorable production conditions, irrespective of the level of taxation (Baldwin and Krugman, 2004) When investment conditions are unfavorable due to poor infrastructure and weak governance, tax incentives have little relevance to location choice (James and Van Parys, 2010) Examples of Tax Incentives in Developing Countries Evidence for 40 Latin American, Caribbean and African countries: The length of tax holidays systematically increased FDI inflows during 1985-2004 These FDI inflows did not come along with an increase in total domestic investment, nor did they promote economic growth, suggesting crowding out of domestic by foreign capital (Klemm and Van Parys, 2012) Evidence of significant displacement effects of domestic investment by FDI in Latin America Displacement is less prevalent in Asia and Africa (Agosin and Mayer, 2005) From Tax Competition to Tax Harmonization: Regional and Global Developing countries can start by cooperating at the regional level in order to: Minimize regional harmful tax competition with the goal to mobilize domestic revenues Explore potential for more regional investment as tax systems are harmonized Adopt a regional policy on tax incentives to prevent revenue losses by all Exchange information regionally in order to trigger adoption of best practices At the global level, improved tax coordination can create further potential for revenue generation through: Harmonizing transfer pricing legislation and techniques Improving bilateral tax treaties (multilateral) and prevent tax treaty abuse Upgrading tax administration capacities to enforce rules and audit international tax transactions (brings more certainty) Regional Experience: East African Community Tax competition: EAC decided on a positive list of agreed upon fiscal incentive instruments Tax expenditures to be carried out every year and shared among the 5 member countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi) Provision of incentives to follow guidance set by EAC as well as monitoring system International Tax issues EAC to agree on set of acceptable calculation methods for transfer pricing cases, as well as definitions of goods and services (for comparables) Tribunal to be set up to settle within-region TP disputes Agreement on systematic exchange of tax information within the region Regional Experience: Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Tax competition: CARICOM Agreement on the Harmonization of Tax Incentives to Industry (1973) Highly detailed, including (i) time limits; (ii) classification of enterprises in terms of “value added”; (iii) control and reporting obligations by the administrations responsible for the application of incentives in each member state;(iv) specifies reduction of income tax that may be granted by type of activity Agreement lacked penalties in the event of non-compliance: little effort on making adjustments, affecting overall compliance. Text is ineffective today, illustrating the pitfalls of an overly-ambitious agenda International Tax issues A survey on transfer pricing was prepared and is periodically updated to share information among countries with a view to improving the use of best practices as well as to support CARICOM’s efforts towards more harmonization Suggested Areas for Harmonization/Potential Risks Areas for Harmonization Corporate income tax systems (avoid large discrepancies) VAT tax bases and thresholds (not identical rates needed) MSMEs regimes Potential Risks Expectations for greater regional integration can be too high and not aligned with implementation realities If all partners don’t participate and adopt rules and principles, it could split the bloc into different groups Heterogeneity in levels of industrialization and development requires careful consideration to the extent and timetable of harmonization What is Next? Despite difficulties to harmonize tax regimes regionally and globally, persistent market failures and asymmetry of information in developing countries require coordinated action: Market competition alone will not generate tax rates convergence and an efficient allocation of resources across countries Efforts must continue to intensify and simplify regional/global tax coordination and harmonization to prevent a “race to the bottom” in developing countries, as well as to adapt methods in international taxation which better capture national production and profits Developing countries cannot do it alone (individually or regionally) The opposite could result in stagnant tax revenues, more fiscal instability (as needs for public goods remain great in developing countries) and more dependence on foreign aid (limited and volatile), further contributing to aggravate per capita growth imbalances and income disparities at the global level The DRM Agenda to reach the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals will be supported by a new Tax Policy Framework (WB-IMF) in support of these global efforts