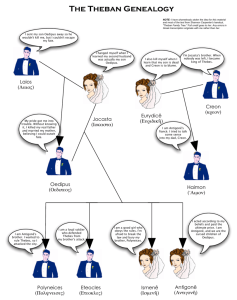

The Theban Saga

advertisement

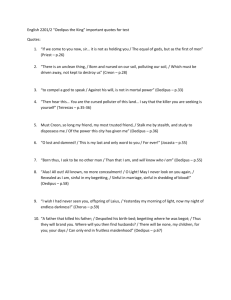

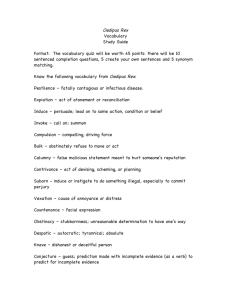

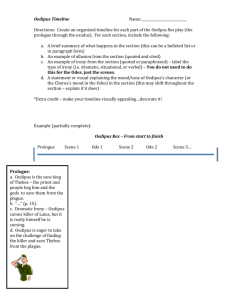

The Theban Saga Hero Stories, A Strange City, A Very Close Family Myth, legend, saga and folktale Modern scholars use these terms to distinguish the subject matter of traditional stories: Myth means stories which focus on the gods, their works, and their connections with humans. Legend and saga focus on human history: the stories of the great heroes, and civic history. Folktales are typically popular stories which focus on character types (e.g. “the foolish boy” “the youngest daughter”) and are regarded as stories only. We use these terms, but the Greeks did not, though they would judge some stories serious and some frivolous. Myth, legend, saga and folktale Greek hero tales cross the line between myth and saga, because so often the gods are directly involved with founding the heroic line and guiding the heroes’ destinies. “Mythic” heroes like Oedipus, Orestes and Heracles were regarded as historical figures, who lived in a time when men and gods were closer. Many Greeks (for example, Herodotus) recognized the fantastic elements of these stories and tried to rationalize them, while still regarding the heroes themselves as real. Greek heroes often share story elements with folktale heroes, but have strong connection with history and sacred practice. Motifs and Archetypes The psychologist Carl Jung proposed that in addition to our individual unconscious minds, there is a “collective unconscious,” an underpinning of ideas and images we share by virtue of sharing the human experience. Archetypes are images, story patterns, and connections that reflect the collective unconscious. Consequently they show up in many variants, all over the world. Vladimir Propp studied Russian folk tales and identified important motifs and shared structures between many different tales. Motifs are story elements or functions: “the characters may change, but the functions do not.” Hero Tales Many scholars have observed that the heroes of myth share some important characteristics: Extraordinary birth and childhood •virgin birth (Jesus), divine parentage (most Greek heroes) He faces opposition from the beginning •Oedipus is left to die, Herakles must serve his cousin, Perseus & Moses are set afloat as infants His enemies instigate his achievement •Jason’s cruel uncle sends him for the golden fleece, Heracles’ cruel cousin sends him on the Labors Hero Stories He is helped by at least one ally, often divine •Usually Athena, in Greek myth He faces apparently insurmountable obstacles, often pursuing a Quest •Heracles’ 12 labors, getting the golden fleece (Jason) or Medusa’s head (Perseus) In his quests, he faces conflicts with often supernatural forces that challenge him in essential human realms: spiritual, mental, sexual, physical. •Gilgamesh must deal with Ishtar’s advances and the monster Humbaba; Oedipus outwits the Sphinx, Jesus faces down Satan’s temptations, Heracles goes to Hades . . . Hero Stories He may have to observe taboos •Orpheus can’t look back at Eurydice He faces death or a metaphorical underworld journey •Heracles, Theseus, Orpheus and Odysseus go to the underworld; Jesus experiences death, Gilgamesh & other heroes go to the ends of the earth or into lonely desperate trials At the end of his quest, he may be rewarded, or through his suffering he may have brought benefit to his community •Herakles betters the world, and his death is transformed into immortality, Gilgamesh becomes a better king, Jesus is resurrected and brings the hope of resurrection Hero Stories How universal are these stories? Scholars disagree. Some issues: •Sometimes stories from other societies are not understood properly, and aboriginal styles of tale telling can be mis-translated or mis-told to reflect familiar story patterns (often a complaint with Native American stories). •Even similar motifs may have different specific meanings for different peoples; similar figures (for example, the owl) may have a similar range of meanings but different values (positive or negative, scary or not, relevance in other tales). •In each society, individuals tell stories differently. Heroine Stories What about Heroines? Greek society has a patriarchal structure and genderbased division of labor, so quest stories tend to focus on male figures (who may travel, fight and adventure in the culture’s schema) Because of our prejudice towards written, narrative sources, we often overlook heroine stories that might be told in different ways, for different purposes. (In other words, if the hero stories are entertaining tales, and the heroine stories are told in a spare format associated with sacred practice – we will ignore the heroine stories!) Heroine Stories There tends to be more variation in heroine stories. Typical in many stories is a rape or kidnapping, possibly metaphorically recreating the central “rite of passage” in women’s lives: marriage and leaving her birth family. Many heroines endure great suffering as young women and young mothers, finally becoming the “founding mother” of a new city or society through a heroic son. Some heroines exist in part or in whole as a counterpoint of a hero story: Ariadne to Theseus, Medea to Jason. Yet often these heroines have an independent place in religious cult and ideology. The Theban Saga Thebes is one of the oldest cities of Greece, site of a vast Mycenaean palace, and powerful well into the Classical period. In Greek drama (most of which was written in Athens) Thebes appears as a strange, dangerous city where anything can happen: Dragon-born warriors, Maenads, Man-eating sphinxes, Incestuous marriages and who knows what else? The Founding of Thebes Most cities have complex foundation legends that probably say something about the inhabitants’ views of their role in cosmic and national history, and their civic identity and values. Like many such stories, Thebes’ foundation begins with an abduction story . . . Europa and the Bull. The Founding of Thebes Zeus was attracted to Europa, a young girl from Tyre in Asia Minor. He appeared to her as a bull. When she got on his back, he took her across the sea to Crete. Europe was named after her. Her brother Cadmus went looking for her. He consulted Apollo at Delphi. Apollo told him to forget Europa, and follow a certain cow . . . The Founding of Thebes Cadmus followed the cow till it stopped, then prepared to sacrifice it. When his men went to get water from a nearby spring, they were killed by the serpent who guarded it. Cadmus killed the serpent. Cadmus sowed the serpent’s teeth to grow new warrior companions. They killed each other, leaving five who became the founders of Thebes’ main families. The Founding of Thebes Then Cadmus had to serve Ares, the serpent’s master, for a year. Afterwards he married Harmonia, daughter of Ares and Aphrodite. Among their descendants: Semele, Dionysus, & Pentheus. They ruled for a long time and were finally transformed into serpents – a connection of Thebes and chthonic powers? Four generations later came Oedipus. Harmonia as dragon-beseiged maiden Oedipus: Sources Our best source for the Oedipus story is Sophocles, an Athenian tragedian who wrote three plays on the theme from 444 – 404 BCE: Oedipus the King (Oedipus Rex) tells of how Oedipus discovered how he had fallen into horrible crimes just as he tried to avoid them; Oedipus at Colonus tells how he died in exile; Antigone tells how his daughter and most of his family are destroyed in the aftermath of still more family crimes. Sophocles Oedipus: Sources Aeschylus is the author of Seven Against Thebes, which details the war between Oedipus’ two sons. Ovid tells anecdotes from the life of Tiresias, and other authors fill in the blanks. Art shows several scenes of note from the tale: notably, Oedipus and the sphinx. Oedipus Oedipus’ father, Laius, was cursed because he kidnapped the young son of his host Pelops, a violation of hospitality. Later, the Delphic oracle told him: I will give you a son, but you are destined to die at his hands. This is the decision of Zeus. When Laius and his wife Jocasta had a son, they exposed him to die, after piercing his feet. But the slave to whom they entrusted the task had mercy and didn’t do it. The young son, called Oedipus (“Pierced feet”), was raised as the son of the king and queen of Corinth. Oedipus Later Oedipus also went to Delphi, after a companion taunted him that he wasn’t his parents’ true son. The oracle told him: You are fated to couple Horrified, Oedipus left Corinth with your mother, you will to take himself far away from his bring a breed of children supposed parents. into the light that no man can bear to see – you will At a crossroads near Delphi, he kill your father, the one met an arrogant old man and his who gave you life! entourage. The driver shouldered me aside – I struck him in anger! And the old man brought down his two-pronged prod straight at my head! I paid him back with interest – killed them, every one. Oedipus Proceeding on his way, Oedipus came to Thebes, which was under attack by a terrible monster, the sphinx. The sphinx would kill all passers-by who couldn’t answer her riddle: What walks on four legs in the morning, Two legs in the afternoon, And three legs in the evening? Oedipus was the only one to answer her question correctly: M A N Oedipus Tyrannus Oedipus entered Thebes as a hero. He married the recentlywidowed queen and became king. He and Jocasta had four beautiful children: twin boys and two girls. Then came a plague. At the Thebans’ urgent request, Delphi tells them why: Relief from the plague can Oedipus calls on Tiresias to only come one way: uncover the murderers. Uncover the murderers of Tiresias is at first reluctant, Laius, put them to death then, provoked, announces: or drive them into exile. From this day onward, speak to no one, not the citizens, not myself! You are the curse, the corruption of the land! Oedipus is enraged, suspecting treachery. But he pursues the truth. Oedipus Tyrannus Through Oedipus’ relentless inquiry, all the pieces fall into place: He discovers from a servant that he was adopted, then that he was sent from Thebes as an infant. Jocasta figures it out a moment before he does, and goes off to commit suicide. Finally Oedipus realizes: Oedipus blinds himself and goes into exile. O light! May this be the last time I look upon you! I was born from one who should not have born me, lived with those I shouldn’t have lived with, and killed those I should not have killed! Oedipus at Colonus Oedipus Tyrannus ends with Oedipus physically blind, but finally “seeing” the horrible truths of his life. Count no man happy until he reaches the end of his life without suffering! Oedipus goes into exile with his young daughters, Antigone and Ismene, to lead him. Oedipus at Colonus Sophocles wrote Oedipus at Colonus near the end of his life and it was published after his death. Oedipus is now shunned and hated because of his horrible crimes, and he struggles with one of life’s great injustices: Know that I was the sufferer of my deeds, not the agent. This is why you are afraid of me. How was I evil in nature? I have come to this point not knowing what I did. I suffered and was destroyed by those who knew (i.e., the gods). With his daughters, Oedipus takes refuge in a sanctuary of the Furies (Eumenides) near Athens. Oedipus at Colonus A prophecy has said that Oedipus’ bones will strengthen the city where they are buried. So two contingents try to get him back to Thebes: •Creon, Jocasta’s brother, who still scorns him, •Polynices, his own son, who is now planning to attack Thebes since he too has been exiled (more later) The Athenian king Theseus protects Oedipus and his daughters. Finally a mysterious voice calls Oedipus away, and he vanishes into the earth – his bones will remain at Colonus and strengthen Athens. Seven Against Thebes Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes continues the story. After Oedipus went into exile, he left his kingdom in the hands of his twin sons, Eteocles and Polynices. Eteocles would rule one year, Polynices the next. But Eteocles refused to give up his rule, and Polynices decided to commit the horrible attach to attacking his own city. He gathered 6 heroes to help him – seven commanders to lead the attack on Thebes’ seven gates. The attack fails, and all but one of the commanders are killed. Polynices and Eteocles kill each other in single combat, adding to the family’s self-destruction. Antigone Sophocles’ Antigone, actually the earliest of his Theban plays, completes the story. After the destruction of the twin brothers, Creon becomes king of Thebes. He orders for Eteocles, the defender, to be buried in state, and Polynices, the attacker, to be left unburied for the birds and dogs, with a death penalty for anyone caught violating the law. Antigone refuses to leave her brother unburied, and after two attempts to bury him, is caught and sentenced to death. Antigone Creon: Did you dare to break these laws? Antigone: Yes, for it was not Zeus who gave me this decree, nor did Justice, the companions of the gods below, define such laws for human beings. Nor did I think your decrees were so strong that you, a mortal man, could overrule the unwritten and unshaken laws of the gods. Antigone raises complex issues about justice: divine vs. human, family vs. society, personal values vs. abstract ideals. It also explores other fundamental conflicts: male vs. female, weak vs. strong, authorities vs. outcasts. Antigone Antigone ends tragically. Although Antigone is his niece and the fiancee of his own son, Creon orders her to be buried alive, a fit punishment in his eyes. But Tiresias appears to tell Creon he should not execute Antigone. Finally persuaded, Creon rushes to unseal the tomb. Antigone But it is too late. Antigone, deciding not to wait for a slow death, has already killed herself. Creon’s son commits suicide in despair, and Creon’s wife does the same. Left alone, Creon contemplates the ruins of his family, in the wake of his attempts to enforce justice his way. Tragedy & Oedipus Greek theater brought out many complex ideas in an emotional context. Their complex world view was carried out in ideas of fate, hubris and hamartia. Tragedy & Oedipus Tragedies often spurred serious discussions among theater attendees. Some issues for us: Hubris – blind arrogance – often sets off a chain of events that leads to destruction. Was hubris a factor for any of the protagonists in the Theban Saga? Tragedy & Oedipus Hamartia – a tragic flaw – is often a blind spot, a personality feature, or even just a chance deed that causes disaster for a character. Is this a factor in the Theban saga? Tragedy & Oedipus Miasma, or pollution, follows Oedipus despite his moral blameworthiness – how can humans deal with the inevitable consequences of even accidental actions? Tragedy & Oedipus And what is the role of Fate: did any of the characters have a chance against the fate the gods had planned for them? If not, what was the purpose of their sufferings? finis