Seminar in Public Policy Analysis - California State University, Long

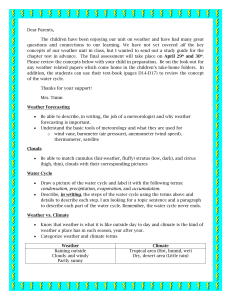

advertisement