The Social Construction of the American Democracy: A Study

advertisement

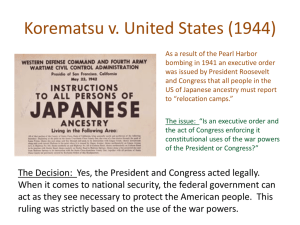

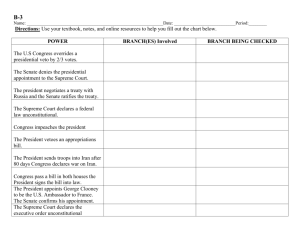

The Social Construction of the American Democracy: A Study Through a CMM Lens Chelsea Johnson Johns2cc@dukes.jmu.edu James Madison University SCOM 432 Final Paper Dr. Leppington 1 Abstract The United States Constitution establishes three separate branches of the government; the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. This paper will undertake to look at the relationship between the judiciary (specifically the U.S. Supreme Court) and the legislative (specifically Congress); and particularly the focus will be on the inherent conflict between the two branches of government. A series of three different bill’s Congress put forth and the rejection of two of them in Supreme Court cases will be used to display the “back and forth” process to find a resolution. Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union (Dealing with Congress’s first bill the Communications Decency Act of 1996) is the first case to be taken; then Congress revises it and comes back with the Children’s Online Protection Act (COPA) in Ashcroft vs. American Civil Liberties Union. Following the Supreme Court finding that act unconstitutional Congress again comes back and proposes another revision names the Children’s Internet Protection Act, which the court finally upholds in United States vs. American Library Association. This “back and forth” process between the Supreme Court and Congress begs the question of how is our democracy socially constructed? In addition, how is this conflict an integral part of the social construction of our social reality? Lastly, along with these questions I will establish through example how the system self-organizes. This paper will provide not only the answers to the previously mentioned questions, but will also expand upon the process between Congress and the Supreme Court. 2 Introduction and Historical Background Beginning from the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution there has been an inherent conflict relationship between the judicial and legislative branches of the government. In Article I of the U.S. Constitution the Framers established the legislative branch (Congress), as well as the Judicial Branch in Article III of the Constitution. In the each of these Articles it was laid out the rights and boundaries for each branch. In order to ensure this system of boundaries, a “checks and balances” system was put into place. One must remember the time in which the U.S. Constitution was written, it was one where there was a fear of a strong centralized government, and these checks each branch has on one another was and continues to be of significant importance. This examination will look specifically at a “back and forth” conversation between the Judicial Branch (for the purpose of this case The Supreme Court) and the Congress. This interaction and processing of one another’s hierarchy’s of meaning will be shown through the process of three acts of Congress and the subsequent Supreme Court cases that go along with them either accepting it as constitutional or declaring it to be unconstitutional. It is the examination of this process that will illuminate how democracy is socially constructed as well as how this conflict relationship is such an integral part of our social reality. Necessary to understanding the beginnings of the relationship between Congress and the Courts, one can refer to Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist 78, published in March of 1788 (just before the Constitution was ratified in June of 1788). Federalist 78 was mainly focused on the judicial branch, pointing out that the Framers at this time viewed the courts as the least powerful branch of government established; essentially claiming that they had no “real” power. Hamilton specifically says “…the Legislature not only commands the purse, but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The Judiciary on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse, no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society and can take no active resolution…It may truly be said to have neither Force nor Will, but merely judgment…” (Hamilton, 1788, pg. 472). It is interpreted from this that there was 3 little confidence in the court system as actually being an equal member of the three branches of government. Yet, the process of which is being presented in this study will give insight into how the process changed this belief and formed the equal (if not slightly more powerful) Supreme Court that is characteristic of the current Democracy. The assumption of the Founding Fathers was wrong, the Court may merely have judgment but it is the process behind the judgment and the meaning of it that creates the conflict necessary for social construction. The process of the “back and forth” communication between Congress and the Court has constructed the judicial to become more equal in the system, which ultimately wields to a stronger checks and balances system. In this system, Congress forms laws and bills meant to be in the best interest of the citizens, yet they might not always be able to pass the first time being proposed. By this meaning the Court must be there to not only decide cases that come before them in terms of the Constitution, but also interpret the federal law and ensure there is no breach of the Constitution present. This particular case will look at three acts of Congress which are as follows: First the Communications Decency Act of 1996 (CDA), the Child Online Protection Act in 1998 (COPA), and lastly the Children’s Internet Protection Act in 2001 (CIPA). As well as the corresponding court cases that arise from the acts of Congress (which together establish this episode of communication) that are as follows: First Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union challenging the Communications Decency Act, second comes Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union challenging Congresses next attempt, the Child Online Protection Act, and lastly the study will look at United States v. American Library Association challenging the Children’s Internet Protection Act. In order to fulfill this study and understand the process that is being discussed, one must also understand the Coordinated Management of Meaning Theory (CMM). CMM is the process this study uses to illuminate the relationship and effects of the relationship between Congress and the Supreme Court. CMM is a theory that views communication as a two-sided process of coordinating actions with others as well as making and managing meanings in relation to others. To describe the process one goes through in constructing their social worlds CMM identifies three main aspects; first 4 coherent, second coordination, and third mystery together creating story’s that create ones social reality. The first, coherence, describes how meaning is achieved in conversation, essentially it is in order to interpret the world and ones place in it. Coherence can be thought of as stories and these stories can be even further broken down into six more aspects: content, speech acts, episodes, relationships, self, and culture. Those six aspects will be what forms’ the individuals (or in this case the governmental parties) contextual forces and hierarchy. Secondly, coordination adds that actions are not alone in regards to communication; the words or actions come together to produce the patterns or stories governing the behavior used during interactions. Coordination establishes “rules” in a sense for the communication and it is through this coordination that when speech is governed by different rules communication can still successfully exist. The last of the three basic aspects that make up CMM, mystery, allows one to recognize the “unexpressed stories,” that not everything in communication can be explained. It is through these complex interconnected patterns of CMM that this study will show the social construction of Democracy, as we know it today, within a limited example of the process. Methods and Data The Coordinated Management of Meaning has a certain model that allows one to clearly see all of the interconnected parts of the process working; part of this is called the hierarchy model. Essentially this is a tool that allows one to explore the perspectives of the other party in the conversation as well as taking a more thorough look at their parties own perspectives and intentions. This study uses the hierarchy model along with the serpentine model in order to portray the conversation between Congress and the Supreme Court. The serpentine model takes the hierarchy model a step further in highlighting the importance of the interaction and adding in some sense of time to the pattern. This 5 extended model is being used because it is important in the social construction of reality to stress the understanding of the pre-figurative forces (previous events) and their impact to form the current episode being interpreted. Through use of the serpentine it will also make it significantly easier to understand and follow the “back and forth” interaction between Congress’ s Acts and the decisions issued by the Supreme Court. The United States Congress starts off this examination and relationship, due to the advancement of Internet technology and the greater accessibility to inappropriate material via the Internet Congress felt it their duty to find some way of protecting the youth. Congress’s intentions are to protect the youth of the United States from obscene materials readily available on the Web, in Congress’s hierarchy they view it as they are culturally obligated to protect the members of society who are largely unable to speak for themselves. For Congress the contextual force of self portrayed is that they have been afforded this power to pass legislation in benefit of the citizens so they feel they are going to use it in order to protect the innocence of the youth. As a result of this necessity to protect Congress first passes the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which is the first utterance in the serpentine model. (Refer to Appendix for visual of the serpentine) Congress’s primary intention was the protection of minors, yet that is not what this action was viewed as from other parties standpoints. This law, among many other things, “criminalized the knowing transmission of obscene or indecent messages to any recipient under 18 years of age…that in context depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards…” (O’Brien, 2008 pg.487) Yet, the American Civil Liberties Union does not interpret the intentions of the CDA as a means of protection. Rather, the ACLU views this as a violation to citizen’s fundamental First Amendment Rights. The First Amendment to the Constitution states “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, ...or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” (O’Brien, 2008 pg. 12) As a result of the passing of the CDA, this prompts the American Civil Liberties Union to question whether this allowed or did Congress overstep their boundaries. Implicated in their contextual force, how dare Congress infringe on citizens fundamental 6 rights to free speech. As for the culture aspect of the ACLU, as congress saw it as their duty to protect the youth of the US, the ACLU sees it to be their obligation to protect the fundamental freedoms afforded to every citizen. The ACLU challenged the constitutionality of the Communications Decency Act, it is their job to fight against restrictions on liberty and that is what they did. The lower court ruled and put a preliminary injunction against the CDA. In response Attorney General Janet Reno, who did not view the CDA as an infringement upon individual rights, appealed to the Supreme Court contesting the injunction. This is the second utterance in the process; the appeal to the Court contesting the validity of the CDA and the lower courts ruling. The episodes of each of the players are already forming very different intentions and obligations. The Supreme Court granted a Writ of certiorari, essentially agreeing to hear arguments for the case Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union. If this is a valid appeal the Supreme Court is obligated to uphold the lower courts decision. As will be noticed as the process continues the contextual forces behind the Supreme Court will not really change. The intentional force behind the Court is to interpret federal law and cast judgment upon those cases that come before them. It is in the Courts culture to have a powerful sense of morality grounded in the rule of law and enforcing the principles set forth by the Founding Fathers in the Constitution. The episode of the Court unfolds from no longer being the intention to solely protect individual rights, but it is also now to determine if the Communications Decency Act infringes upon rights afforded by the Constitution or if Congress was indeed within their boundaries of protecting the youth. Ultimately, the Supreme Court decides to uphold the lower courts decision, declaring the Communications Decency Act of 1996 to be invalid and an unconstitutional infringement upon individuals’ fundamental rights in 1997. The Supreme Court is communicating with Congress, establishing a conversation, telling them that although their intentions of protecting the youth may be good the law was too broad and must be revised. Congress interprets this decision as feedback that they must revise the law and make it more narrowly tailored to block certain things on the Internet and limit it so it does not affect all individuals’ free speech rights. As a result, Congress therefore feels compelled to revise the act and form a new one protecting minors form materials deemed harmful on the Internet while still remaining within the confines of the powers afforded 7 to them. Congresses second attempt at regulation comes with the Child Online Protection Act in 1998. This act was never actually signed into law it remained just an act of Congress. Similar to the Communications Decency Act of 1996, COPA “…prohibited any person from knowingly and with knowledge of the character of the material, in interstate commerce or foreign commerce by means of the World Wide Web, making any communication for commercial purposes that is available to any minor and that includes any material that is harmful to minors.” (O’Brien, 2008 pg. 635) This new act limited the scope from the previous Communications Decency Act by one only applying it to materials displayed over the web. Second, it covers only communications made for commercial purposes and lastly COPA only restricts the category of “material harmful to minors,” a more narrow category than the CDA previously had. Congress listened to the feedback given the Court in issuing the Child Online Protection Act. The American Civil Liberties Union again steps in with the same contextual forces of protecting individuals First Amendment rights and claims this revision continues to violate those rights. Due to the prefigurative forces being illustrated by the process taking place we can observe Congress’s intentions remain to be to protect the youth from obscene materials on the Internet with only slight changes, while the reasons necessary for the District Court and circumstances are continually changing. By this it is meant that the circumstances surrounding how a case is brought up to the courts changes, yet for Congress the intention remains to protect minors; yet they cannot seem to do so in a manner consistent with what the Supreme Court deems within the limits of the Constitution. The District Court and appellate court did not agree with Congress, and again a conflict situation emerges between and act passed by Congress and the judicial branch. The appellate court affirmed the lower court decision and found that COPA was not narrowly tailored and was also not the least restrictive means of preventing minors from accessing harmful materials on the Internet. The Court put a preliminary injunction on the Act so that it could not be signed into law. If the passage of COPA counts as a violation of ones First Amendment Free Speech then there is an obligation to appeal to the Supreme Court in order to place a permanent injunction on the act. This is shown through the case Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union decided in June of 2004. The contextual forces that illuminate the intentions of the Supreme Court remain the 8 same, to uphold their power as a spokesperson for justice in terms of the Constitution. The Supreme Court decides based on their hierarchy to place a permanent injunction upon the Child Online Protection Act, declaring it to be unconstitutional under First Amendment protection claims. The “back and forth” process continues to illuminate the conflict relationship between these two branches of government and how over time we can see the social construction that is taking place to find a law that satisfies the intentions of both Congress and the Supreme Court. As previously shown, Congress interprets the Supreme Court decision in Ashcroft v. ACLU as feedback in order to revise and form another law that satisfies the boundaries. Since Congress views this part of the “conversation” as feedback, they are obligated to then make a more narrow law to protect the youth. This revision comes to be known as the Children’s Internet Protection Act passed in 2001. (President Clinton ends up signing this act into law). The contextual forces behind Congress now slightly changes with this law in that CIPA is not necessarily requiring the restriction of all materials deemed harmful to minors, but now requiring the use of filtering software in order to do so. This law proposes to limit minor’s exposure and access to pornography and various other explicit materials found online. In CIPA, Congress narrowly tailored the law so it specifically targeted the use of this filtering software as a safety control in public schools and libraries where access to unsupervised computers was more prominent. In addition, the law also mandated that if the use of the filtering software was not followed the federal government had the right to withhold federal funds from those institutions. This law is shortly challenged in the lower courts on a claim that CIPA still violates First Amendment rights to Free Speech and the right to view constitutionally protected materials on the Internet. The American Library Association (a change from the American Civil Liberties Union) is the group to challenge this law in the lower courts on these grounds. Although the organization challenging the law has changed, their contextual forces are relatively the same as the ACLU. The ALA is fighting for the rights of the public libraries to determine if they want to use the software, many are claiming that they should not be forced to limit what their customers can view when they are privately using the Internet. 9 An additional factor for the challenges against CIPA however is that there is the withholding of federal funds associate with non-compliance. The practical implications of this law are not only to protect individual rights, but also to not allow the government to have any further say in private actions. The District Court finds that Congress ahs successfully formed a law that remains within the confines of their powers, while at the same time enforcing their intentions of protecting the youth and innocence of the U.S. The American Library Association then feels it an obligation to appeal to the Supreme Court in order to reject the filtering requirements and withholding of federal funds. This comes to the Supreme Court as United States v. American Library Association. If the Court determines the appeal o be invalid, which they do, then they are obligated to uphold the Children’s Internet Protection Act because they found no First Amendment violations and that is was indeed constitutional. Finally, through the long and complicated “back and forth” process that has been shown the branches of government constructed constitutional law that was not found to infringe upon an individuals private right, as well as accomplish the goal of Congress to protect minors. The above information portrays how the serpentine model follows the conflict relationship and “conversation” process between Congress and the Supreme Court to construct a democratic process often seen throughout relations in the government. Discussion The Supreme Court, Congress, and the individual (whether it be the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Library Association, or the District Court in this example) create logic of interaction. It is through that logic of interaction, which can be considered as the conflict occurring between the branches, that democracy and democratic principles are being socially constructed. Without that conflict ensued at the very start of the process with the first attempt by Congress (the CDA) being shut down, the outcome could have been severely different. CMM and the serpentine model make this complicated process of construction of democracy easily viewed. There is not an extensive amount of research that explicitly examines the process that has been examined in the present case, making it even more helpful to use the serpentine model and the examples that have been used. Much of the process has been examined in the previous 10 section, describing the flow of the back and forth conversation between Congress and the Supreme Court. This is a continual process as long as the relationship between the parties exist there will be a pattern of interaction assisting in creating our social construction of democracy and reality as a whole. This is a prime example of that construction and pattern resulting from the inherent conflict that will always exist between Congress and the Supreme Court. Review of Literature The following reviews the relevant literature associated with the conflict relationship existing between the United States Congress and the Supreme Court. It is through this conflict and the use of the coordinated management of meaning theory that we can see the social construction of our democracy and the way in which conflict is such a significant part of the construction of our social realities. Please note not all of the referenced material will be included in the literature review for some were mostly used as a reference to check law standards and updates on the court cases and acts of Congress used in the examination. There have not been an extensive number of studies done on this particular relationship and its resulting effect, but the following pieces of literature illuminate the examinations that have been done and contribute greatly to the present study. A Proposal for Integrating Structuration Theory with Coordinated Management of Meaning Theory written by Randall A. Rose discusses the way in which the structuration theory can be integrated with the coordinated management of meaning theory (CMM). For the purpose of the study done in the research paper this piece of literature is being primarily used for its assistance in explaining and understanding the coordinated management of meaning theory. Having a thorough basic understanding of CMM is essential to understanding the study put forth, it is what the entire process and pattern is modeled around. CMM is what explains the pattern of which the Supreme 11 Court and Congress relationship and construction of Democracy rely upon. As this piece of literature states “…the coordinated management of meaning is the most comprehensive statement of social construction crafter by communication scholars.” (Rose, pg.174) Another essential factor Rose points to is the “recursive interplay” among the communication between those parties involved. These points, along with the frameworks of meaning are what enables’ individuals to understand the process presented in this study. There is a section beginning on page one hundred and seventy seven where the author specifically focuses upon an overview of CMM. This section includes use full information regarding the history, and emergence of this theory. The section also embodies the process, which the entire study on the social construction of Democracy relies. On a different note, the following pieces of literature will more so shift focus from the CMM and communications aspect of this study and give insight into the conflict relationship and history surrounding the Supreme Court and Congress over the years. Joseph Tanenhaus states many that go into the behavior of the Court in his article entitled, Supreme Court Attitudes Toward Federal Administrative Agencies. Tenenhaus determines these factors to be the external, the institutional, and the personal. As the article goes on to describe these three factors in detail it is realized that these help to form the hierarchy of the Supreme Court in the serpentine model used in the present study being researched. As seen throughout this study on the conflict relationship between Congress and the Supreme Court, the author confirms, that “…the Court has been confined to acting as overseer and to make certain that the agencies conduct themselves in accordance with…the Constitution.” (Tenenhaus, pg. 506) This gives support that the Court has this power of judgment and it is their duty to uphold this. The quantified data displayed in this article is interpreted to support the ideas of the relationship between Congress and the Supreme Court. This is a significant source of information for the study presented in this research. Similarly, Jonathan D. Casper undertakes to discuss the role of the Supreme Court in relation to policy making in the American legal system and the democratic process in his article The Supreme Court and National Policy Making. Specifically, this article looks 12 to the argument set forth by Robert A. Dahl. Dahl takes a traditional view of the Supreme Court in American society, seeing it as a “policy making institution.” (Casper, pg 50) The article states how Dahl chose to look at the approval for the majority members of Congress for certain legislation. In turn he then looks to the establishing framework to determine whether the Courts policy choices run contrary to the national majorities in Congress. Just as in some instance within the example used in the examination of the communication relationship between Congress and the Court, Dahl looks at those pieces of legislation that the court declares to be unconstitutional. This article is one of the closest linked studies found in relation to the examination this research paper has presented. Casper also eludes to the fact that if Congress believes something to be of a “major policy” issue they will not just allow it to end at the Court declaring it unconstitutional. Just as Congress did with the protection of the youth from harmful materials online legislation that twice got struck down as in violation of the Constitution, they continued to revise the acts and finally came the Children’s Internet Protection Act upheld by the Supreme Court. This study set forth originally by Dahl and elaborated on by Casper significantly supports the correlation of the conflict relationship between Congress and the Supreme Court. Congress and the Court, is a meeting report featuring Senator Charles Schumer and Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson, III reporting statements made during a meeting of the Assembly in Washington D.C. on March 21, 2002. This is an extremely interesting report, especially for the purposes of the examination being presented in this research paper. The meeting was established to discuss the extensive material in the Library of Congress documenting the history of the relationship between Congress and the Supreme Court. Senator Schumer began and first discussed his feelings toward the relationship between the branches. He goes into say that he has great respect for the judicial system. Generally speaking, Senator Schumer believes Congress makes the laws, the President implements them, and the Court was meant to interpret and apply the laws. He acknowledges the conflict that does exist between Congress and the Court and the power struggle for a balance. It is inherent in the roles that the two play for there to be some form of conflict. As for Judge J. Harvie, he says yes indeed there is a “frayed” relationship between the branches, yet it is through communication like this meeting that 13 there is an opportunity to restore a more balanced relationship. The ideas and beliefs of both the members of Congress and the members of the judicial system is illustrative of the relationship set forth in the examination of the “back and forth” process of CMM. This particular meeting transcript sheds a significant light upon this relationship and the inherent conflict that the process works with. Lastly, the article Explaining Congressional Attempts to Reverse Supreme Court Decisions written by Joseph Ignagni and James Meernik is significant to the pattern explained in the present research paper. In this article the authors examine the aspects that could lead Congress to attempt to revise those federal laws that have been declared unconstitutional in Supreme Court cases. Essentially, this is describing the conflict relationship between these branches, just as what has been illuminated in the research paper, yet without the process and communications aspect supporting it. This piece of literature significantly assist in understanding the struggle between the Supreme Court and the Congress and what goes into having to revise laws in order to pass Constitutional standards. Just as Congress had done in the specific examples used regarding Internet protection acts, they continually revised the laws proposed until they came to one that the Supreme Court finally accepted to be within the confines of the Constitution and did not violate any individuals First Amendment rights. The article alludes to the fact that there is not an extensive amount of research that had focused on the specific conflict between Congress and the Supreme Court, which has been previously mentioned in this section. Just as the authors intended with the model they set forth here, this study adds a great deal to future research on the conflict. The article gives a better understanding to both the congressional and judicial members and also an attempt at a more thorough explanation of the nature and depth of the conflict between them. This study was very interesting and hit the conflict between the branches perfectly, the only part missing for this article to be like the research begin presented in this paper is the communication process and the “back and forth’ to explain the construction made from the conflict. 14 References Casper, J. D. (1976). The supreme court and national policy making. American Political Science Review, 70(1), 50-63. Retrieved from JSTOR database. Clark, T. S. (2009). The separation of powers, court curbing, and judicial legitimacy. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 971-989. Retrieved from JSTOR database. Finkelman, Paul, and Melvin I. Urofsky. (2008). Landmark decisions of the united states supreme court (Second ed., pp. 613--615; 650; 662-663; 673-674). Washington D.C.: CQ Press. Hamilton, A. (1982). Federalist 78. The federalist papers (pp. 471-479). Westminster, MD: Bantam Dell Publishing Group. Handberg, R., & Hill, H. F., JR. (1980). Court curbing, court reversals, and judicial review: The supreme court versus congress. Law & Society Review, 14(2), 309-321. Retrieved from JSTOR database. Ignagni, Joseph and Meernik, James. (1994). Explaining congressional attempts to reverse supreme court decisions. Political Research Quarterly, 47(2), 353-371. Retrieved from Sage Publications, Inc. database. International Contributors, & Joseph B. Fazio. (2010). Chapter 19: Internet challenges to developing privacy law. Internet law and practice (2nd ed., pp. 19-1) Thomson Reuters/West. Johnson, J. W. (Ed.). (2001). Historic U.S. court cases. an encyclopedia (Second ed.). New York London: Routledge. O'Brien, D. M. (2008). Constitutional law and politics: Civil rights and liberties (7, Volume 2 ed.). New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc. Rose, R. R. (2006). A proposal for integrating structuration theory with coordinated management of meaning theory . Communication Studies, 57(2), 173-196. Retrieved from EBSCOhost database. Senator Charles Schumer and Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson, III. (2002). Congress and the court. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sceinces, 55(4), 37-69. Retrieved from JSTOR database. Street, Lawrence F., Grant, Mark P., Sandra Sheets Gardiner. (2010). Chapter 8: Censorship. Law of the internet (2nd ed., pp. 8-1) Matthew Bender & Company, Inc. 15 Tanenhaus, J. (1960). Supreme court attitudes toward federal administrative agencies. The Journal of Politics, 22(3), 502-524. Retrieved from Cambridge University Press database. Supreme Court Cases Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union 521 U.S. 844, 117 S.Ct. 2329 (1997) Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union 542 U.S. 656, 124 S.Ct. 2783 (2004) United States v. American Library Association 539 U.S. 126, 123 S.Ct. 2297 (2003) 16 Appendix A 17