AP--Realizing a Figured Bass

advertisement

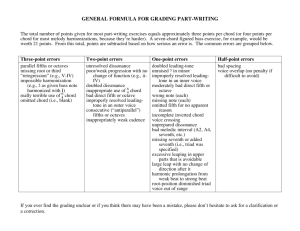

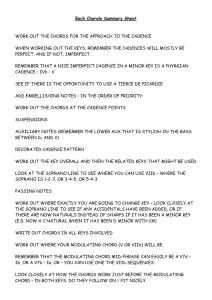

1 Realizing a Figured Bass Realizing figured basses has been a time-honored part of music theory courses for over 300 years. Students in contemporary AP Music Theory courses may wonder why figured bass is part of the curriculum, as it represents a compositional practice that was abandoned nearly 250 years ago! Despite this apparent anachronism, the activity of realizing figured basses carries many important skills, and actually can serve as a culminating activity in codifying several skills covered in an AP class throughout the academic year. Realizing figured bass tests students’ abilities to identify and spell triads and seventh chords, recognize their appropriate inversions based on figures, and to use the figures to compose in a four-part texture using principles of part-writing of the Common practice era. Lesson Summary This lesson presents a step-by-step approach to realizing a figured bass problem similar to those presented on the AP Music Theory exam. The lesson will present the process of realizing a figured bass, while also pointing out the requisite skills of chord spelling, spacing, doubling, and part-writing needed for students before they attempt this particular lesson. Connections to the AP Music Theory Curriculum Specifically, the skills, or essential questions, students need to know to be successful in this lesson are: Ability to identify triads and seventh chords and their inversions based on the figures provided above a given bass line. Ability to realize the figured bass by composing three additional voices in keyboard style or choral style above the bass, using good part-writing and counterpoint principles covered in class. Ability to label the chords with Roman numerals in the appropriate key. Ability to identify cadences, common chord progressions, and linear structures such as suspensions. As a result of this lesson, students should be able to find a systematic method for realizing a figured bass, while also codifying their knowledge of chord structure, chord progression, and part-writing. Finally, figured bass lessons can help students gain an appreciation for compositional and performance practice of early 18th century music. When singing or playing student figured bass examples at the keyboard, reasons for voice-leading, spacing and doubling become quickly apparent. 2 Teacher Prerequisite Knowledge In order to be effective in teaching figured bass, the teacher should be fluent in the being able to spell triads and seventh chords and identify these using figure bass symbols. Most importantly, the teacher should be familiar with the principles of good part-writing, including how to handle chord inversions (triads and sevenths) including especially 6/4 chords. Teachers should also be familiar with the various forms of suspensions and how these are normally prepared and resolved. It is important that teachers internalize these principles and be able to call them up readily, and not have to rely on textbooks as a reference for rules. It is a good idea to show students examples of figured bass writing in actual compositions, such as the Handel flute sonata shown below: This excerpt from Hermann Keller’s Thoroughbass Method (1965), shows a partially realized figured bass, and leaves the rest up to the student, should the teacher want to use the piece for further study. Student Prerequisite Knowledge Figured bass realization exercises are really the culmination of principles that students should be covering all year: chord spelling, chord inversion, part-writing in a four-part texture using Common Practice style counterpoint, identifying Arabic numeral figures as chord inversion symbols, and generating a Roman numeral analysis. Common Student Misconceptions One very common student misconception or confusion about figured bass is that they often don’t get the connection between the historical nature of the notation, i.e., the abbreviated nature of the figures themselves, and how such figures are linked with previous lessons about chord inversions. For example, when students see a “6” under a bass note, they may be confused that the only pitch called for is a sixth above the bass, when in fact, the solution is to write a triad in first inversion (which would call for a more extensive figure like: “8/6/3”). Some students may also confuse the concept of the figure above the bass with scale degrees: does “6” under a bass mean to write the 6th scale degree (submediant). Such misconceptions can be eliminated through reinforcing drills on work sheets, flash cards and other materials. 3 Another common problem is how to realize figures in minor keys that have only an accidental under the bass note. A lone accidental under a bass note indicates an altered third above the bass. It is important to emphasize that chord inversion labeling system that we teach is derived from the figured bass tradition. Related to this problem is a misconception that some figures indicate a chromatic alteration. For example a “#6” means that the pitch a sixth above the bass is supposed to be raised. However, does this mean that it is literally a sharp note above the bass, or just sixth raised a half-step in the key. As a teacher, it is important to teach within a system that corresponds to the practices of the AP exam. For the exam, the figures usually indicate the exact accidently (#3, b6, etc.) indicating that students should put the corresponding accidently next to the pitch. However, sometimes the AP exam will include the “/6” (sixth with a diagonal line through it), indicating merely that the sixth should be “raised,” so a diatonic flat would become a natural, a natural a sharp, and a sharp a double sharp, etc. Another common student misconception is the vertical figures vs. horizontal figures problem. Arabic numerals that are vertical indicate these intervals above a given bass note. A horizontal line means a linear motion above the bass. Most often the horizontal figures indicate a suspension figure of some kind, or a motion from a cadentil 6/4 chord (which is a sort of double suspension motion in itself). Teacher Outcomes This lesson should demonstrate the mutli-layered nature of a musical exercise of this kind and the importance of teaching a coherent sequence of topics throughtout the year, beginning with fundamentals of chord spelling, spacing, and doubling, and continuing on to Roman numeral analysis and counterpoint. The lessons also provides a template for students of a step-by-step approach to solving the problem that they should adopt when undertaking mastery of figured bass. Materials Needed Traditional Music notation materials are sufficient for this lesson, including: o Music staff paper and pencils, or o Music staff black- or whiteboard with markers Or, for more technologically equipped classrooms, o music notation software, such as Finale or Sibelius, can be used with o image projection on to a screen or a SmartBoard. Optional materials may include actual scores that have figured basses, such as scores by Corelli, Vivaldi, Handel, and J.S. Bach. Charles Burkhart’s Anthology for Musical Analysis contains good examples of pieces with figured bass, but other sources can be found with excellent examples as well. 4 Activity: Realizing a Figured Bass, Step by Step. Given the following problem: Have students follow a step-by-step guide to solve the problem. Step 1: Identify the key of the example. In this case, it appears to be in D major (and not b minor). Note: the Free-Response questions of the AP exam indicate the keys of the example, so this step is optional if teachers decide to indicate the key at the beginning. Step 2: Identify the chord roots. By doing this, the student has also identified the inversion of each chord. Formative Assessment: Back to the Future? If students are having difficulty with steps 1 and 2, then it is possible that they did not internalize several important lessons during the fundamentals unit at the beginning of the year. Now is the time to review/re-teach triad and diatonic seventh chord spelling and chord inversion lessons from the fundamentals portion of the course. Also, if students are having difficulty deciding what key the piece is in, the teacher can review key signatures in major and minor keys. Beyond that, the teacher can ask questions such as, 1) Is the example in major or minor keys? What are some of the indications for your decision? (Hopefully, the student will point to the beginning and ending pitches on D, and the V-Icadence implied by the A’s in the bass in m. 4, and the overall bass line that appears to present a functional chord progression in D major, and not B minor. The example is a good introduction to a figured bass problem. The teacher can note that the lack of a figure beneath the bass line indicates a chord in root position. The teacher can also note that the figures in the example correlated with the inversion symbols already covered. In fact, students should make the connection that these symbols derive from figured bass practice of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the use of these symbols is the main contribution of this practice to modern harmonic analysis. 5 Step 3: Write the Roman numerals for the chords. Writing RN’s at this stage will remind students of the chord roots. Formative Assessment: Why Roman numerals and why now? This part of the exercise will link students’ knowledge of chord structure with the Roman numeral analysis system. The figure 7/# in the sixth chord will provide a challenge for some students. Remind them that the lone accidental under the bass affects the third above the bass—in this case the third of the chord. The chromatic accidental also indicates that the chord is a chromatic chord—in this case a secondary dominant (V7/V). Many students who can realize this figure correctly might label the chord as a “II7” chord. Some theory texts also label the chord this way (and the label is acceptable on the AP exam), but students should really understand this chord as a secondary dominant, i.e., a chord that “tonicizes” the chord that follows. If students fail to correlate the figure with a Roman numeral, then students would probably benefit from a review of secondary dominants, their conception, spelling, and how they appear in figured bass. Step 4: Have students spell each chord. This will provide an inventory of the pitches to be used for each chord. Step 5: Given each chord, have students take a preliminary inventory of pitches that will (probably) be doubled. Formative Assessment: Lost in Space? Spacing and doubling rules are usually covered in the early stages of part writing. Students should be aware that root position triads generally have doubled roots. Seventh chords generally use all the voices, especially if the chord is inverted, but in root position, the fifth may be omitted in lieu of a doubled root. Other doublings are acceptable for root position triads depending on context. However, teachers should emphasize some strictures in doubling. For example, teachers should emphasize that students avoid doubling the leading tone (scale degree seven), chordal sevenths, chromatically altered pitches (such as the G-sharp in the V7/V chord, and special dissonances like the suspension in the last measure. 6/4 chords are unique and call for a different doubling strategy—the chordal fifth (the note in the bass) is the chord tone that is doubled in this case. 6 Step 6: Begin the part-writing process by composing a soprano line to go with the bass. Some students and teachers prefer to write out all four parts of each chord first, rather than composing a melodic line. This can be a perfectly acceptable approach, although emphasizing the composing of a soprano line first makes the student more aware of the linear qualities of these exercises and the importance of melody in general. Composing a melody line first also provides practice in writing good tonal counterpoint—a skill that applies to several other questions on the AP exam. There are several plausible melodies that could accompany this bass line, so when students compose a melody, one important consideration would be to consider the range and contour of the bass line. Here is one student’s solution to composing a melody line to the figured bass. After having student’s compose a melody, go on to the next step of the lesson. Step 7: Check for chord spelling and part-writing errors. It appears that this melody harmonizes with all the requisite chords of the figured bass. However, there are several problems with the melody, some of which are obvious in a casual glance, and some that will have inherent problems when other voices are added. The most obvious error in this example is the parallel fifths in bar 2 (in the V-vi progression). But there are also several more subtle errors. In measure 1, the ii6/5 chord will need a chordal seventh (the pitch D), and the most logical place to put that would be in the soprano, thus keeping a common tone between the first two chords. While a chordal seventh could be placed in another voice, it is much smoother to keep the D in the soprano. There are several other subtle errors remaining. In measure 4, the leap from E to G# in the soprano really calls attention to itself, and will create a false relation with the previous chord when other voices are added. The ii chord in that measure will need a G-natural to 7 harmonize, and that pitch should be the one to move to the chromatic G-sharp. Putting the G-sharp in the soprano precludes this possibility, so a different melody note would work better. The G-sharp is also the new “leading tone” for the tonicized V chord (the raised third of the V7/V chord), and because it is in the outer voice, must resolve upward to an A in the I 6/4 chord instead of down to the F-sharp. The final error is found in the last measure. Here, the student dutifully composes the 4-3 suspension in the soprano voice. While the suspension resolves correctly, the suspension is not prepared (by an anticipation, e.g., another G) in the same voice, as the E in the soprano of the penultimate chord precludes this possibility. Either the penultimate V7 soprano note should be changed to a G, or the suspension should be placed in an inner voice. Formative Assessment: Note to students: Don’t be afraid to use your eraser! (and Note to Teachers: Don’t be afraid to critique weak answers!) It is important that students (and teachers) check for errors continually throughout the exercise. Finding and correcting errors early in the problem-solving phase makes solutions easier as the lesson continues. More importantly, critiquing exercises, and especially having students critique exercises as a group, can lead to many interesting discussions on the principles of part-writing and counterpoint. This “student learning by doing” exercise can be more valuable than reading about these exercises in theory books. Indeed, theory students and budding composers have learned counterpoint in this way for hundreds of years! A list of “dos and don’ts” for part writing are provided in the Appendix of this chapter. These are the basic part-writing rules covered in the AP curriculum, some of which are considered more significant than others. Other rules can certainly be covered in your own AP class. Step 8: Re-compose the melody line Here, the student opted to recompose the melody, retaining the D in the first two chords and then making a descending line to the B. There is one leap in the melody: the ascending minor third from B to D in measure 3. 8 Step 9: Check (Again) for Part-Writing Errors By using oblique and contrary motion, the student erased the potential for parallel fifths and octaves, at least in the outer voices. Since there are seventh chords in the example, the student should watch out for the sevenths and make certain that they are approached and resolved correctly. In this example, the ii6/5 chord in measure 1 now has the seventh in the soprano, and it is approached by common tone and resolves down, all of which is acceptable. The V7/V chord also features the seventh in the soprano. It is approached by the small leap (which is acceptable, although not optimal), and resolves by common tone. Actually, the seventh eventually resolves down, but the resolution is delayed by the cadential I 6/4 chord. So, this soprano can be said to have no errors. While the melody appears that might work, the distance between soprano and bass becomes rather tight by measure 2. This could present difficulties when composing the inner voices. Thus, spacing could become a factor in a successful solution to the problem. Step 10: Compose the inner voices. Step 11: Check (again and again) for Errors. Upon composing the inner parts, our suspicions about spacing are confirmed. Although the student sought to write the inner parts with smooth voice leading, there are many errors in the inner voices. The second chord (ii6/5) has a tripled third, and no root or fifth (inverted seventh chords should have all chord members present). There are parallel unisons and octaves between chords two and three in the bass, tenor and alto. Chord four (vi) has no third. Once again, the G-sharp in the V7/V chord is not prepared correctly and creates a false relation with the G-natural in the tenor in the previous chord. The cadential I 6/4 in measure four has a doubled bass, but no third. The V7 chord has voice crossing in the tenor and bass. Finally, the suspension in the alto is not prepared (the preparation note G is in the tenor crossing the bass), and though the seventh in the tenor resolves correctly by moving down it creates an incorrect doubling, and an unnecessary dissonance with the F-sharp in the tenor. Formative Assessment: More rules to consider…. Errors such as those found in Step 11 point out the need to cover some subtle rules of counterpoint, and also the importance of students’ understanding of how suspensions 9 work. Errors such as these point out the need to discuss the false relation, voice crossing, as well as review more egregious errors such as parallel fifths, octaves, and in this case, unisons! Also, the topic of suspensions requires an extensive unit within an AP curriculum. Suspensions are linear entities that exist to create a sense of tension by delaying the resolution of certain chord tones. In this example, the I6/4 chord (though not explicitly called a “suspension,” delays the resolution of the chordal seventh of the V7/V chord. The ensuing 4-3 suspension in the last measure delays the resolution of the chordal seventh of the V7 chord. 4-3 suspensions are common, but so are 6-5, 7-6, 9-8, and 2-3 (that feature the suspended note in the bass). Consult your theory text for full coverage of suspensions. Finally, a big problem with the solution above is a spacing issues: the student did not allow enough room between outer voices to accommodate the inner parts. This example has a bass line that extends into the upper part of the bass clef staff, so the teacher will want to emphasize that students compose the soprano line higher in order to use contrary motion with the bass, and at the same time, allow more room for the inner voices to operate. Adequate spacing becomes a factor in this example. Step 12: Re-Re-Compose the soprano line, and adjust the inner voices. Here, the student re-composed the soprano voice higher to accommodate the inner voices, given the ascending motion of the bass line. This re-composing provided an overall contrary motion between bass and soprano, while adding some flexibility in the recomposed inner voices. Finally, all the adjustments have resulted in a satisfactory response to the question. Formative Assessment: Do it Until You Get it Right! A satisfactory response such as the one in Step 12 can be useful in teaching, for not only do we look for errors to correct, but we can also note the good features of the example as well. In this example, the teacher should note the following positive attributes: The ii6/5 chord has all chord members, and the chordal seventh resolves correctly (downward). The V-vi progression features contrary motion between the bass and the three upper voices, so parallel fifths and octaves are avoided. 10 The chromatically altered pitch in the V7/V chord, the G-sharp, is prepared by the G-natural in the same voice in the previous chord, thus eliminating the possibility of the false relation. The resolution of the chordal seventh in the V7/V chord is delayed by the cadential I6/4 chord. The chordal seventh (D) is suspended by the I6/4 chord, and resolved in the penultimate chord to the C-sharp. The G-sharp as the new “leading tone” of the V7/V chord normally should resolve up, but since it is in an inner voice (the alto), the downward motion to the F-sharp is acceptable, and indeed, preferable in this case, as there would be no third to the chord otherwise. As stepwise motion, the G-sharp to F-sharp is not considered an awkward or dissonant leap. The cadential I6/4 chord has the doubled bass, and the chord resolves normally to the V7 chord, setting up the perfect authentic cadence. Finally, the 4-3 suspension is at last prepared by the common tone, and resolves normally down by step. Step 13 (optional): Discuss alternative solutions The solution found in Step 12 is not the only solution to the problem. It is often fun and interesting to show other plausible solutions to the problem, and to have students identify the pros and cons of each solution. For example, one solution may look like this: This solution is plausible, but has one error—the incorrect resolution of the chordal seventh in the V7/V chord. There is also a jump in the tenor in the third chord, and while not incorrect, leads to some disjunct voice leading. Reflections on Formative Assessment The complexity of realizing a figured bass exercise should now be apparent after reading through this exercise. The exercise offers the opportunity for students to demonstrate their knowledge of chord spelling, inversions, Roman numeral analysis, part-writing, and the employment of certain non-harmonic tones like suspensions. These skills provide an effective curricular scaffolding throughout the AP course, and the exercises offer a good opportunity to test the knowledge of the student in these areas. 11 Summative Assessment An exam that consists exercises like the one above is helpful for students to master the problem of realizing figured bass, and to help improve their skills. Exams also force students to work faster, requiring them to truly internalize chord spelling skills and partwriting concepts to the point where they become nearly automatic. Test materials are easily accessible. Nearly all music theory textbooks have figured bass examples in them, and old free-response questions from the AP Central may be adapted as suitable testing material. There are many ways to evaluate a figured bass exam. Problems can be graded holistically, with verbal comments provided as feedback for performance, and a letter grade can be derived from the nature of the comments. Exams can also be quantified for a finer calibration of the student’s work. Points can be given for chord spelling, doubling, part-writing, and so forth. Teachers may want to refer to the AP scoring guides for free response questions 5 and 6 in order to get an idea of how AP readers evaluated these questions. For FR 5, graders check Roman numerals first, and each correct RN receives one point. Next, graders check chord spelling, spacing and doubling. Incorrect chord spellings receive zero points, and aberrant spacings and doublings generally receive ½ point. Finally, graders check voice leading, giving two points for each connection between chords. Note that incorrectly spelled chords receive no points for voice leading, as it is not possible to evaluate voice leading for chords that are spelled incorrectly. So, it is imperative that students at least be able to spell chords correctly! Resources Textbooks Most college-level theory textbooks have brief explanations of figured bass, and a few offer cursory examples from the literature. A couple of current texts are notable in that they offer more than just a cursory coverage of the subject. Two of these are: Laitz, Steven (2011). The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Tonal Theory, Analysis, and Listening. New York: Oxford University Press. In addition to a brief introduction, this book has coverage of realizing figure bass in an appendix. Also, Laitz covers figured bass in suspensions later in volume 1. Roig-Francolli, Miguel (2003. Harmony in Context. Boston: McGraw-Hill. 12 In addition to coverage of the fundamentals to figured bass, Roig-Francoli provides a “A Figured Bass Checklist” (p. 107), and a “Procedure for Realizing a Figured Bass” (p. 220-222). Coverage in figured bass is more extensive in “integrated” music theory and literature texts of the 1980s and 1990s, many of which are out of print, but may be available. Some of these texts are as follows: Baur, John (1985) Music Theory Through Literature. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall. Extensive coverage of figured bass with examples by Corelli, Purcell, and Johann Sebastian Bach. Kraft, Leo (1987). Gradus: An Integrated Approach to Harmony, Counterpoint, and Analysis, vols. 1 and 2. Second Edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Co. More pieces from the literature involving figured bass. Primary Sources These are interesting sources to show students how figured bass was conceived and how it was taught in the past. Gasparini, Francesco ( 1708/1963). The Practical Harmonist at the Harpsichord. Translated by Frank S. Stillings. Edited by David L. Burrows. New Haven: Yale University Press. Lessons on harmony and counterpoint from a 17th century Italian master! Godbe, Samuel. (1794/1976). Mozart's Practical Elements of Thorough-Bass. New York: J. Patelson Music House, 1976. A recounting of Mozart’s harmony and figured lessons from one of his English pupils. Keller, Hermann (1965). Thoroughbass Method; with Excerpts from the Theoretical Works of Praetorius [and others] and Numerous Examples from the Literature of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Translated and Edited by Carl Parrish. New York: W.W. Norton Co. Lebetter, David (1990). Continuo Playing According to Handel: His Figured Bass Exercises (Oxford Early Music Series). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 13 Web sites for Figure Bass Harmony Exercises SFCM Theory.com Online Materials. Figure Harmony Exercises. http://www.sfcmtheory.com/figured_harmony/figured_harmony.htm Part of San Francisco Conservatory of Music online resources, this site provides some two-part examples for realization. The examples look like 18th century keyboard pieces that could exist as “real” music. Exercises can be downloaded as pdf files. MyMusicTheory.com. Grade Six Music Theory—Harmony Lesson 8: Figured Bass http://www.mymusictheory.com/grade6/lessons/a8-figured-bass.html MyMusicTheory.com. A good, brief walk through of figured bass and solution of a sample problem (similar to this article!) Ars-Nova.com. Realizing Harmony from Figured Bass. http://www.ars-nova.com/CounterpointStudy/figuredbass.html Another brief introduction to figured bass . PARKarts. Worksheet #1: Inversions with Figured Bass and V7 chords. https://parkarts.pbworks.com/w/page/14426432/Worksheet%20%231%3A%20Inversions %20with%20Figured%20Bass%20and%20V7%20Chords Downloadable worksheets of figured bass examples. Dolmetsch online. Music Theory online: Figured Bass. http://www.dolmetsch.com/musictheory18.htm A brief overview of figured bass, illustrated with music by Praetorius and Geminiani. davesmey.com/brooklynconservatory/ A brief, yet informative explanation of the fundamentals of figured bass notation, dealing specifically with chord inversion. 14 Appendix: Common Part Writing Errors, as Stated in AP Exam Scoring Guides. “Egregious” Errors: 1. Parallel octaves, fifths, or unisons occur (immediately successive or on successive beats), including those by contrary motion. 2. Uncharacteristic melodic leaps occur (e.g., augmented second, tritone, or more than a fifth). 3. Chordal sevenths are unresolved or resolved incorrectly. (The voice with the seventh must move down by step if possible. In some cases, such as ii7 to cadential 64, the seventh may be retained in the same voice or transferred to another voice.) 4. The leading tone in an outer voice is unresolved or resolved incorrectly. 5. The 6th or 4th of a 64 chord is unresolved or resolved incorrectly. 6. At least one of the chords has more or fewer than four voices (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass). Less “Egregious” Errors: 1. Uncharacteristic rising unequal fifths. 2. Uncharacteristic hidden (covered) or direct octaves or fifths between outer voices. 3. Overlapping voices. Definition: Two voices move to a position in which the lower voice is higher than the previous note in the higher voice, or they move to a position where the higher voice is lower than the previous note in the lower voice. 4. Motion leading to a chord with crossed voices. Definition: Voicing in which the normal relative position of voices is violated, e.g., if the soprano is below the alto or the bass is above the tenor. 5. A chordal seventh approached by a descending leap.