CDChap11Slides

advertisement

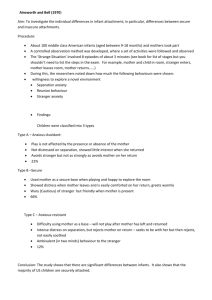

Attachment to Others and Development of Self How Children Develop (3rd ed.) Siegler, DeLoache & Eisenberg Chapter 11 Attachment An emotional bond with a specific person that is enduring across space and time The observations of John Bowlby and others involved with institutionalized children led to an understanding of the importance of parentchild interactions in development. Attachment Many investigators now believe that children’s early relationships with parents influence the nature of their interactions with others from infancy into adulthood, as well as their feelings about their own worth. Overview I. The Caregiver-Child Attachment Relationship II. Conceptions of the Self III. Ethnic Identity IV. Sexual Identity or Orientation V. Self-Esteem I. The Caregiver-Child Attachment Relationship A. Attachment Theory B. Measurement of Attachment Security C. Cultural Variations in Attachment D. Factors Associated with the Security of Children’s Attachment E. Does Security of Attachment Have Long-Term Effects? I. Caregiver-Child Attachment Relationship Harry Harlow’s experimental work with monkeys who were deprived of all early social interactions strongly supported the view that healthy social and emotional development is rooted in children’s early social interactions with adults. A. Attachment Theory John Bowlby proposed attachment theory, which is influenced by ethological theory and posits that children are biologically predisposed to develop attachments with caregivers as a means of increasing the chances of their own survival. 1. Bowlby’s Attachment Theory Secure base is Bowlby’s term for an attachment figure’s presence that provides an infant or toddler with a sense of security that makes it possible for the infant to explore the environment. Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby’s student, extended and tested his ideas. Bowlby’s Four Phases of Attachment 1. Preattachment phase (birth to 6 weeks) The infant produces innate signals that bring others to his or her side and is comforted by the interaction that follows. 2. Attachment-in-the-making (6 weeks to 6-8 months) The phase in which infants begin to respond preferentially to familiar people. Bowlby’s Four Phases of Attachment 3. Clear-cut attachment (between 6-8 months and 1½-2 years) Characterized by the infant’s actively seeking contact with their regular caregivers and typically showing separation protest or distress when the caregiver departs 4. Reciprocal relationships (from 1½ or 2 years on) Involves children taking an active role in developing working partnerships with their caregivers Internal Working Model of Attachment The child develops a mental representation of the self, of attachment figures, and of relationships in general. This working model guides children’s interactions with caregivers and other people in infancy and at older ages. 2. Ainsworth’s Research Ainsworth developed a laboratory procedure called “The Strange Situation” to assess infants’ attachment to their primary caregivers. In this procedure, the child is exposed to seven episodes, including two separations and reunions with the caregiver and interactions with a stranger when alone and when the caregiver is in the room. Using this procedure, Ainsworth identified three attachment categories. Episodes in Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure B. Measurement of Attachment Security in Infancy 1. Secure attachment is a pattern of attachment in which an infant or child has a high-quality, relatively unambivalent relationship with his or her attachment figure. In the Strange Situation, a securely attached infant, for example, may be upset when the caregiver leaves but may be happy to see the caregiver return, recovering quickly from any distress. When children are securely attached, they can use caregivers as a secure base for exploration. About two-thirds of American middle class children are securely attached. Attachment Classifications 2. Insecure/resistant (or ambivalent) attachment is a pattern in which infants or young children (about 15% of American middle class children) are clingy and stay close to their caregiver rather than explore the environment. • In the Strange Situation, insecure/resistant infants tend to become very upset when the caregiver leaves them alone in the room, and are not readily comforted by strangers. • When the caregiver returns, they are not easily comforted and both seek comfort and resist efforts by the caregiver to comfort them. Attachment Classifications 3. Insecure/avoidant attachment is a type of insecure attachment in which infants or young children (about 20% of infants from middleclass U.S. families) seem somewhat indifferent toward their caregiver and may even avoid the caregiver. In the Strange Situation, these children seem indifferent toward their caregiver before the caregiver leaves the room and indifferent or avoidant when the caregiver returns. If these children become upset when left alone, they are as easily comforted by a stranger as by the caregiver. Attachment Classifications 4. Because a small percentage of children did not fit into these categories, a fourth category, disorganized/disoriented attachment, was subsequently identified. Infants in this category seem to have no consistent way of coping with the stress of the Strange Situation. Their behavior is often confused or even contradictory, and they often appear dazed or disoriented. C. Cultural Variations in Attachment To a great extent, infants’ behaviors in the Strange Situation are similar across numerous cultures, including in China, Western Europe, and various parts of Africa. There are, however, some important differences in behavior in the Strange Situation in certain other cultures. Attachment Across Cultures Types of insecure attachment in the United States and Japan differ, with all insecurely attached Japanese infants classified as insecure/resistant. This may reflect the emphasis on dependence and closeness between Japanese infants and their mothers and Japanese infants’ anger and resentment at being denied contact in the Strange Situation. Parents with secure adult attachments tend to have securely attached children. D. Factors Associated with the Security of Children’s Attachment Parental sensitivity contributes to the security of an infant’s attachment. Can be exhibited in a variety of ways: Responsive caregiving when children are distressed or upset Helping children to engage in learning situations by providing just enough, but not too much, guidance and supervision Intervention studies, in which parents in an experimental group are trained to be more sensitive in their caregiving, indicate a causal relationship between parental sensitivity and security of attachment. Interventions and Attachment In a study conducted in the Netherlands, half of a group of mothers of 6-month-old babies at some risk for insecure attachment were randomly assigned to a condition in which sensitivity was trained, with the remaining half in a comparison condition. Three months later, more of the infants of the mothers in the experimental group were securely attached than were those in the control group. The differences in attachment were still apparent when the children were 18 months, 24 months, and 3½ years old. E. Does Security of Attachment Have Long-Term Effects? Children who were securely attached as infants seem to have closer, more harmonious relationships with peers than do insecurely attached children. Secure attachment in infancy also predicts positive peer and romantic relationships and emotional health in adolescence. Securely attached children also earn higher grades and are more involved in school than insecurely attached children. Long-Term Effects It is unclear, however, whether security of attachment in infancy has a direct effect on later development, or whether early security of attachment predicts children’s functioning because “good” parents remain “good” parents. It is likely that children’s development can be better predicted from the combination of both their early attachment status and the quality of subsequent parenting than from either factor alone. II. Conceptions of the Self A. The Development of Conceptions of Self B. Identity in Adolescence The Self Refers to a conceptual system made up of one’s thoughts and attitudes about oneself An individual’s conceptions about the self can include thoughts about one’s own physical being, social roles and relationships, and “spiritual” or internal characteristics. A. Development of Conceptions of Self Children’s sense of self emerges in the early years of life and continues to develop into adulthood, becoming more complex as the individual’s emotional and cognitive development deepens. Adults contribute to the child’s selfimage by providing descriptive information about the child. 1. The Self in Infancy Infants have a rudimentary sense of self in the first months of life, as evidenced by their control of objects outside of themselves. Their sense of self becomes more distinct at about 8 months of age, when they respond to separation from primary caregivers with separation distress. 1. The Self in Infancy By 18 to 20 months of age, many children can look into a mirror and realize that the image they see there is themselves. By 30 months of age, almost all children recognize their own photograph. Two-year-old children’s exhibition of embarrassment and shame, their self-assertive behavior, and their use of language also indicate their self-awareness. 2. The Self in Childhood At age 3 to 4, children understand themselves in terms of concrete, observable characteristics related to physical attributes, physical activities and abilities, and psychological traits. Their self-evaluations during the preschool years are unrealistically positive. Children begin to refine their conceptions of self in elementary school, in part because they increasingly engage in social comparison, the process of comparing aspects of one’s own psychological, behavioral, or physical functioning to that of others in order to evaluate oneself. The Developing Sense of Self By middle to late elementary school, children’s conceptions of self begin to become integrated and more broadly encompassing, reflecting cognitive advances in the ability to use higher-order concepts. In addition, older children can coordinate opposing self-representations and are inclined to compare themselves with others on the basis of objective performance. 3. The Self in Adolescence III. Ethnic Identity A. Ethnic Identity in Childhood B. Ethnic Identity in Adolescence Ethnic Identity Refers to individual’s sense of belonging to an ethnic group, including the degree to which they associate their thinking, perceptions, feelings, and behavior with membership in that ethnic group A. Ethnic Identity in Childhood Children’s ethnic identity has five components: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Ethnic knowledge: Knowledge that their ethnic group has certain distinguishing characteristics Ethnic self-identification: The categorization of themselves as members of their ethnic group Ethnic constancy: The understanding that the distinguishing characteristics of their ethnic group that they carry in themselves do not change across time and place Ethnic-role behaviors: Engagement in the behaviors that reflect the distinguishing characteristics of their ethnic group Ethnic feelings and preferences: Feelings about belonging to an ethnic group and their preferences for its members and the characteristics that define it Examples of Components of Ethnic Identity Development of Ethnic Identity Ethnic identity develops gradually during childhood and is not universal. By the early school years, ethnicminority children know the common characteristics of their ethnic group, start to have feelings about being members of the group, and may have begun to form ethnically-based preferences. Development of Ethnic Identity Children tend to identify themselves with their ethnic group between the ages of 5 and 8. Shortly after that, they begin to understand their ethnicity as unchanging. The family and the larger social environment play a major role in the development of ethnic identity. B. Ethnic Identity in Adolescence IV. Sexual Identity or Orientation A. The Origins of Youths’ Sexual Identity B. Sexual Identity in Sexual-Minority Youth Sexual Orientation A person’s preference in regard to males or females as objects of erotic feelings A core component of adolescent identity Dealing with new feelings of sexuality is difficult for many adolescents, but establishing a sexual identity is much harder for some adolescents than for others. A. The Origins of Youth’s Sexual Identity Puberty is the most likely time for youth to begin experiencing feelings of sexual attraction to others. Most current theorists believe that feelings of sexual attraction to others are based primarily on biological factors, although the environment may also be a contributing factor. B. Sexual Identity in Sexual Minority Youth Sexual-minority youth are young people who experience same-sex attractions and for whom the question of personal sexual identity is often confusing and painful. It is difficult to know exactly how many youth fit in this category, but current estimates indicate that 24% of high students in the U.S. identify themselves as gay, lesbian or bisexual. However, many sexualminority youth don’t self-identify until early adulthood or later. Increasing numbers of sexual-minority youth are disclosing this information to others (i.e., “coming out”) and are doing so at earlier ages than in previous cohorts. 2. Consequences of Coming Out Typically, sexual-minority youth do not disclose their same-sex preferences to peers or siblings until about 16½ to 19 years of age and do not tell their parents until a year or two later, if at all. Surveys show that about 20-40% of sexual-minority youth are insulted or threatened by relatives after they reveal their sexual identity. Heterosexual adolescents tend to be not very accepting of same-sex preferences in peers. Presumably because of the pressures of coping with their sexuality, sexual-minority youth have higher reported rates of attempted suicide than other youth. V. Self-Esteem A. Sources of Self-Esteem B. Self-Esteem in Minority Children C. Culture and Self-Esteem Self-Esteem One’s overall evaluation of the worth of the self and the feelings that this evaluation engenders Related to how satisfied people are with their lives and their overall outlook Starts to develop early and is affected by a variety of factors throughout life A. Sources of Self-Esteem Involves the interaction of nature and nurture, including the sociocultural context. There are large individual differences in selfesteem. 1. Heredity Heredity contributes to self-esteem in terms of physical appearance, athletic ability, and aspects of intelligence and personality (e.g., self-esteem is more similar in siblings who are closer genetically). The genetic contribution to self-esteem appears to be stronger for boys than for girls. 2. Others’ Contributions to Self-Esteem Children begin to become concerned about winning their parents’ love and approval at about age 2. Parents who tend to be accepting and involved with their child and who use supportive yet firm childrearing practices tend to have children with higher self-esteem. Parents who reject their children for unacceptable behavior (rather than condemning the specific behavior) are likely to instill their children with a sense of worthlessness. Factors Contributing to Children’s Self-Esteem 2. Others’ Contributions to Self-Esteem Over the course of childhood, selfesteem is increasingly affected by peer acceptance and is also likely to affect how peers respond to individual children. Self-esteem is increasingly affected by internalized standards as children approach adolescence. 3. School and Neighborhood A decline in self-esteem is associated with the transition from elementary to junior high school. Living in poverty in an urban environment is associated with lower self-esteem among adolescents in the United States. B. Self-Esteem in Minority Children Although young Euro-American children tend to have higher selfesteem than their African-American peers, the trend reverses slightly after age 10. Less is known about the self-esteem of Latino and other minority children. Minority-group parents can help their children develop high self-esteem and a sense of wellbeing by instilling them with pride in their culture, by being supportive, and by helping them to deal with prejudice. C. Culture and Self-Esteem Self-esteem scores tend to be lower in China, Japan, and Korea than in many Western nations. There appear to be fundamental differences between Asian and Western cultures that affect the very meaning of self-esteem.