Spring Forces and Simple Harmonic Motion

advertisement

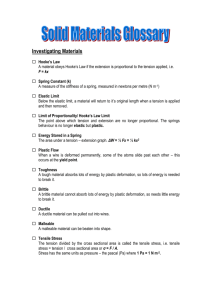

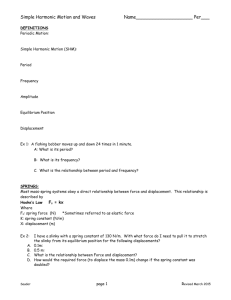

Spring Forces and Simple Harmonic Motion Chapter 10 Expectations At the end of this chapter, students will be able to: Apply Hooke’s Law to the calculation of spring forces. Conceptually understand how simple harmonic motion is caused by forces and torques obeying Hooke’s Law. Calculate displacements, velocities, accelerations, and frequencies for objects undergoing simple harmonic motion. Expectations At the end of this chapter, students will be able to: Calculate the elastic potential energy resulting from work done by spring forces. Understand how pendulums approximate simple harmonic motion. Calculate the natural frequencies of both simple and physical pendulums. Conceptually understand the ideas of damped, driven, and resonant simple harmonic motion. Expectations At the end of this chapter, students will be able to: Analyze the elastic deformation of objects in terms of stress, strain, and the elastic moduli of materials. Express Hooke’s Law in terms of stress and strain. Spring Forces A spring resists being stretched or compressed. Spring Forces The force with which the spring resists is proportional to the distance through which it is compressed or stretched: F kx “spring constant” SI units: N/m Spring Forces – Hooke’s Law F kx This relationship is called Hooke’s Law. Hooke’s Law Robert Hooke 1635 – 1703 English mathematician and natural philosopher; contemporary of Isaac Newton Early builder of microscopes and telescopes Hooke’s Law The direction of the spring force is always opposite the direction of the stretching or compression of the spring – hence, the minus sign. F kx A Consequence of Hooke’s Law Consider Newton’s second law and Hooke’s Law simultaneously: F ma kx k a x m Now, a small and sneaky bit of calculus: d 2x k a 2 x dt m differential equation x A cos t its solution Simple Harmonic Motion Motion described by this equation: x Acost displacement (m) angular frequency (rad/s) time (s) amplitude (m) is called simple harmonic motion (SHM). It is: periodic (repeats itself in time) oscillatory (takes place over a limited spatial range) Simple Harmonic Motion x Acost displacement vs. t A = 1.00 m 1.00 0.80 0.60 displacement, m 0.40 0.20 0.00 -0.20 -0.40 -0.60 -0.80 -1.00 0.00 2.00 4.00 6.00 8.00 t, rad 10.00 12.00 14.00 SHM: Reference Circle Representation Y A vector of magnitude A rotates about the origin with an angular velocity . A cos t A t X The x component of the vector represents the displacement. SHM: Frequency Since there are 2p radians in each trip (“cycle”) around the reference circle, the “cycle” frequency is related to the angular frequency by 2pf or f 2p SI units of “cycle” frequency, f: cycles / s = Hertz (Hz) SHM: Velocity Y We can calculate the velocity from the reference circle representation: vT r A vT sin t A sin t v A sin t - vT sin t vT t A t X SHM: Acceleration Y aC r A 2 2 a aC cos t -aC cos t t aC t X a A cos t 2 SHM: Velocity and Acceleration must be expressed in rad/s. Like displacement, velocity and acceleration are periodic in time. Maximum velocity: vmax A 2 a A Maximum acceleration: max Acceleration has maximum magnitude at extremes of displacement. Velocity has maximum magnitude when displacement is zero. Mass on a Spring System Natural frequency for a mass m on a spring with spring constant k: d 2x k a 2 x dt m k 2pf m x A cos t Work Done in Straining a Spring Stretch or compress a spring by a displacement x from its unstrained length. Initial force: F0 = 0 Average force: Final force: Fmax = kx 1 F kx 2 1 2 Work over a displacement x: W F x W kx 2 Elastic Potential Energy The spring force is a conservative force: Like all conservative forces, its work is pathindependent. Like all conservative forces, it is associated with a form of stored or potential energy. Elastic potential energy: 1 2 EPE kx 2 Total Mechanical Energy We add another term: E KE KER GPE EPE 1 2 1 2 1 2 E mv I mgh kx 2 2 2 The Simple Pendulum A simple pendulum is a particle attached to one end of a massless cord of length L. It is able to swing freely and without friction from the other end of the cord. Its frequency: 2pf g L L The Physical Pendulum A physical pendulum is any real object (mass m) suspended a distance L from its center of gravity, able to swing freely and without friction from the suspension point. mgL Its frequency: 2pf I L Physical-Simple Correspondence Notice that a simple pendulum would have a moment of inertia: I mL2 Substitute: mgL mgL 2 I mL g L As a physical pendulum becomes a simple one, its frequency “collapses” to that of a simple pendulum. Small-Angle Approximation L R TL sin cos T sin Result: the restoring torque increases with angle, but at less than a linear rate. T cos The restoring torque on a pendulum does not actually have the Hooke’s Law form: mg Small-Angle Approximation How much less? , ° % under linear 0.10 0.0002% 1.0 0.02% 2.0 0.08% 5.0 0.51% 10 2.0% Damped Oscillations If the only force doing work on an object is the spring force (conservative), its mechanical energy is conserved. If frictional forces also do work, the object’s mechanical energy decreases, and the SHM is called damped. If the frictional force is just large enough to prevent oscillation as the object reaches its equilibrium position, it is called critically damped. Driven Oscillations If a driving force acts on an object in addition to a Hooke’s Law restoring force, the harmonic motion of the object is called driven. Example: a tree in a gusty wind. Driven Oscillations: Resonance If the driving force is periodic, and is applied at the natural frequency of the oscillating object, the work done on the object adds up over multiple cycles of motion, and large-amplitude motion results. This is called resonance. The natural frequency is sometimes called the resonant frequency. Example: a person on a swing, being pushed by another person. Material Deformation: Everything is a Spring Solid materials are interconnected, microscopically, by powerful intermolecular bonding forces. These forces behave like springs … with really large spring constants. Because of them, material objects resist deformations, such as compression, elongation, or shearing. Tension and Compression A force acts to increase the length of an object: fractional change in length applied force L F Y A L0 cross- Young’s modulus sectional SI units = N/m2 area Thomas Young 1773 - 1829 English physicist, physician, and Egyptologist Famous mostly for his work in optics Shear A pair of forces act to shear an object (deform it slantwise): applied force X FS A L0 Shear modulus SI units = N/m2 cross-sectional area Shear 1945 - ? Has only one name English physicist and pop musician Inventor of the shear modulus Rumored to have appeared in the 1983 version of Dune Volume Deformation In order to discuss volume deformation, it is necessary to define a new force-related quantity: pressure. Pressure is the ratio of the magnitude of a force applied perpendicular to a surface to the area of that surface: F P A SI units: N/m2 = Pascals (Pa) Blaise Pascal 1623 – 1662 French mathematician Invented the first digital calculator (the “Pascaline”) Volume Deformation A change in pressure changes the volume of an object: pressure change V P B V0 fractional bulk modulus change in SI units: N/m2 volume Stress and Strain Stress is the deforming force applied to an object, divided by its cross-sectional area: F stress A Stress has SI units of N/m2 (just as pressure and the elastic moduli have). Stress and Strain Strain is the change in a dimensional quantity expressed as a fraction of its un-deformed value: L X V strain or strain or strain L0 L0 V0 Strain is a dimensionless, unitless ratio. Strain is the result of stress on a material object. Stress and Strain Consider the defining equation for Young’s modulus: L F Y A L0 Rearrange: F L Y A L0 To restate: stress elastic modulus strain This is the stress-strain formulation of Hooke’s Law. Summary: Elastic Moduli deformation elastic modulus length Young’s modulus (Y) shear shear modulus (S) volume bulk modulus (B) all moduli have the same SI units: N/m2 = Pa equation L F Y A L0 X FS A L0 V P B V0