Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go Teaching First

advertisement

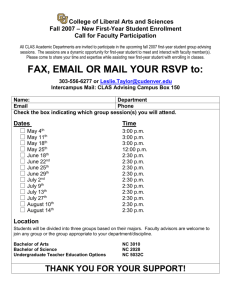

Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go First: Connecting Information Needs to e-resources Elizabeth C. Whipple, Margaret (Peggy) W. Richwine, Kellie N. Kaneshiro, and Frances A. Brahmi Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN ABSTRACT The purpose of this project was to introduce first-year medical students to electronic resources that are best suited for different types of background questions. Specific questions from a case study were presented, and the students generalized them into a ‘‘type’’ of question. They then identified the best eresources for that type of question. This is their first introduction to the lifelong learning competency in the Indiana University School of Medicine competency-based curriculum. KEYWORDS Electronic resources, medical education, medical students, problem-based learning Full reference can be found at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02763860902816909#.Um_SrVMntaU 1 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go INTRODUCTION Different information resources are useful at different stages throughout the formal education of medical students. During the fall semester of medical school, the Ruth Lilly Medical Library introduced first-year medical students at the Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) to the electronic resources (e-resources) available to students. The method of dissemination employed a problem-based learning style. Information was presented in a didactic setting, followed by hands on exploration, discussion, and evaluation of the resources. BACKGROUND IUSM is the only medical school in the state. In order to serve the entire state, the school has eight regional campuses across the state, in addition to the main campus in Indianapolis. First- and secondyear medical students attending IUSM are located at these nine campuses and receive varying methods of instruction, including didactic lecture, problem-based learning, and team-based learning. In addition, the IUSM curriculum is a competency-based curriculum, with students having to achieve certain levels within each of the nine competencies—Effective Communication; Basic Clinical Skills; Using Science to Guide Diagnosis, Management, Therapeutics, and Prevention; Lifelong Learning; Self-Awareness, SelfCare, and Personal Growth; Moral Reasoning and Ethical Judgment; Problem Solving; Professionalism and Role Recognition; Social and Community Contexts of Health Care—to successfully matriculate. Each IUSM campus (see Figure 1) possesses its own unique characteristics and strengths, as well as unique ties with each location’s host university and community. The Ruth Lilly Medical Library (RLML) in Indianapolis is the home library with extensive resources for the medical students all across the state. To support the lifelong learning competency in the first year, the librarians at RLML meet with the first-year students during their first semester to introduce them to e- 2 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go resources that are best for different types of background questions. Background questions are often generated from case studies and focus on definitions and general knowledge to fill one’s basic level of knowledge. During their first two years in medical school, students complete their basic science classes, regardless of their campus. They are in the process of building their knowledge base before moving into the third and fourth years, typically more focused on clinical experience. METHODS First-year medical students need a baseline understanding of the resources available and which resources are best for certain types of background questions. The authors had one hour with the students to cover the material and provide them time to work in groups. The training sessions began with an explanation of background questions and the importance of these background questions when building a knowledge base. The authors highlighted 11 types of background questions they may encounter during their first two years of medical school (see Table 1). A presentation of available eresources that would provide information for these types of background questions followed, complete with screenshots and highlights of some unique features for each e-resource. The students were then presented a case study (see Appendix) with specific questions to answer, utilizing e-resources presented to them earlier in the session. Students were divided into groups; each group was assigned a question and searched the various resources highlighted, and then shared which resources worked best for their type of question. Students found these highlighted e-resources via a Web site <http://library.medicine.iu.edu/body.cfm?id=39> designed specifically for them by RLML librarians; this specialized Web site listed the highlighted resources with a brief annotation for later reference and clarification. Each group informally shared findings with the class for its particular question; the students shared their specific question, the type of question (background information), and the resource(s) they thought were most appropriate, easy to use, answered the question the best, and so forth. Librarians 3 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go were able to provide the high quality and useful resources for the students, and the students, in turn, shared their findings with their peers and learned from each other. Students were directed to a summary Web page<http://library.medicine.iu.edu/body.cfm?id=247> created by RLML librarians that categorized the relevant e-resources for the different types of background questions. This page reinforces what the students discovered during their exploration and is intended to be used as a reference for the students throughout medical school. DISCUSSION The educational emphasis was on the process of identifying the types of background information, not the specific answer to a question. Medical students will encounter many questions throughout their medical career, and the questions will certainly be more varied than the 11 presented to them in this instance. Medical students need to be equipped with skills to generalize their question to a type of question, know where to look for answers, and be able to use this basic information-seekingmethod to find answers to the kinds of background questions they will encounter early in their medical school careers. Being able to apply information-seeking skills is also a component of the Lifelong Learning Competency, which addresses recognizing ‘‘personal limits in knowledge and experience and energetically pursuing information necessary to understand and solve diagnostic and therapeutic problems.’’1 RESULTS A short evaluation was distributed at four of the remote campus locations. From the student responses (n¼71), the following adjectives described the e-resources session: informative (89%), useful (82%), well-organized (79%), practical (69%), technology contributed to learning (62%), interesting (56%), and a 4 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go friendly, networking atmosphere (49%). Selected snippets from the students’ comments concerning the most helpful information they received included: Learning how to search using the different databases and what they were ‘‘good’’ for. Introduction to library resources—‘‘it’s what I’ve been looking for (and actually asked a professor about without results) for a while.’’ Doing the hands-on work on the computers. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY There are a plethora of e-resources available to the students that may answer background questions they will encounter throughout medical school. It would be impossible to highlight all of these resources in the time allotted and may only contribute to greater information overload. In addition, an hour limits the resources that can be introduced in a meaningful way. While students may Google and find something (or millions of hits), this educational program showed them resources specifically tailored for medical students (electronic textbooks, medical calculators, anatomy images, and normal laboratory values) during their first two years. CONCLUSION Informing medical students about e-resources available to them during their first semester of medical school gives them the tools to build their knowledge base. Teaching medical students which types of eresources are best suited for which type of question prepares them to successfully find information for the many questions they will encounter and teaches lifelong learning skills. 5 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go REFERENCE 1. IUSM Competency Curriculum. IV. Lifelong Learning. From ‘‘The Indiana Initiative: Physicians for the 21st Century.’’ (September 16, 1996). Available: <http://meded.iusm.iu.edu/Programs/Competencies/Compt4.htm>. Accessed: December 10, 2008. 6 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go ABOUT THE AUTHORS Elizabeth C. Whipple, MLS (ewhipple@iupui.edu) is Research Informationist/Assistant Librarian; Margaret (Peggy)W. Richwine, MS, MLS, AHIP (mrichwin@iupui.edu) is Director, Outreach Services; Kellie N. Kaneshiro, AMLS, AHIP (kkaneshi@iupui.edu) is Coordinator, Information Services Team; and Frances A. Brahmi, MA, MLS, PhD, AHIP (fbrahmi@iupui.edu) is Curriculum and Education Director; all at Indiana University School of Medicine, 975 West Walnut Street, IB 100, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5121. 7 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go TABLE 1 Type of Background Information Definition, basic facts Practice of medicine Disease – description, diagnosis, and treatment Drug – indications, interactions, etc. Differential diagnosis Diagnostic examination Laboratory test values Calculators Guidelines Images Review article 8 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go FIGURE 1 Indiana University School of Medicine Campuses. 9 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go APPENDIX—CASE STUDY Initial Clinic Visit: Subjective: Sr. Roberto Martinez is a 55 year old diabetic male, currently employed by a landscaping firm in Indianapolis, who presents with back pain. He came to the US from Mexico approximately 10 years ago on a seasonal agricultural worker (H2A) visa. For the first 5 years of his stay in the United States, Sr. Martinez worked as a farm laborer in rural northern Indiana. Four years ago, he was in an automobile accident and injured his back. At that time he underwent a 3-level lumbar fusion for an L-2 burst fracture, but the pain never completely resolved and is worse on some days than others. Sr. Martinez had been seeing his regular physician for this condition, but unfortunately the physician recently retired. He is coming to your clinic for an initial visit because he is out of the NSAID he takes for pain and because he has noted some new numbness on the outside of his left thigh for the past couple of weeks. Past medical history is significant for type II diabetes diagnosed 8 years ago which has been reasonably well-controlled with metformin. Social and family history: He currently drives a truck for a landscaping and yard care service. He has three children whom he still supports, and his mother and sister live in Mexico (part of his income goes to their support as well).His wife passed away last year due to complications of diabetes at age 52. In the past he had health insurance benefits through his wife’s work. His present job does not offer health insurance. Objective: GEN: Middle-aged Hispanic man with salt-and-pepper hair and sun-beaten skin resting comfortably on the exam table; somewhat anxious but in no acute distress. HEIGHT: 74 inches; WEIGHT: 311 pounds; BMI: 39.9 VITALS: BP:132=72 (large cuff) HR: 76=min RR: 28=min. T: 98.6 F oral. 10 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go MUSCULOSKELETAL: Lumbar spine has limited range of motion in all planes secondary to some muscle tightness and surgical fusion. Mild to moderate muscle spasm of the paraspinous muscles L>R but no trigger points. No bony tenderness. Moderate tenderness to palpation over the left sacroiliac joint with positive pelvic compression. Patrick and Gaenslen tests both positive. Straight leg raising reproduces pulling in the back on the left side but no radiation into the leg. Strength, sensation, and reflexes are normal in both lower extremities except for decreased sensation to light touch over the distribution of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve on the left. No thigh tenderness. Assessment and Plan: 1. Meralgia paresthetica, probably aggravated by tight belt and obesity. Numbness unlikely to be caused by lumbar disk disease or spinal nerve root impingement. Patient reassured that this will likely resolve with weight loss and the avoidance of constrictive garments and belts. May need dietary consultation if weight loss efforts fail. 2. Left sacroiliitis with paraspinal muscle spasm. Refill Naprosyn 375 mg BID for use on a regular schedule and begin Vicodin for breakthrough pain, particularly at night. Use heat and ice as symptomatically helpful. Will avoid muscle relaxants for now because of potential sedating effects. 3. Degenerative disease of the lumbar spine is most likely the cause of patient’s chronic pain. Will obtain plain X-rays today and consider MRI if symptoms worsen or become more suggestive of disk disease or spinal stenosis. Begin an exercise program and possibly physical therapy after the S-I joint inflammation subsides. Will also review the evidence for the use of glucosamine and chondroitin for osteoarthritis prior to next visit. 4. Type II diabetes mellitus, uncertain control. Obtain hemoglobin A1C. 11 Teaching First-year Medical Students Where to Go Schedule follow-up appointment in 4 to 6 weeks. Questions regarding Sr. Martinez to research: 1. What is meralgia paresthetica and how is it treated? 2. What are paresthesias? What are other possible causes (i.e., the differential diagnosis)? 3. What is the Patrick test and what does a positive result mean? 4. What is hemoglobin A1C, and what is the normal reference range? 5. What are some adverse effects of metformin? Does it interact with Vicodin? 6. Given Sr. Martinez’ history of diabetes, how would you calculate his risk of stroke over the next 10 years? 7. Where can you find an image of the sensory distribution of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve? 8. Where can you find an easy-to-read authoritative Spanish language article on losing weight to give Sr. Martinez? 9. Where can you find local financial assistance programs that may be able to help Sr. Martinez? 10. Where can you find a review article that discusses the use of both glucosamine and chondroitin for osteoarthritis? 12