45 minute video / BUSTED: The Citizen's Guide to Surviving Police

advertisement

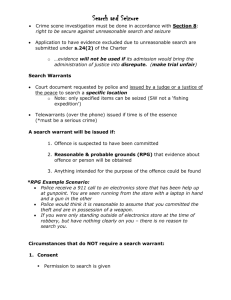

Explain the 2nd amendment (chapter 20) a. Militia i. The ability of the State to call upon its people to defend itself. Not a standing army but a called upon army/militia ii. NOT the National Guard In 1982 the Senate Judiciary Committee Sub-committee on the Constitution stated in Senate Document 2807: "That the National Guard is not the 'Militia' referred to in the Second Amendment is even clearer today. Congress had organized the National Guard under its power to 'raise and support armies' and not its power to 'Provide for organizing, arming and disciplining the militia.' The modern National Guard was specifically intended to avoid status as the constitutional militia, a distinction recognized by 10 U.S.C. 311(a). Title 32 U.S.C. in July 1918 completely altered the definition of the militia and its service, who controls it and what it is. The difference between the National Guard and Regular Army was swept away, and became a personnel pay folder classification only, thus nationalizing the entire National Guard into the Regular Standing Armies of the United States." The "militia" was provided for in Section 10 of the United States Code (often abbreviated USC). The Code is the list of all the laws that are written by the federal government. Section 10 USC 311 reads: "All able-bodied males at least 17 years of age…and under 45 years of age who are or have made a declaration to become a citizen of the United States." Additionally, another provision allows for a "reserve militia" (as opposed to the "ready militia" described above), that includes women, children and the elderly. b. Bear Arms i. United States v. Miller (1939) 1. Upheld National Firearms Act of 1934 a. Stated you could not transport sawed-off shotguns, machine guns, or silencers across State lines, unless the transporter got a license with the Treasury Department and paid the $200 license tax. b. Courts didn’t see the need of those weapons in “the preservation . . . of a wellregulated militia.” c. Miller never showed up to the Supreme Court hearing so he never presented his side ii. Brady Law The Brady law is a federal law (18 USC 922(t)) requiring instant background checks on prospective gun buyers. When a firearms dealer sells a handgun, shotgun, or long rifle to a prospective buyer, a background check must be performed on that person in order to ascertain whether or not that person is prohibited from owning a firearm due to past criminal actions. 2,356,376 background checks were performed the first year the Brady law took effect, at a cost of about $24 dollars per check. Of those checks, only four prosecutions were initiated. That's 14.1 million dollars per prosecution. Plus, local law enforcement agencies had to take officers off of the streets, and put them behind desks to process applications and perform background checks. Do you think this had any tangible effect on reducing crime? Brady Law: http://www.bradycampaign.org/ NRA: http://home.nra.org/#/nraorg iii. Nebraska Constitution Article I, Section 1 1. All persons are by nature free and independent, and have certain inherent and inalienable rights; among these are life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and the right to keep and bear arms for security or defense of self, family, home, and others, and for lawful common defense, hunting, recreational use, and all other lawful purposes, and such rights shall not be denied or infringed by the state or any subdivision thereof. To secure these rights, and the protection of property, governments are instituted among people, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. 2. http://www.handgunlaw.us/states/nebraska.pdf Code Section 28-1201, (Chapter 28 – 1200s) Illegal Arms Machine gun; short rifle or short shotgun; defaced firearm; stolen firearm Waiting Period None 1. Under 18: revolver, pistol, or any short-barreled hand firearm (without supervision); 2. Who May Not Own Convicted felon/fugitive from justice: barrel less than 18 inches Law Prohibiting Firearms On or Misdemeanor. 28-1204.04 Near School Grounds VIDEOS: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7RgLEGibyXs (22 minutes long – History Channel) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbq--pFYcLw (Ron Paul) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=joBMq6b4MmE&feature=related (Penn & Teller) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-6qLC7MkvA&feature=channel (GREAT AD!!!) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ExC7fE1LaY&NR=1 (911 Caller defends herself) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-MvfDW8MOk&feature=related (911 Caller again) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTuBsB_Q6oY&NR=1 (Man defends himself!!!!!) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lN7lBBbn9l4&feature=related (Ex-boxer defends) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHZNMR3k8XQ (Criminals for gun control) 2. Explain the 3rd amendment a. b. 3. Quartering of troops (illegal) We have Security of Home and Person Explain the 4th amendment (chapter 20) a. Define search warrant i. Court order authorizing a search b. Illegal Search and Seizure i. Define writs of assistance 1. Blanket search warrants used by the British /// ILLEGAL ii. Define probable cause Reasonable suspicion of a crime 1. Florida v. J.L. (2000) a. Miami Police got an anonymous tip about a teenager with a gun at a bus stop. They found, searched, and arrested the teen but did not have a warrant. b. Supreme Court found this unconstitutional (no warrant or probable cause) 2. Minnesota v. Carter (1999) a. Minnesota cop saw drug dealers bagging cocaine through a window. He arrested the dealers b. Legal because it was “in plain view” 3. Lidster v. Illinois (2004) a. Police set up a road block to gather information about a hit and run accident. Lidster was questioned and alcohol was found on his breath. He failed sobriety tests and was charged with drunk driving. b. Constitutional. Lawyers argued the police had no reason (probable cause) to question Lidster in the first place. He lost and then lost again. Sorry, just bad luck I guess. 4. Horton v. California (1990) a. Cops entered Horton’s house with a warrant to look for stolen jewelry. Found illegal weapons instead and arrested Horton. b. Constitutional because weapons were “in plain view” 5. California v. Greenwood (1988) a. Constitutional for cops to search your trash once it is set out. You give up your property rights at that point. You have no “reasonable expectation of privacy” b. DUMPSTER DIVING IS OK!!!!!!!!! 6. Florida v. Riley (1989) a. b. iii. Arrest 1. The Supreme Court in a 5-4 vote reversed the decision arguing that the accused did not have a reasonable expectation that the greenhouse was protected from observation from a helicopter, and decided that therefore the helicopter surveillance did not constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment. (Plain view) Arrest is the seizure of a person a. Minnesota v. Dickerson (1989) i. Facts of the Case: On November 9, 1989, while exiting an apartment building with a history of cocaine trafficking, Timothy Dickerson spotted police officers and turned to walk in the opposite direction. In response, the officers commanded Dickerson to stop and proceeded to frisk him. An officer discovered a lump in Dickerson's jacket pocket, and, upon further tactile investigation, formed the belief that it was cocaine. The officer reached into Dickerson's pocket and confirmed that the lump was in fact a small bag of cocaine. Consequently, Dickerson was charged with possession of a controlled substance. He requested that the cocaine be excluded from evidence, but the trial court denied his request and he was found guilty. Minnesota Court of Appeals reversed, and the State Supreme Court affirmed the appellate court's decision. ii. Question: When a police officer detects contraband through his or her sense of touch during a protective patdown search, does the Fourth Amendment permit its seizure and subsequent introduction into evidence? 1. Was the police officer who frisked Dickerson adhering to the Fourth Amendment when he formed the belief, through his sense of touch, that the lump in Dickerson's jacket pocket was cocaine? iii. Conclusion: Yes and No. In a unanimous opinion authored by Justice Byron R. White, the Court recalled that a police officer may seize contraband when it is in plain sight, and "its incriminating character is immediately apparent". It held that instances in which an officer uses the sense of sight to discover illegal goods are analogous (similar in nature) to those involving the sense of touch. The Court also reasoned that the tactile detection of contraband during a lawful pat-down search does not constitute any further invasion of privacy, therefore warrantless seizure was permissible. 1. The Court also concluded that the police officer frisking Dickerson stepped outside the boundaries outlined in Terry v. Ohio which requires a protective pat-down search to involve only what is necessary for the detection of weapons. In fact the officer was already aware that Dickerson's jacket pocket did not contain a weapon, when he detected the cocaine through further tactile investigation. 2. COCAINE WAS FOUND INADMISSABLE IN A COURT OF LAW b. Illinois v. Wardlow (2000) i. Police were patrolling an area of Chicago when Wardlow bolted for no reason. Police chased him down and found an illegal weapon on him. They arrested Wardlow. ii. Court found the arrest constitutional because Wardlow bolting was “common sense” grounds on which to believe he was involved in some criminal activity. iv. Define exclusionary rule Evidence obtained illegally cannot be used in court Police: To enforce the law you must obey the law. 1. Weeks v. United States (1914) Facts of the Case: Police entered the home of Fremont Weeks and seized papers which were used to convict him of transporting lottery tickets through the mail. This was done without a search warrant. Weeks took action against the police and petitioned for the return of his private possessions. Question: Did the search and seizure of Weeks' home violate the Fourth Amendment? Conclusion: In a unanimous decision, the Court held that the seizure of items from Weeks' residence directly violated his constitutional rights. The Court also held that the government's refusal to return Weeks' possessions violated the Fourth Amendment. To allow private documents to be seized and then held as evidence against citizens would have meant that the protection of the Fourth Amendment declaring the right to be secure against such searches and seizures would be of no value whatsoever. This was the first application of what eventually became known as the "exclusionary rule." – Federal Gov’t Only 2. Mapp v. Ohio (1961) a. Cleveland police entered Mapp’s home without a warrant looking for gambling evidence. They found nothing but did find obscene materials. He was arrested. b. Courts found this unconstitutional i. States cannot infringe on your rights either (14th) 3. Nix v. Williams (1984) a. CASE: 10-year old girl disappeared from a Des Moines YMCA. A witness reported having seen Robert Anthony Williams leaving the building carrying a “big bundle.” Police arrested him 2 days later. They were told not to “conduct any interrogation.” During interrogation, police convinced Williams to admit to the location of the body. b. “inevitable discovery” exception i. If the evidence would have turned up eventually then it is OK. c. Courts found this constitutional 4. United States v. Leon (1984) a. Federal agents entered home with a faulty search warrant for illicit drugs. b. Court upheld conviction because it said, “When an officer acting with objective good faith has obtained a search warrant . . . and acted within its scope . . . there is nothing to deter.” 5. Arizona v. Evans (1995) a. Police used an erroneous computer printout which showed Evans had outstanding warrants for his arrest. A search yielded illegal material. b. Constitutional because cops acted in “good faith” it was a faulty report from the clerk 6. Maryland v. Garrison (1987) Arrest after the seizure of drugs in a 3rd story apartment. The problem, the wrong apartment. b. Constitutional because there is a little leeway for “honest mistakes” 7. United States v. Johnson (1999) – “Knock and Talk” a. Police knock on the door in an attempt to persuade the occupants to give them permission to enter. If the consent is forthcoming, they enter and interview the occupants; if not, they try to see from their vantage point at the door whether drugs or drug paraphernalia are in plain view. b. CASE: 4 Policemen, dressed in plain clothing, entered an apartment building and “heard” one of the apartments was “busy.” They went to the door and before they had time to knock the door flew open. They quickly looked in and yelled police. People in the room scrambled and one of the policemen “claimed” to see somebody throw a crack pipe on the floor. A search of Johnson, which he protested, produced weapons and drugs. c. COURT: Police acted unconstitutionally because the court did not believe the crack pipe observation. And even so, it did not warrant probable cause to search Johnson. Anything obtained after that was excluded. v. Automobiles http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRcDsFZLIFc http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyokKFIecIo 1. Carroll v. United States (1925) a. Federal prohibition officers arranged an undercover buy of liquor from George Carroll, an illicit dealer under investigation, but the transaction was not completed. They later saw Carroll and one Kiro driving on the highway from Detroit to Grand Rapids, which they regularly patrolled. They gave chase, pulled them over, and searched the car, finding illegal liquor behind the rear seat. The National Prohibition Act provided that officers could make warrantless searches of vehicles, boats, or airplanes when they had reason to believe illegal liquor was being transported. b. Upheld the warrantless search of a car, noting that probable cause existed and the mobility of the automobile made it impracticable to get a search warrant. The decision rested on the distinction between stationary structures and movable objects/vehicles. Not only is an automobile movable while stationary structures are not, there is also less of an expectation of privacy in automobiles. c. Arresting officer better show probable cause 2. Schneckloth v. Bustamonte (1973) a. Arresting Officer James Rand made a traffic stop of a car with one burned out head light and a non-working license plate light. The car had six occupants. Only one, Joe Alcala who was not the driver, produced a drivers license and told Rand the car belonged to his brother. When asked by Rand if he could search the car, Alcala consented. The consent was described as congenial. In the back seat of the car, Officer Rand found three crumpled checks which had been stolen from a car wash. The driver, Robert Bustamonte was arrested and convicted of possessing a stolen check. Bustamonte challenged his arrest, arguing that while he had consented voluntarily, he had not been informed of his right not to consent to the search. b. In an opinion written by Justice Stewart, the Supreme Court ruled that consent to search is valid as long as it is voluntarily given. Stewart held that police may not use threats or coercion to obtain consent, but that they need not inform suspects of their right not to consent to a search. c. Justice Thurgood Marshall, in a dissenting opinion, wrote "In the final analysis, the Court now sanctions a game of blindman's buff, in which the police always have the upper hand, for the sake of nothing more than the convenience of the police." 3. Michigan v. Sitz (1990) a. Court held that police can stop automobiles at roadside checkpoints to examine drivers and passengers for signs of intoxication – even when they have no evidence to indicate that the occupants of a particular car have been drinking. 4. California v. Acevedo (1991) a. Overturned rulings that said police needed a warrant to search a glove compartment, a paper bag, a piece of luggage, or other “closed container” in an automobile. b. One clear cut rule now: i. Whenever police lawfully stop a car, they do not need a warrant to search anything in that vehicle that they have reason to believe holds evidence of a crime. ii. BUT, they must prove the “reason to believe holds evidence of a crime” 5. Florida v. Jimeno (1991) a. a. b. Question: Does a suspect's consent to a search of his vehicle extend to closed containers found inside? Conclusion: Yes. In a 7-to-2 decision, the Supreme Court held that the search did not violate the Fourth Amendment's prohibition of unreasonable searches. "The touchstone of the Fourth Amendment is reasonableness," wrote Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist in the majority opinion. "We think it was objectively reasonable for the police to conclude that the general consent to search respondent's car included consent to search containers within that car which might bear drugs. A reasonable person may be expected to know that narcotics are generally carried in some form of a container." 6. Wyoming v. Houghton (1999) a. Extended California v. Acevedo (1991) to include a passenger’s belongings 7. Illinois v. Caballes (2005) a. Police can use a drug dog to search (sniff) around the vehicle for narcotics 8. Maryland v. Pringle (2003) “Guilt by Association” a. PROBLEM: If police lawfully stop a car that has multiple occupants in it, and upon a search contraband is discovered in the back, can all occupants of the car be arrested, even though police have no reason to believe more than one person knew about the contraband and they have no idea which person it was? b. CASE: Police pulled over car in the middle of the night. A routine checked showed nothing so the officer asked to search the vehicle. Driver agreed, Pringle was the front seat passenger. The result? As the Court explained in its opinion: “The search yielded c. 9. $763 from the glove compartment and five plastic glassine baggies containing cocaine from behind the back-set armrest. When the officer began the search the armrest was in the upright position flat against the rear seat.” All 3 passengers denied knowing about the drugs. Pringle eventually confessed, saying the drugs were his and he was going to party to sell the drugs for money or sex. COURT: Police acted constitutionally because the drugs were accessible to all in the car and since nobody admitted to it, all 3 could have been arrested. Pennsylvania v. Mimms (1997) a. The Supreme Court held that police officers may order a driver out of a car after a lawful stop, even in the absence of reasonable suspicion that the driver may be armed. The distinguishing fact here is that the removal of the driver from the car permitted in Mimms was pursuant to a lawful stop. The minimal intrusion on the individual is justified by the special risks that accompany an officer approaching the vehicle of a potential traffic offender. 10. Arizona v. Gant (2008-09) a. Facts of the Case: Rodney Gant was apprehended by Arizona state police on an outstanding warrant for driving with a suspended license. After the officers handcuffed Gant and placed him in their squad car, they went on to search his vehicle, discovering a handgun and a plastic bag of cocaine. At trial, Gant asked the judge to suppress the evidence found in his vehicle because the search had been conducted without a warrant in violation of the Fourth Amendment's prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures. The judge declined Gant's request, stating that the search was a direct result of Gant's lawful arrest and therefore an exception to the general Fourth Amendment warrant requirement. The court convicted Gant on two counts of cocaine possession. i. The Arizona Court of Appeals reversed, holding the search unconstitutional, and the Arizona Supreme Court agreed. The Supreme Court stated that exceptions to the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement must be justified by concerns for officer safety or evidence preservation. Because Gant left his vehicle voluntarily, the court explained, the search was not directly linked to the arrest and therefore violated the Fourth Amendment. In seeking certiorari, Arizona Attorney General Terry Goddard argued that the Arizona Supreme Court's ruling conflicted with the Court's precedent, as well as precedents set forth in various federal and state courts. b. Question: Is a search conducted by police officers after handcuffing the defendant and securing the scene a violation of the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable searches and seizures? c. Conclusion: Yes, under the circumstances of this case. The Supreme Court held that police may search the vehicle of its recent occupant after his arrest only if it is reasonable to believe that the arrestee might access the vehicle at the time of the search or that the vehicle contains evidence of the offense of the arrest. With Justice John Paul Stevens writing for the majority and joined by Justices Antonin G. Scalia, David H. Souter, Clarence Thomas, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court reasoned that "warrantless searches are per se unreasonable" and subject only to a few, very narrow exceptions. Here, Mr. Gant was arrested for a suspended license and the narrow exceptions did not apply to his case. i. Justice Scalia wrote separately, concurring. Justice Samuel A. Alito dissented and was joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts, and Justices Anthony M. Kennedy and Stephen G. Breyer. He argued that the majority improperly overruled its precedent in New York v. Belton which held that "when a policeman has made a lawful arrest… he may, as a contemporaneous incident of that arrest, search the passenger compartment of that automobile." Justice Stephen G. Breyer also wrote a separate dissenting opinion, where he lamented that the court could not create a new governing rule. d. WEBSTER: Tow and take an inventory search of the car to get around it. BUT you have to be consistent on impounding vehicles. vi. Drug Testing Federal mandatory drug tests don’t need a warrant or even probable cause 1. National Treasury Employees Union v. Von Raab (1989) a. Drug enforcement officers of the U.S. Customs Service 2. Skinner v. Federal Railway Labor Executives Associaion (1989) a. Railroad workers 3. 4. Vernonia School District v. Acton (1995) a. Oregon school forced athletes to take drug tests b. Constitutional i. BUT IN WASHINGTON: The decision involved athletes who sued the Wahkiakum School District in 1999 after the district began requiring students to undergo urine tests if they wanted to participate in sports. If the tests indicated drug or alcohol use, the student was suspended from sports but wasn't reported to police. Board of Education of Pottowatomie Countie v. Earls (2002) a. Random drug tests for anybody in competitive extracurricular activities is constitutional Parents take issue with school drug test policy CHESTERFIELD, VA (WWBT) – In November 2010, after caught skipping school, a Monacan High School sophomore boy was told to take a drug test. His parents were called to campus and that day decided not to have their son drug tested. The sophomore was automatically suspended for two weeks. Chris and Rhea George say their son was punished for their decision and are now fighting Chesterfield County Public Schools drug testing policy. Chesterfield County Public School spokesman Shawn Smith says for 20 years, the school system has required students be drug tested if there's reasonable suspicion. It's student policy and at the start of each school year parents sign the policy, agreeing to the terms. In the paper trail that covered their kitchen table, the George's said there was no physical proof the sophomore boy was on drugs or took drugs the day before Thanksgiving break. That Tuesday, the George's said their son and six others skipped school and spent the day at a nearby playground. The couple said it's where a school police officer discovered the teens. "The officer, when they approached the kids, smelled marijuana smoke," said Rhea George. "And the officer that did pick them up said there was no evidence that he saw of any drug use," said husband Chris George. But the decades old Chesterfield school policy doesn't require physical evidence for a drug test. According to the Standards for Student Conduct, a drug test is required after "reasonable suspicion" like: "bloodshot eyes, staggering, odor, agitation, or excessive tardiness." Because of privacy issues, spokesman Shawn Smith said the school can't comment on the incident "even if the information provided to NBC12 is incomplete or inaccurate." At up to $45 a pop, over the last two years Chesterfield schools has tested 429 students, totaling up to $19,300 of your money. The school system couldn't tell us the results because it requires going into student records. "The school system wasn't interested in working with us. They just kept citing policy," said Rhea George. "The entire attitude was if we ask your child to take a drug test for any reason you have no right to ask us why," said Chris George. They signed off on the test, but didn't follow through when they found out they would not get the results. Their son was automatically suspended: two days for skipping school, 10 days for refusing the test. The family immediately researched their options and set up a meeting the following school day to appeal the decision. "At that time we were basically told that it would not be overturned and it could not be overturned because if he overturned it then no kid would ever agree to take a drug test," explained Chris George. The George's eventually paid for their son to be tested. The results were negative. His suspension was cut in half. But Rhea and Chris George want the punishment taken off his record and the policy re-evaluated. Henrico County Public Schools and Richmond Public Schools do not pay or require students to take a drug test. Each school system handles drug issues on a case-by-case basis and includes parents in determining the consequences. The Chesterfield school system says it continually evaluates all policies, but a spokesman could not tell NBC12 when or if the drug testing policy would be reviewed by the school board. vii. Schools 1. New Jersey v. T.L.O (1985) a. 2 14 yr. old girls got caught smoking in the bathroom. Teacher took them to the Assistant Principle’s office where one girl admitted to the crime and the other (T.L.O) denied smoking at all. Assistant Principle opened T.L.O.’s purse and found a pack of cigarettes and rolling papers. A further search yielded marijuana and other drug paraphernalia, a large quantity of money, a list of students that appeared to owe her money, and 2 letters that implicated her in dealing. Police and mother were called. T.L.O. admitted to selling drugs. b. the court agreed with the School that “a warrantless search by a school official does not violate the Fourth Amendment so long as the official "has reasonable grounds to believe that a student possesses evidence of illegal activity or activity that would interfere with school discipline and order." 2. Safford Unified School District v. Redding (2009) Facts of the Case: Savana Redding, an eighth grader at Safford Middle School, was strip-searched by school officials on the basis of a tip by another student that Ms. Redding might have ibuprofen on her person in violation of school policy. Ms. Redding subsequently filed suit against the school district and the school officials responsible for the search in the District Court for the District of Arizona. She alleged her Fourth Amendment right to be free of unreasonable search and seizure was violated. The district court granted the defendants' motion for summary judgment and dismissed the case. On the initial appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed. However, on rehearing before the entire court, the court of appeals held that Ms. Redding's Fourth Amendment right to be free of unreasonable search and seizure was violated. It reasoned that the strip search was not justified nor was the scope of intrusion reasonably related to the circumstances. Question: 1) Does the Fourth Amendment prohibit school officials from strip searching students suspected of possessing drugs in violation of school policy? 2) Are school officials individually liable for damages in a lawsuit filed under 42 U.S.C Section 1983? Conclusion: 1)Sometimes, fact dependent. 2) No. The Supreme Court held that Savanna's Fourth Amendment rights were violated when school officials searched her underwear for non-prescription painkillers. With David H. Souter writing for the majority and joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts, and Justices Antonin G. Scalia, Anthony M. Kennedy, Stephen G. Breyer, and Samuel A. Alito, and in part by Justices John Paul Stevens and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court reiterated that, based on a reasonable suspicion, search measures used by school officials to root out contraband must be "reasonably related to the objectives of the search and not excessively intrusive in light of the age and sex of the student and the nature of the infraction." Here, school officials did not have sufficient suspicion to warrant extending the search of Savanna to her underwear. The Court also held that the implicated school administrators were not personally liable because "clearly established law [did] not show that the search violated the Fourth Amendment." It reasoned that lower court decisions were disparate enough to have warranted doubt about the scope of a student's Fourth Amendment right. Justice Stevens wrote separately, concurring in part and dissenting in part, and was joined by Justice Ginsburg. He agreed that the strip search was unconstitutional, but disagreed that the school administrators retained immunity. He stated that "[i]t does not require a constitutional scholar to conclude that a nude search of a 13-year old child is an invasion of constitutional rights of some magnitude." Justice Ginsburg also wrote a separate concurring opinion, largely agreeing with Justice Stevens point of dissent. Justice Clarence Thomas concurred in the judgment in part and dissented in part. He agreed with the majority that the school administrators were qualifiedly immune to prosecution. However, he argued that the judiciary should not meddle with decisions school administrators make that are in the interest of keeping their schools safe. viii. Explain wiretapping & other technology things Wiretapping, electronic eavesdropping, videotaping, and other more sophisticated means of “bugging” are now used 1. Olmstead v. United States (1928) a. Federal agents tapped a Seattle bootlegger’s phone without a warrant b. Gathered information (evidence) for months c. Constitutional because cops tapped the phone lines outside of his residence and office 2. Katz v. United States (1967) a. A gambler was using a public phone booth to place illegal bets. Police tapped the phone booth without a warrant. b. Unconstitutional (overturned Olmstead v. United States) 3. United States v. Knotts (1983) a. Police attached a “beeper” or a tracking device in a container of chloroform and put it in the seller’s car. The buyer took the container of chloroform and brought it home. Police followed him and made the arrest based on evidence found at the residence. b. CONSTITUTIONAL: The defendant “had no reasonable expectation of privacy in his movements from one place to another” using the public roads. Since the device had been inserted before the drum came in the possession of the conspirators, no trespass to their effects had occurred when the device was installed. Police must enter immediately. If delay, they must get a warrant. 4. Kyllo v. United States (2001) a. Police used the Agema Thermovision 210 thermal imager to peak into a suspected drug dealer’s home. They searched for heat generated by lamps used for growing marijuana. b. As the Court observed: “The scan showed that the roof over the garage and side wall of [Kyllo's] house were relatively hot compared to the rest of the home and substantially warmer than neighboring homes in the triplex.” After obtaining a search warrant based, in part, on these heat measurements, supplemented by utility bills and some informant information, the agents found an indoor growing operation involving more than 100 plants. c. In rejecting the “mechanical interpretation” of the Fourth Amendment by permitting law enforcement to use advanced technology without a warrant unless there had been a physical invasion of one's home, the Court observed that such a diminishing of our expectations of privacy “would leave the homeowner at the mercy of advancing technology-including imaging technology that would discern all human activity in the home” without entering it. The Court observed that while the technique used in the Kyllo case was “relatively crude,” it also stressed that “the rule we adopt must take account of more sophisticated systems that are already in use or in development.” ix. Other Cases: 1. Skurtenis v. Jones (2000) – Strip Searches a. Sandy Skurstenis was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol. At the time of the arrest, the officers found a handgun in the floorboard of her car, for which she had an expired permit. Before placing her in a holding cell at the stationhouse, a female officer, pursuant to a policy mandating such searches of all inmates, took her aside and asked her to strip down and to squat and cough. After an overnight stay, the detainee was taken to the infirmary where a male nurse examined her cranial and pubic hair for lice. b. Constitutional 2. Ybarra v. Illinois (1979) – Guilt by Association a. Police had a warrant for a tavern and its owner. When police arrived they searched everybody in the tavern. Ybarra was a customer and had bags of heroin on him and was arrested. b. sUnconstitutional = Police did not have a warrant for Ybarra, just the tavern 3. Hester v. United States – Open Fields a. In a prosecution for concealing spirits, admission of testimony of revenue officers as to finding moonshine whiskey in a broken jug and other vessels near the house where the defendant resided and as to suspicious occurrences in that vicinity at the time of their visit, held not violative of the Fourth or Fifth Amendments, even though the witnesses held no warrant and were trespassers on the land, the matters attested being merely acts and disclosures of defendant and his associates outside the house. P. 265 U. S. 58. b. The protection accorded by the Fourth Amendment to the people in their "persons, houses, papers, and effects," does not extend to open fields 4. Griffin v. Wisconsin – Probation Individuals a. The warrantless search of petitioner's residence was "reasonable" within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment because it was conducted pursuant to a regulation that is itself a reasonable response to the "special needs" of a probation system. i. Supervision of probationers is a "special need" of the State that may justify departures from the usual warrant and probable cause requirements. Supervision is necessary to ensure that probation restrictions are in fact observed, that the probation serves as a genuine rehabilitation period, and that the community is not harmed by the probationer's being at large. ii. The search regulation is valid because the "special needs" of Wisconsin's probation system make the warrant requirement impracticable and justify replacement of the probable cause standard with the regulation's "reasonable grounds" standard. It is reasonable to dispense with the warrant requirement here, since such a requirement x. DNA- http://www.denverda.org/DNA/Surreptitious_Collection_and_Abandoned_DNA_Cases.htm 1. Commonwealth v. Rice (2004) 2. People v. Ayler (2003) 3. State v. Christian (2006) 4. State v. Athan (2007) 5. Commonwealth v. Cabral (2007) 6. People v. Laudenberg (2008) 7. Pharr v. Commonwealth (2007) 8. State v. Galloway and Hoesly (2005) xi. Other Cases: 1. http://www.flexyourrights.org/busted 2. Florida v. Bostick (1991) – Investigatory Stops and Detentions Facts of the Case: In Broward County, Florida, Sheriff's Department officers regularly boarded buses during stops to ask passenger for permission to search their luggage. Terrance Bostick, a passenger, was questioned by two officers who sought permission to search his belongings and advised him of his right to refuse. After obtaining Bostick's permission, the officers searched his bags, found cocaine, and arrested him on drug trafficking charges. Bostick filed a motion to suppress the evidence on the ground that it was illegally obtained, but the trial court denied the motion. Following an affirmance and certification from the Florida Court of Appeals, the State Supreme Court held that the bus searches were per se unconstitutional because police did not afford passengers the opportunity to "leave the bus" in order to avoid questioning. Florida appealed and the Supreme Court granted certiorari. Question: Is the acquisition of evidence during random bus searches, conducted pursuant to passengers' consent, a per se violation of the Fourth Amendment's protection against unconstitutional search and seizure? Conclusion: No. The Court, in a 6-to-3 decision, noted that when deciding if a search request is overly coercive, within a confined space such as a bus, one must not look at whether a party felt "free to leave," but whether a party felt free to decline or terminate the search encounter. The Court held that in the absence of intimidation or harassment, Bostick could have refused the search request. Moreover, the fact that he knew the search would produce contraband had no bearing on whether his consent was voluntarily obtained. The test of whether a "reasonable person" felt free to decline or terminate a search presupposes his or her innocence. 3. Terry v. Ohio (1968)- Stop and Frisk Rule Facts of the Case: Terry and two other men were observed by a plain clothes policeman in what the officer believed to be "casing a job, a stick-up." The officer stopped and frisked the three men, and found weapons on two of them. Terry was convicted of carrying a concealed weapon and sentenced to three years in jail. Question: Was the search and seizure of Terry and the other men in violation of the Fourth Amendment? Conclusion: In an 8-to-1 decision, the Court held that the search undertaken by the officer was reasonable under the Fourth Amendment and that the weapons seized could be introduced into evidence against Terry. Attempting to focus narrowly on the facts of this particular case, the Court found that the officer acted on more than a "hunch" and that "a reasonably prudent man would have been warranted in believing [Terry] was armed and thus presented a threat to the officer's safety while he was investigating his suspicious behavior." The Court found that the searches undertaken were limited in scope and designed to protect the officer's safety incident to the investigation. xii. Facebook 1. http://www.kjrh.com/dpp/news/local_news/facebook-helps-local-police-make-arrests 2. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/08/16/arrested-over-facebookpo_n_683160.html#s127052&title=undefined 3. http://www.naplesnews.com/news/2011/feb/03/facebook-bully-cyberstalking-arrest-student-death/ 4. http://abclocal.go.com/wls/story?section=news/local&id=5890815 5. http://www.opposingviews.com/i/facebook-chat-leads-to-arrests-in-new-jersey-school-threat 6. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2011/01/07/national/main7224468.shtml 45 minute video / BUSTED: The Citizen's Guide to Surviving Police Encounters http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yqMjMPlXzdA