Attachment - School of Psychiatry

advertisement

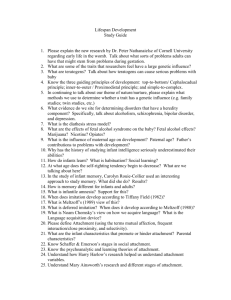

Attachment Dr Anne Shortall Learning outcomes • Increase knowledge of attachment theory • Describe healthy attachment patterns • Describe disorders of attachment • Diagnostic challenges • Assessment of attachment • Interventions • Relevance for adult mental health Why should adult psychiatrists care about attachment? • Understand underlying aetiological factors in adults who present with mental health disorders, particularly personality disorders • Understand how adults patients’ early attachment patterns could explain aspects of how that patient presents and uses services • Understand how patients with severe mental illness/ personality disorders’ parenting affects the development of secure attachment in their children and why that is important for the child. • Points towards where preventative interventions could be used in that group of patients. • Definitions of attachment • An affectionate bond between two people that endures through time and space and serves to join them emotionally • The deep and enduring connection established between child and caregiver in the first three years of life. It is a learned ability, the result of on-going two-way interactions characterised by protection, fulfilment of needs, limits, love and trust • Attachment is the base from which children explore, and their early attachment experiences form their concepts of self, others and the world • Through a positive two-way relationship children learn to regulate their mood and responses, soothe themselves and relate to others Definitions • Immediate and long-term benefits to mental health result if an infant or young child should experience a warm, intimate and continuous relationship between child and mother (or permanent mother substitute), in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment Purpose of attachment behaviours • It is through important attachment relationships that the child makes sense of herself, her emotions, other people and relationships • Early attachments affect the course of psychological and social development and mental health. For children who have not formed secure attachments during the prime ‘window of opportunity’ in the first three years of life, their chances of developing healthy attachment relationships in later life are diminished • Through repeated patterns of caretaker response, the child internalises a working model of his world and this guides his behaviour. Important attachment relationships help the child make sense of himself, his emotions, other people, and the social world Purpose of attachment behaviours • Attachment has survival value. It ensures physical survival and emotional well-being. It is behaviour concerned with response to stress and safety of the child • It is not the only domain of parenting- there are others e.g. discipline, play, etc. • Evolution has ensured that when infants experience distress, discomfort, anxiety or fear they seek closeness to an adult who provides protection, care and comfort. Closeness is achieved through attachment behaviors. E.g crying, signaling, holding up arms • How adults respond to the child’s discomfort and distress will affect how that child’s attachment style will develop, i.e. whether it will be healthy or unhealthy. Therefore parental sensitivity is important. Attachment behaviours • Babies are primed to develop attachments to caregivers • The existence of a relationship characterized by dependency is absolutely central. A child cannot ’learn’ about how to attach in the absence of a caregiver • How adults respond to the child’s discomfort and distress will affect how that child’s attachment will develop, i.e. whether it will be healthy or unhealthy • Internal working models established early in infancy are extremely robust • Attachment behaviour competes with exploratory behaviour. The less a child needs to engage in attachment behaviours, the more it will be free to explore, interact with and learn from it’s environment Attachment and exploratory systems • Are complimentary subsystems • Mutually inhibiting • The attachment subsystem is triggered by an internal anxiety thermometer • Once triggered all exploration is inhibited until security is found • The more the child can use their attachment figure as a ‘safe base’ the more time they can spend in ‘exploration mode’ • The exploratory system focuses attention outwards, motivating the child to explore and learn about the world Care giving styles • Sensitivity----------------insensitive • Acceptance-----------------Rejection • Co operation__________interference • Accessibility_____________Ignoring Care giving styles-examples from observation • Sensitive- parents meshes their responses to infant’s signals and communication to form a cyclical turn taking and pattern of interaction • Insensitive-Parent intervenes in an arbitrary way, these intrusions reflecting their own mood and wishes • Acceptance-parent generally accepts the responsibility of child care, demonstrating few examples of irritation with the child. • Rejection- Parent has feelings of anger and resentment that eclipse their affection for the child, often finding the child irritating and resorting to punitive control Care giving styles-examples from observation • Co operation-parent respects the child's autonomy and rarely exerts direct control • Interference- parent imposes their own wishes on the child with little concern for the child’s mood or current preoccupations • Accessibility-parent is familiar with their child's communication and notices them at some distance. Easily distracted by the child • Ignoring-parent is preoccupied with their own activities and thoughts They often fail to notice child’s communication unless they become very obvious through intensification Theoretical basis • 1)Attachment theory (Bowlby 1951,1969,1988) • Research and practice have confirmed its position as a most powerful and influential account of social and emotional development. • Bowlby asserted: • children are biologically prepared to contribute to attachment relationships, • a secure emotional base facilitates the development of self-esteem, empathy and independence, • attachment behaviours most obviously occur within the relationship between infants and parents between 6 months and 3 years. • ) Ainsworth et al (1978) 2 • Provided scientific support for Bowlby’s theory • Used the Strange Situation procedure to research child-parent interactions. • Identified three patterns of attachment: insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent and secure. Theoretical basis • Main and Solomon ( 1986 and 1990) • Used strange situation test to add further category- disorganized • Main and Goldwyn ( 1990) • Suggested that parents’ mental representations of their own childhood experiences determine their sensitivity to their child’s attachment needs and influence the quality of their parenting. • Developed the Adult Attachment Interview to assess an adult’s attachment experiences, the meaning to the adult of these experiences and their current internal working model. Strange situation test • Developed to assess attachment relationships between caregiver and child between 9 and 18 months • Developed by Mary Ainsworth • Child is observed playing for 20 minutes, during which time a sequence of events occur involving the carer and a stranger entering and leaving the room. The purpose is to raise the child’s stress and so observe the activation of their attachment behaviour. The amount of exploration- i.e. how much the child plays throughout is also observed Categories of attachment behaviour on SST • • • • • Ainsworth developed the following categories of attachment: Rates in non clinical populations Secure ( type B) -55-60% Insecure –avoidant- ( type A)-20% Insecure- ambivalent /anxious ( type C)- 10% • Disorganized – ( type D)- later added by Main and Solomon -up to 15% • These proportion are remarkable similar across cultures- secure is usually 55%-60% although rates of other types can vary slightly Behaviours in strange situation test • Secure pattern. • Child-uses care giver as a secure base to explore. May be distressed at separation. On carer’s return, greets caregiver positively, then gets on with exploring again • Care giver-sensitive to child signals. Responsive to child needs. Prompt response to distress Avoidant pattern Child explores with little reference to caregiver. May show little distress on separation . Avoids or ignores caregiver on return Carer-actively rejecting of attachment behaviour or insensitively intrusive. Lack of tenderness. Supressed parental anger Behaviours in strange situation test • Ambivalent • Child. Minimal exploration. Highly distressed by separation. Hard to settle on reunion , with mixture of clinging and anger • Caregiver. –minimal or inconsistent caregiving. Preoccupied responsiveness • Disorganized • Child . Lack of coherent pattern in exploratory or reunion behaviours. Can appear fearful or confused in caregivers presence e.g. rocking, covering face, sudden freezing • Carer-frightening or unpredictable. Insensitive to child’s cues, Can send child conflicting messages through body language. Secure attachment • Parent/Carer: available, protective, sensitive, responsive, accepting, consistent and predictable, able and willing to repair breaks in relationship. • Internal working model: I am lovable, effective, of interest to others; others are caring, protective, available, dependable. • As infant/young child: explores, experiments and learns through play; begins to understand own and others’ mental states. Secure attachment • As older child: has sense of self-efficacy, self confidence and social competence; able to draw on full range of cognitive and emotional material to make sense of the social world; good understanding of own and others’ feelings; appropriate trust in others and will approach for help; able to resolve conflicts; has some skills for coping effectively with frustration and stress. • As adult: values relationships; independent and secure. • As parent: consistent, responsive and predictable; able to promote secure attachment in own Insecure attachment-avoidant • Carer: consistently unresponsive to child’s needs and attachment behaviours; resentful and rejecting or intrusive and controlling. • Internal working model: I’m unlovable, of little worth; others are not available, are rejecting, hostile or interfering. • As infant/young child: deactivates attachment behaviours, appears detached; inhibits emotional expression; undemanding, self-sufficient; casually ignores parent; shows little distress on separation from parent; uncomfortable with closeness; exploratory behaviour outweighs attachment behaviour. Insecure attachment-avoidant • As older child: self-reliant, independent; achievement orientated (greater satisfaction obtained from exploration and activity than from relationships; cognitive ability may be good, however integration of thought and feeling is limited; distress is denied or not communicated; self-worth and selfconfidence is poor. • As adult: avoids emotional intimacy; intellectualizes emotions; task orientated; may appear cold and detached; views feelings as unreliable and insignificant and relies more on intellect. • As parent: child’s distress leads to anxiety; uncomfortable with caring role; dismissive of child’s distress and likely to view it as attention-seeking. Insecure attachment- ambivalent • Carer: inconsistent (sometimes available and responsive, sometimes not); unpredictable; insensitive and poor and interpreting child’s attachment signals. • Internal working model: I’m unlovable, of little worth and ineffective; others are unreliable, unpredictable, inconsistent and insensitive. • As infant/young child: amplifies attachment behaviours to ensure they are noticed; high but angry dependency (fretful, whingy, clingy); show marked distress on separation from carer but resist being soothed; attachment behaviour outweighs exploratory behaviour. Insecure attachment-ambivalent • As older child: pre-occupied with the availability of others; crave attention and approval, constantly strive to keep others engaged; escalate confrontation to hold attention of others; poor concentration skills, easily distracted; emotional states are obvious; sees things as all good or all bad. • As adult: pre-occupied with relationships but generally unhappy in them; jealous, possessive; ambivalent feelings not tolerated easily and dealt with by splitting (things, inc. people, seen as all good or all bad); feelings acted out, not thought through. • As parent: uncertain and ambivalent; needs child to have closeness and to feel accepted but insensitive to child; treats children as entirely wonderful or entirely awful. Disorganized attachment • Career: frightening to child (dangerous carer behavior e.g. through physical or sexual abuse or lack of self control due to substance misuse); frightened (alarming carer behaviour e.g. deeply unresponsive); following frightening behaviour, does not repair the relationship with the child. • Internal working model: I’m am unworthy of care; I am powerful but bad. • As infant/young child: Confused since wants to approach carer for care but is frightened of them and so wants to avoid them; fearful and helpless; distress and arousal remain high and unregulated; no behavioural strategy brings care and comfort. Disorganized attachment • As older child: fearful; and inattentive; highly controlling; avoids intimacy; relationships cause distress with little provocation; violent anger; often overwhelmed by strong feelings of being out of control, unprotected and abandoned and of being powerfully bad; cannot understand, distinguish or control emotions in self or others; dislikes being touched or held; apathy and despair co-exist with aggression and violence. • As adult: disturbance and disorganisation remains high. • As parent: very significant difficulty acknowledging and meeting needs of own children; look to children to meet some of their own needs. Other information about attachment • Attachment is person specific- child can have different attachment patterns to different care givers. • But during lifetime- these tend to become consolidated into one dominant pattern • We continue to develop attachment relationships during our lifetimeto partners, our own children Neurological basis • Brain develops in utero to a quarter adult size. Many brain cells unconnected. • Massive rate of development and growth over first 2 years. At 2 years, brain is 85% adult size and has twice the number of connections and twice the energy expenditure of the adult brain. • Brain cell connections established according to experience. The activity of brain cells alters the physical structure of the brain. ‘Those that fire, wire’. Experience and environment are the chief architects of the brain. Neurological basis • More connections established than needed. Connections that are seldom used or not well established are eventually pruned. • Parents play a vital role in establishing the neural circuitry that enables children to regulate their bodily functions and their management of their emotions. • Repeated neglect, adversity or abuse can result in underdevelopment of some areas of the brain and in over-sensitivity of others. It can also result in poor integration between brain areas. Neurological basis • The relevance to attachment is this: • Attachment style is robust since neural circuitry established early in life does not easily allow for the development of new skills of arousal reduction. • A child’s style of bodily and emotional regulation (which is controlled by it’s neural circuitry) typically elicits responses in other people which generally serve to reinforce the internal working model. (A child who has acquired good skills of self-soothing and impulse control will generally elicit positive responses from others, particularly adults. A child in whom such skills are lacking will often be seen as difficult and unrewarding and may elicit disapproval, distancing and possibly rejection from adults). What is disordered attachment? • Approximately 60% of children develop secure attachment. • Of the remainder many children will develop insecure patterns, i.e. avoidant or ambivalent. These patterns, whilst exhibiting some behaviours of concern, nevertheless represent an organised approach by the child to elicit care and to feel safe. It is important to remember that these patterns are not the same as disorders- they are v common in the general population. They may be risk factor but do not necessary lead on to mental health difficulties. • The term disordered attachment is probably most appropriately used to describe that proportion of children ( 5-7% of general population, 67% of children in foster care) whose attachment is disorganised and who show the greatest degree of disturbance. Here the child has been unable to identify a reliable way of orgainising behaviour that elicits care from carers and helps him to feel safe. Features of disordered attachment • Very common in looked after population • Dysregulation in number of domains of functioning e.g. • -Emotions-poor recognition of internal emotional states, labile mood, anxiety, angry outbursts; or very detached emotionally. • -Relationships- clinging; lack of discrimination; over friendly; or withdrawal. Poor maintenance of relationships. Need to be in control. Aggressive interactions. Ambivalence. Poor eye contact. Problems regulating physical closeness Features of disordered attachment • -Behaviour- inattentive, impulsive, poor concentration • - Cognitive- fail to learn from mistakes, poor cause and effect thinking, poor sequencing and planning – executive functioning problems • -Physical- enuresis, encopresis, difficulty sleeping, problems regulating food intake (too much or too little) • Many other symptoms can be attributed to disorders of attachment Disorganized attachment • Infants with disorganized attachment on the strange situation test are more likely to show high levels of aggression in middle childhood • This is likely to be a long lasting trait • Rates of disorganised attachment are much higher in children who are looked after; or where there is a history of abuse/ traumapossibly as high as 90% • There may be an overlap between the concept of disorganised attachment and the diagnostic category of Reactive Attachment Disorder. ( although some dispute that they are the same) Psychiatric definitions of attachment disorder • ICD 10- Reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited attachment disorder of childhood • DSM- Reactive attachment disorder- inhibited and disinhibited sub types • Initially described in institutionally reared children. • These are psychiatric categories and although they have some overlap with the concepts described above, there are some difficulties in their use. Reactive attachment disorders-ICD 10 • Onset before the age of 5 • Persistent abnormalities in the pattern of children’s social relationships- across different social relationships • Emotional disturbance ; reactions to changes in environmental circumstances. • Can have fearfulness and hypervigilance, poor social interaction with peers; aggression towards self and others • Occurs probably as a result of severe parental neglect, or abuse Disinhibited attachment disorder of childhood-ICD 10 • Pattern of abnormal social functioning that arises in first 5 years of lifetends to persist despite changes in environmental circumstances. Associated with severe early deprivation, absence of available caregiver and frequent change of caregiver. • Diffuse, non selective attachment focused behaviour; attention seeking and indiscriminately friendly; poorly modulated peer relationships • May have other emotional and behavioural disturbances • This pattern of indiscriminate socially disinhibited behaviour- appears to persist despite later developing secure attachment to care givers e.g. Romanian orphan study. Therefore- may reflect processes other than attachment. Problems with definition • Reactive attachment disorder-although clear types of behaviour exist, there are some problems in categorising this as a disorder of attachment • Includes cause as part of clinical definition • ICD10 /DSM definitions do not include anything about attachment behaviours in the clinical characteristics ( e.g. proximity seeking when distressed, acceptance of comfort) • Includes a lot of other behavioural descriptors e.g. challenging behaviour, cruelty to animals • It may be that the concept of RAD really reflects the broader consequences of early abuse/ trauma/ neglect. • Problems • • • • • • It is likely that RAD- includes symptoms such as impaired affect regulation; Heightened patterns of arousal; lack of reciprocity; lack of empathy Deprivation based behaviour e g. food hoarding Coercive controlling behaviour These can be seen as a result of a lack of early attunement and emotional regulation associated with neglect / abuse- probably modulated via changes in neural and endocrine systems • Is RAD- a disorder of social attuntement that follow on from early disorganized attachment pattern? Differential diagnosis • Children with attachment disorders are dysregulated in many ways- emotional dysregulation needs to distinguished from sustained depression, or Bipolar disorder in older adolescents • ASD- may be difficult to distinguish from disinhibited types of attachment behaviour-distinguishing features can include: • -specific communication deficits of ASD, e.g. echolalia, literal understanding, unusual voice tone not usually seen in attachment disorder. • -Play- in ASD tends to be related to intense interests, involve collecting/ordering; have high cognitive content. Children with attachment disorders may lack play skills but interests tend to be more usual. • -Social relationships-Children with ASD may show one sided interaction, unaware of other’s perspective. Children with attachment disorders- might lack social skills but do not have unusual types of interaction; can be highly attuned to other’s reactions. Differential diagnosis • Children with attachment disorders may have disregulated attention, poor concentration and hyperactivity- so will fulfil criteria for ADHD and may benefit from treatment for ADHD. But has to be seen as part of a broader pattern of difficulties Assessment in children • Focused observations of child and carer. Strange situation test- mainly a research tool. Adaptation have been developed for slightly older children • Structured assessment may be used, e.g. Story Stems, MCAST-play based methods designed to access attachment representations • Structured interviews for older children (7 upwards ) and adolescents.- e.g. adaptation of adult attachment interview. • Most of the above are predominately used in research; clinical assessment tends to rely on history taking and general observations Assessment in adults • Mainly structured interviews-self report questionnaires also exist • Most widely used- Adult attachment interview AAI- ( George, Kaplan and Main 1984) • Semi structured interview- lot of research validity • Aims to elicit adult representations of their attachment experiences. • Interview codes content and coherence of discourse • Categories are autonomous; dismissing; preoccupied; unresolved AAI categories • Autonomous-value attachment relationships, describe them in a balanced way. Discourse is coherent and internally consistent • Dismissing-have memory lapses. Minimize negative experiences, deny impact on relationships. Positive descriptions may be contradicted. • Preoccupied. Have continuing preoccupation with own parents Incoherent discourse. Have angry or ambivalent reprentations of the past • Unresolved- evidence of trauma or unresolved loss or abuse • Research has shown link between parents AAI categories- and later attachment of their infants on strange situation test Therapeutic interventions for children • A range of approaches have been developed. • None are, or attempt to be, a substitute for good quality care at home. They can only be an extra. • All professional attachment interventions emphasize the central importance of carers and largely describe therapeutic work with, and through parents, long-term substitute carers or adoptive families. Principles of care giving for children with disrupted attachments (Looked after children) • Information giving • Co regulation of emotions • Limit setting, discipline with empathy • Claiming behaviours • Help child build narrative about their experiences • Carer coping and self care Carer characteristics (looked after children) • Need for realistic expectations, flexibility in approach, persistence, stamina, and accepting long term nature of problems in some cases. • Maintaining calm reflective stance • Avoiding being drawn into negative cycle • Maintaining positivity • Managing extreme behaviours Therapeutic interventions • Therapeutic interventions aim to increase parental sensitivity to child's cues (behavioral interventions) • Combined in some cases with psychotherapeutic work with parents to work with their mental representations of their own childhood. • Number of video based feedback programs exist for parents and young babies e.g. infant parent programmes; watch, wait, wonder. • All other CAMHS interventions may be appropriate for managing the associated emotional and behavioral presentations Preventative interventions • Have been used in high risk groups with parents and babies • Or for adoptive parents and children • Tend to focus on behavioural change in parents- to increase parental sensitivity to infants’ cues • Many use video feedback techniques e.g. VIPP video feedback to promote positive parenting Therapeutic interventions • Parenting Education-understanding about effects of early disrupted attachment on current behavior • Adapted Webster Stratton groups ( parenting groups) • Attachment groups for carers • Parent-Child Game • Video interaction guidance • Relationship Play Therapy-theraplay, filial play therapy • Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy ( Dan Hughes) Evidence for interventions • Not a lot of clear evidence about therapeutic interventions. • Some evidence to suggest that behavioural based interventions can increase parental sensitivity especially with young children • But harder to address parents' own attachment representations • In older children, a range of CAMHS interventions may be useful for addressing problem areas such as increased arousal, social problem solving, coping with frustration, closer family relationships- but studies do not generally show a change in attachment status of the child • Studies favour- short term interventions with clear focus. Prognosis • In general, insecure attachment patterns are best thought of as risk/ vulnerability factors for later problems, including mental health disordersrather than predictive factors. • Little evidence about links between infant attachment patterns and later adult psychopathology. • Some studies have shown that those adults with preoccupied/ ambivalent attachment-have higher rates of mood disorder, anxiety and borderline personality disorder • Disorganized attachments in young children- are associated with later high levels of aggression in middle childhood/adolescence, and possibly predict a higher level of mental health difficulties in later life. Studies have shown link with more hostility in later adult relationships Prognosis • Difficult to know if continuity of problems is due to continuity of environment. • Psychiatric in patients- shown to have higher rates of disorganized attachment than controls • Extreme disturbances of attachment are like be associated with history of abuse and /or trauma as children as well • We do know that attachment patterns in parents- closely mirror those of their infants • Therefore consequences are broader than mental health difficulties but can affect quality of adult relationships, parenting, employment, criminality, drug use, etc.