SJC Class 2/3/2014

advertisement

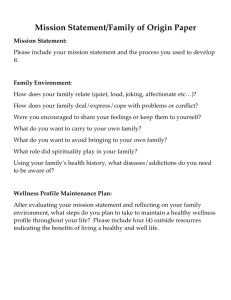

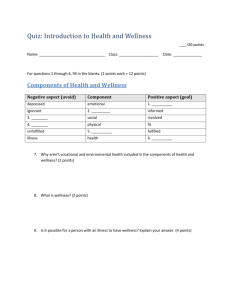

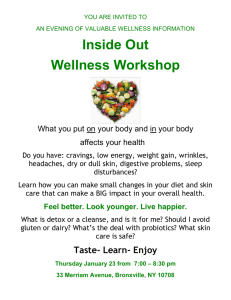

San Juan College Fit Together Casey Crotty INTRODUCTION TO WELLNESS FIRST, A QUESTION: What is health? Now… What is wellness? HEALTH DEFINED: “Health is optimal well-being that contributes to quality of life. It is more than freedom from disease and illness, though freedom from disease is important to good health. Optimal health includes high-level mental, social, emotional, spiritual, and physical wellness within the limits of one’s heredity and personal abilities.” - World Health Organization HEALTH VS. WELLNESS Although they are integrated and often used interchangeably, there is a difference between “health” and “wellness”: “Health” generally defines a presence or lack of disease, impairment, or other debilitating conditions. “Wellness” is the integration of interpersonal, emotional, spiritual, intellectual, environmental and physical components that expand the quality of life. Other considerations: Occupational wellness and financial wellness. A person with a physical illness or ailment but who possesses a good wellness has a better overall health status than one with no illness but poor wellness. HEALTH VS. WELLNESS Health – or some aspects of it – can be determined or influenced by aspects outside of your control such as genetics, age, and family history. Wellness is determined by lifestyle decisions: eating, exercising, intellectual and social stimuli; it is the conscious decision to control risk factors. SO WE COULD THINK WELLNESS LOOKS LIKE THIS: Physical Spiritual Social Emotional/ mental Intellectual BUT IN REALITY: BEHAVIORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO WELLNESS: Being physically active Healthy diet Maintain a healthy body weight Effective stress management Eliminate tobacco use Protection from disease or injury WELLNESS RELATED DIFFERENCES AMONG GROUPS: Gender: Differing incidences of diseases such as heart disease, cancers, and osteoporosis; differences in body composition and aspects of physical performance Race and ethnicity: Higher incidences of diabetes in Native American or Latino populations; higher incidences of hypertension in African Americans. Traditional diets and attitudes toward tobacco and alcohol also vary and have an effect. Income and education: Lower SES and lower education levels tend to have higher incidents of injury and disease, are more likely to smoke, and have less access to health care. Poverty and low education levels have far more important predictors of poor health than any racial or ethnic factor. “WELLNESS” IN MARKETING Media marketing (and even packaging) attempts to identify “wellness” with a product, service, or ingredient, even if benefits cannot be readily identified. Since “well being” is subjective, it’s easy to make claims for “improved wellness” without having anything to back them up. “Holistic” or “holistic health” is another term that consumers should be cautious about. As we look at nutrition, supplements, etc during this course, participants should develop a wary eye toward what they purchase. Persecution claims Claims of persecution by the medical establishment or claims that physicians “want to keep you ill so that you will continue to pay for office visits.” Too good to be true Enticingly simple answers to complex problems. Says what most people want to hear. Sounds magical. Suspicions about food supply Urges distrust of the current methods of medicine or suspicion of the regular food supply. Provides “alternatives” for sale under the guise of freedom of choice. Authority not cited Studies cited sound valid but are not referenced, so that it is impossible to check and see if they were conducted scientifically. Motive: personal gain Those making the claim stand to make a profit if it is believed. Testimonials Support and praise by people who “felt healed,” “were younger,” “lost weight,” and the like as a result of using the product or treatment. Advertisement Claims are made by an advertiser who is paid to promote sales of the product or procedure. (Look for the word “Advertisement,” in tiny print somewhere on the page.) Fake credentials Uses title “doctor,” “university,” or the like but has created or bought the title—it is not legitimate. Unpublished studies Scientific studies cited but not published anywhere and so cannot be critically examined. Logic without proof The claim seems to be based on sound reasoning but hasn’t been scientifically tested and shown to hold up. Latest innovation/Timetested Fake scientific jargon is meant to inspire awe. Fake “ancient remedies” are meant to inspire trust. Fig. C1.1, p. 24 EVALUATING SOURCES OF HEALTH INFORMATION Go to the original source Watch for misleading language Distinguish between individual research reports and public health advice Remember: anecdotes are not facts Be skeptical and use your common sense! EVALUATING SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON THE INTERNET: What is the source of information? Who is the author or sponsor of the site? How often is the site updated? What is the purpose of the page: promotion of products or procedures? Is there an obvious bias? Can you cross-reference other sources? Does the site conform to known guidelines or criteria for quality and accuracy? LET’S TALK ABOUT THE PROGRAM: This is an intensive program. You will need to: See your doctor at regular intervals through the course. Track your meals each day. Attend your fitness sessions. Be honest with yourself, with the Care Coordinator, and with your doctor. I encourage you to not think of this as a course or class. The process of achieving wellness is constant and dynamic, so I ask that you view this as an opportunity to change or enhance your life. HOW WE’RE GOING TO HELP YOU SUCCEED: We’ve put together several tools for you: The HRA (Health Risk Assessment) is a tool that you can use and refer to as often as you wish. The food tracking tools and reports are quite eyeopening! The IPA has opened a blog for you. Use it to yell out your successes, bemoan your setbacks, and for support (which goes both ways). OTHER LESSONS WE LEARNED FROM OUR INITIAL PROGRAM: Many of us don’t understand what “eating healthy” or “eating right” means. Many of us don’t understand what a fitness program will do physiologically. Very few of us have had the opportunity to connect nutrition, fitness, health risks, and our own personal health together in one place, at one time. TRANSTHEORETICAL MODEL FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE: Precontemplation: people do not think they have a problem and have no intention of changing behavior. Contemplation: people know they have a problem and intend to take action within 6 months. Preparation: people plan to take action within a month. Action: people outwardly modify their behavior and environment. Maintenance: successful behavior change for 6 months or longer. Termination: people are no longer tempted by the behavior which they have changed. GETTING STARTED… Examine your current health habits. Your HRA results will help you with this. Remember: be honest. Choose a target behavior. Pick one behavior to change Learn about that behavior Imagine yourself once the behavior has changed (self-efficacy). How is your target behavior affecting your level of wellness today? What diseases or conditions does this behavior place you at risk for? What are the risks and rewards of changing that behavior? Where is the locus of control: internal or external? Visualization and self-talk Role models and other supportive individuals Identify and overcome key barriers to change. …AND SETTING A PLAN: Write down your personal action plan Monitor your behavior and gather data (food logs, workout logs, HRA) Analyze the data and identify patterns (My Fitness Pal and HRA tools) Identify a strategy Get what you need: workout apparel, smart phone apps, etc. Modify your environment: remove snacks, soft drinks, etc. Control related habits: If you normally take a 15 minute break and have a soda, change to water, unsweetened tea, etc. Reward yourself! Involve people around you: tell your family, friends, co-workers. Plan for challenges: going out to dinner, birthdays, travel BE “SMART” ABOUT YOUR PLAN! Specific: state your objectives in specific terms: “I will exercise for 30 minutes, 3 times a week.” Measureable: Your goals will be easier to track if they’re quantifiable, so give your goal a number. Attainable: Set goals that are within your physical limits. If you haven’t run in some time, setting a goal for 5 mile runs each day may not be attainable. Realistic: Manage your expectations when you’re setting your goals. A 20-year smoker will likely not be able to quit cold-turkey! Time frame-specific: Give yourself a reasonable time to reach your goal, state the time frame in your behavior change plan, and set your agenda to meet that goal within the given time frame. FOR EXAMPLE: Week Days/week Activity Duration (mins) 1 3 Walk < 1 mile 10 – 15 2 3 Walk 1 mile 15 – 20 3 4 Walk 1 - 2 miles 20 – 25 4 4 Walk 2 – 3 miles 25 – 30 5-7 3-4 Walk/run 1 mile 15 – 20 21-24 4-5 Run 2 – 3 miles 25 – 30 FACING THE CHALLENGES AND STAYING WITH IT: When we say we “can’t” do something, it often boils down to we “won’t” or “don’t want to”. Progress-blocking sources to identify: Social influences Levels of motivation and commitment Choice of techniques and level of effort Stress barriers Procrastinating, Rationalizing, and Blaming DEALING WITH “LAPSES” People are seldom successful in the first attempt. Usually multiple attempts must be made to change one’s behavior. So you had a “lapse”? Forgive yourself. Give yourself credit for the progress you’ve made. MOVE ON. YOUR CHALLENGE: DON’T BREAK THE CHAIN The “Jerry Seinfeld” solution: http://money.msn.com/investing/post--no-jokehow-seinfeld-can-help-you-get-better-at-work (…or get better at being healthy!) REMINDERS: Next Class: Assessment lab! Measurements and photos Don’t even think about wearing big, baggy clothes! Friday: Fitness center orientation Check out: MyFitnessPal/SuperTracker sanjuanipa.com/wellness (and write a blog!) Must do’s: HRAs must be completed by 2/7 Doctor visits must be completed by 2/14